|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||

|

|

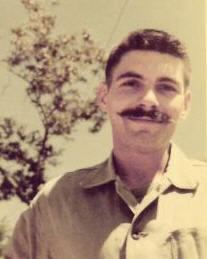

John (Jack) ParchenSan Jose, California "I was impressed by the thoroughly professional--almost stoic--attitude of the enlisted Marines. They were not fighting for 'mom and apple pie', but because they were in Korea to do a job. The men had a 12-month tour of duty. Even allowing for time in reserve, that meant about 8 months on the line, and in possible combat. With a casualty rate of 5% or more per month, that meant that a man in a rifle platoon had a nearly 50% chance of being killed or wounded during his tour. There was very little of the rah-rah or 'gung ho' about the way they went about their work, but a quiet acceptance of the need to do a job, and do it well." - John (Jack) Parchen

|

||||||||||||||

Memoir Contents:

Pre-MilitaryMy name is John (Jack) Parchen and I was born 22 January 1929, in Providence Hospital, Seattle, Washington. My family lived in Cle Elum, Washington, at the time. Cle Elum was then a coal mining town of about 2,100 people, one hundred miles east of Seattle, across Snoqualmie Pass, at the upper end of the Yakima Valley. My mother did not trust the medical care available in the four-bed miners’ hospital, and opted for Seattle for my birth and that of my younger sister. I am the son of John Edwin and Emma Lucia Morgando Parchen. My father owned a hardware and furniture store in Cle Elum, Washington, from 1923 until he sold it in 1940 so we could move to the Puget Sound area. But all of his life he considered himself a "small businessman." He owned and operated a small hardwood panel plant in Auburn, Washington, from 1940 until 1942, when labor shortages caused by the draft and the higher pay in the Tacoma shipyards, forced him to shut it down and later sell it. During World War II, he worked for the Office of Price Administration (OPA) and then evolved through several other government agencies until he was employed in various executive positions in the Small Business Administration. He worked for that agency until his death in 1964. My mother was a housewife who took care of the house and our family of four. I have one sister, who is 3 1/2 years younger than I am. I attended the Cle Elum, Washington, grade school through the fifth grade; attended the sixth grade in the Ballard District of Seattle, Washington; attended 7th through 12th grades in Auburn, Washington. I graduated from high school in June, 1947. I can provide details because throughout my junior and senior high school years, and until I went off to college in the fall of 1947, I kept a daily "journal" of my activities. My first real job began in the summer of 1941, when I worked for my father in his hardwood panel plant. My work was partly janitorial sweeping and shoveling sawdust and wood residue from the manufacturing process and partly handyman -- providing another pair of hands for any job that needed to be done, e.g., helping stack or unstack pallets of hardwood panels. My pay was 12 1/2 cents per hour. I continued this work during school vacations and on Saturdays during the school year. In the summer of 1942, I negotiated a salary increase to 20 cents per hour, but the plant was closed before August. In the summer of 1942, I began delivering a once-per-week free advertising "shopper" paper; the pay for my route (about 1/3 of the town) was about 50 cents. That fall, I began working a few hours on Thursday of every week, which was "press day," for one of the town’s two weekly newspapers. I would then make deliveries of the paper. My records indicate that I was paid 25 cents for delivering the papers, and 30 cents per hour for the other work. On January 1, 1943, I began delivering a morning paper route of the Seattle POST-INTELLIGENCER. Over the next few years, I worked up to becoming the "head carrier," which meant that I had the downtown route, but also was responsible for finding boys to be paper carriers, and finding replacements when they quit or were fired. I frequently had to carry two or sometimes three routes myself (usually in the summer months) until I could find an adequate replacement. I continued delivering the "Seattle P.I." until the month before I graduated from high school. During the three summers I worked for the U. S. Geological Survey (described below), my sister would take the paper route, or I would find a substitute. My income from my first few months of delivering papers was about $20 per month. On the few occasions when I had to deliver three routes, the income reached $50 per month. The income was one of the good parts; the other good part was that while I was in high school, my after-school hours were free to participate in sports and other school activities. The bad parts were: (a) getting up very early in the morning, seven days a week -- all papers had to be delivered by 6:30 AM, rain, snow, or whatever -- and I was always short of sleep throughout high school; and, (b) collecting from each customer, or trying to collect from each customer, every month. This was absolutely necessary because the newspaper sold the papers to me, and what I collected was my profit -- or, loss, if I could not collect. Collecting for the newspapers took five to eight evenings each month; when I had more than one route, I frequently hired my sister to help me collect. All of the paper routes were covered by bicycle; besides inclement weather, the major scourge of pedaling papers was flat tires -- and these were very frequent due to the poor quality of synthetic rubber available for inner tubes. In April 1943, I was hired as a "printers’ apprentice" by the owner of the AUBURN GLOBE NEWS, by then the town’s only weekly newspaper and print shop. I worked after school on Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and either a half-day or a full day on Saturday. My pay was 35 cents per hour. One had to be 16 years of age to be an official printers’ apprentice and be so recognized by the Typographers’ Union, but I was allowed to do odd jobs (and more) in this strictly unionized shop because it was not possible to hire someone at or near draft age at that time. When school let out in June, I was able to work more than my usual 12 to 14 hours per week; my hours went up to 20 to 25 hours per week, and my salary was increased to 50 cents per hour. When junior high school resumed in the fall, my work schedule went back to 12 to 14 hours per week, and I continued on that basis until the summer of 1944. At that time, my hands and arms broke out in a severe rash, apparently as a reaction to the cleaning fluid used to clean type. I had to give up my occupation as a "printers’ devil" -- but just in time to turn out for the high school football team. My work during this interesting time in my life gradually increased from helping with the press run and other odd jobs such as melting down the lead to reuse in the linotype machines each week, to helping set and later break down hand-set type, and casting and balancing the mats used for photos and ads. In the spring of 1945, the U. S. Geological Survey was looking for young men below draft age to accompany engineers on field trips during the summer. Four of us from Auburn High School were hired, although I was the only one to return for a second and third summer’s work. The USGS, Water Resources Branch, headquartered in Tacoma, was responsible for gauging the rivers and streams in the state of Washington on a regular basis, and developing tables and graphs to indicate historic patterns of water flow, to be used in projecting or forecasting how much water was available for power generation and agriculture -- or how much flood control would be needed. For the first two summers, I helped engineers in the actual "stream gauging" -- the first river that I helped gauge was the Columbia River, near the Canadian border. Of course, I also did routine maintenance of the gauging stations, including cutting brush, bailing accumulated mud out of the "wells," and painting. The pay was about $110 per month, plus $4.00 per day for expenses when in the field. During my first two years, I was in the field and away from home for stretches of two to three weeks at a time. By my third year, the returning veterans had replaced those of us helping engineers gauging streams, but I was hired as a construction worker. The pay was better ($141 per month plus $4.50 per day for expenses when we were in the field), but the work was much harder and not nearly as interesting as the stream gauging. During my three summers with the USGS, I worked on rivers and streams in the mountains and foothills in every part of the state of Washington. I went on one snow survey with the Geological Survey. Late in February, 1947, I was offered the chance to go on a snow survey that might last as long as eight days -- if I could get excused from school. The pay was $12 per day. Two engineers had been injured on recent snow surveys, and they needed someone who could ski to help an engineer. I got excused from school, went to Seattle for a very thorough physical exam and two interviews for the NROTC program on Tuesday, and left on the snow survey on Wednesday morning. We had generally good weather and completed our work on Mt. St. Helens and Mt. Adams by late Sunday, and managed to get back to Tacoma by 9:00 PM. The following morning, Monday, I had to return to Seattle to have another x-ray taken for the NROTC physical exam, and the next