|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||

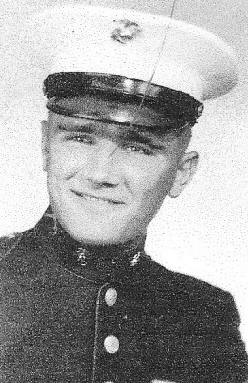

Edward Charles PlackoOregon, OH - "I had a guardian angel when they transferred me over to the mortar platoon. That angel was still there when I got wounded, so I can say I was lucky. If I had stayed in the rifle platoon I could have been killed or wounded like some of the others were. " - Edward Placko

|

|||||||||||||||

Memoir Contents:

Pre-MilitaryMy name is Edward Charles Placko of Oregon, Ohio. I was born January 25, 1932 in Cleveland, Ohio, the son of Andrew and Mary Gaul Placko. Both of my parents were from Czechoslovakia. My dad's family moved to the States when he was about 12 years old. His main job was as a punch-press operator. I was raised and went to school in Cleveland until I was almost 16 years old, and then we moved to Genoa, Ohio, which is about 13 miles from Toledo. I attended school during World War II and remember the paper drives and putting crushed tin cans out on the curb to be melted down for the war effort. There was a sense of patriotism in our family, even though my dad did not serve in the war. He wasn't a punch-press operator then. He was a core maker for airplanes, so he was deferred because of his job. If he would have quit that job he would have had to go into the service, but they didn't want him to quit because they needed him there. I finished two and a half years at Genoa High School, graduating in 1950. While I was in school I played sports, but I worked also. I delivered papers for a couple of years and then when I got old enough, I worked in a bowling alley setting pins. It was better than selling papers. I made around $40 a week, which, at that time, was a lot of money. It was hard work because I set two alleys at a time and I got hit by pins once in a while. My knuckles swelled and my fingers were damaged (I now have bent finger bones) from picking up pins--one here, one there. Sometimes I picked up three pins in each hand and sometimes even four. After graduating from high school I worked in a glass factory. I quit that and went to work for Otis Elevator installing passenger elevators in office buildings. I was a helper. I only worked that job maybe eight months. When I was 18, I also traveled to Florida by myself. There was a tryout with the Washington Senators in January and I was down there the whole month. They told me I should play another year of baseball and then come back the next year, but I enlisted in the Marine Corps instead. Joining the Marine CorpsI joined the Marine Corps on September 6, 1951. At that time, when a boy graduated from high school he knew it was almost automatic that he would go into the military of some kind. I was getting close to being drafted and I didn't want to go into the Army. I had wanted to be a Marine ever since my one uncle, George Gaul, was a Marine. He was my mother's brother. When he came home on leave he wore his dress blues. That hit me right there and that's what I wanted to be. My parents didn't really like the idea of me enlisting in the Marines, but they knew that I would be going someplace. I signed up before my dad even knew it. My buddy Vince Harsanje and I enlisted. We both went to boot camp, but we parted company when I went to Camp Pendleton, California for advanced infantry training and he was sent down to some school in Florida. He went into the Marine Air Wing. When I was in Korea I got a letter from him every once in a while to let me know that he had been promoted. In three years he got out as a Staff Sergeant and I got out a Corporal. When I left for boot camp I went from Toledo on a bus to Cleveland. I was sworn into the Corps there and then we went by train to Buford, South Carolina. We stayed there overnight, went on to Yemassee, and then got on a bus there to go to Parris Island. Boot CampI remember that we all got yelled at that first day. He wasn't our drill instructor, but the guy in charge of us yelled at us when we didn't move fast enough or whatever. They started yelling at us from the first second we got off the bus. I often wondered, "Am I in the right place?" They had us shaking. I was punished once for slapping a sand flea. When we came out of the mess hall we were supposed to stand in formation. We had our spot and we stood in that formation until everybody assembled there. Then we marched back to our barracks. When we were standing at attention we were not supposed to do anything but just stand at attention. That day a sand flea was getting in my ear. I stood it for so long and then I slapped it. Well, my drill instructor saw that and I got punished for it when we got back to the barracks. Not only did I get punished, about four of us did. I don't remember what they did, but I remember that we had to pull our rifles up on top of our wrists and keep them there. I don't remember how long we had to hold them there, but it was quite a while. I don't know if it was as long as an hour, but whatever it was it seemed longer, and we started getting tired. When the drill instructor went into his room we dropped our hands down. As soon as we heard him coming back into the room, we put our rifles back up on our wrists and held them there again. He knew we weren't holding them up there when he was out of the room because nobody could hold his rifle on top of his wrist for that long without dropping it. He got in our face, but it wasn't bad really. That was the only time I got yelled at. Others got in trouble, too. Sometimes all of us were punished and we all had to scrub the hallway with our toothbrushes and a bucket of water. Our barracks were one here, one there, with a big hallway through the middle. At the end of the hallway there was a door. The drill instructor marched the whole platoon in that hallway, shut both doors, and then we had to get a bucket of water, soap, and a toothbrush and everybody had to bend over trying to scrub the floor. It was almost impossible, but we still had to get it done. When we bent over we would hit a guy with our butt or he would hit us with his butt. It was just a mess. We were taught discipline in boot camp. Whatever we did we couldn't satisfy the drill instructor. Even though everybody thought they were doing the right thing, it was the wrong thing. But we learned to follow orders, whether we thought they were right or wrong. We had to do it their way or it wasn't the right