|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Herb WongState College, PA- "I can say that going to Korea was an experience. I felt proud that I had a part in defending my country against a dictatorship and helping to prevent communism from spreading. I had contributed." - Herb Wong

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

Memoir Contents:

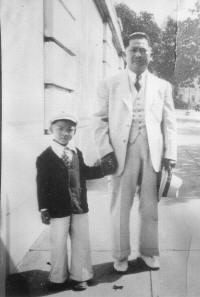

Pre-military

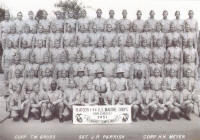

My name is Herbert Wong, but everyone calls me Herb. I was born on August 18, 1930 in West Allis, a suburb of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. I lived in West Allis during my early years (1930-1959). I was married in 1959 and moved to New York, where I got into the restaurant business working for my sister. In 1970 I moved my family to State College, Pennsylvania, where I currently reside, and opened the first Chinese restaurant here. My parents were George and Chan See Wong. They were both born in mainland China. Following their marriage in China, my parents immigrated to America in the late 1920s. My parents raised seven children. I have one brother and five sisters, three of whom were born in China. All who were born in China, including my parents, became naturalized U.S. citizens. In 1937 my father had a stroke. I was seven years old at the time. I don't remember much about it except that when I saw him in the hospital, he could not speak. He would write something on a piece of paper and we would read it. During his illness and eventually after his passing, my mother became the sole provider for our family. There were not a lot of children of Chinese-decent where I grew up in Wisconsin. Most were spread out throughout the area. I attended Roosevelt Grade School in West Allis before entering Holy Assumption Catholic school for a couple of years. I went to Horace Mann Junior High School before entering West Allis Central High School. At Central I played four years on the football team as a guard. During those years I was chosen Most Valuable Player and team captain. I was also on the All-Conference Team sponsored by the Milwaukee Journal. This team was selected by high school coaches throughout the Milwaukee area. I graduated from West Allis Central in 1949. Following graduation I began working in construction. I also signed up to play in the Wisconsin State Football League (a state amateur football program). I started for the Raatz Inn of Milwaukee. We were the undefeated state champions that year. World War II was coming to a conclusion when I entered high school. The war had considerable influence within my life. There were all kinds of war-support programs that I participated in. The school was very patriotic and attempted to contribute to the effort in many ways. Among the support efforts we participated in were scrap metal collection, buying war stamps and war bonds, and other things. When the war started, I was 11 years old. Even at that age I had a strong sense of patriotism. I always followed the war in the news. I listened to the radio all the time to hear what things were going on. I always wanted to be a member of the Armed Forces, but I was too young at that point to do anything. As a young kid I would read about all the heroic efforts that were happening during the war. I always wanted to be a Marine. I thought they were the most "gung ho" service. I was very proud of them. Since I was too young to join the military, I turned my attention to after-school jobs. I used to shovel snow. I worked in all different places. I was a workaholic. I did any kind of job I could get while I was in high school. I even worked at a soda factory two hours in the morning before I started classes. My job was to load and unload the trucks at Grafs Soda Plant in Milwaukee. I held a variety of jobs, mostly labor intensive. Throughout high school I worked on numerous construction jobs -- homes, buildings, offices, etc.. A friend's father was a builder, so I was able to work while getting on-the-job training. By the time I was 12 years old, I had steady work. I also worked on a Chinese farm, where we grew Chinese vegetables. We sold the vegetables in Chicago to the Chinese restaurants. For one of my jobs I worked in Chicago. When I was almost 12, I got a social security card by claiming I was sixteen. At that time you had to be that age to get one. That was 1942. One member of my family served during World War II. My older brother was old enough to serve early in the war, but delayed entry since he was studying engineering at Marquette University. Later, after changing majors, he became a dentist. Eventually he became an oral surgeon. My brother was a captain. He was in the Army ROTC program and after commissioning, was sent overseas during World War II. He served in China, Burma, and India. Joining the CorpsWith the Korean War underway, I enlisted in the Marine Corps on April 4, 1951 at our local Post Office in Milwaukee. I was a proud, and excited, 21-year old eager to serve my country. The Marine Corps sent me to San Diego for boot camp. The dividing line that determined whether a recruit would train at Marine Corps Depot Parris Island or San Diego was the Mississippi River. If you lived east of Mississippi you went to South Carolina. If you lived west, you went to California. Milwaukee was actually east of the Mississippi but Parris Island was so filled up with recruits at the time that they sent us west to San Diego. Because of the Chosin Reservoir campaign and the heavy loss of Marines, they started drafting Marines in addition to the traditional preference for volunteer enlistments. We traveled to California via troop train. As we went through the different states to San Diego, we picked up Marine recruits all along the way. I don't remember the precise route, but I remember that one of the first stops was in Chicago to pick up additional recruits. There were Pullman cars on the train, so we slept on the train. As we traveled, we got to meet more and more recruits from different parts of the country. It was very friendly along the way. We had good times in the dining car. Everyone played cards or talked, until we got to boot camp. Then everything changed abruptly! Boot camp is an experience I'll never forget. When we arrived at San Diego there were busses waiting for us, as well as the drill instructors (DIs). Immediately, they started screaming and yelling at us. We wondered what we had done. We got on the busses. The DIs were very strict and stern. I never saw them smile (even after graduation). You knew they meant business. As soon as we got off the busses, they rushed us around. They yelled at us every inch of the way. We felt like we were going into a prison or concentration camp. We were all lined up there. Then they took us into a building. We were more or less strip-searched to make sure we didn't have anything we weren't supposed to have. We were assigned a head drill instructor and two assistant instructors. My senior drill instructor was Sergeant J. R. Parrish. Corporal H. H. Meyer and Corporal T. W. Gruss were our junior drill instructors. I don't recall if they were World War II veterans, but they were very good and very sharp. Everybody in the platoon wanted to be just like them. They set a good example.