day was back in school -- in time to try out for the Senior Class play -- and begin studying to catch up with the five days of school work that I had missed. If I have given the impression that I was very busy during my junior and senior high school years, that is correct. I always had one or more jobs. I had only two "vacations" during this time: (a) a period of 56 days in 1946 when the Seattle P.I. was shut down by a strike, and I had no newspapers to deliver; and, (b) from May 1, 1947, when I finally gave up the paper routes until I started my summer’s work with the USGS on June 9th. Throughout my high school years, I paid for all my own clothes, bought ski equipment, books, and a good camera, and paid my own expenses for dating, skiing, and other activities. By the time I left for college, I had $2000 savings in savings bonds. While I was in high school, the morning paper route was important because it left my after-class and weekend hours free for other activities. I was on the football team; I was a good linebacker--which helped to compensate for my light-weight 148 pounds--and played first team in my junior and senior years. I went out for track two years--just to stay in shape for football–-but was too slow at even the mile to do better than place third in a few meets. Skiing in the winter was a favorite sport, and most weekends friends and I would take day trips by auto to Mt. Rainier or Snoqualmie Pass, or would catch the Milwaukee Railroad’s "Ski Train," leaving at 7:00 AM and returning about 7:00 PM, for a full day of skiing at the Milwaukee Bowl in the Cascades. Weekends in the summer meant swimming and parties at the local lakes, two of which also had dance halls and bands. There were many other school activities. I was elected Student Body President of the junior high school, was President of the Sophomore Class, and Vice President of the Student Body when a senior. I was an active member of the drama club: I authored the class one-act play (a farce about an old-fashioned Christmas) in my junior year; had the male lead in the all-school play in my junior year, and in the senior play the following year. I was co-chairman of the Senior Ball committee, an activity that was notable only because we had a small battle with the Principal and the class advisor over the theme and decorations, and felt we scored a victory with a very successful dance. The announcement that I was Valedictorian of my high school class came on the same day that I learned I had been selected to attend Stanford University on the NROTC program. I joined the Boy Scouts in Auburn, Washington, when I was 12 years old. However, my father had started taking me with him on four- to five-day deer hunting trips when I was seven years old (in the second grade). Those trips, plus numerous fishing trips and "deer scouting" expeditions into the mountains each summer while I was in grade school, meant that I had much more experience in the outdoors than most others in the scout troop. I went on several scouting overnight hikes, but did not find them to be very interesting -- except in watching the ineptitude of some of the others. I earned three or four merit badges, but grew weary of weekly meetings and knot-tying sessions. Several of us looked forward to reaching age 14 when we could join the Sea Scouts. That organization had a small boat moored nearby on Puget Sound; furthermore, we would then be eligible to buy seamen’s pea jackets. Then WW II began, the Coast Guard requisitioned the Sea Scout boat, and the organization disbanded. No one in my family served in the Armed Forces during the war. My father had served a little over a year in the Army during WW I. During WW II, he "volunteered" for any position in the Office of Price Administration, and was employed in the office in Seattle. A year later, he was offered a promotion to be Regional Trade Relations Officer in San Francisco; he accepted and, until the summer of 1944, lived in an apartment in that city. He was able to visit the family in Auburn, Washington, only when he made business trips to the office in Seattle. He was called back to Washington, D.C., on several occasions to help prepare manuals on procedures for price controls. However, I do not mean to suggest that his employment with the OPA equated with service in the Armed Forces. It goes without saying that our family made the same war support efforts that all other civilians did: we faithfully followed the rules on the rationing of meat, butter, gasoline, and other products; collected tins cans as long as that drive was encouraged; and, turned two flower beds into "victory gardens," planted with tomatoes, beans, carrots, onions, and radishes. In junior high school, we had an all-school assembly each month during which a speaker (usually someone in uniform) would encourage the students to do their part by buying 25 cent savings stamps, and then trading the filled savings stamp booklets in for $18.75 saving bonds. I believe that I bought a savings bond each month since I was well employed. In the fall of 1943, I was elected Student Body President of the junior high school. That meant that I presided over the savings bond rallies. Further, I noted in my journal that I took charge of the Armistice Day Program and " .. introduced Army officers, including a Colonel -- and thanked them." Joining UpMy parents saved all of the letters that I wrote during college and NROTC summer training -- in fact, they saved all of my letters until I married. During the college years and summer training, I wrote home about once each week. I wrote often because it was expected of me. While in college, I got a long distance telephone call from my mother if my parents hadn't heard from me for ten days. I also observed all birthdays and Mother's Days and Father's Days with cards. Because of this, I have a fairly complete record of my activities during those years. During the past year I have written about my college years and the NROTC summer training. It will be a long appendix to the "family history" work that I am still doing on my parents and our family life. I had not, however, previously thought about the question: "What were your educational goals at the time?" In my family, it was a given that my sister and I would attend college, and graduate from college. My father had one year of college and one of his sisters had two years of "normal school" so that she could become a school teacher. His other six siblings either married young or went to work in my grandfather's store. My mother left school after the eighth grade. Her brother went to work in the coal mines probably before finishing the eighth grade. Nevertheless, despite this dearth of education in the generation of my parents, academics and academic progress was seriously stressed in my family and the families of my cousins. In my case, I was seriously berated over the one "C" grade I received in high school, and was criticized over receiving a rare "B." Of my thirteen cousins, nine graduated from college, and three of those have advanced degrees. Both my sister and I graduated from college. That makes a total of eleven college graduates out of fifteen in my generation, and should offer proof that higher education was stressed. I had two goals at that time: to attend college and to get away from home. I planned to major in engineering or geology. Although it seems strange to me in retrospect, I never once gave a thought to graduate level education; my father only wanted me to finish college (and, later, my service commitment) and then return home so that he could, with my help, start up and again run a hardware store. I was almost certainly headed for the University of Washington in Seattle. One of my older cousins had a brilliant career there, and was constantly held up to me as a role model. Further, I knew several older fellows from Auburn High School attending the U. of W. and my older cousin, all of whom were waiting for me to choose between their fraternities. Although the term wasn't used then, I came from a very dysfunctional family. My father and mother were totally incompatible, and should never have married--or stayed married. My father was intelligent, quiet, and hard-working. He was also "hard of hearing" and suffered from frequent migraine headaches. My mother was bright, generous, and could be warm and affectionate toward me and my friends--but not to my father. She was also very neurotic, and could be extremely harsh and abusive in speech. Our family life was marked by very frequent, angry arguments and long periods of sullen silence. While in high school, I got away from home as much as possible. My sister would simply retreat into her room and shut the door. I could relate how in later years my mother slipped deeper into paranoia, and how her "affectionate" side disappeared, but the above should explain why I wanted to get away from home. If I was accepted in the NROTC program, my two educational goals would be immediately satisfied -- attending a very good university (for which my parents almost certainly would not have provided financial support), and getting far away from home. I joined under the Holloway Plan. Although I knew very well what the commitments were (mine and the military's), I was unsure who Holloway was. I queried several Marine Corps friends that I knew had been in the program. The definitive answer came from LGen Bernard (Mick) Trainor, USMC (Ret.) I will quote his e-mail:

The NROTC program provided:

The NROTC program required:

In my case, the advantages of NROTC were obvious: (a) although the tuition at Stanford was only $175 per quarter when I was a freshman, increasing to $250 per quarter when I was a senior, my parents would not have supported that amount; (b) to attend a prestigious university (no one from my high school had ever attended Stanford); and, (c) to get far away from home. There were several disadvantages to the program that we became aware of during the college years or after being commissioned:

There were 48 first year students in the NROTC program at Stanford at the beginning of the year, although 5 had been dropped by the end of the year for academic or physical reasons. A Navy Captain was the Professor of Naval Science and headed the unit; the Marine instructor was a Major. Those of us at Stanford soon learned that all of us had requested Stanford as our first choice university. During the first summer cruise we were able to deduce from students from other colleges how the selection process worked. A fellow I met on the cruise had been enlisted on active duty in the Marine Corps when he applied for and was accepted into the NROTC program. He was offered schooling at Miami of Ohio; not only had that university not been on his list of choices, he had never even heard of it -- but he accepted because it was that or nothing. None of the NROTC students attending the University of Idaho had requested that college as first or second choice. It was apparent that our assignments to a university were based on our ranking in the competitive exam. My father was very pleased when I accepted the NROTC offer for two reasons: the financial support that would have to be provided for my college was reduced a great deal; and, he had attended Stanford for one year after getting out of the Army after World War I but ran out of money and returned to Grandview, Washington, to work in his father’s store. My mother was very pleased (and proud) that I was going to a fine university. Further, one of her favorites nieces (twelve years older than I) was married to a graduate of the Naval Academy, and she had always admired him and his "fine life" as a Naval officer. NROTC ClassesStanford graded on a strict bell curve (this was long before the gradeflation that occurred at all colleges during the Vietnam War), and the average grade was supposed to be a C, with as many D and F grades as B and A grades. Actually, of course, the average grade was about C+. A student who fell below C average for two consecutive quarters was suspended. (The President of the Freshman men flunked out during the Winter Quarter, and had to be replaced.) I was the Valedictorian of my high school class, but I wrote home during the Fall Quarter that I had done more studying and homework in the previous month than I had during the total of my high school years. The entering freshman class in 1947 numbered between 1100 and 1200 students; the men outnumbered the women 3 to 1. All Stanford undergraduate students were required to live in university housing unless their home was within a short radius of the campus or they were married. All freshmen men lived in a single dorm, Encina Hall, and all freshmen women lived in Roble Hall, on the opposite corner of the campus from Encina. Stanford had abolished sororities in the early-1940’s and the university had taken over the sorority houses to use as women’s residences. Those former sorority houses plus several women’s dorms and residences were sufficient to house all of the women students. During the Spring Quarter, the freshmen women drew lots and then chose the residence each preferred. The situation for male students was different. There were 24 fraternities, each with about 40 to 45 residents. Fraternity "rush" was during the Winter Quarter. Since there was then only one residence hall for undergraduate men who did not pledge a fraternity, the many for whom there was no space had to live in "Stanford Village," a former VA hospital located about 4 miles from campus in Menlo Park. There, men occupied two-man cubicles in long wings -- much like a barracks -- and ate in a common mess hall. (This was not a satisfactory situation!) Freshman Year -- 1947-48All Stanford students had certain course requirements to fulfill in order to progress from Lower Division to Upper Division, and to a degree.

Additionally, in my freshman year I took two quarters of Analytical Geometry and one quarter of Calculus. My Naval Science courses were two quarters of "Introduction" and one quarter of Navigation. I remember the "Introduction" courses as being mostly naval terminology and customs, plus the phonetic alphabet, Morse code, and the meanings of the Navy pennants. The Navigation course covered such basics as latitude and longitude, charts, and rules of the road. All in all, the Naval Science courses were easier than the other courses I was taking, and required less homework. There was one other period of Navy "indoctrination" during the year. Thirty-eight midshipmen took the opportunity for a one-day cruise on a submarine. We boarded SSN Sea Devil, a fleet-type diesel boat, at Treasure Island, and sailed out through the Golden Gate on the surface before submerging about ten miles out at sea. The surface trip once we passed the Golden Gate was the roughest ride I have ever experienced on any ship at any time; many of the boat’s crew and almost all of the midshipmen were very seasick -- until we submerged and the ride smoothed out. Not many of the Middies took advantage of the excellent lunch served that day. Fortunately, the ride on the surface back to Treasure Island was much smoother. My course load was 15 units in the Fall Quarter, and 16 units in the Winter and Spring quarters. Despite getting two C grades in the math courses, I finished the year with a B+ average (3.23 grade point). NROTC Summer Cruise - 1948The Naval Academy and some other Eastern colleges that finished the school year by the first of June made a European cruise on cruisers. The rest of us -- numbering about 1800 -- boarded the battleship Iowa for a Pacific cruise. The Iowa had a wartime complement of over 3000 men but by 1948 the crew numbered about 1750, which created enough room to crowd in the midshipmen. I was in a division of 52 midshipmen, crowded into a compartment measuring 36 by 25 feet. We each had a half-locker, and our bunks were in tiers of three or four racks. Our compartment was above the Number 2 boiler; when the ship was steaming, the steel deck of our compartment became hot to the touch. Further, the compartment was located one compartment aft and one deck below the Officers’ Wardroom. After reveille, while policing the compartment, we could frequently detect the delicious odors of bacon and eggs wafting down from the Wardroom. We would then make our way aft, to line up with our aluminum trays at the Enlisted General Mess -- to receive our breakfast of baked beans and a hard-boiled egg, or soggy so-called French toast and powdered scrambled eggs. We had a schedule of section watches totaling eight hours every other day, with classes and such tasks as

swabbing the decks, or polishing brass and metal work topside, or gun drill, on the alternate days. The classes

were not held in a wardroom or other quiet space, but consisted of a group of us standing around a petty officer

while he tried to explain the workings of something like a compressor or a refrigeration unit. On our first morning sailing out of Pearl Harbor, the Iowa participated in sinking the battleship Nevada. The Nevada had been the target ship at the Bikini A-bomb tests, and was pretty much of a hulk. Planes from four airfields on Oahu had been using the ship for target practice for two days, without doing any critical damage. At a distance of about ten miles, the Iowa fired 18 rounds from the 16-inch guns, and scored only one hit, but had the Nevada bracketed when they ceased fire. The cruisers moved in and fired 8-inch and 5-inch guns, and at a distance of about five miles, the Iowa then worked her over with 5-inch guns -- but the Nevada showed no signs of sinking. We were all on deck as the Iowa moved close enough so that we could see Navy and Marine Corps planes firing rockets at the Nevada. Then Navy torpedo planes put five or six torpedoes into the side of the old ship, she slowly rolled over, and slid under the waves, stern first. The Iowa remained in Long Beach while we spent a week at the Coronado Amphibious Training Base. Our amphibious training ended with a full day of landings, assault, and battle/beach construction demonstrations. Thirty-five midshipmen were allowed to ride in the assault wave during the landing; I managed to wheedle my way into the first wave, with about 20 Marines in an LVT (Landing Vehicle Tracked). I suppose the principal reason for wanting to be in the "assault wave" was that it would be more interesting and exciting to land in an armored assault craft (amtrac) than from the standard landing craft--and it was. I am not sure I learned much from the experience, but it was good to travel and land with a mixture of Marines and midshipmen rather than a gaggle of partly-seasick midshipmen. After our return to Long Beach, the Iowa put to sea for four solid days of gunnery practice. Off and around San Clemente Island we had endless gun drills and then live firing. The 16- inch and 5-inch guns blasted the island. I had been assigned to a quad-40 mm. gun mount during the entire cruise, and we finally were allowed live firing at drones. That ended our summer on the Iowa, and we were on our way home after anchoring in San Francisco. If the Navy wanted to show midshipmen how an unrated seaman lived and worked on a large ship, they certainly succeeded. The "classes" on board ship were largely wasted time, and most of the watches we stood were mind-numbingly boring. (Especially memorable was the midwatch -- that is, 11:45 PM to 0345 AM -- in the after shaft alley, seven decks down from the main deck. The watch consisted of keeping an eye on oil pressure gauges on two or three large bearings that bore one of the ship’s 37-inch propeller shafts. The steady murmur and the rotation of the shaft was hypnotic; one was not allowed to read or do anything else except try to keep awake.) The liberty in Hawaii was pleasant, particularly because my ex-Marine friend met a Chinese-American girl at the Governor’s Ball held on the quarterdeck of the Iowa on our first evening in port, and she had a sister. The amphibious training at Coronado was well done, and watching or participating in live firing exercises was always interesting. Sophomore Year -- 1948-49The courses in my second year of college began to move toward my major of Geology.