way. Because we learned to follow orders during those ten weeks of boot camp, it helped us in Korea. There were guys who didn't make it out of boot camp. There were guys who didn't know their right from their left and they messed up all the time. When they did they took them out of our platoon and put them in some type of a training platoon. I forget what they called it. A couple of those guys came back, but the rest of them didn't. We had one guy who washed up completely and they sent him home. I don't remember why. I guess the Marine Corps did that to get rid of the weak ones. When I was done with boot camp I felt like I could have flipped a little. I felt like I had accomplished something that not everybody could. When I walked out of boot camp, my chest was really sticking out. I thought, "Boy, I made it through boot camp. I can do anything now!" We got a ten-day leave after boot camp. I went home and then I returned to Parris Island after my leave was up. They put us on planes and took us all to Camp Pendleton for advanced infantry training. Advanced Infantry TrainingThey put us in squads and we went through all kinds of maneuvers that we would probably use in Korea. We went up and down hills, had cold weather training, and went through obstacle courses. I got to go home on Christmas leave and then when we got back to Camp Pendleton they took us up further north into the Sierra Nevada mountains to a place called Pickle Meadows for the cold weather training. We had night training there. They had Marines stationed there who were supposed to be our "enemy." Their job was to harass us at nighttime. We slept in shelter halves, putting two halves together to make a tent out of them. Sometimes we had to dig a cave in the snow and get in there to keep warm because it was pretty cold up there. On the General GordonAfter returning to Camp Pendleton from Pickle Meadows, we shipped out the last couple days in February or the early part of March. I think we got to Korea about the 16th of March, 1952. The name of the ship was the General Gordon, a troop transport that carried about 1500 men. I had never been on a big ship before. I thought I was going to handle the trip well, but when we left San Diego everybody went up on deck to watch the skyline and wave goodbye. The ship didn't have stairs--there were ladders. While I was going up the last flight of ladders somebody vomited down the ladder. Pretty soon my hand was gushing in it. Oh boy! Then when I got up on deck I saw quite a few guys all over the rail throwing up. Pretty soon I did the same thing. I was actually pretty good as we got underway until we hit rough weather one time and the ship started tilting first one way and then the other. It started not only rocking up and down, but also sideways. I got sick that day and so did others. There was one kid who was sick from the time he got on the ship until the time he got off. We slept in what looked almost like stretchers hung three to four high. As we were laying there, if we turned over we hit the guy above us. This kid had his helmet hanging right there all the time so he could throw up in it. He could hardly make inspections half the time. That dude was sick. I don't remember any entertainment on the ship. I remember playing cards and stuff like that on deck. Everybody on that ship knew where they were going. We were going into war and we didn't know what was going to happen. It isn't that I didn't want to go--knowing that everybody else was going kind of took the feeling away a little, but I did ask myself, "How did I get into this?" We stopped in Kobe, Japan, where we had three days liberty. We had to report back to the ship every night, but the next day they let us go off again for so many hours. I chased girls and went sightseeing, although we were a little too far away from the site of the destruction caused by the A-bomb during World War II to see that. Howe Company, Seventh MarinesWe landed at Sutur-ri in South Korea on March 16, 1952 as part of the 18th replacement draft. Although I have trouble finding it on maps, I know it was somewhere at the bottom of the Korean peninsula. They transferred us from the General Gordon onto LSTs or some kind of landing craft that opened in the front end, and we landed in Korea in the daytime. My first impression of Korea was that it didn't look too great. It was dingy and dirty looking. I didn't question whether it was a country worth fighting for. The way I was brought up it wasn't that I was fighting for that country. It was my country I was fighting for, not their country. My government was sending us over there to do a job, and that's what I figured I was there for. I remember seeing workers on the dock and things like that, and I remember seeing military trucks. We were put on trucks and moved out to join our various companies. At the time of my arrival in Korea I didn't yet know where I would be assigned. That happened somewhere along the line later that night. I was assigned to Howe Company, 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines. Two of us, a guy named Robinson and I, were sent up there as replacements. I didn't know where Howe Company was at the time except it was "up on line someplace." I was a replacement rifleman. When we got to Howe Company the men were on line in bunkers. At that time there was no fighting going on. We were just staying in our position up on line. We were up on a pretty high hill, but I don't remember the height of it. When I first got to Korea I wasn't afraid because it was light out. But then in the first night I stood in my first watch by myself, and I was scared. I was scared of somebody coming up the hill and jumping me. I remember we had a bunker here and one there and we had a little trench that went between them and right in front of the bunkers. That's where we stood our watch. I was afraid to move, thinking that somebody might see me and that would be it. I wasn't afraid that one of my own people would possibly mistake me for the enemy, I was afraid of the enemy. I had heard stories, and then I thought I saw and heard things. I heard shots going off in the distance and once in a while I heard a bigger round go off. I didn't know at the time what kind they were, whether they were artillery or mortar. Mostly I heard rifle shots. But my first watch was pretty good and it went by. I still didn't feel "seasoned" after that first