|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||

Joseph Normand RobertsWilbraham, MA "If there was one thing that scared the hell out of me, it was being sent out into the valley at night in front of the MLR with a coil of commo wire and a field phone. I was out there alone, sitting in tall grass listening to every sound. Everything sounded like someone was approaching me. The quad .50 caliber harassing fire with tracers going over me was enough to cast some light, and every shadow seemed to move. " - Joe Roberts

|

|||||||||||||||

Memoir Contents:

Pre-MilitaryMy name is Joseph Normand Roberts of Wilbraham, Massachusetts. I was born June 3, 1931, in Ludlow, Massachusetts on the kitchen table in my parents' home on Prospect Street. I don't know if there was a doctor or midwife present, but back then, many children were born at home. My parents were George and Alice Talbot Roberts. My mother was from St. Hubert, Canada, and my father was from Chicopee, Massachusetts. Mother was here by marriage. I don't know how they met. Father worked in a foundry called Chapman Valve Company in Indian Orchard, Massachusetts. When I was two weeks old, my mother died at the age of 33 from an infection. I had five older siblings: Harvey, Roger, Chic, Alice, and Dianne. Dianne was my oldest sister, and she took care of me immediately after my mother died. She brought me down to my future grandmother (a widow named Mrs. Pauline Carmell) on a pillow to show her the new baby. She and her family of six kids lived in a house at the bottom of the street where I was born. My grandmother (she was not a blood relative) took one look at me and told my sister that she wanted to talk to my father. She was afraid that I was going to die being cared for by my sister. My father had to keep his job to support my sisters and brothers, and he was worried about my 12-year old sister taking time off from school to care for me, so he agreed to let Mrs. Carmell take me in. When my father remarried, his new wife didn't want me, so my grandmother continued to raise me. Grandmother was a fine woman. If anyone is a saint, my grandmother is. To me, she was my mother, although she didn't legally adopt me because she wanted me to have my birth name. My grandmother died in November of 1955. She was 84 years old. All of her children are now dead, too. They lived into their late 80s and mid-90s. I grew up in a great, secure family setting, and I was mostly well-behaved. I saw my father a few times a month, but he died from complications of diabetes and drinking a few years later when I was eleven years old. He had a tough life. I remember that my father had a rough beard and that he was thin. The Great Depression was hard on many, including my birth family. Growing up in my grandmother's house, we were poor, but her daughters had jobs so I didn't realize what poor was. I spent my childhood in Ludlow, Massachusetts, in a neighborhood with Polish, French, and Irish residents who lived in nice old homes. We then moved to Springfield, Massachusetts to live with relatives. I liked Springfield better. I attended school at Robert O. Morris grade school, Myrtle Street Junior High School, and Technical High School. I was lucky and squeezed by to graduate in 1950 with a high school diploma. School was okay. I liked some teachers better than others, and I seldom skipped. I didn't participate in sports or extracurricular activities. I was a skinny kid who hung around with my own friends (and still do with those who are living). There was a big forest preserve near my house, and there I learned survival skills with the help of books and practice with some friends. To earn money, I worked in the school machine shop making small machine parts. I got 60 cents an hour. When I was 17, I also worked in the summer as a leaf picker and hauler of full baskets of picked tobacco leaves for Consolidated Tobacco Company in Connecticut. I worked mostly with other young kids, making 90 cents an hour. I saved my money to buy my first car--a 1931 Ford Model 'A'. World War II broke out when I was still in school. I heard about it from the radio, in the newspaper, and from my grandmother. My brother Roger served in the Army infantry in the European campaign, and my Uncle Ed Carmell was in the Army Air Corps. He flew B-17s in 17 missions over Germany. Both survived. We were still a bit poor, but jobs became plentiful during World War II. I remember that it was hard to get many food items--sugar, pineapple, butter, canned goods, meat, some green groceries, tuna fish, eggs, some baked goods, flour, etc.--you name it. We had to use ration stamps for everything. In school our teachers talked about the war. A teacher in my school taught me how to knit, and I knitted squares for military hospital blankets. My sister's boyfriend was a pilot, and he was killed in the South Pacific. I was young then and didn't pay much attention to the war, but I felt bad for him. I wasn't old enough to join the military, but I still wanted to serve. When the war was over, people were glad. They were a bit worn out with war by then. Army TrainingBasic TrainingAfter I graduated from high school, I first worked for a dry cleaning plant. I then worked for the Springfield Armory as heat treater, making the same arms that I was to use in the future. I joined the U.S. Army on October 8, 1951. I went to the recruiting office in Springfield, Massachusetts, for