I tried to be as disciplined as I could during boot camp. But one of my main problems was that next to the recruit depot was the San Diego airport. I knew I was supposed to keep my eyes straight ahead, but every time an airplane flew over, my eyes automatically wandered up. The drill instructor knew recruits were doing that. So they'd come along and hit us on the head or helmet (or whatever we had on our head at the time) with their swagger sticks, to remind us that we were supposed to be at attention. There are other things I also recall. The DIs made you feel like everything you did was wrong. Everybody was required to work as a unit. So if one failed, everybody failed and all were punished. This motivated all members of the platoon to get it right. Of course the main purpose of this was to instill teamwork. If someone's bed wasn't made right, or if one person's shoes were not up to standards, we ALL got in trouble. We had two pairs of field shoes that were called boondockers. They laced differently. One had a straight lace on the front, and the other had a cross. We had to change shoes every day, rotating shoes with straight laces and crosses. A DI came along the line and right away he could see if someone had the wrong pair of shoes on. If someone did, that was punishable. Anybody caught smoking was also punished. We had to put a pail on top of our head and a cigarette in our mouth and then smoke it under the pail. Punishments also included running to a post and back -- running back and forth until you almost fell on your knees. The other thing the DIs used to make us do was duck walk. You'd have to get down on your haunches and put your hands behind your back and walk across the squad bay, and all over the place. I can't recall how long we had to do this, but it seemed like forever. And while we walked, we had to act like a duck and say, "Quack, quack, quack, quack!" If someone dropped his rifle, he had to sleep on it with the operating handle up. To lay across the rifle in this condition was very uncomfortable. At the time, I wondered if these kind of punishments were really necessary. Since then, I've come to realize that they did this for our benefit -- to make us realize that when an order was given it had to be obeyed. Otherwise, there would be a lack of discipline, and a lot of chaos. There were times when the DIs would say "Okay everybody, take a shower. You've got two minutes. Everyone rushed to follow orders. Invariably, many would find themselves to be a little wet behind the ears. That was punishable. If you brushed your teeth and didn't do it right, that was punishable. Everything we did was met with criticism. When we had a field day, we were expected to fully clean the squad bay. During the inspections the DIs would use white gloves to test for dirt. They examined every place and thing. The DIs always managed to find sand or dirt somewhere. The DIs would also take sand and throw it all over the barracks. We then had to clean it up in a certain amount of time. Sometimes we had to use our toothbrushes to clean because there was not supposed to be even a speck of sand. You could inspect just about anything and find sand, so it was no-win situation. Of course, that was punishable. We were always being punished. I guess that was part of the indoctrination process. We slept in bunks called double racks. We were given commands, by the numbers, to go to sleep. We stood alongside our rack. One stood in the front and one stood in the back. I recall that the recruit in the front was to lie down first and the one in the back next. Maybe it was the other way around! (Several years have passed, and memories fade.) On the DI's command everybody jumped in bed, sitting up at attention. Then he said "Two" and everybody was to lay down in unison. When he said "Three," everybody had to snore loudly. It didn't take long for us to actually fall asleep because we were so exhausted from the day. The next thing we knew the lights were back on in the barracks and the drill instructor was there with his swagger stick. He ran his swagger stick around inside a ribbed-metal garbage can. That's the worst sound you could hear in the morning. Everybody had to jump up and get things ready. We were now ready to face another day of intense scrutiny. We attended classes in the hot sun. Everyone was drained. We tried to retain whatever we were taught. It was very difficult, at times, trying to stay awake.

We were schooled in The General Orders -- what a guard's responsibilities were and how he should perform. You had to memorize the general orders, they tested you on it. They also taught us how to fire a rifle and pistol, as well as hand grenade throwing. Because a Marine is basically an infantryman, all Marines have to familiarize themselves with all kinds of basic weapons. The other branches of the service only know what they're supposed to do within their MOS. But in the Marine Corps, every Marine is a rifleman. There were several who did not make it out of boot camp. Some went to sick bay because they just couldn't take it. Some were given a "Section 8," which meant they visited the psycho ward because they broke down mentally. But that's what the DIs wanted to find out -- who could hack it. They did this in a training environment so we would not crack under fire. We would have to function as a team to survive in combat. There was no place in the Marine Corps for those who would crack under the strain of combat. The people who went to sick bay (not the psycho ward) who improved physically, were put in a delayed action platoon. Nobody wanted to go through another week or even another day of boot camp unnecessarily. Those who claimed they were sick or injured were most likely really incapacitated. When boot camp was finally completed there was a ceremony. Usually we wore our dungarees. On graduation day, however, we wore our service uniform. In this case, due to the time of year, it was our "Greens". If it was Summer, we wore our "Khakis". Now I understand that they have dress blue uniforms at graduation. But when I was in the Marine Corps, those were never issued to us. Once dressed, you went out onto the parade field and marched in front of the commanding general of the base. An honor platoon (the best platoon in boot camp) was picked. All of the officers were there. Parents and family members were allowed to come and watch their sons graduate. That was a very proud day for me. And it still is! My mother couldn't come because she lived in Wisconsin. It was too far and expensive for her to come, especially for just one day. But I had one months worth of leave on the books, so I went home. I was very proud of my status as a U.S. Marine. When I came home from boot camp, I felt like I was on top of the world. Leaving boot camp was synonymous to what it must feel like when you get out of prison. But I felt great because I knew that I had achieved something that was really hard to accomplish. Having played football in high school, I thought I was in real good shape physically. When I went into the Marine Corps, however, I found out what real physical fitness was all about. After my 30 days of leave were up I went back to Camp Pendleton for more extensive infantry training. This was called "ITR" (Infantry Training Regiment). In order to better prepare us for combat we received more testing on the rifle range, as well as on all the basic weapons the Marine Corps had. We were instructed in hand-to-hand combat, as well as bayonet training. We were taught that when you are in combat, and you are face-to-face with the enemy, you MUST keep in mind that its either you or the enemy. The training was so intense and pervasive, you did anything they commanded you to do. In other words, you listened, and obeyed, your orders like a good Marine. You didn't question orders. You were a member of a team and acted accordingly. The Chosin Reservoir campaign had recently ended and there was a push to get us to Korea as soon as possible. Unlike some Marines, who were fortunate enough to go to Bridgeport, California, we didn't receive any cold weather training prior to departure. Although it wasn't a surprise, we realized that we would be going aboard ship to either transit to Korea or participate in a Mediterranean cruise. The majority, of course, would go to Korea. Although I would have enjoyed an opportunity to see the Mediterranean, I knew my destiny was Korea. Shipping Out