night. It took a little while. I remember that when I went to wake up the next guy that was supposed to go on watch, I went into his bunker. They had a little fireplace built in there and they just had a little flicker of a fire going with a candle. I couldn't see the guy. I saw his boots, but I couldn't see his head. He had gotten into his sleeping bag with his head where the feet were supposed to go and his boots were hanging out of the head part. It was March when I got there and it was still pretty cold. I think being scared and cold at the same time made it worse. It was colder than Ohio, but don't ask me the temperature. I just know it was cold and there was snow on the ground. They had taken our cold weather gear away from our draft while we were on the ship because they said the spring thaw was coming and we wouldn't need cold weather gear. We just had our boondockers and our yellow leggings. When our feet got wet slushing through mud and everything, it was pretty cold. East Coast to West CoastThe first week was uneventful, so I felt pretty good about that. Then the Republic of Korea (ROK) army relieved us and they moved our whole division to the west coast. When we got off the line we started marching to our reserve area, Camp Tripoli. The whole division was moving. As we marched we saw an army camp and our whole squad went to that camp to see if we could get something to eat. We went into their mess hall and they fed us. Well, I'm a slow eater. I saw everybody walk out, but I thought they were just walking out of the mess hall. But they wanted to get going and went on, leaving me by myself. I had been in Korea for about a week and I was now on the road by myself. You'd better believe that it made me nervous. As I walked on, a Jeep came from the direction I was supposed to be going. The driver stopped and said, "Are you going to Camp Tripoli?" I said that I was and he told me that he would pick me up on the way back if I was still walking. Pretty soon there he came, but his Jeep was loaded with supplies in the front and back seats. You know where I sat? I sat on the front fender with my rifle strapped on my back. I had the ride of my life. I thought I was going to fly off that thing. Oh boy! We up the hills and down the hills. Roads weren't "roads" over there. They were muddy and full of chuck holes. There was a light right on the fender that looked like an old parking light on an old car. I hung on to that as we bumped along, and tried to hang onto the edge of the hood for the 20 minutes that it took us to get to Camp Tripoli. After that I tried to keep up with the company so I would never have an experience like that again. I think we just stayed at Camp Tripoli overnight before they put us on trucks and we all headed toward the west coast north of Seoul. I can't remember a town or anything that was around there. Our company was going in reserve at a place they called Camp Rose. We were there for about 30 days or something, more or less setting up the camp. We also had training like we would have had every day if we were back in the States. They treated us like we were all new guys, sending us out on infantry training charging up hills and things like that. At night we had some entertainment. They showed movies and different guys had boxing matches. We were eating meals. We were getting mail. I don't remember whether we were getting showers all the time or not. My mother wrote letters, and once in a while she sent packages of cookies or something like that to me. Back on the LineFrom Camp Rose we went to Camp Myers and from there we went into our new position up on the line. For almost two months I didn't experience a firefight. Then when we went up on line around Hill 229, we still didn't experience any fire right there. But when we went out on patrols or raids, we ran into firefights and we started catching incoming rounds. One night they heard us and started dropping mortars in on us. A lot of things that we were told in boot camp about combat were right and prepared us quite a bit for Korea, but there were things that they didn't tell us, too. We learned how to take care of ourselves in combat by on-the-job experience. For instance, if we started to get incoming rounds we had to know where to dive to get out of the way. I can remember one raid when we got to 229. They gave me a Browning Automatic Rifle or BAR (which is heavier than an M-1), and I had an assistant who helped carry some of the ammo. That night we started getting a lot of incoming rounds. When my assistant stood up on top of a big rock on the side of the hill I hollered at him, "Bobby, come on down here by me." He came down by me and the next round landed right where he had been on that rock. From then on he always told everybody that I had saved his life. We all learned from experience that sometimes when we started to get incoming rounds there was no place to hide. I took off my helmet a couple of times and used it to scrape the ground to make a little slip trench just big enough to get part of my body in it. We didn't have our shovels or any entrenching tools with us for something like that. Making a slip just big enough to make an indentation could make a difference when it came to saving our lives. If we were laying in a little indentation and a round hit nearby, the fragments would go straight across over our head and we had a little protection, whereas if we were just laying on top of the ground they might get us. There was no commanding officer telling us what to do up there on the line. We just looked out for each other. We might have only known each other for a couple of months in Korea, but when we now get together for reunions it's like we've known each other all of our lives. It's a close-knit group of guys. Eugene "Woody" WoolridgeThe first American Marine that died from our platoon after I got to Korea was a radioman named Sgt. Eugene "Woody" Woolridge. He was also the first friend of mine that got killed. It happened on June 26, 1952 when we were on a patrol. He was our squad leader and I was probably 10 to 15 yards behind him. Our mission that night was to go on patrol to an outpost, stay with the guys that were there for a little while, and then go over to another outpost and stay with them the rest of the night and come back in the morning. It was dark and we were on our way from OP2 (we called it OP Green) to the other outpost