an interview and physical. I wanted to serve, wanted the adventure of experience and travel, and wanted the discipline of Army training. Many of my friends were already in the service. One was in the Air Force and another joined the Army later. I chose the Army to go into because I didn't like sea sickness and wasn't looking for glory. I just liked the Army. My brother had been in World War II, but he didn't talk about it much. He and his family lived in another city so I seldom saw him. He wasn't aware that I had joined until months later. My grandmother and relatives were worried about me joining, especially after I was sent to Korea later on. I didn't know much about Korea until I got there. Actually, I didn't really think I would end up in combat when I joined. Boy, was I wrong! I traveled to the training camp at Ft. Dix, New Jersey, by bus. It was the first time I had ever been away from home for any length of time. The camp was on flat, sandy ground not far from the coast. It was hot in the summer and cold in the winter, and there were flies, mosquitoes, and bugs in general. That first day, the drill sergeant chewed us all out for gabbing in formation. We were then assigned typical Army barracks with two-tiered bunks. On the second day, we got fatigues and had to attend lectures about military life, military history, and what was expected of us. I think I was assigned to the 364th Infantry training platoon. Basic training was eight weeks, and Korea was seldom mentioned. Like half of my buddies, I thought I was going to Europe. (Ha! You dreamer!) I was assigned to Company E, 3rd Platoon, 364th Infantry Regiment while in basic training at Ft. Dix. Most of our instructors were World War II veterans and career Army, and many of them were black. I had gone to school with quite a few blacks and had some black friends, so I had no problem with having black instructors. They were very good. Everything about our day was regimented--meals, personal hygiene, training, free time, taking care of the barracks, and lights out. Our day began when we were awakened by a loud whistle and yelling at 6 a.m. The barracks had showers, and we washed our clothes by hand. The barracks floors had to be scrubbed by hand. After an initial morning inspection, it was off to the mess hall. Every infraction resulted in KP or other duty, and could very well mean no weekend pass. I got KP duty once for wearing wrinkled fatigues. I was also disciplined for not making my bunk correctly, for having a foot locker not up to par, and once for eating ice cream while on KP. I got banged on my helmet a few times for being out of step. Other forms of punishment were mostly KP duty or guard duty on some spooky remote ammo warehouse--or perhaps the WAC's barracks (smiles). The whole platoon was rarely disciplined for the wrongdoings of one individual, but the whole barracks was punished for things like smoking in the barracks, sneaking in alcohol--and one time for sneaking in a girl. If the discipline was a collective-type discipline, it was done to make all the rest jump on the offender. I didn't have much fun in basic, and there were times that I was sorry I had joined. The discipline and lack of free time was a pain. There were no home passes for the first month of basic, but if we weren't in training and if we didn't have KP or guard duty, our time was free. Our meals consisted of a variety of typical military food. Church was offered, but many were too tired after a week of training to attend. Instructors didn't bother those in worship. Our training was both in the classroom and in the field. In the classroom they taught us about military operations and military history. In the field we learned how to crawl through mud, march, bivouac, and shoot. I already knew how to shoot a rifle when I joined the Army. As I mentioned earlier, we were poor while I was growing up. I had an old single shot .22 caliber rifle, but never more than four or five cartridges to hunt squirrels and rabbits. (My grandmother made excellent rabbit/squirrel stew.) My uncles also hunted. I had to make every shot count. While in basic training at Ft. Dix, I won my company's marksmanship competition and was awarded an engraved silver bracelet. I let my steady girlfriend (now my wife) wear it, and she lost it. Sometimes we were awakened in the middle of the night for night problems to march out to defend against a phantom enemy in full gear. Our training also consisted of watching gory World War II combat films. Our "graduation ceremony" was a 20-mile hike in full field packs to attack a hill held by an imaginary enemy. We had live ammo for the attack. Our long column of G.I.'s was harassed by low-flying Piper Cub planes that dropped one pound paper bags of flour on us to simulate an enemy air attack. By the end of basic training, I had come to appreciate my instructors. They did a good job of making us soldiers. After my training at Ft. Dix, I felt that I was well-prepared for combat. I was more self-reliant, tougher, and had a better outlook on life. Advanced TrainingAfter I completed basic, I was sent to a Signal Corps unit because I had had some radio experience. I had fooled around building radio kits and hi-fi equipment, but nothing exotic. The Signal Corps had their own barracks in another area of Ft. Dix, and the schooling there lasted for sixteen weeks. They taught us Morse Code and military radio operation and repair. I hated it and deliberately flunked out by failing my test. The Major in charge knew it and shook his head. He said, "Well, I guess you want to be an infantryman." He was right on. The Signal Corps just wasn't my 'thing.' I was a bit naive back then, and I wanted adventure. (I got a big wakeup call in Korea.) I went back to 16 more weeks of basic training after already having eight weeks, but I was okay with it. I was in Company E, 3rd Platoon, 364th Infantry Regiment. I surely felt well-trained after that. On April 27, 1952 while at Ft. Dix, I sent the following letter home to Mary and Ade:

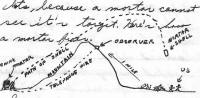

I went home for one week after my training at Ft. Dix was over. I wore my uniform home because I was proud of it. People asked about my training, and my family asked a lot of questions. During my leave, I mostly stayed with my grandmother and foster sister at their apartment, visited old friends, and went out with a girl. I knew several girls, but didn't have a steady. After my leave was up, I went to Bradley Field in Connecticut to catch a flight to Washington State and Ft. Lewis. Nothing really happened at my leaving at Bradley Field other than my grandmother cried a bit. I stayed at Ft. Lewis for about a week in late April 1952. I didn't do much there but hang around. Assignment - KoreaFrom Seattle I was flown to Japan on a Canada Pacific "Empress of the Air" four-engine prop plane. In Japan, I was to undergo two weeks of advanced infantry training. I guess they were in a rush to send me on to Korea, where our outfit was never above 70 percent of full strength. Out of my original group of 42, I was one of only eight survivors when I left Korea. On the plane trip over, I sat next to a former Russian soldier who told me how tough his training was. He said he was left up in a tree overnight in winter for disobeying an order. The flight was pretty normal. We took the North Pacific route to get to Japan, stopping at the last Aleutian island for fuel. I remember that I bought a glass of milk for $1.25. Wow! When we saw some small fishing boats in the water below, we knew we were getting close to Japan. The plane landed and we went by railway car to a base outside of Tokyo where we took our training. I don't remember the name of it. The training we received there was just more infantry training. They taught us how to escape if captured, how to stay away from 'situations' with Korean civilians, what not to eat or drink in the field, etc. We already knew how to use mortars, bazookas, machine guns, pistols, grenades and bayonets, and how to drive a truck, etc. The classroom training we received was more about the Korean culture and what to expect while serving there. There were only two days of classroom instruction and a lieutenant was giving the classes. We didn't have much free time while we were in training. We stayed at the base with what little free time we had, relaxing and reading Army manuals. In some respects it was exciting to know that I was getting closer and closer to getting into combat. In others, it mean that I might not come back--and that was scary. We left Japan in a large Navy LST. LST stands for Landing Ship Tank. They were used in World War II for amphibious landings of troops, tanks, cargo, and vehicles. The Inchon harbor was very shallow and ships could land only at high tide. Being flat-bottomed, LST's could get in at low tide. Three days after leaving Yokohama, Japan, we landed at Inchon in the early afternoon on July 4, 1952. Upon arriving there, I couldn't immediately tell that I was in a war zone. Inchon was a major port for personnel and supplies, and there were quite a few freighters out in the bay. As soon as the landing was secure, we waded ashore and got right on the train that shipped us north as far as it was safe to go by rail. I didn't have much of a first impression of Korea. I just thought it looked poor and beat up. Sitting on the train, I saw lots of Korean kids selling rice wine and other things outside of my window. The train was an old train pulled by a steam engine, and it had cars similar to the Pullman-type. The seats were hard wooden bench-type seats. I am not sure about the tracks, but the steam engine was like the ones in use when I was a kid. A sergeant came into our train car with a case of M-1 ammo and put it in the center of the car. We asked what it was for and he said that they had been having trouble with snipers taking shots at the train on the way north. (Our rifles were not loaded at the time.) We were quite surprised about the infiltrator enemy snipers. We thought this area was relatively safe, but we were on alert during the trip. The train made no stops and went straight through to Uijong-bu. While traveling north, I saw a few natives along the roads, but everything was flattened. There were no towns--just rubble. Once we got to the replacement (repo) depot, we each received our individual assignments. From there I went by truck to my company, which was located close to the front. I was the 'new' guy, and I knew no one. I was assigned to a front line bunker in Kumwha Valley with one other GI. I had no choice as to my assignment, but it was what I was trained for. The weather was warm when I arrived, but the winter ahead was very cold. It was a good thing that I was from New England. The weather was like home. We were in mountainous terrain, but there was almost no