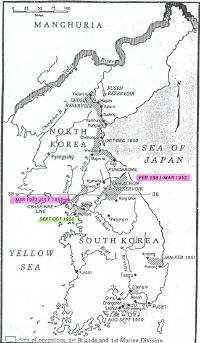

I left for Korea around mid-September on the Marine Lynx, a merchant ship. There were Marines assigned to the ship, as well as non-military employees. I don't recall if the employees were Merchant Marines or civilians. I had never been on a big ship before. I felt nauseous and sick to my stomach most of the trip, but I managed. I remember one friend of mine, Frank Chang, also a Chinese-American Marine, got so sick that they had to feed him intravenously. But he made it. I would run into Frank 46 years later at a 1st Marine Division reunion in Cincinnati. Frank ate some of the food that I brought him from the galley, but not much. Interestingly enough, the people who worked below deck were all Chinese. I knew how to speak Chinese fluently, so we got to be good friends. That’s also how I came to get extra chow! (I had learned Chinese after my father died. My mother never learned English. Back in those days, our parents wanted us to remain proficient in their native tongue. So we were only allowed to speak Chinese at home. Of course when I went outdoors, it was all right to speak English. Mother never did learn how to speak English. She was afraid that we might all start speaking English, and forget our roots. My own children don't know too much Chinese -- just a few words here and there.) Out of all the Marines and Navy personnel aboard ship, there were five Chinese-Americans and one Japanese-American. It took about 16 days to transit the Pacific. We arrived on either the first or second of October with the 13th Replacement Draft -- or "Lucky 13" as it was known. The first replacement draft to the Korean War was during August of 1950. I believe every month a different draft went through. I was replaced by the 25th replacement draft. Arriving in KoreaEn route to Korea, the ship docked in Kobe, Japan. At that point we transferred from the Marine Lynx to an APA Navy personnel carrier. The Navy took us from Japan to Korea. When we disembarked in Korea, there were Six-by trucks that took us to the front lines that night. We didn't even have a chance for a group briefing. We were loaded onto the trucks and shipped directly to the front lines. Welcome to Korea! At that time all Marines were located on the eastern peninsula of Korea. During March of 1952 we moved to the west coast.

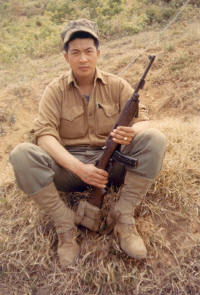

When we disembarked from the ship, it was already nighttime. This reminded me of World War II, from what I had read in the papers and heard on the radio. We had dimmed-out lights on the trucks, which meant there was only little slits over the headlights. One truck in our convoy drove off the mountain that night because the driver had no visibility. It was real late at night when the whole convoy stopped, due to the accident. We were not aware of what had happened at the time. Of course everyone was wondering what the hold up was all about. Word finally came back that the truck went off the road and that there were fatalities. Even though we were nervous about the road situation, the scariest part was that we had friendly artillery firing over our head. We couldn't tell the difference whether it was incoming or outgoing. When the artillery battery fired over our head, I thought we were being shelled. As a burst of artillery went over our head I thought we were going to die because there was a very loud BOOM directly over us. We soon learned the difference between incoming and outgoing artillery. Before long you became numb to it all. And being so tired we'd eventually fall asleep. Those of us who weren't officers did not know what was going on. In retrospect, I sometimes think maybe it was better we didn't know what was going on. We just followed orders. I was only a PFC then! The morning following our arrival to the front, we were greeted with the arrival of all kinds of wounded Marines. It was the first time I had seen anyone who had been shot to death. I looked at the corpse and wondered to myself "How did this Marine die?" I didn't see any blood. But when they lifted up his jacket I saw a little hole that had penetrated his chest. "So that's what the cause of his death was!" I thought to myself. When you look at something like that, it is hard to comprehend. This was the first time I was truly faced with the reality of war. It scared me. I thought to myself again "That could be me!" It dawned upon me at that moment that this was a real war and, like World War II, I could be here for the duration, which could be a couple of years. I would not be seeing my family soon. I was not even sure I'd ever be going home, except in a box. I decided to put those thoughts out of my head at that point. Assigned to H&SI was assigned to Headquarters and Service Company, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division. They were on the front line at that time. I was with S-2, which meant Marine Intelligence. Most of the time that I was in Korea, I was a scout and observer. I also had additional duties. My other Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) was 1441, which was map reading, overlays, intelligence data, etc.. My principal assignment, however, was always a scout and observer. I was to go on combat or recon patrols to obtain combat intelligence and/or capture the enemy soldiers. I spent a lot of time at our various outposts.

An outpost was a forward observation position (OP). While other troops stayed further back, those in a forward observing area moved closer to the enemy. There were only a few people who went to the OPs. OPs are like a finger that sticks out. It is the eyes and ears of the organization. In our particular OPs, we were in front of the mountain. We would radio back and report what we observed the enemy doing. Scouts would move forward from the OP to infiltrate enemy territory. In effect, we were modern day versions of the old wild west scouts of the American Calvary. I usually went by myself to an outpost. A lot of times the enemy had us zeroed in because they know we had only one route to get us there and back. I compare their tactics to hunters. They knew deer used certain paths, so they'd wait knowing we'd be coming through in one direction or another. But we took the chance anyway. Our tactic was to just pray and run like hell! We generally used nighttime for cover. Were those at an outpost easy targets? The answer is both yes and no. When we were there, the enemy could see us. But we could also see them. We had a few advantages also. We had observation planes. When we spotted the enemy, we'd call in air support. I'm thankful the enemy did not use their aircraft, especially when I was there. For the most part, the U.S. and its allies had air superiority, therefore it was almost impossible for the North Koreans and Chinese to deploy observation aircraft. We relied on our scout planes to check for enemy presence in the area. I saw American aircraft all the time. I watched what our air power could do to the enemy and it was devastating. Many times I watched strafing runs followed by a rocket attack. Then came napalm, which is a jellied gas. Napalm was particularly nasty. Once it got on human skin it just kept burning. There was no way to put it out. I tried not to get too close to others. It was hard losing friends. If you didn't have close friends, the pain of losing them in combat was less. Right? I recall some "short-timers" who were due to rotate out of Korea in a few short weeks. One night these Marines went out on a scouting patrol, only to be attacked and knifed to death. I was not that close to these Marines, but the loss was hard nevertheless. But there were those I did become good friends with. Marine Jerry Levenhagen was from my hometown. He played football and graduated the same year that I did. I remember him real well. Marine Richard Hertensteiner, a World War II veteran, taught me a lot of things about the Marine Corps. He was from Sheboygan, Wisconsin. He went overseas with me and ended up with my S-2 section. Both survived the war. I also remember Ron Ziolecki and Charlie Jump. I was close friends with both of them also. My commanding officer was Lieutenant Colonel Gerald T. Armitage. Officers and enlisted men don't mix company so it would be a stretch to say I knew him very well. But I did respect him very much. During the latter part of my duty in Korea, I worked in the colonel's office quite a bit. I did a lot of overlays for him and assisted in the planning. Following the war I tried to look him up, but was unsuccessful. Several years later, when I received a copy of a Marine Corps directory, I noticed Colonel Armitage's name and the fact that he was living in Naples, Florida. What a surprise that was! That was in 1998. Here it was, 47 years later! I gave the colonel a call and was surprised that he remembered me quite well. That made me feel good. I would like to go see him one of these days, but he is in his 80s now, and I'm no spring chicken myself. We had a nice talk on the telephone and have continued to keep in touch via the mail. The Marine Corps is such a small world. There is another officer, Colonel Gerald Russell, who served in Korea and now resides in my home town of State College, Pennsylvania. Colonel Armitage told me, interestingly enough, that Colonel Russell had command of the battalion that was supporting us when we made our last "push" in Korea. At Bunker Hill, we needed support and LtCol Russell sent reinforcements to help us out. Working with ANGLICODuring daylight, when I was at the outpost, I observed enemy movement, which I reported to a group called ANGLICO (Air Naval Gunfire Liaison Company). ANGLICO coordinated fire missions to inflict the greatest damage possible. ANGLICO's expertise enabled us to take the desired "high ground." This allowed us to maintain key observation posts that gave us the best positions to observe enemy activity.