when our guys started stepping on mines. Another friend of mine, Gale Miller, thought he saw some movement up in the hill, so everybody stayed put because we thought we might be in a mine field. I was the second to the last guy back in the column and Gale was going to run back and tell me. It was about 2 or 3 o'clock in the morning and he didn't want to yell at me and let everybody know that we were still there, so he started walking back. He was first hit ion the hand by shrapnel from the same landmine that killed Sergeant Woolridge. A few seconds later Gale stepped on a mine and lost his leg below the knee. I found out 46 years later that he lost both of his eyes, too. We had to stay there all night with the injured because they wouldn't send helicopters in to get Sergeant Woodridge because it was too dark. If they had come in shining those lights down there they would have given everybody's position away. When I went to lift Sergeant Woolridge the next morning, my hand went right inside of his leg. It was a funny feeling to know that everything went up in him from the bottom up. He lived for a little while and then died. Four different guys got hit with mines that night. The enemy wasn't shooting at us, our guys were just hitting mines as they were walking. What was surprising was that we didn't have any encounter with the enemy or anything. Just those mines. I can't say that I was mad at the enemy when Sergeant Woolridge stepped on the mine, but I can tell you that I was scared. We were scared because we didn't know who was going to be the next one to step on a mine. A guy named Sandy from our outfit still blames himself. I didn't know he was thinking like that until 46 years later when we saw him at a reunion last year. He said it was his fault that we went through there because the day before he had gone out there with an engineer who had a metal detector and that path was all clear. But it wasn't his fault that they planted mines after they went by. When morning came we could see that they were fresh mines. The holes were fresh because we could see the dirt all loosened up. They had put the mine in and just covered it up. Nobody could see that at night, but in the daytime we could. When the helicopters came in the next morning, we put all the wounded guys on it. They wouldn't take the dead one because there was no room, so we had to carry him back to our line. Gale Miller probably did see movement the night before because we captured a prisoner that next morning and took him back with us. It's been too long to remember, but I think he was a North Korean. We wanted to keep him intact, so we made him carry the front part of the stretcher and we took turns carrying the back part of it. At the time Sergeant Woolridge stepped on the mine, we didn't have a stretcher with us. My assistant was behind me and the last man in the column. He ran back to that outpost by himself and brought a stretcher back. I didn't see one wounded guy or KIA left behind the whole time I was in Korea. The ones I knew were all brought back. 60MM MortarsWe stayed on that hill for a while and then we went in reserve. We stood guard about every third day around Panmunjom, where the peace talks were going on. We were there so that just in case the peace talks broke down there would be someone to help get the brass--the guys at the peace talks--out of there. I don't remember how long that went on. About that time I was told that I was going to be made a Corporal and I would have to give up my BAR, which I didn't want to do. Even though it was heavy, I liked it because it fired faster than the machine gun. Corporals were fire team leaders and they didn't carry the BAR. But I never made Corporal and was never a fire team leader because I got transferred to the 60 millimeter mortars. The 60MM mortars was a mortar section that was right with Howe Company, Third Battalion, Seventh Marines. I was made assistant gunner until he quit. I was the guy that dropped the mortar round in the tube when we got ready to fire it. Being transferred into the mortar section was a blessing in my favor because the mortar section was on the side of the hill. The guys up there on the other side were getting more of the action. The only time we were likely to get it would be if we ever got overrun, which never happened. I was lucky. I had a guardian angel someplace. If I had stayed in the rifle platoon I would have seen a lot more action than I did in the outfit I ended up in. That's why I say it was a blessing. The mortar section I was in never experienced hand-to-hand combat, but had I still been there with the rifle platoon, I would have. Quite a few guys were wounded in the rifle platoon, but we didn't have any wounded in the mortar squad for a long time. The 60mm mortars were not that big, but they helped out the rifle platoons. When a lot of Chinese came up the hill, the rifle platoons called in for us and told us that they needed some help. They told us where they wanted the mortar rounds sent and then the gunner would set the mortars in a little pit. We had already set up aiming stakes ahead of time and our gunner sighted in on the stake so he would know where those rounds were going to go out there. We helped out quite a bit because the mortars were more powerful than the hand grenade. For the most part we stayed right there with the rifle platoon, but once when we were in reserve they called us to go up to Bunker Hill to help a company out that was being overrun. We went up there just for two days and then we went back to regroup after they brought replacements up. I think they were the First Marines. The EnemyIt seemed to me that the enemy was young, about the same age as we Marines. They fought differently than Americans in that they didn't all have rifles. I guess there were too many of them. When one of them got knocked down another one would pick up his rifle. They also blew horns. That scared the heck out of us. They did that for some kind of psychological effect on us--and it worked. When they blew those horns we knew that they were going to come charging up the hill like a herd of cattle coming at us. They had the numbers to fight us. They were dressed in quilted uniforms and wore what looked like canvas sneakers on their feet. We Marines were dressed in regular fatigues and metal, bullet-proof vests and helmets. I carried a bayonet, grenades, and my rifle. One