During the Winter Quarter, I was swamped with school work, and did not attend enough tennis classes to complete the requirement. The NROTC unit had a rifle and pistol team; sometime during the year, it had been granted status as a P.E. course. I took that "course" during the Spring Quarter, and rather swiftly made the team. We competed in matches against NROTC units at other California universities. During the Fall Quarter, my school schedule was complicated by the fact that I had three hours of lab work, three days per week (Machine Drawing and Physics lab). The courses I was taking, and my trouble with Calculus, meant I had very little time for anything besides schoolwork and homework. For my 46 quarter hours of credit during the year, I managed a B- average (2.71) despite the three D grades in Calculus. For my two years of college, I had dropped to just below a B average (2.98 GPA). Marine Corps OptionDuring the Spring Quarter, I requested a change from the Navy program to the Marine Corps. The NROTC unit had a maximum quota of seven students for the Marine Corps. My memory is that the seven who requested the change and were accepted were among the top eight students in the unit. I was accepted by the Professor of Naval Science and the Marine Corps instructor before the quarter ended, and told the next step would be acceptance by the Department of Navy. We were informed of our acceptance when school recommenced the next fall. The reasons for my requesting the Marine Corps included the following:

There were several instances that contributed to my feelings about the Marine Corps. I lived on the West Coast, and we followed the war in the Pacific much more closely than the conflict in Africa and Europe. I had a map tacked to the wall in my bedroom, read the newspapers every day and LIFE magazine every week, and kept close track of the battles in the Pacific--which, of course, were largely Navy and Marine Corps actions. For several years, and until we moved from Cle Elum, Washington, to the Puget Sound area, I was a member of the "Junior American Legion Drum and Bugle Corps." (I attained the "high rank" of Corporal of the drums.) Our drill master was a young man, about 18 years of age, named Doug Monroe. He enlisted in the U.S. Coast Guard before Pearl Harbor. He was the coxswain of a landing craft at Guadalcanal/Tulagi, and was killed while deliberately running his boat between the Japanese firing machine guns from shore and the landing Marines in order to protect the Marines. He was awarded the Medal of Honor--the only member of the Coast Guard to receive that award. His mother was past the age for military service, but received a waiver and served as a WAVE officer for the duration of the war. We knew the family well from our days in Cle Elum. Additionally, I formed an opinion about the Marine Corps when I bought a paperback copy of "Guadalcanal Diary" by John Hershey. It made a strong impression on me. And I suppose, there were the John Wayne and other wartime movies. I have already written about the very favorable impression that the Marine Corps officers made on many of us during our NROTC summer training sessions. Meanwhile, I had declined an invitation to join one fraternity during my freshman year, waiting for and expecting to receive an invitation from one that I much preferred. That offer to join was not offered, and I lived in Stanford Village during my second year of college. During the spring, however, I was invited to join Theta Xi fraternity and accepted. I moved into the fraternity house when school started in 1949. My parents (principally my father) had finally relented and released enough of my savings to buy an automobile -- a 1946 Chevrolet. The car not only made it much easier to commute to and from Stanford Village to the campus, but provided the means to go on an occasional ski trip and participate in other social activities. My financial support from home was $175 per quarter -- which was almost exactly the cost of my board and room. That meant that I had the $50 per month from the Navy -- plus whatever I had earned and saved from working after the summer training session -- for all other expenses. Those other expenses were not just for social activities and gasoline, but included: the weekly 50 cent haircut that the NROTC required; Sunday evening dinner, since none of the university residences provided that; doing laundry; school and correspondence supplies; necessary auto repair or maintenance items; cigarettes and an occasional snack; and, the cost of my travel (usually a 24-hour bus trip) to and from home during the vacation breaks. Further, before the summer cruise on the Iowa, I had to spend $35 at Moffett Field for the regulation underclothing, socks, and uniform items that I would need during the cruise. During my freshman year, I supplemented my "income" by playing poker in games in the lounge of the dorm. I had been playing nickel-dime poker with friends since junior high school. Many of the freshmen considered learning to play poker a part of their college education -- but, like any education, it could cost money. A good evenings winnings was $4 or $5; a big evening was winning $10. In one letter, I wrote that I had won back the $13.50 that I had lost the night before. In my second year, however, the heavy schedule of lab work and other homework meant that I had hardly any time for poker, and my finances were strained by the end of each month. I had to roll my own cigarettes, but was willing to do that to compensate for the extra costs incurred by the automobile. My parents did not play cards of any kind--not poker, bridge, or even gin rummy. While I was in high school, they probably considered--as I did--that poker was more recreation than "gambling." I don't remember ever being given a "hard time" for playing poker unless the game ran too late. Perhaps my parents felt that a poker game was a less harmful activity than others that could tempt teenagers. At least, we always played in somebody's home, and were, therefore, under some sort of loose supervision. While in college and in the service, I played poker more seriously, and studied and worked hard at it. However, I never played in a game with people that I didn't know at least casually. My wife and I don't go to Las Vegas, Reno, or Indian casinos. We don't play slot machines or buy lottery tickets. The last time I played blackjack (or "21") was almost 50 years ago--when I learned that it was not "gambling" because the dealer, over time, will always win. I haven't played in a poker game in over 20 years, but I still have a well-thumbed copy of "Oswald Jacoby on Poker" on my bookshelf and a poker game on my computer. The only gambling that we do now is buying $2 or $5 tickets on a horse race on our twice-yearly trips to a local race track. NROTC Summer Training -- 1949All NROTC and Naval Academy students had the same summer training schedule -- two weeks of Marine Corps training at the Amphibious Training Center in Little Creek, Virginia, and six weeks at the aviation facilities in and around Pensacola, Florida. The people going to summer training were split into two groups, with different schedules; our group was scheduled first for Little Creek and then Pensacola. My Travel Request (TR) from the Navy provided for train travel from Seattle to Baltimore and then overnight packet boat to Norfolk; after Pensacola, the TR was for train travel to Seattle via New Orleans and Los Angeles. I left Seattle early enough to stop in Chicago and spend several days visiting at the home of a friend from college. (As the mother of my friend, Mrs. Fox, was saying goodbye to me, she said something to me in Hebrew or Yiddish. It was then that she learned that what I had at the end of the chain around my neck was a St. Christopher medal and not a capsule containing something from the Torah.) I wrote home that the training at Little Creek was well-planned, interesting, and decidedly worth-while. The first week was all lectures in the morning, and tours and practical training in the afternoon. The second week included four days on a troop transport for actual amphibious operations. I had been told at college before the Spring Quarter ended that I was one of five midshipmen from five different colleges that had been selected as midshipmen regimental officers while at Little Creek. I was to be the Regimental Operations Officer, the third ranking in the regiment, with a midshipmen ranking of Lieutenant Commander. At Little Creek, however, we learned that there would be no regiment, only companies -- so I had a non-existent job. We were billeted 12 to a Quonset hut. The base was so large that using the recreational facilities was difficult -- for example, it was a 2-1/2 mile walk to the Officers’ Beach. The weather was very hot and humid; I wrote that, "By actual timed test, it takes a clean khaki shirt just 55 seconds to wilt and dampen in the heat." One of the complaints of the middies was that they had not been paid by the end of the first week, and many were too broke to go on liberty. I never did go on liberty but stayed on base and played poker, with more success after we all were paid. We traveled to Pensacola by a Southern Railroad troop train. It was a hot, dreary trip; the train was soon more than six hours behind schedule. The main base at Pensacola made a good impression: "Mostly brick buildings -- all air conditioned -- and, in general, very pretty." The base had everything one needed: a fine theater, beaches, a cadet club (beer only), and a large library. We were on tropical hours: reveille at 0430, with liberty from 1500 to 2230 on weekdays, and until midnight on Saturday, with all day Sunday off. Our schedule called for three weeks at the Main Base, followed by a week on the USS Cabot, a week at Saufley Field, and a final week back at the Main Base again. We were billeted four to a room in an old, very hot, wooden barracks. The first step in the morning was to go to the vending machines in the corridor to get a bottle of Dr. Pepper or a cup of fruit juice to counter the dehydration that came from sleeping in the stifling room. The next task was to make up our racks, polish the chrome on the room’s sink, and then sweep out the piles of cockroaches that had been killed during the previous day and night. Our chow was in the Officers’ Candidate Mess, and was very good -- including all the milk that we wanted. Breakfast was followed immediately by marching -- at 0600 hours -- to an air conditioned theater for several hours of training films. Some of the films were interesting (e.g., dive bombing, weather fronts, etc.) and some were incredibly boring (e.g., navigation, venereal disease, etc.) Many found it almost impossible to stay awake during the films. Some of our Middies were very systematic about the process, and carried newspapers in to the auditorium -- to spread on the floor between the rows of seats to keep their white uniforms clean while they stretched out there to sleep. The films were followed by classes until 1000 or 1100, then two more hours of classes and an hour of P.E. at the Officers’ Beach before 1500. I enjoyed the skeet shooting (for gunnery practice) and classes on the principles of flight. We had quickly learned that we would be handled strictly. The Naval Air Cadets were treated the same as the Academy midshipmen, and we were to be treated like the Cadets, including room inspections every day, extremely rigid rules for saluting, numerous musters, and extra duty marching for demerits, etc. My week as Platoon Leader had several close calls on demerits involving my platoon’s cleaning details duties. Most of us considered the week spent aboard the USS Cabot as the worst week of training in any of our three summers. The Cabot was a small aircraft carrier operating in the Gulf for carrier qualifications of student pilots. We boarded on a Saturday morning and were immediately given two hours of "indoctrination" warnings by the officers in charge of us -- composed of "do’s" and "don’ts" of all varieties. We were warned that the Captain was a real killer, and the Executive Officer hated midshipmen. On top of that, the tempers of the officers and crew on board had worn thin during the previous ten weeks of groups of Middies committing the same blunders, getting underfoot, crowding facilities, etc. And after five weeks of comparative comfort, the midshipmen were none too happy about being jammed back into small crew compartments, chow in the E.M. mess hall (not good), and generally pushed from one end of the ship to the other. Further, we soon learned (from petty officers, among others) that morale on the ship was very low -- and all of them hated the Captain. Each day we had lectures and observed flight operations on the flight deck. Then, because the Captain felt we ought to do "something constructive," we would chip paint for more than an hour every day. I particularly remember the paint chipping details on the hangar deck every afternoon. With our dungaree shirts buttoned to the collar and to the wrist, we hammered away with our L-shaped "chisels" in the stifling heat of that deck. Why the midshipmen, as well as members of the crew, had been chipping paint on that tub is an interesting (and true) story, as related below. Watching flight operations, and enjoying the scenery of the Gulf, with porpoises and flying fish, was very good but did not make up for the rest of the irritations of the week. I will quote, in part, from my letter home:

I should add that other midshipmen heard almost identical versions of what I have related above. I believe that the Cabot was recommissioned from the Philadelphia Navy Yard. The following week, at NAAS Saufley, was the best of the summer. Saufley was a training field, about 10 miles from Pensacola, where the cadets trained in gunnery and fighter-tactics. We had good chow, a good pool, and lots of spare time. I was fortunate enough to get in a cross-country training flight that took us to New Orleans. I flew in the back cockpit as "navigator" for a Cadet pilot; an instructor led our flight of five planes. The "easy" time at Saufley turned out to be profitable for me also. Before the summer began I had decided to keep careful track of my winnings and losses at poker, with the objective of winning enough to buy four new tires for my Chevrolet. The $18 that I won at Saufley took me up to total winnings of $88 for the summer -- just about the amount needed for the tires. Of course, the poker also let me save money by keeping me out of the Cadet Club or liberty trips into town. Our final week at Pensacola was spent back at Mainside. It was mostly practical work and tests. However, it

also included a two-hour flight in a PBM seaplane. The flight gave us the opportunity to observe cockpit

operations, and each of us also got about 15 minutes handling the controls from the co-pilot’s seat. The two weeks of training at the Amphibious Training Center in Little Creek was well done and useful, and being near flight operations at Saufley Field was interesting. Other aspects of our training in Pensacola, however, were sometimes poorly planned and, especially on the Cabot, demeaning. For me, the best parts of the summer were my virtual circumnavigation of the United States by train, and the short visits to Chicago and New Orleans. Junior Year -- 1949-50I moved into the fraternity house at the beginning of the quarter, and my social life became more active.

Although my financial support from my family had been increased to $200 per quarter, my additional expenses again

put a squeeze on my budget. In November, I began "hashing" in the fraternity house -- alternating between cleaning

up after breakfast and serving at lunch, or cleaning up after lunch and serving and cleaning up after dinner. The

"hashing" reduced my board bill by one-half, and saved me about $28 per month. My three summers work with the U.s. Geological Survey inclined me in the direction of geology and geophysics. I considered geology to be a more interesting field than civil engineering, for example, and I was not interested in other engineering disciplines. Geology held the promise of more outdoor work, in more interesting places, than a civil engineer was likely to encounter. Geophysics was a relatively new field, and seemed to combine other sciences (e.g., physics and math) in searching for new oil fields, for example, in a more challenging way than straight geology would. I had always done very well in math in high school, and did not anticipate the tremendous difficulties that calculus would give me. I had fifteen units plus P.E. in the Fall Quarter: 4 units of Chemistry; 5 units of Psychology; 3 units of Electrical Engineering; and, 3 units of Naval Science (Navigation again). My P.E. was again the NROTC rifle and pistol class. I was a member of the team; we had several local matches and, in December, flew in a Navy aircraft to Southern California for a four-way match with the NROTC teams from Cal, UCLA, and USC. I did not record and do not recall how we placed, but do remember that the smog in Los Angeles was so bad that one’s eyes would water while trying to sight in on the target. I finished the quarter with one A (in Psychology), three Bs, and a disappointing D in the Electrical Engineering course. For my Winter Quarter, I had 18 units scheduled: 5 units of Chemistry (a final B grade), 5 units of Historical Geology (B grade); 5 units of Anthropology (a C grade -- after hardly going to class except to take the tests -- for a course where the textbook and the lectures were a waste of time); and, Naval Science, where the Marines were now able to take a course taught by Major (soon LtCol) Clifford Quilici, the senior Marine in the NROTC unit. The first course was "History of War," taking us all the way back to the Persians and the Greeks. Although it only counted for three units, it was a very interesting subject, with excellent reading material. I received an A grade. My GPA for the quarter was 2.89. At the Spring Break, I was able to get a ride on a Navy DC-6 from Moffett Field to Sand Point Naval Air Station

in Seattle, and the same transportation to take me back south for the beginning of Spring Quarter. My fraternity elected a President and Vice President to serve half of a school year each. At the end of Spring Quarter, I was elected Vice President. The only real function of that office was as Social Chairman. It also meant an almost automatic promotion to President after the Rush activities in January, 1951. All Juniors at Stanford took Graduate Record Exams during the Fall Quarter. In April, the school selected a cross-section of 350 students -- from all majors and grade ranges -- to volunteer to take another 16+ hours of testing. I was selected and accepted, because the testing paid $1 per hour. I took 6 1/2 hours of tests on each of two Saturdays, and another 4 hours later, for a very welcome $17. Summer Training -- 1950The Marine NROTC students spent eight weeks at Quantico, Virginia, instead of going on another summer cruise. For some reason, only two of my letters home from Quantico were saved. They must have been filled with details of the daily routine and not too interesting. However, the two letters sum up much of what I remember of that summer. I drove my auto home to Auburn, Washington, but had to leave by train the following day for Quantico. At Quantico, we were divided into two companies. Both companies were billeted at MCAAS Brown Field, at the extreme southern end of the base, and about three miles from the main facilities such as the theater, the PX, the clubs, pool, etc. There was no bus transportation on the base, and the only way to travel to the main part of the base was by taxi -- which was very cheap, but inconvenient. In a major change from our previous two summers training, we were given privileges to use the Officers’ Club and Officers’ Golf Clubhouse. One company was billeted in a brick barracks, near the mess hall. Our company was billeted about 1/4 mile away, in a wooden barracks building. I described the barracks as " ..very comfortable, spacious, and clean. We even have a waxed floor -- which means we don’t have to swab it." (The supposition about swabbing was soon proved wrong.) My platoon was billeted in the squad bay on the second deck of the eastern wing -- overlooking the Potomac River, if the view had not obstructed by the double-decker bunks and standing lockers. After two days of orientation and drawing a full set of utilities and all other equipment, including both an M-1 rifle and a .30 caliber carbine, we began training on the rifle range. I described our first Friday's schedule as follows:

(The date of the letter, 25 June 1950, was also the date that North Korea invaded South Korea-- but we hadn’t heard that news yet.) Our staff platoon leader was 2nd Lieutenant Charlie Opfar. He was a slender, ram-rod straight officer, with a blond crew cut and very blue eyes. Opfar had enlisted in 1942, and had several rows of campaign ribbons from action in the Pacific. He had been selected for OCS, and was commissioned in the summer of 1949. Besides being a picture-perfect Marine, Opfar was an exceptionally fine officer whose demeanor and actions were closely watched -- and admired -- by the pre-Marine midshipmen. (My Marine Corps "Blue Book" indicates that Charles Opfar, Jr., was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel in 1965, and was still on active duty in that rank on 1 January 1971. I assume that he retired as a Lieutenant Colonel.) The hostilities in Korea provided urgency to our training that summer. The American/UN forces were not doing well. Most of us could expect to be commissioned the following June and sent off to Korea soon thereafter if the war was still going on. We followed the developments closely -- principally by reading the New York Times and Washington Post every Sunday. I knew next to nothing about Korea when the war broke out. In the following few months while in NROTC summer training at Quantico and during the following year in college, I got to know a good deal about Korea from reading newspapers and magazines. Further, I wrote my term paper in a political science course during that year on the Chinese Communists and their perceived objectives in Korea. Much of the research for that paper came from articles in the "New York Times." At the end of our second week on the rifle range, we fired the M-1 rifle for record. I scored Expert. During the following weeks, we also fired the full qualification course for the carbine, but I don’t remember if it was for record. We also had familiarization firing with Browning automatic rifles (BAR), .45 caliber pistols, and finally, machine guns. Our other training included the usual basic subjects: inspections and drilling; lectures and practical work on the mechanical operations of the rifle, carbine, and machine guns -- to include, of course, disassembly and rapid reassembly; fire team and squad tactics -- both demonstrations and practice; obstacle courses; and, hikes with minimum equipment and hikes with full field equipment and weapons. We were probably issued field manuals on the various weapons that we were becoming familiar with, but I do not remember much "book" study. We were rotated through the "leadership" positions of squad leader, platoon sergeant, and platoon leader. Our schedule always ran until noon Saturday, and most of us used Saturday afternoon for catching up on sleep and readying uniforms and equipment for the following week. I must have gone on liberty to Washington, D.C. (by train) at least once, but do not recall it as being memorable. Further, there was no time to even think about playing poker. I wrote another letter home on the Monday of the final week. I reported that we had had a triple inspection the previous Saturday (personnel, barracks, and rifle inspections) followed by 1-1/2 hours of drill, but that many of us had relaxed that afternoon swimming in the pool at the Officers’ Golf Clubhouse, and had taken in a movie that evening. In that letter I also wrote that we would spend all day Tuesday firing machine guns, that Wednesday would be our big amphibious operations day (landing and assault on beach), and Thursday we would have four hours of tests and platoon drill competition. We were to spend Friday checking out, and be turned loose early on Saturday morning. Several others and I had developed a Sunday routine that we would continue the following year during Basic School. The "others" always included Jerry O’Keefe and Bernard (Mick) Trainor from Holy Cross, and, later, Wes Hammond from the Naval Academy. I wrote home that was almost standard: " ..up at 0800 and off to mass at the main base; then stroll up to Waller Hall (the Officers’ Club) for mid-morn breakfast and the Sunday papers; back here for lunch and two hours of sleep then up to Waller again for a drink and the Sunday buffet supper -- a superb day. This Sunday buffet supper at Waller is almost an institution around here -- about the best, most economical meal I’ve ever heard of. Last Sunday the menu ran: roast beef, mashed potatoes, corn on the cob, roast Long Island duckling and applesauce, crab and shrimp salad, rolls, peaches, pastries, and coffee -- all for $1.25 About half of the officers and their families or dates show up for it." I caught the Capitol Limited out of Washington, D.C. Saturday afternoon, boarded the Great Northern Empire Builder in Chicago on Sunday, and arrived in Seattle on Tuesday morning. A few days later, I was back at my usual post-training summer job -- on a construction crew, bucking a jackhammer breaking up old taxiways at Boeing Field in Seattle. (The manager of Boeing Field had owned the newspaper in Auburn when I worked in the print shop, and was a family friend. Fifteen years later he would become my mother’s second husband.) Changing MajorsIn my final letter home from Quantico, I had written: "I’m eager -- like everyone else here -- to be done and heading for home, but I’m also decidedly looking forward to coming back for Basic School. As a matter of fact, I want to be here next fall (1951) to go through Basic School with this class -- something that my schedule drawn up for the next five or so quarters doesn’t permit. I’m going to change that, if I possibly can, and collect my commission as soon as I can -- but I’ll discuss that with you when I get home." I studied the Stanford catalog of courses and requirements before the Fall Quarter began. I calculated that I could graduate as a History major by taking an additional 38 quarter hours of History courses, plus a 5-unit Political Science course (to complete my "Humanities" requirement), and, of course, the required 9 hours of Naval Science. The schedule as I worked it out required 18 quarter hours in Fall and Spring Quarters, and 17 hours in Winter Quarter. There were a number of reasons behind my decision to change majors:

Senior Year -- 1950-51My first task upon returning to Stanford was to meet with my Geology advisor, and then an advisor with the History department to change my major. The Mineral Sciences advisor had difficulty understanding why I would change my major, since my grades were satisfactory, with a B average. For Fall Quarter, I signed up for a 5-unit History of England course, a 5-unit course in American Social History (taught by Professor George Knoles, who would become my seminar leader for the Winter and Spring Quarters), a 5-unit Political Science course on Contemporary Governments, and the 3-unit Naval Science course "Military History and Politics," a continuation of the previous quarter’s studies. In a letter home in October, I reported that "All of my courses are very interesting ... it is almost a pleasure to study something besides chemical formulas and mineral names." I stated several times during my Senior year that I was studying half as hard, enjoying it twice as much, and getting straight A’s. In fact, I did receive straight A’s during the year except for a B during Spring Quarter in a History course, Europe Since 1901. The drill day for the NROTC was just as unpopular and onerous as ever. We rotated through all of the command positions in the battalion for training purposes, but the Marine students had had so much drill during the summer that it was difficult to be patient with the inept lower classmen. For the Winter Quarter, my courses were: 5-units of Great Britain Since 1760; 3-units of The American Revolution 1760-90 (taught by Professor John Miller, who had won awards for his biography of Sam Adams and for one of our texts, Origins of the American Revolution); 3-unit course on 20th Century American Culture; 3-unit seminar on American Social and Intellectual History; and, the Naval Science course on Amphibious Warfare. In January, 1951, I surprised my fraternity brothers by declining to become President of the fraternity. I explained that I was grateful for the offered honor, but that I was carrying a heavy course load in a new major (and still hashing in the fraternity), and felt it was important to concentrate on my studies and get ready for a commission in the Marine Corps. (An additional, but unspoken, reason my declination was that Theta Xi fraternity was holding a national convention in San Francisco in the spring, and our fraternity, and especially the President, would be deeply involved in the planning and organization of the gathering.) For the Spring Quarter, my courses were: Diplomatic History of the United States (taught by Professor Thomas Bailey, a brilliant lecturer and author); 5-unit Europe Since 1901 (in which, as I mentioned, I got my only B for the year); 5-unit seminar on American Social and Intellectual History; and, the 3-unit Naval Science course, a continuation of Amphibious Warfare. The 5-unit seminar required a thesis from original sources on any subject relating to the1890’s. I chose to write on "Pictorial and Other Humor in Publications." Since 1890 was the decade during which newspaper comic pages began, and magazines such as "Punch" and "Life" were printing cartoons and dozens of jokes in each issue, I had a lot of sources -- and spent many, many hours in the library’s stacks doing research, but enjoying it much more than I had in any science lab work. I finished my college education with 195 quarter hours of credits (180 were needed for a degree) and a final grade point average of 3.23. I was graduated with a BA in History "with distinction," the Stanford equivalent of "cum laude." My biggest regret about my four years of college -- then and now -- is that I did not change my major earlier. There were many, many interesting courses that I could have taken instead of the Mineral Science and Calculus courses. And, of course, my grade point average would have been higher as well. There is a final chapter to my last few days at Stanford. The Senior Ball was held at a country club near Walnut Creek on the evening of Friday, June 15. On the way back from the affair, about 6:00 AM, I fell asleep at the wheel of my Chevrolet and ran almost head-on into an oil tanker and trailer. Fortunately, the driver of the truck saw me crossing toward him and turned the tanker enough so that my auto struck it a glancing blow. My car was wiped out from the center of the hood to the rear fender on the driver’s side. We spun around and off the road, but were lucky enough not to roll over. Since my date and I were both relaxed (asleep), our injuries were not serious. Friends came along soon after the accident and transported us to the Stanford Dispensary for the necessary patch work. My date had extensive bruises on her legs and side, and I had two or three cracked ribs. The dispensary wrapped tape around my chest -- and I was commissioned that afternoon, June 16, 1951. The following afternoon was the Graduation Ceremony. On the day following that, Monday, I had to make several arrangements: since I was not going to be driving my car to Quantico, I arranged for a Transportation Request from the Navy for train travel from Palo Alto to Quantico; together with my parents, who had come to Stanford for the commissioning and graduation ceremonies, I traveled to Walnut Creek and paid a $15 dollar fine to a Justice of the Peace for "crossing the center line;" and, I sold my wrecked auto for $150 salvage. The next day, my parents started for home and I boarded a Southern Pacific train headed for Quantico. NROTC DifferencesThere are principal differences between the NROCT of 1947 and that of 2001. Currently there are 69 NROTC units, and the program is available at over 100 colleges and universities that host NROTC units or have cross-town enrollment agreements with a host university. For example, there is no NROTC unit at Stanford, but Stanford students may participate through the unit hosted by the University of California, Berkeley. How the classroom work and drill schedules are coordinated is not explained in the internet article. Since 1972, the NROTC program has been open to women applicants. In 1990, the NROTC Scholarship Program was expanded to include applicants pursuing a Four-Year degree in Nursing, leading to a commission in the Navy Nurse Corps. The annual goal for ROTC commissions in the Navy is 1050, while the goal for the Marine Corps is 225. NROTC scholarships now provide tuition, books, fees, and $200 per month. Computers are not provided. Graduates will receive commissions in the Reserve components. Those commissioned are "obligated to a minimum of 4 years of active duty." TBSMy parents saved 19 letters that I wrote home during this period, so I have a fairly complete record of the training provided during the months at The Basic School. (I am fortunate to have these letters because otherwise many of the weeks would be only a blur in my memory.) I also revisited an article published in the April 1996 issue of the Marine Corps Gazette. Entitled "On Going To War," it is a rather light-hearted recollection of TBS and the following six months in Korea written by a member of the Ninth Special Basic Class, LtGeneral Bernard (Mick) Trainor. I have borrowed some of his descriptions and comments for use in this segment of my memoir. I attended TBS from 23 June to 15 December 1951. Those dates are a little misleading, however, because the Ninth Special Basic Class actually began on 30 July and ran until 15 December. The weeks between 23 June and 30 July were a little different in character -- and much slower paced -- than was the schedule when the 9th SBC began. TBS had at least three Special Basic Classes operating at the same time while I was at Quantico. There were two classes located at Camp Goettge, an outlying base at the farther reaches of the Marine Corps Reservation, about 24 miles from the Main Base. There the lieutenants were billeted in Quonset huts. I believe that the Officers’ Mess was one part of the general Mess Hall. I don’t know what recreation facilities they had there, or if there was some form of bus transportation to enable them to travel to and from the Main Base. Additionally, TBS also hosted the NROTC summer training. That training, I believe, had been reduced to only six weeks during 1951, because we moved into the barracks that the NROTC group vacated just before we began our 20-week Ninth Special Basic Class. Our barracks were the same ones we had occupied during NROTC training the previous summer. They were located at the end of MCAAS Brown Field, about 4 miles from the facilities -- such as the theater, Officers’ Club, pool. etc. -- at the Main Base. One company was billeted in a brick barracks near the Officers’ Closed Mess, and our company was billeted in a wooden barracks across the railroad tracks and about 1/4 mile from the Mess. By coincidence, I was in the same squad bay that I had been in the previous summer; it was on the second deck of the eastern side of the barracks, nearest the Potomac River. (By an even greater coincidence, my younger son was billeted in the same squad bay when he went through OCS in 1978.) The Ninth Special Basic Class consisted of 347 second lieutenants. Forty-nine were graduates of the Naval Academy, nine came from VMI, and four from The Citadel. The remainder had been commissioned from the NROTC program, except for about 30 who received their commissions through the PLC program, and were graduates of various colleges around the country. Perhaps 25% were married. Although they generally lived with their wives in small apartments in Fredericksburg, Virginia, they also maintained bunks and lockers in the barracks. We also had one Reserve 1st lieutenant in our group during the weeks before the 9th SBC began. He had a wife and four children at home in Georgia. He knew, as did everyone else, that he had been recalled to active duty by mistake, and that it was just a matter of time before his records worked their way up to someone’s attention and he would be released and sent home. He provided one of the lighter moments when, during a rifle inspection, the staff Platoon Commander reproached him with, "Lieutenant, you have lint in your bore!" He responded. "Impossible, sir. I haven’t put a patch through it in weeks!" The Commanding Officer of TBS at the time that I attended was Colonel David M. Shoup. He was awarded a Medal of Honor for his actions at Tarawa, and later was Commandant of the Marine Corps from 1 January 1960 to 31 December 1963. He spoke to us several times during the basic course, and was an interesting speaker who always added an anecdote or two to his subject. My one "close" experience with Colonel Shoup was on the pistol firing range. I was on the end of the relay line when Shoup took the place next to mine. He was wearing full dress greens (including rows of campaign ribbons, topped by the blue ribbon with white stars for the Medal of Honor). He was an expert shot with the .45 caliber pistol, and put most of his rounds in the black bulls-eye -- all while chewing and occasionally spitting tobacco. The "instructors" at TBS need to be described in three groups. The staff Platoon Commanders were all 1st lieutenants. The Company Commander was a newly promoted Major. They were all Reserves who had been recalled to active duty during the previous year. We were all surprised that Reserves would be used to oversee a class that was at least 90% Regular officers. The latter fact would not have been too important if they had not been such miserable, petty, and generally disliked specimens of officers. For example, my Staff Platoon Leader for the 5 1/2 weeks before the 9th SBC began had been in Special Services during WW II, and had been commissioned shortly before being released from active duty. He had been sent through a TBS class before our class convened and then retained as a staff "instructor." He was observed one time in Washington, D.C., wearing his summer service uniform -- the material was actually the Air Force "pink" material, and we referred to him thereafter (privately, of course) as the "Hollywood Marine." He was replaced by another Reserve 1st lieutenant when the special basic class began, but the new one was not an improvement. The duties of the staff officers at the platoon and company level included: conducting the personnel and rifle inspections each morning, and barracks and clothing inspections when the schedule called for them; holding unscheduled "field days" in the barracks when the whim hit them; leading PT and the conditioning hikes; training us in drill and formations; writing up "chits" when a level of appearance or performance did not measure up to their standards; and, holding short interviews to tell each of us individually what our class standing was at the end of each of our three grading periods. Near the end of the first month of our 20-week Special Basic Class, I wrote home: "Our staff officers haven’t improved much, but everyone takes it a little more philosophically now -- we have gotten so we just laugh and shake our heads instead of bitching. As the expression goes, "The only safe procedure in this outfit is just to stay bent over, because you never know when you’re going to get it." The manifest failings of this group were all the more obvious because we had had such superb staff officers during our NROTC training at Quantico the previous summer. Many of the instructors for our classroom work and field problems were veterans of Korea, and most had combat experience during World War II. I don’t remember any of them as being particularly good classroom instructors, but that may have been the fault of the subject matter, the classroom facilities, and our schedule. It is difficult to appreciate lectures held in metal Butler buildings that were very hot (cooled only by large floor fans) during the summer months, and very cold during the fall and winter months. Further, sessions of four hours of lectures on such subjects as the detailed functions and parts of rifles, machine guns, and other weapons after we had spent part of the night and/or morning on a field problem, or after a 0430 reveille for six hours of weapons firing, tended to induce sleep rather than rapt attention. The instructors for the field problems were excellent; their previous combat experiences and the effort that TBS put into adding realism to the problems was much appreciated. I particularly remember Major Gerald Armitage, who lectured on and led the demonstration on "Company in a Night Attack." I was fortunate to have him, by then a Lieutenant Colonel, as my battalion commander for part of my tour in Korean. The School Troops, who oversaw and guided us on weapons firing, during demonstrations, and field problems, were -- as expected -- experienced, knowledgeable and patient. Besides admonishing us with experiences learned in combat ("Don’t bunch up! One mortar round would get you all!" "Keep your heads down and you will live longer!") they helped us learn many of the foibles and practices of life of the infantry in the field (e.g., that our 1:25,000 maps could be preserved and kept dry by encasing them in the plastic wrappers from radio batteries; or, that the standard rifle lubricant freezes in very cold weather, and that the graphite in a lead pencil was the preferred lubricant for a weapon’s moving parts). The instruction during our weeks at TBS can be explained by breaking our weeks at TBS into the same four parts that the school used:

Jack DempseyI completed Basic School at Quantico in mid-December, 1951. I was one of 82 2nd Lieutenants who received orders to report to Camp Pendleton ten days after New Year's, 1952, for immediate airlift to the 1st Marine Division in Korea. We were scheduled to be at Pendleton only long enough to get a series of shots, and to complete a week of cold weather training at Pickle Meadows in the Sierras. My girlfriend during my final five months of college was Cora Lea "Corky" Woolard. Her parents lived in Beverly Hills, and Corky was going to return to that home after completing her degree during the Fall Quarter at Stanford. She invited me to spend the New Year's days with her and her parents in Beverly Hills. The Woolards also owned a small beach house at Zuma Beach, just north of Malibu, and it was thought we might get in some hours on the beach if the weather cooperated. Corky's father had tickets to the Rose Bowl game--where Stanford was to play Illinois--and I could continue on to Pendleton on January 10th. Since I was heading straight for combat in Korea, I had a duffle bag and a small, canvas Val-Pack full of uniform clothing, a few sport shirts and slacks, but no civilian suit. My wear in the evening, therefore, was my Marine green uniform. Mr. Woolard took Corky and I, and her mother, of course, out to a restaurant/night club in Malibu for our New Year's Eve celebration. Mr. Woolard, at that time, was the Managing Editor of the Los Angeles Examiner, and knew scores of people in the Los Angeles scene. One of the people that he knew was Jack Dempsey, who then owned a restaurant in downtown Los Angeles and also lived near Malibu. Jack Dempsey and his party, including his daughter and her husband, and perhaps a date, were in the booth next to ours. There were greetings and introductions all around, and enough small talk to indicate that Dempsey knew the Woolards well. The men were all wearing tuxedos, and I must have been somewhat conspicuous in my green uniform, embellished only with the shiny gold bars of a 2nd Lieutenant. There was a good band, and Corky and I danced often. Sometime after dinner, Jack Dempsey approached the table and invited Corky to dance. They danced one set, the band paused and then started a second set, so Corky and Dempsey remained on the dance floor and completed the long set. When Dempsey brought Corky back to the table, Mr. Woolard said, "You had better be careful, Jack, or you will get the Marine Corps after you." Dempsey laughed and said, "No thanks. I tangled with the Marine Corps twice and that was enough!" For those not too familiar with the history of American prize fighting, I will add a short explanation. Jack Dempsey became Heavyweight Champion of the World in 1919 by knocking out Jess Willard, "The Pottawatomie Giant." Dempsey lost the championship to Gene Tunney in September, 1926, and was again defeated by Tunney in a second fight in 1927. Gene Tunney had served in the Marine Corps in France in 1918, and was frequently referred to by sports writers as "The Fighting Marine" or "The Manly Marine." Camp PendletonI was ordered to report to Camp Joseph H. Pendleton, Oceanside, California, by 0800 12 January 1951, after TBS. That was a Monday. I had been enjoying my visit at the home of my college girlfriend in Beverly Hills since just before New Years, and decided to report in a few days early. We were billeted in an old, musty World War II BOQ in Area 17. The BOQ was so far from the main facilities on the base that we had to be bused to chow and our scheduled activities. It was also 20 miles from Oceanside, the first stop for transportation to liberty in Los Angeles or San Diego. I went back to Los Angeles on Saturday and Sunday, 10-11 January, and took several friends with me. Our schedule at Pendleton started with a rush on 12 January. We were given the first of a series of shots, fed lectures on frost bite, first aid, and venereal disease, and issued 45 pounds of cold weather gear. It was clear that our group was being high-balled through the schedule, and were being slotted ahead of others who had spent weeks at Pendleton. We were scheduled to depart for the Cold Weather Training Center, "Pickle Meadows," near Bridgeport, California, on the evening of 14 January -- but storms in the Sierras brought that departure to a halt. The snowfall was so heavy and blizzards so severe that the highways going up the Owens Valley to Bridgeport were closed; the Southern Pacific Railroad had a streamliner stranded in the snow near Donner Pass for several days; and, the Marine Corps could neither get the group at Pickle Meadows out nor our group in. (The group ahead of us on the schedule ended up spending 14 or 15 days at Pickle Meadows; men from that group who I talked to later described those days as not only the worst they had spent in the Marine Corps, but in their life.) We were told that if we didn’t leave for cold weather training by noon on 16 January, we would not go to Pickle Meadows, but simply maneuver around Pendleton for several days because our air transport could not be delayed. However, our group of 2nd lieutenants and about 200 enlisted troops boarded buses and departed northward on Saturday night, 18 January. We got as far as Bishop, California, by 0800 Sunday, but then were stopped because the highway going north was impassable. We milled around the buses and Bishop until 1500, when it was decided that we would train in the area to the west of Bishop, at "Buttermilk Flat." The buses took us several miles up the hills and we then hiked in for another two or three miles before setting up camp that night. The snow was knee deep, but the temperatures did not get below 0 degrees to 5 degrees at dawn -- and we were all impressed with how well the cold weather gear worked. The parkas were heavy and warm, the cold weather "mickey mouse" boots were great, and the sleeping bags were what we had needed during our last days at TBS. We were even issued air mattresses. We ran a night patrol and raid the first night, had 6-mile hike and patrols on Monday, and broke camp and hiked out before dawn on Tuesday. We got back to Pendleton about 1700 that day. Our officer qualification jackets were stamped "Certified: Winter Warfare Qualified."