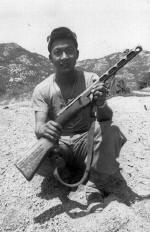

Additional DutiesMost of the other Chinese-American Marines in our unit served as riflemen. None stayed with me in the 1st Marines. Some went to the 5th Marines. Others went to the 7th Marines. I believe they made me a scout and observer because of my ability to speak Chinese. The Communist Chinese were now engaged in the war with their comrades, Communist North Korea. Although I was an interpreter, I required a Korean interpreter to help me sort through the language barriers that still existed. The Korean language is different from Chinese. Chinese is a difficult language. In northern parts of China, they speak very differently than those living in the south. Not only are the dialects in the north and south different, there are distinct dialects from village to village. It takes awhile and a lot of "What?" questions to finally realize what someone with another dialect is saying. Taking PrisonersSometimes I accompanied Marine patrols that infiltrated enemy lines. I have a special citation and promotion that resulted from one of those combat patrols. Later, I was promoted to Sergeant. I had a meritorious promotion from the General because I led a patrol into enemy territory.

At the time I participated in this particular patrol, we needed prisoners for interrogation. Prisoners were at a premium. Since we could not readily find them within our zone of action, we were sent out into bad guy territory to capture them. I managed to catch two prisoners on that patrol and brought them back. Major General Seldon was the Commanding General of the 1st Marine Division at that time. My meritorious promotion to sergeant was signed by him personally. The prisoners I brought back were North Korean. But even if they had been Chinese (the country of my parent's origin), I would have had no reservations with that. In the remote chance I'd have known one of the Chinese combatants, it might have been hard to fight him. But the fact was I didn't. If I was made aware that I had a distant cousin in the opposing enemy unit it would have been tough dealing with that mentally, But this was Korea and this was war. It was a matter of survival. Fortunately, this was not an issue. I was an American, first, foremost, and always! The fact that I was of Chinese descent did not cause me any problems relative to when I was out on patrol and returning to friendly lines. We had passwords to identify us. It was usually dark so it was hard to see well. During winter we wore white uniforms. The only part of our bodies that showed when we had the hood on was our face. Because of that, I always called in to let the others know we were coming back. One time when we were returning from patrol, we were told not to come in yet. There were infiltrators ahead of us. We ended up giving chase to these infiltrators who were now "trapped" The infiltrators we caught were really scared when we got hold of them. These infiltrators were coming into our lines to drop off "safe conduct passes" to us. We also dropped off "safe conduct passes" to them, but we always did so by air. The passes explained why we were fighting. Our passes gave them room to write a letter to their family. Always a Rifleman

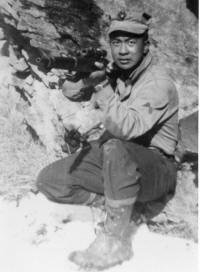

In my assignment, most of the time, I carried a .45 caliber pistol. I also carried a carbine, which is a small lightweight rifle. This provided me the mobility I needed around. I seldom carried the M-1 Garand rifle because it was bulky and difficult to maneuver on patrols. I also carried a K-Bar fighting knife. I had a sniper rifle with a scope on it when I went to the outpost. One of my jobs as a scout was to snipe at the enemy. Among other weapons, I carried hand grenades also. They were different looking from enemy grenades. We had regular, serrated grenades. The enemy had long strange-looking ones. I remember too well what they were like, but I seem to recall that they were like German World War II grenades -- canister-like devices. We also had concussion, white phosphorus ("Willie Peter"), and smoke grenades. The enemy had similar variations, but they were generally inferior to ours. My job in Marine intelligence could possibly be compared to work done by the FBI. We were there to find out how strong enemy troop concentrations were, what they were wearing, where their clothing came from (i.e. Russian or Chinese). I observed some enemy combatants who were wearing American items. Some had American cigarettes, American script, American pens, etc. That meant that they must have looted American war dead bodies or confiscated the items off prisoners. We sent this kind of information back to our S-2. At the division level it was the G-2. They assembled all the information we provided them. From there, they attempted to figure out how strong the enemy was, what units were fighting us, and things like that. I also occasionally found drugs on them. The enemy had a lot of quilted clothing. For shoes they had tennis shoes or what we call sneakers. They wrapped strips of cloth around their feet so many times. At that time, Marines wore leggings. You don't see leggings anymore. They have been outdated for a long time now. The enemy wore heavy, quilted material around their legs (bands of cloth wrapped around their legs--like soldiers did during World War I). Weather ConditionsI grew up in Wisconsin, which is known for being bitterly cold in the winter. But the weather in Korea was even colder and more nasty. I think that was because it was so damp and because the wind came gusting in through the hills from Manchuria. (Wisconsin doesn't have the hills.)