time we went out on a raid and went up a hill to surprise the enemy. But they must have heard us at the last second and they all took off. When we got there we found that they had little fires going and they were cooking their rice or whatever it was. It stunk like heck around there. Our flame throwers came up and just burned the whole hill. Flame throwers shot napalm out from tanks on their back. The tank had a hose on it with a trigger. When they squeezed the trigger flames came out. They burned the whole side of the hill up. They shot at bunkers and burned them up, too. Going back to our lines, the one leading us got lost and went the wrong way. We ended up going in front of another Marine company and they opened up on us. We dove to take cover. Someone must have radioed to them to tell them, "Hey! This is us", because they stopped. The whole deal was scary. We were kind of lost and I was at the tail end of the column. I didn't know if we were running up another hill that the enemy had already taken. When they stopped firing it was a load off of my mind. Sometimes the Chinese or North Koreans played music on a loudspeaker. Then they would say, "Marines, why don't you surrender?" or "Do this/do that." That propaganda stuff was kind of scary because we didn't know what was going to follow. They were threatening us in a way. If we didn't comply with what they wanted, we didn't know if they were going to send a division up our way. FriscoWhen we were in reserve we spent the days digging trenches and things like that. When we went back up on line again we went to the outposts Frisco, Vegas and Reno, where our guys were. I think our guys were mostly at Frisco. The enemy wanted the outposts that we had. It wasn't that they were that high because the highest ground around that area was 229. But they were high hills and they were strategically located. We needed the outposts located on them because they were in front of the line. Without them the enemy could just come right up and march over to us without any resistance. They would take one outpost and we would take it back. They would take one again and we would take it back again. It seemed like it was ruthless sometimes that we did things like that because we lost a lot of men, but we never questioned our orders. We might have talked among ourselves and asked silently, "What the hell are you doing this for?", but when the word came out we just went and did what we were ordered to do. I remember one corporal who was afraid of everything. This was back when I was a PFC and a gunrunner. He should have been a gunner like corporals were supposed to be, but he was afraid to go out on firing missions so they made him an ammo carrier. That was usually a PFC or private's job. He was afraid to do this, afraid to do that. If there were any incoming rounds he would hide. He wasn't a very good ammo carrier either because he was afraid to come out of his hole. But most of the guys were a great bunch of guys and I can't say anything bad about them. I know that I served among heroes. One particular time we started getting a lot of incoming rounds so everybody headed for one big bunker. There was a guy hollering out there that he had gotten hit. One guy jumped out of the bunker and went to get him and bring him in. He got the Bronze Star for that. Accident on 229One night a helicopter with a glass bubble came in to pick up the wounded. It was one of those helicopters with the glass bubble and stretchers on the outside of it. They already had one wounded guy on there and we loaded a stretcher with another wounded Marine on the other side of it and they fastened him down. When that helicopter took off, the rudder turned around, it hit a tree, and the 'copter came down and flipped over on top of the bubble. The pilot and co-pilot both walked out unhurt and one guy on a stretcher wasn't hurt, but the structure of the helicopter went through the other guy's windpipe. He was going, "Hhhaaaahhhh, hhhaaaahh," as we were trying to pull him out from under there, but we couldn't because we saw that thing sticking in his throat. Somehow we got him rolled out of there and laid him on his back. There was no corpsman around at that time, but there was a Catholic priest. The priest took tape and taped him all up and that kid made it. They took him to a hospital ship. I don't know his name, but they said that he made it because they sent another helicopter in right away to get him and the tape held there long enough to get him to the hospital ship. Everyday LifeBeing in Korea wasn't all fighting. Even when we were on the line there were days that nothing happened. Even though bad things could happen, we still tried to make good out of it. We kidded around with everybody. There were things that I did there that I never dreamed of doing. I remember the first bunker we were in after I got to Korea. It was so bad that we completely tore our bunker down and put up one ourselves. I remember we got so tired of the C-rations that we improvised a bit. I kept big orange juice cans, cut the top out, and cooked my meals in there. I mixed up different kinds of C-rations, like mixing ham and limas up with something else. It tasted okay. I guess you could say I kind of became a "gourmet cook" in Korea. We hardly ever got hot meals. When we were in reserve we did, but not up on line. I think that once in a while, if things were going pretty good on the line, they took some of us down to the mess hall to eat, but that wasn't too often. While all the fighting and everything was going on we didn't have a chance to stay clean, although I tried to stay as clean as I could. On Hill 229 we were lucky because there was a stream that came down the side of the hill. At the bottom we dug that stream out deeper and made our own big sandbag-lined bathtub. We took baths in it and a little further down we washed clothes in the stream. That was a blessing because otherwise we wouldn't have had the opportunity to be as clean as we were. We weren't getting showers at all the other places we were. At that spot, we had it made. I'm a Christian. I wasn't real religious, but I started reading the Bible in Korea--not that much, but every little chance I got I read it. I said a lot of prayers, too. There were church services every Sunday on the line and I went every chance I could, but I didn't get to all of them. When I was in reserve I went to