vegetation. It had all been blown away by enemy artillery and mortar fire. There were bunkers (sometimes called hootches), trenches, and foxholes all around. Not long after I arrived, we were assigned to lay barbed wire across a ravine one foggy morning. The fog suddenly lifted and the Chinese observed us. That was my 'baptism of fire.' They started dropping mortar rounds on us and we all ran up to a paddy dike and dove over the other side. No one was hurt. That was my third day in Korea. My sergeant said, "Roberts, you just earned your CIB," and I didn't know what the hell he was talking about. The C.I.B. stands for Combat Infantry Badge, awarded only after coming under enemy fire. During those first few days on the front line, we got shelled by enemy artillery and mortars. I didn't see too much. I was too busy ducking. I had moments of fear (we all did), but you would be surprised at what you can get used to when you have to. I was a private, so sergeants and non-commissioned officers (NCO's) gave me my orders. Quite a few of these veteran combat soldiers were World War II veterans, and they were very good at what they did. They taught me what to be careful of, to keep my head down, that I was not to walk around outside the trench or bunker, and about enemy tactics. In my "on-the-job training," I learned how to get shot at and shelled by the enemy, and how to keep my cool in tight situations. Actual combat was a whole lot more dangerous and nerve racking than the war stories I had heard prior to Korea. The war stories were a long way from reality. Probably Saving Private Ryan is as close as anything I have seen in the movies that gives a good representation of actual combat. The movie Band of Brothers also wasn't too bad. I was personally armed with an M-1 rifle and hand grenades, and there was a machine gun and M-1 carbine in my bunker. On a night combat ambush patrol, I had a Thompson submachine gun, hand grenades, and a knife. About three weeks after I arrived in Korea, I saw dead Americans and dead enemy for the first time. I felt badly about the American dead, but not so for the enemy dead. Later on, it didn't affect me much--I got so used to seeing dead bodies. I lived with three dead Chinese soldiers in a bunker on Pork Chop Hill for two days. I recall walking down a deep trench and smelling something foul. It was two leg bones sticking out of the trench wall about three feet from the top. My buddy and I were glad to travel on. I also remember going out on a patrol and coming across a dead American in a bunker with several dead Chinese around him. On the Front LineDuring the first three months I was in Korea, we moved on a regular basis along the front to different positions. We were very mobile, to say the least. We never spent two weeks in one place. On the central front--the Kumwha Valley, we were on hills with names such as T-bone, Three Sisters, Hill 200, Spud Hill, Tap-tap-San-dong, Erie outpost, Arsenal outpost, and others whose names I have forgotten. They were mostly enemy hills or hills that were taken and then lost. An "outpost" was a hill out in front of the Main Line of Resistance (MLR), usually occupied by U.S. troops. They were much closer to the enemy, and they were dangerous. The men out in the valley on listening posts alerted the front of any enemy activity. It was a very dangerous, scary job. If there was one thing that scared the hell out of me, it was being sent out into the valley at night in front of the MLR with a coil of commo wire and a field phone. I was out there alone, sitting in tall grass listening to every sound. Everything sounded like someone was approaching me. The quad .50 caliber harassing fire with tracers going over me was enough to cast some light, and every shadow seemed to move. Every half hour I had to blow into the phone to check in to the MLR. I was very relieved when in early dawn I was able to return to my nice (?), safe (?) bunker. We were seldom below the 38th Parallel except when in reserve and once when we were sent to Koje-do enemy prison camp. The outfit there was having problems with the North Korean prisoners, so we were pulled off the line and sent there to help. The North Koreans were very fearful of front line infantry combat troops. We were there about a month as I recall. We put down small riots--firmly. We didn't have much trouble after a while. We used to choose compounds at random to raid late at night to catch prisoners trying to make weapons. On one raid we came to a long barracks type building and, as the door was opened by two other men, I had to run through the barracks. Well, some prisoner was on his way to the latrine and I ran smack into him and knocked him flat on his butt. I don't know who was more scared--him or me. In the valley front, enemy artillery once blew three layers of sand bags off of my bunker. I had been a point man on a night 35-man combat ambush patrol, and was exhausted. I had crawled into a rather small machine gun bunker and had fallen into a deep sleep, alone in the bunker. The explosion never woke me up. I was awakened by shouting and a ruckus outside the bunker. My buddies came down to see if I was dead. I stuck my head out of the bunker after pushing the machine gun out of the way and noticed that the ground around it was a bit chewed up. My buddies were glad that I was okay, and I crawled back in and went to sleep again. (Sleep on the front was precious.)