During the winter, we stayed in fighting positions on the reverse slope of hills. When we wanted to see what was going on, we would creep up to the top of the hill and make our observations. We didn't want to be on the forward slope of the hill since that would have made us easy and predictable targets. I often had to go down the back side of the observation hills we were on to get water. By the time I returned, the water was partially frozen in my canteen. Any water that had splashed on my body while collecting the water was frozen to my uniform. That's how cold it was. The winds were intense and blustery. As a result, everything froze quickly. The weather was awful and made combat even more miserable than it already was. The cold temperatures affected our weapons, especially if any moisture got into the operating parts. The gunfire mechanism would freeze up causing malfunctions. That never happened to me since I always tried to keep my weapon close to my body so that it would be relatively warm and dry. Taking a Hazardous TumbleI remember that when I first arrived in Korea, I didn't even know where the front line was. Shortly after arriving on the front our Marines caught two large Korean prisoners. They must have come from the north. It seems that in every country, the natives in the north are always bigger than those in the south. They wanted me to be a prisoner chaser that day. In other words, I was like a deputy sheriff, taking them back to our secured rear area. These particular prisoners I was escorting were walking in front of me. We made this particular sojourn at night. I had my trusty .45 drawn as we walked along a ridge line in pitch black darkness. It was the first time I had to draw a weapon for real. (I had never even hunted in the States!) But here I was, a "raw" boot escorting enemy combatants through the dark with a .45 drawn to protect myself. If the prisoners did anything I was expected to shoot them! As we walked back to the rear, I could barely see my prisoners. Here I was, an average size Chinese-American bringing back two large Koreans. The Marines in my unit couldn't tell if I was friend or foe. I kept yelling my password all the time. I spoke English out loud, even though it was just to myself. I wanted to make sure everyone in the rear knew which side I was on. Had a rear area guard seen us, I'm sure I might have been mistaken as an infiltrator and been accidentally shot. Being Chinese made me more cautious because I didn't want to be hit from both sides. During World War II, they didn't generally send anyone to the country of their origin to fight. For instance, the 442nd "Go For Broke" U.S. Army Division, which was composed of Nesi (Japanese American), were sent to fight the Germans, not the Japanese. They became one of the most decorated divisions in the Army during World War II. Almost everyone of Asian descent was sent to Europe to avoid any confusion on the front lines. But here, talk about confusion! During the night of my escort of the two Korean prisoners, visibility was very poor. We did not see a large bomb or artillery crater on our path. Next thing I knew we all stumbled and fell into the crater together. One prisoner fell below me, while the other fell on top of me. The prisoners could have killed me. I considered pulling the trigger of my .45, but there was no ensuing struggle. Everything happened very fast. I did not want to kill them, but I could have. Obviously they wanted to be taken as prisoners because they did not put up any fuss or fight. There was indeed a lot of confusion. They were yelling this and that, but I didn't understand Korean. They quickly got up and continued walking. I was very much in command. I yelled, "Get over there or Ill shoot you!" But I was just saying that for my own purpose. They couldn't understand what I was saying. I just wanted to yell loud and show them I meant business. That was my first face-to-face encounter with the enemy. It was up-close, personal, and VERY scary. As we got closer to our area, I kept yelling the password. I didn't really know where I was going except that I was heading in a steady direction. I finally got to the Military Police who were waiting. Everyday LifeMy brother was a dentist, so I acquired the habit of brushing my teeth every day, even on the front lines of Korea. In the wintertime, I used to take snow and ice and put it in my mouth to brush my teeth. Very seldom did we clean up. We would go for months without a bath. I've got pictures of my face with several days worth of dirt on it. You would think, from the picture, that I was a car mechanic. Although we were on the front lines, we still got our mail. That was our lifeline. My friends sent mail to me. My mother couldn't read or write in English, so my letters home to her were always interpreted through one of my sisters. I told my mother that I was in California and having a good time. I did not tell her that I was in a war zone. When I finally came back home, I did tell her, and she got mad at me. She said that she had a feeling something wasn't right because I never called her on the phone. My sisters knew. It occurred to me that if I had been killed in action, my mother would have been in a bigger state of shock since my letters indicated I was stateside. But I took my chances. I did not want her to worry about me. My mother was very attached to her family. My oldest sister is 20 years older than me. She is 89 years old, as of this interview date. Because of the age and roots difference, it is almost like there were two sets of families. My sisters would send "care packages" to me during my time in Korea. They would send dried food, candy, gum, nuts, certain baked cookies, etc. I never asked anyone to send me anything. But my sisters, friends, and neighbors took the time to show they cared, which I greatly appreciated. I wasn't looking forward to the food as much as I was the mail. Everybody was hungry for mail. Whenever the jeep pulled up and "mail call" was announced, everybody rushed down there to get their mail. Even today, nothing comforts a Marine like getting mail. We had a special delivery my first Thanksgiving in Korea. It came through the experimental use of helicopters. Hot chow was flown into the valley (reverse slope side of the mountain). The enemy could not see the helicopters coming. Chow Call was announced and everyone who could, ran down with their mess kits. We had hot turkey, mashed potatoes, and all the goodies. We knew Christmas was just around the corner. The only celebration on those special holidays was the special meals we received in the field. Our living quarters on the front line consisted of bunkers. When we returned to the rear, we stayed in tents. The tents had the ground dug out about four feet down inside. This provided protection from artillery, mortar, or hand grenade attacks. Digging had to be accomplished during the warmer months because in the winter, the ground became too hard to dig.