church. Funny thing about Korea. We only got to really know the guys in our squad. I knew of guys in the platoon, but not like the guys in my squad. We were in bunkers with maybe three or four guys in a bunker. The bunkers were spread out. In one place I was in one bunker, then way down under the draw there was another bunker, and over there was another bunker. There was so much area in between that all we really got to know were the guys in our own bunker. The only time we got to see the guys in the platoon was when we went out in reserve. Once in reserve there were guys who were going home and then a new bunch would come in. There was always a rotation there, so we really didn't get set with anybody other than the guys in our squad. I saw two USO shows while I was in Korea. I have a picture of a couple of the entertainers, but I don't know who they were. I didn't go on R&R. Every so often just so many guys out of the company got to go, but I was never one that went. I think the longer someone was in Korea the more likely they were picked to go on R&R, but I really don't know if it was based on seniority or what. I never had the opportunity to see how the natives actually lived in Korea. I never went into one of their huts and, in fact, the only natives I saw were what we called "gook trains". The native Koreans carried supplies for us up on the hills. That was the only contact I ever had with them. One time when we were in reserve and we were pulling secondary trench lines, I saw an old peasant woman on the other side of the Imjin River. She was carrying a basket on her head. Where she came from, I don't know. I didn't see any town where I was at. I didn't see any towns at all. I bought a camera off the PX truck in Korea. It cost me $120. The only regret I have is that I didn't have more film. I took quite a few pictures, although I never took a camera out on patrol or anything with me. If I had taken pictures then, I probably wouldn't be here today. But I did take pictures in Korea, and I reminisce all the time now through that. Since the last reunion I've gotten that picture book out at least seven times a week, almost every day. WoundedI was wounded on October 27, 1952. We were in reserve again and there was a company up on the line that was being overrun. In fact, they were overrun. They pulled us out of reserve to go up there to try to get back lost ground. We were getting so many incoming rounds you wouldn't believe it. I think they said at that time that our battalion was setting a record on how many incoming rounds one outfit could take. It was just "boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom" all the time. It scared the cake out of us. We were coming up the draw and they had the mortars dig in the position. We got up there early in the morning and were digging our position while the rest of the guys were hugging the side of the hill in the pass, leaning up against the wall of the hill for as much protection as they could get. Every so often a whole group of them would try to go over the top of that hill in a little valley. None of them made it. They were just getting blown to bits. I was wounded with shrapnel while we were digging in. I had to go back to Medical Battalion for three days. I just figured they would send me back up on line again after they had patched me up. My wound didn't look bad, but I had a hole from shrapnel that went into my finger and came out through the bone. They operated on me in Medical Battalion. All they did was clean the bad meat out of there. I never dreamed that my wound was so serious that I would be leaving the company permanently. The first I knew it was when the doctor who was operating on me said, "I've got good news for you. You're going home." He told me, "Your injury doesn't look bad, but it is." It took me three months to heal up. Like I said, I had a guardian angel when they transferred me over to the mortar platoon. That angel was still there when I got wounded, so I can say I was lucky. If I had stayed in the rifle platoon I could have been killed or wounded like some of the others were. I didn't lose my best buddy, but I lost guys over there who were my buddies and heard about many who were wounded. On the same day that I was wounded, 2Lt. George H. O'Brien Jr., the platoon leader of the rifle platoon that I had been in before being transferred to mortars, was leading the guys through the draw that I talked about earlier. Lieutenant O'Brien's exceptional leadership and heroism that day resulted in a Medal of Honor. He was wounded, but he kept on going. I'm not sure when my parents were notified of my injury. There was a minister at the medical company that took a Polaroid picture of me and gave it to me. He said, "Send this to your parents so you can show them that you're still okay." I wrote them a letter and sent the picture. I don't remember if they got the telegram saying I was wounded before or after they got my letter. I got a Purple Heart for my injury, and it has significant meaning for me. After my operation at the Medical Battalion I was sent to a hospital ship that stayed in the Inchon Harbor in Korea for about ten days. After that the ship went to Japan and dropped us at a naval hospital. Once I realized that I was leaving Korea for good, I was relieved. But on the other hand, I wished that I wasn't going. I had mixed feelings because I had made friends--good friends that I had to leave behind when I was shipped home. How did I just pack up and leave? It was like leaving my family. How do you just get up and go, leaving everything behind--your gear, your own personal belongings, your friends. Of course, the personal belongings didn't mean that much, but there were some things that I wished that I could have taken with me like my camera, pictures and letters. I did get my camera and pictures back, but some of that stuff I didn't get back. I left Korea so quick that I didn't have time to talk to my buddies. Then through the years after I was evacuated from Korea, I lost contact with the guys I served with in Korea. From Japan they flew us home and I had two more operations on my hand at Great Lakes Naval Hospital. My tendons had gone up through my arm and they pulled them back down and put them all together again. It took about 16 months to recover from my injury. When I got discharged I had to report to the VA office. The doctor that checked me there