On another section of the front line, the only small tree around was cut in half by an enemy artillery round. My poor tree, which was just outside of my bunker, fell into the trench. It was a pretty close hit. There was heavy enemy fire and I had buddies who were killed and wounded there. One was a full-blooded Navajo Indian from Navajo County, Arizona. Pfc. Franklin T. Roosevelt (yes, his real name) was killed during a Chinese attack on October 6, 1952. When I returned to the States, I called Frank's family and sent them his pictures. The other, whose name I cannot now remember, was wounded on a night combat patrol. The wounded were taken off the line down to where a chopper could land with some safety, and the badly wounded were taken out by chopper. Several others were killed and wounded during this enemy attack, but they were new and I didn't know their names, or they were not in my squad. I once asked a buddy who had been in Korea a few months longer than me why the others in my unit didn't seem friendly. He said, "They don't want to know you too well. They have seen too many killed and it plays on them." Other fatalities stand out in my mind, too. I was on Erie outpost one time when a mortar round hit as one of our men was just leaving a bunker. It exploded on the top edge of the trench and a fragment caught him in the neck. He died before he could be helped. A young kid. One time a new replacement started to cry. He had come up a few days earlier, and he was at a firing position in the trench just outside of our bunker when a large caliber enemy artillery round hit about 15 feet above the bunker. It showered him with dirt and frags. He stumbled into the bunker with tears streaming down his face and shaking like a leaf. It scared the hell out of me also, but I had been on the line for some time and was a bit used to it. The explosion shook the bunker. I told him to stay in the bunker for a while. There were times when I, too, had felt in great personal danger on the front line, such as being point man on night combat ambush patrols into enemy territory, leading one of the many attacks on Pork Chop Hill, and being in combat on Heartbreak Ridge. I was just plain scared. They were talking peace, and I hoped it would be over soon. On October 23, 1952, I sent the following letter home from Kumwha, North Korea to my grandmother's daughter Mary, and her husband Ade Laperle in Indian Orchard, Massachusetts. I wrote to them because they used to read my letters to Grandmother, who was in her late 70's when I was in Korea.

The enemy that I saw were mostly young, although there were a few older ones, too. Nobody wanted to be taken prisoner by them because a North Korean unit shot some of our men that they had taken as prisoners. They were armed with burp guns (a machine gun like the Thompson sub machine gun, but not as well made), and an assortment of rifles and grenades. They were fair fighters. They fought in waves (mass attacks, wave after wave), costing them heavy losses. My unit was never attacked like that, but many others were. The enemy we saw were mostly small bands probing our lines for a weak point. The wave attacks were on Pork Chop Hill and Heartbreak Ridge. Sometimes we could tell an attack was coming because we could smell the garlic in the air. The North Koreans loved to eat garlic. One day I was in a bunker with two other G.I.'s on Arsenal Outpost. We were on a 'finger' that jutted out toward the Chinese position. It was primarily an artillery control bunker, and it had maps of our immediate front area. It was a quiet day and we were relaxed. Suddenly we heard old music from the 1940's from a hill right in front of us and a Chinese person who spoke excellent English. He proceeded to tell us about home and how we shouldn't be in Korea. He then threatened us by saying, 'If you send artillery on this position, we will return twice as much on you." Well now, I didn't take to be 'threatened' so I plotted his approximate position on one of the maps and called back to our artillery for a marker round (155 ) of white phosphorus (willy peter). It came in near enough and I called for four rounds of HE (high explosives). My two buddies said, "You'd better be damned sure about this, as it's going to come in real close." And it did. It shook our bunker, but it also knocked out the Chinese blabbermouth. We waited with apprehension for the return enemy fire, but it never came. Fighting was mostly in early morning or at night on combat ambush patrols, but one time a general was entertaining some big news group and sent one of our platoons out in the front to simulate an enemy attack. The North Koreans spotted them and hit them with artillery. One man took a frag through his right forearm and I saw him with the bone sticking out of his forearm. The general was severely reprimanded and was relieved of front line duty. No others were hurt in this incident. One time a Marine unit was on our right flank. They were good men and we had no conflicts with them--in combat, we were all the same. I recall writing home for some mantles for my Coleman lantern that I used in reserve. They came when I was up on the Kumwha