In Korea, most of the time was spent sitting around. Skirmishes with the enemy created intense moments, but there were times when we went for weeks without seeing any combat. When we had these lulls, we wondered what was going on? It seemed too good to be true. During those times, we joked around or played pranks on one another. Of course there were always card games to be found. Also, more patrols were sent out to get the most up to date intelligence data. We did see Korean civilians when we were going from the east coast to the west coast. We went through Seoul and saw that it was all bombed out. I saw a lot of Koreans there. Occasionally we saw civilians in the numerous rice paddies. Little children were carrying big loads on A-frames. The mamasans and papapsans were quite colorful and distinctive individuals. Once in awhile we had a chance to head back to the battalion rear area to see a USO show. I seem to recall the Four Larks were one of the shows I saw. I do remember that Betty Hutton was there (II took some nice photos of her). There was a sea of Marines on the hillside where all gathered to watch this particular show. From a distance the hillside-filled Marines looked like it was covered with ants. CombatWhenever the enemy wanted to find out anything about us, they generally did it through infiltration. We had native houseboys who took care of general cleaning and other chores. Many spoke English. These individuals ended up doing a lot interpreting. It was always possible that some of them could be enemy agents. Once, while serving as a scout, the enemy attacked our unit. I fought with our company, or wherever I was needed, because all Marines, as I have mentioned, are fundamentally infantrymen. We were put on a full front line alert. We knew the enemy was coming and waited. And we waited!!! Before long it got dark. It was very early the following morning when the enemy was spotted advancing towards us. The word was passed and we were ready. We were tired and nervous. Marines already baptized in combat get butterflies when they prepare for a fight. This was no exception. The tension of imminent combat amplifies the senses, especially hearing. Every noise we heard heightened our sense of pending danger. We let the enemy close in on us until we felt they were close enough (my adrenaline was really pumping now). We fired artillery flares, lighting up the area. We could now see the enemy. They were all over the place. We opened fire, unleashing a wall of bullets. The shooting was back and forth. We used our tracer rounds to home in on the advancing enemy. The enemy fought quite differently than we did. They like to use diversionary tactics. We were facing three enemy fronts when they attacked us. One unit was blowing bugles to one of our flanks. Another one engaged us with direct fire. Still another was creeping up on us from another direction. All of sudden, the shooting stopped. It became very quiet. Suddenly, the creeping unit opened fire. Slowly they moved towards us, trying to confuse us. They alternated deploying patterns. They were also yelling and screaming at us to invoke fear. They had hand grenades, guns, mortars, artillery, rockets, and rifle rounds. Finally they all came at once. And they did not stop. They came into our trenches, fox holes, and bunkers. Hand-to-hand fighting ensued. Grenades were tossed back and forth like hot potatoes! We were positioned in our bunkers and foxholes. As the flares continued to illuminate the battle site, all kinds of things were going through our minds. We knew that we were the best fighting force in the world. We were confident in everything we did. We also depended upon each other. We never leave our wounded or dead behind. I was afraid, but I knew my fellow Marines were counting on me, just as I was counting on them. We had a cause against fanatical communism, but we also had an even more solidifying cause -- each other! There were many times during this engagement when I thought to myself that this was the end. Prior to many of these engagements we would ask to have a chaplain come over. As soon we saw one, everybody would run over and kneeled down to say prayers. All denominations -- Protestants, Catholics and Jews participated. It didn't matter which faith. We all just gravitated to the chaplain. Our chaplain was stationed with us, as were our doctors and corpsmen -- all Navy personnel by the way. In the face of approaching combat we thought about all kinds of things. "What the hell did I get myself into?" or "Why did I ever join?" We'd think, "I could be home in bed or having a beer and a good time!" These thoughts came and passed quickly. When I was on the front line and saw the enemy advancing towards us, I'd wish myself good luck. Simple as that! When it seems like it is the end of the world, all kinds of things flash through your mind. But once the attack started, I just started shooting and the butterflies would disappear. The enemy was a mixture of both young and middle-aged. I never saw any older people. I wouldn't say these were good fighters. I don't think they had much experience. At one time I observed a lot of them surrendering. They came in hordes. They put up a white flag and came into our lines. As quick as an attack would start, it would also finish that way -- quickly. I remember once when I was on a hill, a brand new second lieutenant came up. He had nice, starched dungarees. He was a mortar officer in a weapons company. He called in fire and somehow got messed up with the coordinates. He called the fire in on himself, due to a mistake in his calculations. The next thing I knew they were carrying him off the hill. Training only provided us the basics for surviving in combat. It helped us cope. It was the actual experience of combat that counted the most. We all learned by experience -- some the hard way. We learned how to distinguish between incoming and outgoing artillery. If you were lucky, the older and more experienced Marines helped you learn the ins and outs of the front lines. The rest of us learned by experience. I don't recall serving with any notable heroes in Korea. I think most of us thought teamwork was the biggest hero over there. When everyone did their job, we survived. When they didn't, some would die. In Personal Danger

I stayed in Korea for twelve months. During that time there were three occasions when I felt I was in imminent, personal danger. We had three major campaigns for which we received battle stars. One was the UN summer/fall offensive. The next was the second Korean winter campaign. The third was the Korean summer/fall defense of 1952. During one battle, I was shot and wounded by a sniper. That happened on January 28, 1952. I was on Bunker Hill in August of 1952. The fighting there was quite heavy and we had many casualties. I lost many friends. After the engagement was over there were bodies laying all over the mountain side -- Americans, North and South Korean, as well as Chinese. Fortunately, most of the dead lying there were North Koreans and Communist Chinese. The graves registration folks took care of our dead. But the bodies of the enemy just laid there. No one came to retrieve them. After a couple of days, the bodies started smelling. That whole hill stunk. It was so bad you wanted to gag and vomit. You would lose your appetite. I left the area soon after so I never found out what happened with the bodies left behind. Going Home

When we found out we were going home, of course we were happy. We couldn't sleep at night, delirious with joy that we would be going home. We got a calendar and began counting our days. We marked each day off with enthusiasm. We were what they call "short-timers". A lot of the Marines were worn out by the intense war experience they had survived during their tour in Korea. But we each kept going. There was nothing you could really do about it. We wanted to serve with honor so we could return home to start our new life pursuits. That is when we all began to realize the value of the training we had received in boot camp. It taught us to be survivors. We worked as a group. Everybody did their part. If something happened to one person, everybody suffered. That's what they emphasized in boot camp. And that's what paid off for most of us in combat. I liked being in the Marines. And I was glad to go to Korea to serve my country. But I can’t say that I liked war, or being in a combat zone. I missed my family and my friends back home. For me, the hardest thing about being in Korea was the loneliness and the awful living conditions. There was also constant wondering about going home. It was not IF I'd come home, but in what CONDITION I would return.