said that I should put in for disability because later on in life if something went wrong with me (rheumatism or something like that), having disability already might help me or affect me somehow. So he put me in for it and I got 10 percent disability. I don't get it anymore because when I turned 65 I had a choice of either paying for insurance every month out of my own pocket or having the VA send a monthly payment to the insurance company, so that's what I did. It's an endowment policy and I get interest on it. When I turned 65 I got a $10,000 check from government insurance that I took out in boot camp and had kept through the years. After KoreaAfter my wounds healed I was sent to another duty station for about 19 months in order to finish up my three-year enlistment. I was discharged from the Marine Corps on September 7, 1954, but then put in five years of inactive reserve. During that time I sometimes dreamed about Korea, but they weren't nightmares. I knew one gunnery sergeant stationed there who would wake up at night screaming like crazy and carrying on. He had been in the Second World War. I never did anything like that. I got married to Veronica Singler in 1957 and worked for a glass company for 42 years before retiring. We have two children, a son and daughter. I haven't told my daughter about my Korean War experiences, but I talked to my son about it after the Marine reunion in Cincinnati. He saw me reading books about Korea and then he read three books that I had and got a couple more. I told him about stepping on the mine and how it happened, but I haven't really told either of my kids how bad it was to sit in Korea and not know if the next round was going to hit me and things like that. I just never thought about getting in a discussion over it. Going to Korea changed me. I don't know if it made me a better person, but I understood war. It made me a person that understood more about life and what other people go through that have hardships and things like that. Being in a war zone is a hardship. Being in Korea also gave me a better appreciation for my own country. I am able to say, "My country. Right or wrong, I'm there for my country." Whether I thought the Korean War or the Vietnam War was right or wrong, if my country had said to me, "You go to Vietnam," I would have gone. There is no sense of patriotism now. I think it starts in the family. No discipline. I think they should never have stopped the draft. They should have kept it going the way it was when I was growing up. I think every guy should go in the service for a couple of years. It doesn't hurt anybody. I mean, nobody likes to go to war, but if there isn't a war I don't see why a guy shouldn't have to go into the military anyway. At least back when I was growing up there was discipline in the family. You got a smack in the butt if you did something wrong and I don't see where that hurts any. Families now don't seem to have that sense of discipline. I remember being in Wal-Mart one time to get some weed killer. I was standing in the checkout line near some young girl who had two little kids with her. The littlest one was sitting in the basket, but the little boy was running around his mother hollering at her. She kept telling him to get over by her and stand there, but he wouldn't do it. We were in the nursery department of the store and this kid stuck his finger in a cactus and got pricked. He was crying and hollering so much that his mother finally paddled his butt. A woman standing behind her said, "You're not supposed to do that anymore." The young mother said, "I don't care what they say. That's my kid. If he does something wrong, he's going to get paddled." What the other woman was actually doing was agreeing with her. She was standing up for her. She told me that she was practicing that with her own kids, too. The same thing is happening in the schools. No discipline. I was a pretty good kid in school and didn't get in trouble, but those that did got disciplined. Nowadays a teacher's hands are tied when it comes to discipline. They can't do anything. I know, because my daughter is a teacher. The last Legion magazine had an article written by an 18-year-old girl who wished that discipline would come back like when the older generation grew up. Tom Brokaw's book, "The Greatest Generation" is a good book. He considered the greatest generation the Second World War generation. I still consider it that. I coached baseball for 28 years after I came back from Korea. I tried to get through to the kids that if they want to do something they need to make up their mind and do it because there's nobody interfering with them now like there was when I was growing up. As I mentioned at the beginning of this memoir, back then all the boys knew that they were going to have to do time in the military. Kids nowadays don't have to do that. They think everything is given to them on a platter and that they don't have to work for it. If a kid wants to go to college he can go and finish his four years without interference. If he wants to pursue a baseball career or whatever, he can do it because there's nothing standing in his way. When I got out of the Marine Corps I was 22 years old already. I lost three years of playing ball. I was done as far as having a baseball career. I don't know if I could have been a Big League ballplayer or not because I didn't get that chance. If I hadn't enlisted I would have been caught up in the draft anyway. It took me 46 years, but I finally found the second guy (Gale Miller) who was hit by the same landmine that killed Woody. I knew Gale got hurt badly and I wanted to try to find out whatever became of him. I didn't know where to look for him since all I knew was that he was from Michigan. At our last company reunion I was checking into a hotel when I came across a Chosin veteran who introduced himself to me. His wife and my wife hit it off good and we got to be good friends. We started talking and he said to me, "Do you know a guy named Gale Miller?" I told him that I had been looking for him for 46 years. That's how we hit it off. He knew somebody I knew. He knew where Gale was at and didn't know his address with him, but he got it from his brother and I called Gale up on the phone. He had had open heart surgery, had a pacemaker, and was now in a nursing home. Before that he had lived at home, but his wife was real bad with heart