Valley front. Don't ask me how he found out I had them, but one day a Marine came up the trench to my bunker and asked if I would share some of the mantles. I said sure, and I gave him four of my eight. He left one happy Marine. I hope he survived. There were also some troops of other nationalities serving near us. There were Republic of Korea (ROK) soldiers who were "okay" as good fighters, and then there were the Turkish soldiers who were fearless. If someone asked a Turk soldier to see the knife he carried, he had to cut himself first. If they drew a knife, they also had to draw blood. ROK troops were assigned into our units and we got along just fine with them. We didn't have much contact with non-military South Koreans because Korean civilians were not allowed within 20 miles of the front lines, except if employed by the military. They did a multitude of work, such as unloading/loading trucks. They served in the rear areas, but were never close to the front lines. I was never involved in hand-to-hand combat as some in other companies were, because the Chinese got knocked off before they close enough to us for that kind of fighting. I was, however, wounded while leading an attack on a small hill. We were taking enemy small arms fire, so we dove into a ravine near the base of the hill. I knew we couldn't stay there, so I jumped up and ran up a narrow draw. An enemy mortar hit about 20 feet ahead of me and a fragment hit me in the chest, knocking me flat on my butt. Fortunately, I was wearing a newly-issued armored vest and the frag didn't go all the way through--but it scared me and made a hell of a dent in the vest. Another time, I was leading a 35-man night ambush patrol when I was bitten by a snake. It was non-poisonous, but it made my arm swell up and they shipped me back to a MASH unit for treatment for a week. Wow! Fresh eggs and bacon for breakfast. I was in Heaven. Having been hit did not cause me to be more cautious in the hours and days that followed. It was no use being overly cautious--if you got hit, you got hit. I got over the shock of being hit, but I never forgot it. When we dug in for the night, we were protected by trenches and bunkers and foxholes. We also received fire support from Navy and Air Force jets, and from the ground in the form of mortars, tanks, recoilless rifle units, and quad .50 caliber machine guns mounted on half tracks. The tank support was very good. Tank and air support were used when an enemy attack was expected or underway, which was several times in the Kumwha Valley front. We were kept well-supplied by trucks at night, although the Chinese did ambush one of our mail delivery trucks one night as it was coming out of Erie Outpost. I didn't hear if anyone was killed or wounded, but I do know that support was fast in arriving to help them. I remember that some of the mail was salvaged. The Korean War caught the U.S. Army with its pants down. It was unprepared for war. Almost everything we had or used was of World War II vintage, including rifles and ammunition that had been made as much as 10 years before. Some equipment was stamped 1942. In the summer we wore green fatigues, whereas the enemy wore light tan fatigue-type clothing. The enemy wore tan padded uniforms in the winter. Our winter gear wasn't that good, although later we started getting insulated boots (after I got some frostbite) and warmer parkas. In the bitterly cold weather, we had to degrease the machine guns so they would fire okay, and we had to do the same thing to our rifles. When the weather was from 30 degrees to 22 degrees below zero, it was so cold that the oil on the machine gun froze up. Because of my marksmanship, I was pulled off the front and sent to sniper training for a week in a rear area. I was one of the few who had the new night scopes that let one see in the dark. Everything looked green. It was mounted on an M-1 carbine and all my buddies had to have a 'peek' through it. Among the battles I was in during 1952-53 were those to take or hold Pork Chop Hill on the central front and Heartbreak Ridge, Erie and Arsenal Outposts, and Jane Russell in the Kumwha Valley. The peace talks were underway and those areas were just bargaining chips for the enemy. Each battle for these "bargaining chips" still stands out in my mind after all these years. They all involved artillery and mortar attacks in the pre-battle phase, enemy troops, U.S. artillery strikes, air and tank support, enemy artillery, and mortar fire during the battle, and picking up the dead, enemy guns and ammo when the fighting was over. They also included rainy weather, cold C-rations, and lack of sleep. Some of our efforts to accomplish our objectives during these battles were successful and some failed due to heavy resistance. Either way, whenever the fighting was over, I felt I was lucky to be alive and in one piece. Daily LivingOne word can describe life in a foxhole or trench: miserable. One time I was told to get into a foxhole located on a saddle-like hill near the Chinese lines to observe them. It could only be approached at night as it was too dangerous to get there by day. I had to stay there all day until relieved