When my time came to go home, I felt a sense of guilt. Even though I felt I had served my time honorably, I felt bad because others I had come to know had to stay. I don't know what happened to many of those friends I made in the Corps. That's just the fortunes of war I guess. When you get out of the military, you get busy with the rest of your life. And that is exactly what I did. After many years have passed, I guess the longing to revisit the past gets stronger. You take the time to start looking back on the journey you began so long ago. At the time, however, I just wanted to get back home. As part of the procedure for departing Korea, they took us to Ascom City. We were deloused there and had a chance to get clean clothes and a haircut. They checked us out physically to make sure we weren't carrying any parasites. From Ascom City, we departed Korea for Sasebo, Japan. We boarded a Navy troop transport. At Sasebo, we boarded another ship which sailed for the States. At last we were on our way home! When we first came to Korea aboard the Marine Lynx, you will recall I mentioned we stopped in Kobe, Japan to transfer to a Navy transport ship that would take us to Korea to join the war effort. We were given no time for any R&R in Japan. Those of us in the 13th Replacement Draft were needed immediately. On our journey home we thought we might finally get some R&R time in Japan. But that never happened. We never received liberty on the way over, or the way back. I guess that is why we were called "Lucky 13." We spent most of the time transiting the Pacific topside. When we hit bad weather, of course, we all went below. As we got closer and closer to the States, scuttlebutt (rumor) had it that we were only so many miles and days away. Of course the closer we got, the more anxious everybody became. When we finally sighted the Golden Gate Bridge, everybody came topside. As we sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge, tears seemed to be flowing down everyone's cheeks, including mine. There was a great sense of relief. We had made it! I couldn't believe I was home. How did we survive? Everybody bowed their heads and prayed as we entered port.

When we docked at San Francisco the Marine Corps band was there playing the Marines Hymn, and other selections. I was very proud. We disembarked and went to the local naval base. We had our first chow there since returning to the States. For some reason, everybody loved milk. That was something we missed quite a bit in Korea. The naval base chow hall had big vats of milk. Everybody went for the milk and, of course, all the fresh food. During our initial processing, we were given about a week of liberty in San Francisco. We did the town. I visited Top of the Mark, Fisherman's Wharf, and all the other prominent Frisco landmarks. Many of the guys got drunk. It was really something. Following processing, we got papers to go home before reporting to our new duty stations. After Korea I went to Camp Geiger, which was a force troop area at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. I served with the 2nd Amphibious Recon Company. We went out on rubber boats and camouflaged ourselves for infiltration training. We learned how to obtain intelligence, rescue hostages or downed pilots, and many other interesting things. I had the combat experience of Korea under my belt, but it was refreshing to note what good training I was receiving at Camp Geiger. This seemed kind of backwards to me, but the needs of the Marine Corps a year earlier set into motion my journey to Korea first. While at Camp Lejeune I served in Vieques, Puerto Rico. Mustering OutI was discharged on April 3, 1954. I had a desire to reenlist. I thought about it quite seriously. I loved the Corps, but I also loved my freedom. I decided freedom was more important at this point of my life. I almost joined the Reserves when I returned to Milwaukee. The closest Marine Reserve unit was either in Madison (an hour and a half away), or Great Lakes, Illinois. If it wasn't for the distance involved in drilling, I might have joined. As it was, I departed the Corps in good spirits, with a whole new life before me. During my service in the Marine Corps the medals and ribbons I received are Purple Heart Medal, Combat Action Ribbon, Presidential Unit Citation, Navy Unit Commendation, Good Conduct Medal, National Defense Medal, Korean Medal with three stars, Korean Presidential Unit Citation, United Nations Medal, and the Republic of Korea War Service Medal. Civilian Life

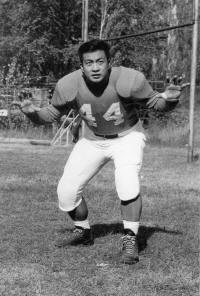

When I returned home I took advantage of the GI Bill. I received a Bachelor of Science degree from a small college in Waukesha, Wisconsin--Carroll College. I was accepted at Marquette University, but I had been out of school for such a long time that I decided to go to a smaller school instead. The GI Bill is probably what encouraged me the most to go to college. Upon entering college I was invited to play football because of my high school record. Having been absent from the game for four years, I was older than the majority of the other team members. I played the guard position on the team. I In some games I was selected as team captain of the Carroll College football team. There were other vets on the team also. We played in the Illinois Conference against schools like North Central, Milliken, Illinois Wesleyan, Wheaton, Lake Forest, Augustana, and Elmhurst. We also played St. Norberts in Wisconsin, Hope College in Michigan, and Wabash College in Indiana.

In 1958, there was a mild recession. Jobs were pretty hard to find at the time. Following graduation I met and married Theresa Lee. I used to go to Chinese student parties while I was in college. In fact, I was president of the Chinese student club in Milwaukee. It was a national thing. They had chapters throughout the United States. I met Theresa at the party and began dating her. We were married in early February of 1959. Nine and a half months later, our first child, Susan, was born. Two years later we had a boy, Herbert Jr. Two years after that our daughter Denise was born. And two years after that, we had another boy, David. David later went on to become a Marine. He went to Marquette University and got a Navy ROTC scholarship for all four years. He was a captain in the Marine Corps and served in the first Gulf War. He received the Navy Commendation Medal for calling accurate fire in on the enemy. I am very proud of him-- first, for being a Marine, and second for earning that medal. I'm proud of all my kids. I think they are terrific. As of 2002 I have nine grandchildren (five boys and four girls). After I got married, I didn't know what to do for a living. My brother-in-law said to come to New York and work with him for a while. I had four sisters in New York. All of them owned good-size restaurants. One restaurant was Gam Wah, which had 30 waiters in it. Our family had always been in the restaurant business. My Dad had a restaurant -- one of the first Chinese restaurants in Milwaukee. When he died, we lost all that. Some friends of ours had moved to State College, Pennsylvania. That was during 1970. They said it was a growing town and the people there needed more restaurants. The home of Penn State University, college students often stood in line till 2 a.m. in the morning to get something to eat. My friend said, "Why don't you come out here and open up a Chinese restaurant?" And we did. We opened the first Chinese restaurant in town. We called our restaurant "Suzie Wong's." We named it after our first daughter. Our children worked with us in the business. I'm retired now, but we still do catering of Chinese food. We are particularly known for our egg rolls. Son in the Gulf WarIt is not always easy being a Marine veteran, especially when you have to watch your own son go off to war. That is what happened, as I previously mentioned, with our own son David. I knew about combat, so I was very concerned when David left to participate in the first Gulf War. During Operation Desert Shield, David was stationed in Okinawa. We anticipated there was going to be a ground phase to the war and those units closest to the Gulf area would likely be called in first. That's when I started to get concerned, like any father would. My wife and I would stay up all night worrying about David. We couldn't sleep. We watched CNN all the time to find out what was going on. I became very religious at that point and began attending church every morning.