problems and diabetes so he put himself into the nursing home so she wouldn't have to take care of him anymore. He hadn't been there long when I made contact with him. When I called him, he knew who I was. I then went to see him in person and when I did I stood in the hallway outside of his room because I didn't know whether he was sleeping or not since he was blind and had his eyes closed. I asked the nurse if it was okay to wake him up and he called out to me, "Is that you, Ed?" He didn't see me, but he knew it was me, even though I hadn't told him I was coming. He was really surprised. I went to see him a few times after that, but he died a few years back. Others I have searched for include Bobby Candelario and Hunter Wells. Bobby was from Puerto Rico and Wells was from North or South Carolina. At the Marine reunion in Philadelphia in 1999, I heard that somebody knew Bobby's telephone number. I've talked to other guys that were in Korea with me since that reunion. Our little group gives each reunion attendee a little printout of phone numbers and addresses every once in a while. Final ReflectionsRemember the Gulf War? I was all for what they did and I was for the troops and that, but it seemed like they got a lot more publicity for that short-time war than Korea did. It bothers me that the Gulf War was a week or two weeks long and it got all the write-up and TV coverage that it did, but the Korean War was three years long and it was left behind. I don't like to get into arguments with other veterans, but I almost got into one with another Marine that I once met at a birthday party. He was wearing a Korean War veteran cap and when I was introduced to him I shook his hand and asked him when he was in Korea. He said, "I was there in the Chosin." I told him that I was there in 1952 and he answered, "Oh, the war was over by then." I said to him, "What the hell are you talking about? That war wasn't over until 1953." He didn't say any more. I haven't seen the Korean War monument in Washington DC yet. When I was stationed about 40 miles outside of Washington I saw a lot of monuments in the capitol area, including the Iwo Jima monument, but the Korean War Memorial had not yet been built. When I was in the service I didn't dream of going to see things like that, but when my wife and I got married we went there. Then when my kids started to grow up we took them to DC once. I think the United States went to Korea for a good cause. If we hadn't been there communism might have been spread out farther than what it is. Communism has now kind of fallen off. It's not like before. We stopped communism at the 38th Parallel so it didn't go any further south and didn't go into another country. It was stopped there. I'm happy with what we did there. I think we did our job. I would like to go to Korea on a revisit to see how the country is now compared to when I was there. Back in 1952 it was a mess. The whole countryside was just all tore up. We went through Seoul on trucks when we went from the east coast to the west coast and Seoul was a shambles. There was rubble all over the place and it looked dingy and dreary. Veterans OrganizationsI got involved with the First Marine Division Association last year and I belong to the Disabled American Veterans. I'm a member, but I don't participate. I do participate in the American Legion. I have been First Vice Commander for the last two years and maybe next year I'll be Commander. I also belong to the Brotherhood Association here at the Division. I'm a life member of all four groups. Once Marine, always a Marine. I don't say that the Marine Corps was better than other branches, but we're an elite group. Our discipline made us elite. I'm not knocking the Army or anything, because there are good guys all over. FateI've often thought that if my hand hadn't been where it was, would that piece of shrapnel have hit me some other place? How did that guy get it? How did I miss it? I mean, so many things go through my mind. All I know is if somebody says they were in Korea and weren't scared, they are not being truthful. Everything was happening there. Everybody was scared. I know how my buddies were and I know how I was. We all looked out for each other. When I came back from Korea I went to a New Year's Eve party at a big dance hall with my buddies from home. Some guy who had been in World War II met me on the outside and he started in on me about the Korean War. I don't remember all that was said, but it really stuck in my mind that somebody would be against me because I was in the Korean War. That's like the guys in the Vietnam War. Look at how many people were against them. I don't feel that way. I can't understand why anybody that was in any war would feel that way towards the other guy that went after him if he's in a different war. You would think that you would have the backing by these guys at least, because they went through the same thing. I've often said to other people that I am not sure the people of the United States will pull together like they did during the Second World War if our country gets in a big war again. I was nine years old when World War II started in 1941. It seemed like the whole country came together and did what they had to do to win the war. There's going to have to be a drastic change in the way people think in order for them to come together like that again. Draft dodgers bother me. I can see why they wouldn't want to go to war, but I also see that we should be for our country because if our people before us hadn't done what they did, we wouldn't have what we have now. This goes right back to the Civil War or any war. Whether it was the First World War, Second World War, or Korean War, they all have their own little story. My personal contribution to the Korean War was myself--giving up three years of my life to be in the Marine Corps. I was only in Korea about eight and a half months, but it was eight months of my life for another country. In one way I am resentful because I couldn't pursue the career I wanted, but in another way I'm not because I got in the branch of service that I wanted to be in. I might not have been a ballplayer anyway. But I'm not ashamed to tell people that I was in the Korean War. Like I said, I think what we did there had to be done, and we did it, whether we get credit for what we did or not. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||