at night. That foxhole had about three inches of water in it and the enemy kept lobbing artillery rounds about twenty feet over my head. They weren't trying to hit me, but rather they were trying to hit something on the next mountain. It was very unnerving. A bunker was dug into the side of a hill mostly, and was reinforced with wooden beams, metal rails, and at least six layers of sandbags. There was a trench leading in and out, and several firing ports. Life in a bunker was better than the trench, even though it was very Spartan. There was a commo wire mattress between two steel rails, nice sandbag seats, a great dirt floor (sometimes 'juicy' after a rain), and rats and assorted bugs. If conditions permitted, we washed socks in our helmets and shaved the same way--if we could find a razor. (View my Korea photo album and notice the "clean" fatigues.) We got to shower once a week, conditions permitting. In a rare show of kindness, the Army moved a large mess tent kitchen up just behind the front. It was spotted by an enemy artillery observer a few days later and a volley of enemy artillery rounds blew it up, killing the cook and two helpers, and riddling the pots and pans with frag holes. We never ate the native food because we were warned about its safety. The food we ate was C-rations, mostly dated from World War II. I missed milk, bread, hamburger, good coffee, steak, tea, fresh veggies, bananas, fruit, and the home cooking that I had in the States. I missed fresh glasses of milk the most. In Japan I bought frozen milk, but it didn't taste like the milk back home. The best thing I ever ate in Korea was Thanksgiving dinner at Koje-do, where we were served turkey with all the fixings. Since I was usually on the front line, that Thanksgiving was the only time I celebrated an American holiday in Korea. On holidays, we usually thought about home and wished we were there. I turned 22 in Korea, but it was just another day--nothing special. Frank Yakashima had a good sense of humor and he and some others kept us laughing, although not too many humorous things took place in Korea. I remember a funny story about the Chinese. One day I was in a bunker with a .50 caliber machine gun that we used as a long range sniper rifle to fire one shot at a time. I was watching some Chinese on a hill directly in front of us when, lo and behold, a young Chinese girl jumped out of a trench wearing a bright yellow skirt and did a dance for us. I reported it to my Sergeant and he and others came up for a look. Well, my binoculars disappeared into other hands and they all had a good look. By the time I recovered my binoculars, she was gone. Of course, no one shot at her (smiles). It was funny to see her in that yellow skirt. We also laughed at a Red Cross person who came up to the Kumwha Valley front one day. He didn't stay long. He was a nervous wreck. We received mail regularly if conditions permitted. My aunt and uncle, sister, and other relatives wrote to me. Since my grandmother was then in her mid-seventies, her daughters wrote for her. They also sent me packages, and they usually arrived in good condition. I remember receiving canned chicken, oatmeal, canned goods in variety, fruit cakes, newspapers, and warm gloves. Other guys in my company received a vast variety of goods, particularly Italian sausages and other ethnic foods. The only thing I actually asked for were the mantles for my Coleman gas lantern that I used in reserve and which I have already written about. My aunt sent them to me. I never came within 50 miles of any type of church. Only in rear areas did I see American women--and they were mostly nurses. We rarely saw any Korean prostitutes either, and rarely talked to the natives, as civilians were not allowed any closer than twenty miles from the front. They were also kept out of reserve areas. We had some contact with a very few natives at the Koje-do prison camp. What natives we did see were mostly war-displaced natives and kid beggars. Most lived in shanties. I really didn't think about whether or not their country was worth fighting for. I was there and that was it. USO shows were not about to come up to the front, and while I was in reserve there were none close enough to attend, so I didn't get to see any of those. I didn't drink or smoke (never have), so in my spare time I slept and wrote home. Then, after six months in Korea, I got a six-day R&R to Sasebo, which was located on the southern-most island of Japan. I was sent by truck to a small rear area air base, and got on a flying boxcar to Japan with two other guys who I did not know. Sasebo was an old Japanese city with some manufacturing plants and old Buddha statues. I took $100 US dollars with me, which converted to 10,000 Japanese yen. I got a room (nothing fancy) at the new Kukora Hotel, and I slept soundly in a real bed. I also ate like a king at the base PX. I bought and sent home a silk jacket, a fancy cigarette lighter, silk pajamas, and a silk scarf. A Japanese waitress at the PX thought I was cute (the poor thing was in serious need of glasses) and showed me the local sites and took me to a movie. I saw quite a bit of the Japanese countryside and the Japanese people. The Japanese culture was quite a bit different than the American culture, but it was becoming Americanized. R&R was a welcome break. No one was taking pot shots at me or trying to blow me up, and it ate up time for my 36 rotation points. (We got more points for being on the front lines.) I hated to return to Korea. Going HomeIt was the first part of May 1953 when I was informed by my sergeant that I was being rotated home. I had mixed feelings. I was sad to leave my buddies, but glad my tour was over. For the last hours I was with my unit, I kept my head down. I wrote this letter home to May and Ade on May 8 from Outpost Erie:

On the back of the envelope, I wrote: "Go letter go -- because I can't." I was taken by an APC, then by truck to the departure point for the usual Army checkout for those going home. I boarded an old Liberty ship, leaving Korea as a PFC. G.I.'s from many different outfits were on the ship with me. We saw replacements coming in as we were leaving, but they were too far away to talk to. Then the ship left Korea on a non-stop, week-long trip back to the States. The trip wasn't too bad, but many got sea sick, including me. There was no entertainment on board, and I had some KP duty. I was glad to see mainland USA. The ship docked in Seattle, Washington, and there were lots of civilians there to welcome us. When I disembarked from the ship, I walked over to a Red Cross van (I never saw one in Korea) for a doughnut. Then I got on a bus for Ft. Lewis. During the next 24 hours, I ate, got lots of sleep, counted my blessings, and thought of those who didn't come home. I finished out my time in the Army at Ft. Monmouth, New Jersey, where I was assigned general work, but no KP. Some guys go a little wild after returning from war, but I didn't. I had had enough excitement. Did I think about re-enlisting? No way! I was discharged on October 7, 1953. I lacked just one day of having served two years in the U.S. Army. (Back then, one could enlist for just two years.) For my Korea service, I received the Combat Infantry Badge, a battle ribbon with three battle stars, and a Korea Service ribbon. I'm proud of them and our kids like to look at them. Final ReflectionsI had no problems adjusting to civilian life after leaving the Army, but going to Korea took the "kid" out of me. It made me self-reliant. I was more serious and not such a wild kid anymore. I was more responsible, thinking more about my future. After I was discharged I took it easy for a month and then went looking for a job. I got a job at Monsanto Chemical Company in Indian Orchard, Massachusetts, and that was the job I settled into. I stayed there until 1989, when I retired. I married Margaret Jean "Peg" Gauthier and we had children Joe, Sharon, Greg, Mike, and Jim. After retiring as a foreman at Monsanto, Peg and I now live on five acres on Wilbraham Mountain where we grow tomatoes, walnuts, cherries and plums. I had some frost bite to my left foot, but I have no permanent disabilities associated with the Korean War. For me personally, the hardest thing about being in Korea was being away from home, the danger, enemy fire, losing friends, and the weather. Without a doubt, my training saved my life in Korea, and serving in the Army made me tougher, more able to face problems, more understanding of others, and more able to make decisions and accept responsibility. I think the United States should have sent troops to Korea in 1950. I guess we had to stop communist aggression, and at least the South Korean people are free. I think the U.S. should still have troops in Korea to let the north know not to attack the south again. Would I ever go back to Korea on a revisit? No way! It's hard after all these years to recall everything about my Korean War experiences. I've forgotten many names of those I served with. My memories now of Korea are of combat, lost friends, the loneliness and sadness, miserable living conditions, fear, and rats. To me, anyone who had to live under the conditions the infantry did in Korea was a hero. If a student sees this memoir on the Korean War Educator someday, I hope he or she will know the sacrifice that the troops made, and understand that many of those heroes never came home. I don't really know why the Korean War is called "the Forgotten War." Perhaps it is because it wasn't a declared war. I know that for 25 years after leaving Korea, I very seldom talked about it, even to my new wife. I told our kids about it at their urging. I have lots of pictures from when I was in Korea and our oldest son convinced me to post the photographs on the internet. He runs the website for me. After the website opened, I contacted the Korean War Educator and decided to answer questions that resulted in this memoir. In the warm months while I was in Korea, I often wrote home. There are fewer letters from the winter months because it was too cold to write and my fingers would freeze up. My family kept the letters I wrote to them and I still have them today. Some of them are in the Addendum below as part of my Korean War memoir. Addendum

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||