At first, I didn't know of David's whereabouts. But I knew he was there. At that time, you could call a toll-free overseas number. You could call up his outfit, give his name, and find out if he was okay. At every opportunity I called the number and asked about Lieutenant David Wong. They told me he was fine. That known, I could relax for that moment. Because I know how unpredictable combat can be, I remained very edgy. I would have gone over there in a heartbeat, but when it is you own child, it is different. David eventually came home safe and sound. We were very excited when he arrived. He flew into Camp Lejeune. We drove all night to North Carolina to see him and his fellow Marines, who marched onto a parade field for a review. I couldn't believe he was finally back in the States. It was very much a moment of pride for me. He had performed well. He is a perfectionist. Right now he works for Merck Pharmaceuticals, traveling all around the wonderful country he once helped defend. Final ReflectionsI was so busy after my discharge that I never had any dreams or nightmares about Korea. A lot of things were shut out because I've gone from one thing to another. I had to concentrate on my college studies and football, my family, my work. Everything about Korea was out of my mind for so many years. I didn't really remember too much about the experience. But one day, while looking through some old scrapbooks, following my retirement, I started wondering about whatever happened to this person and that person. The curiosity began channeling memories back that I had long forgotten. The questions asked in this interview [1999] have caused me to wonder, and remember, more. People haven't asked me a lot of questions about Korea, so I have to take the time to think back and reflect first. Certain things remain vague, but some things come charging clearly back into my mind. I regret that time has caused many friends to pass away since the war, and that I didn't have a chance to renew great friendships born of comradarie and shared experiences. My children are patriotic. I have told them about serving in the Korean War, but it didn't mean much to them. I didn't go into any details because I never felt they would be interested. I also didn't think sharing the horrors of war was necessary for them to hear. I tell them going to Korea was an eventful experience that I am proud to have participated in. I am honored that I was able to serve my country and help arrest the spread of communism. Going to Korea gave me a unique perspective on my own country. I appreciated the fact that we were concerned enough to send troops to Korea to fight communism. I have always felt we were doing the right thing. The fall of communism during the 1990s validates that feeling. I believe we won the war in Korea, despite the fact that many still refer to it as a stalemate. Today South Korea has a stable and dynamic country. It is a free and democratic republic, while the northern half of the peninsula remains under a brutal dictatorship. The Korean War was not a "Police Action." The Korean War was one of the worst wars in the 20th Century, as far as deaths casualties per year. U.S. worldwide casualty figures for the Korean War were 54,246 during 1950-1953. For the Vietnam War it was 58,135, between 1965-1973. World War I saw 116,708 die from 1917-1918. World War II figures list 407,316 from 1941-1945. The heaviest losses for the Marine Corps in Korea occurred during the Chosin Reservoir campaign. Marines who fought after Chosin also incurred heavy losses. High intensity battles like Bunker Hill should not be forgotten. All the various campaigns were part of something bigger. All Marines fought bravely. We fought, bled, and often died under grueling conditions. Once a Marine..."Once a Marine, Always a Marine" is very true. I can go up to just about any Marine and talk for hours. A Marine Corps general once told my wife that he missed many airline flights because when he started talking to Marine veterans he'd run into at airports, the next thing he knew, he had missed his plane. I started going to the 1st Marine Division reunions last year. I attended the Philadelphia reunion in 1999, and the Cincinnati reunion in 1998. I am planning to go to a reunion of the Force Recon. I belong to the Marine Corps League, the Order of the Purple Heart, the 1st Marine Division Association, American Legion, Force Recon Association, and the VFW. I am most active in our local Marine Corps League chapter, the "Nittany Leathernecks" which is composed of active duty, retired, and Marine "veterans" like myself. We are an active organization dedicated to community service. Our motto is: "Valiant service is not limited to combat." My best friend Lynn Hook and I were instrumental in forming the Nittany Leathernecks Detachment from its early beginnings in the State College area in 1974. I was awarded a Life Membership in the Marine Corps League in recognition of my "outstanding member recruiting efforts". It was the first time this honor was afforded to a detachment member. I have also been nationally recognized by the Marine Corps League for my detachment historian efforts. I am also a military paraphernalia collector. When I was young, I was very interested in the military. I used to save patches. At the time, I only had to pay five cents a patch. Now those things can sell for as much as $100 -- even more if they are particularly unusual patches. I collect anything that's military, but mainly World War II and Korea items. I have a few things from World War I, but I am not really interested that much in that war. Since the Korean War was so close to World War II, there is a lot of similarity in the equipment since so much used was surplus WWII clothing and equipment. I collect uniforms, hats, bands, stripes, chevrons, patches, shoes, from all branches of the Armed Forces. But I particularly collect Marine Corps items. Military museums sometimes ask me to loan things to them--buckle-type shoes, hats, helmets, etc. I have an extensive collection. I have a hundred uniforms and several thousand original patches. The patches you find now are often not authentic. You can tell. The old ones were made of cotton. Reproduction patches are rayon, nylon, and other synthetics. Our family has a military background. My brother was a captain in the Army. He is a dentist who worked on the teeth of Generalissimo Chiag Ki-Shek (Supreme Allied Commander for China). My brother received a nice silk scarf for doing that. He was in the China, Burma, India (CBI) theater during World War II. I was a sergeant in the Marine Corps, of course, during the Korean War. My son, David, was a captain in the Marine Corps and served in the first Gulf War. Two of my nephews, Richard and Robert Chin, were captains in the Army. My niece, Sally McElwreath , is a retired Navy captain, which is the equivalent of a full colonel. She is married to Rear Admiral Joe Callo, USN (Ret). My nephew, Jimmie Yee, served a tour in the Air Force as a dentist. His son, Wayne, also became a dentist and is serving as a captain in the Army. My grand niece, Cathy Chin, is a major in the Air Force. My nephew, Gil Larson, is a retired Navy captain.

The Marine Corps has always been, and always will be, a part of my life. AddendumRecommendation for Meritorious Promotion

Marine HumorThe following article appeared in the ship's newspaper when Herb Wong deployed to Korea aboard the Marine Lynx during September of 1951...

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Photo Gallery(Click a picture for a larger view) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||