|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Arthur LeRoy MorneweckNovi, Michigan- "We knew nothing about the political problems in Korea--we just wanted to go back to the States." - Arthur LeRoy Morneweck

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

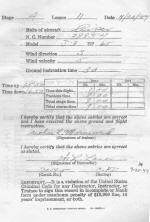

Memoir Contents:Pre-MilitaryI was born on October 9, 1922, in Butler, Pennsylvania, a son of Weston G. and Augusta B. Brandonburg Morneweck. (The first Jeep was made in Butler and accepted by the Army in World War II.) My siblings were Emmit (born 1905), Dorthy (born 1907), Evelyn (born 1909), Virginia (born 1911), Arthur (born 1922), and Robert (born 1925). We attended Butler Baptist Church, which was pastored by Robert T. Ketcham. In Butler, my father was a foundry coremaker. We lived across the street from a grocery store, and when I was very young I would scribble on a piece of paper, take it to the grocery store, and tell them this was from my mother for candy. They gave it to me and later my sister paid for the candy. My Uncle Alf (whose wife Evelyn was songwriter Stephen Foster's niece) went to Detroit and was General Foreman at Ford Motor Company in foundry. He got a job for my father, who became a foreman in this foundry. My mother was a housewife. We, of course, moved to Detroit when my father got the job with Ford Motor Company. I don't remember what year this was, but we rented a house on Barlum Street in Livernois, West Warren area. I have a lot of childhood memories of living in that neighborhood. Between our house and West Warren was a very large vacant field from Martin Street and Livernois. The circus always set up their tents there with elephants, lions, and other acts. We helped while the circus was in town and get free tickets. One problem for the circus, however, was that we kids had built caves in this field and covered them. Sometimes the circus tractors got stuck. A block away was the Good Humor Factory, where we got Good Humor ice cream bars. Our grocery store was a corner house that sold groceries and meat. The grocer's family lived in the rear of the store. The store was closed on Sundays, but if we needed something we could knock on the back door and he would take us through his house to the front where the store was. In the summer we blocked the street water drains and played in the water. A horse and waffle wagon came selling waffles with powdered sugar on them. Next door Bob's mother would take us to Michigan Theater to see the Lone Ranger on the stage. We had two theaters close to us--the West End and the Granada. At the corner of West Warren and Livernois was Lincoln Motor Plant and in front was a large Abe Lincoln sitting in a chair. I remember that every Lincoln's birthday our entire school walked the three blocks to the statue. In those days I had a film projector and showed Mickey Mouse films in the garage. The admission was a button, paper clip, safety pin, or any small item. We played ball all the time in the large field a block away. Usually there were not enough players, so right field was out. We did not lock our doors and never had any problems. When I was about 13 years old, the house we rented was given to the owner's daughter and we had to move. My Uncle Alf knew a man who was selling a house on Larchmont and Ironwood Street, and my father bought it. I played sand lot baseball whenever I could. When I was about 14, I played hard ball with Ford Motor Ball Club. My brother was manager and many games had only eight men to play ball. That is when he had me play. Very few boys had a car, but I was one who did have one. Actually, it was my father's, but I always drove it. We hung out at Simone Shargabain ice cream and candy store at Grand River and West Grand Boulevard. Upstairs was the Lucky Strike Bowling Alley, and next door was Beacon Theater. Some of the guys were Chuck Coons, his brothers Fred, Merle, and Babe, then Art Sheabal, his brother Harry (we called him Kitche), Don who was my next door neighbor, Wilbur Crans, the Goodman boy, Clifford Ong, Bob Kerr, Wesley, and others. I attended Hanneman Grade School in Detroit, and Cass Tech High, graduating when I returned from World War II in 1946. During my school years, I worked for a small, neighborhood grocery store delivering groceries and doing odd jobs. I don't remember the name if it had one. In 1940 I worked in the National Machine Products defense factory. We had bowling teams and I went to Brunswick and ordered a new bowling ball. When I came out and was walking down Woodward, a store had a sign that said "Learn to Fly." I thought that sounded good, so I went in and signed up for lessons. I remember when Pearl Harbor was attacked. Chuck Coons and his brother Fred, Harry Schebel and I had just come out of the Riviera Theater and saw the newspaper. We were all stunned. My brother-in-law, Virgil Terry, was married to my sister Virginia. He was the manager of cosmetics at J.L. Hudson's Department store in downtown Detroit. He was past the age of being drafted, but thought he should get in the service, so he enlisted in Marine officer's training at Quantico. He was a Marine officer in the South Pacific on Bougainville. I have his diary that tells about crossing the Equator. In 1942, I was 19 and waiting to enter the Air Corps. I took flying lessons at a small airfield outside of Detroit. The 50 horsepower Piper Cub was our plane. Take off procedure was to go to the takeoff runway, turn the plane 90 degrees, rev the engine to top power to make sure we had power to take off, turn back 90 degrees, and take off. I was taught to fly a rectangle course, make a 360 degree loop, and fly upside down. I also learned how to stall, put the plane in a spin, and recover. The instructor shut the engine off and I had to look around to find a place to land. When we were a few feet from the ground, the instructor started the engine and it took off. Some planes had two gas tanks and before this maneuver, the student was to switch to the second gas tank. One time a student forgot to switch to the second gas tank. A few feet from the ground, the instructor turned on the motor, but there was no gasoline. They crashed and both were killed. I got a happy feeling when I was flying. One time my instructor told me to take AT-6 and go up for a couple of hours and practice loops, spins, stalls, and chandelles. Then coming back to the field I was singing, and feeling happy. I turned my radio off and did not watch the tower. I just landed and went back to the ready room. I got chewed out for that. My first solo cross country flight was to Saginaw, Michigan. After about a half hour, I was lost. This was not a problem in the small Piper Cub. I climbed higher, flew a large circle, and looked for any thing to help. Off in the distance I saw an airfield, so I flew there. I landed and then taxied. It got real windy. I put on the brake to not get blown off the runway. When I took the brake off, the plane was blown towards the edge of the runway. Now all I had to do was give the engine more power as I took the brake off, but this was my first time without an instructor. I shut the engine off and pushed the plane to the hangar. The old-time flyers had a good laugh. I got gas and flew back home. I did not feel any danger because the 50 HP Piper Cub could easily land in a farmer's back yard. That was why pilots did not wear a parachute. In the Army Air Force, we always had to wear a parachute. The PT-19 Stearman had an open cockpit and double wings, and was 220 horsepower. The AT-6 Texan was 650 horsepower. In 1942 I received my civilian pilot's license at Hartung Air Field at Gratiot and 10 1/2 road. The next year, I joined the Enlisted Reserve Corps or ERC, and finished flying at Hartung Air Field on July 13, 1943. The Air Corps did not immediately accept me when I tried to join because, at the time, I had a three-tooth removable bridge. They gave me time to have a dentist make it a stationary bridge. The following (from "History of Scott Field", 7-7-43 to 3-1-44, Ch. I, pps. 16-19, Ch. XVIII, pps. 670-671) explains the E.R.C. program:

Meeting MickyI was 20 years old and had never been on a date. About 1942, Simone Shargabain moved his ice cream and candy store out of Grand River to South Clarendon Street. That is where I met my love Micky (Charlotte) Matthews. Sometime after I joined ERC, I went on a double date with my neighbor Don and his girlfriend and her sister. There were two reasons why I went on this date. One was that I was the only one with a car. The second was that Micky's mother would only let one of her daughters go on a date if a second daughter went along. (Micky had six sisters.) Don and I picked the the Matthews sisters up at Simone's store and went to Eastwood Amusement Park at Gratiot and 8 mile. It was a long drive from Detroit's west side. I was paired with Blanche, but her sister, Charlotte (Micky) was a great looker, and I thought she was the one for me, even though she was Don's date. In the park, we came to a large barrel that we were going to have to walk through as it turned. As we stood there, I looked at Micky and thought to myself that she was beautiful. How I wished that she was my date and Blanche was Don's. We walked through the barrel and took the girls home. That was the end of our double date. We all had a good time together. It was more like a friend's outing than a date. Two nights later, Micky was on her way home from her job at G.M.C. She stopped at Simone's soda fountain shop where I was having a frozen Power House candy bar. We talked a while and then Micky turned on the fountain counter seat and said she had to go home and that it was two blocks away. I asked her if she wanted a ride home and she said sure. While driving her home, I asked her if she wanted to go for a ride and she said yes. We drove to Belle Isle in my father’s 1940 Ford. One section was a parking lot that faced the river and was a place to watch the boats go by. There was no open parking space, so we had to ride around the island. A couple of times riding around I thought how I would like to stop and kiss Micky. When we came to the bridge, there were about five or six driving lanes that all turned right and led traffic back off the island. Luckily I was in the 6th lane that took us over the bridge or we could drive straight and go around again. Something in my heart said go straight, and I did. This time there was a parking space open. I parked and we had our first kiss. We watched the boats and then Micky said she had to go to the bathroom. We left and stopped at the first bathroom. It was padlocked. I looked at my watch and it was after midnight. The second bathroom was locked too. Going across the bridge, Micky said she really had to go. I knew that if we turned left to go home, we would not find a restaurant, so I turned right and found a restaurant about two blocks away. I stopped and Micky used their bathroom. About four months later, we got engaged. Training in FloridaOur engagement took place about two weeks before I had to leave for basic training in Miami Beach, Florida. On Monday, August 2,1943, I left my girlfriend and sister Virginia at the Detroit, Michigan Central Depot. The train took about two hours to get to Chicago. On it I met another fellow going to Chicago and he taught me how to play chess. We went to the Army recruiting office and had lunch. The Sergeant said it would be hours before we left and we should go to one of the theaters near there. About six or eight of us went to the theater and sat in the balcony. There were only two other people there--a guy and his girlfriend, I think. After the movie, we went back to the Sergeant and then left Chicago at 7 p.m. There were three of us to a section. The two seats changed to two beds and the overhead opened for a third bed. After flipping a coin, I got the upper bunk. I was now not feeling so good. I cried myself to sleep this first night away from home and my soon-to-be bride. From 1942 to 1945, Miami Beach played a significant role in World War II. Nearly 500,000 men, including matinee idol Clark Gable, took over 300 hotels and buildings for housing and training headquarters under the Army Air Force's Technical Training Command. By the time the war ended, one-fourth of all Army Air Force officers and one-fifth of the Air Corps' enlisted men had been trained in "the most beautiful boot camp in America"--Miami Beach. Another group of hotels and buildings served as an Army Redistribution Station for infantrymen returning from battle. These men were reunited with their wives, and "ordered" to have fun before being released or reassigned. We arrived in Miami on August 4, where Army trucks took us to Miami Beach at 11 p.m. We checked into the Netherland Hotel on the beach of the Atlantic Ocean. There were two men to a room. The first morning, the sergeant walked on all the floors blowing a whistle and telling everyone to fall out in front of the hotel in four lines. We were marched (walked) to the Tide Hotel for breakfast. Our meals were served in the basement of the Tide, and the building was painted green. Servicemen were not too happy with the food, so they gave the hotel the nickname "Green Latrine." As we lined up to go in, a young girl and boy used to walk alongside of us selling orange, pineapple, and grapefruit juice. I always bought pineapple juice. We were in 414 T.G. Flight A, A.A.F.B.T.C. No. 4. Our instructor was a little short sergeant who had all of his clothes tailored, even his work uniform. After five days training, I had to have an operation for hemorrhoids, so my training did not actually start until October 4, 1943. I was a love sick cadet. I missed my Micky. In the hospital lunchroom, I was sitting behind the ward boy when I heard him say that a cadet was going to get a medical discharge from the Army. I thought it might be me (although I don’t know why), so I stayed near my bed for a week. When I recovered from the surgery, I started basic training again. I kept a diary in 1943. Following are some of the entries:

The training consisted of watching movies, being marched to the drill field, listening to lectures, and getting shots. A typical day consisted of getting up at 5:10 a.m. At 5:45 we fell out in front of the hotel and marched to breakfast. Then we marched back to our hotel to make our beds and clean our rooms. At 7:00 a.m. we marched to the drill field (which was a golf course). Our training took place on the city streets and golf courses and theaters. Since the Air Corps had taken over 300 hotels on the beach, there were no civilians on the beach. There was also no dirt to crawl on during training--just good sand on the beach. We trained until 11:00 a.m., then marched back to our hotel at 11:30. We got our mail at 11:45, then went to chow (lunch) at 12:00. After the meal, we went back to our hotel to clean it up again. At 1:00 p.m. we marched back to the drill field and trained until 2:45. We got back to our hotel at 3:15. We changed to our bathing suits and walked across the street for physical training on the sand beach. We finished P.T. at 4:45 and went back to our rooms to put on our Class A uniforms. We had Retreat at 5:15 and chow at 6:25. The rest of day was ours. There was a 9 p.m. blackout regulation, which meant that no lights could be on after 9 p.m. We had to be in bed at 10:00 p.m. On November 1, the blackout was cancelled. We trained six days a week with Sundays off. I went to church on Sundays in town. The Army told us to watch our money. I found a store that sold money belts and I bought one. It was just a belt with a wide part that held dollar bills. I met Sal Garafalow (a New York gambler) and his wife Florence. On some weekends, I went to their apartment for dinner. Sal always played poker and won. He was about 19 years older than the rest of us, but a very nice person. Most nights after dark I walked across the street from my hotel at 1330 Ocean Drive and stood on the sandy shore just relaxing, and thinking of my Micky. At nights we went to the P.X. for a ice cream soda and to listen to the big bands play. All through my time in the service they played music and it always brought memories. Micky's and my favorite songs were, “You will never know how much I love you," and "You went away and my heart went with you." According to my diary, the following was a typical day as an Army Cadet in basic training at Miami Beach on October 18 1943:

Once I dropped the M-1 rifle and had to clean rifles from 6 to 8 that night. Tent CityOn Sunday, October 24, 1943, we left Miami Beach Hotel at 1 p.m. and arrived at Tent City at 4:15 p.m. Tent City is where we had weapons training, but I don't know where it was located. We left our hotels and marched north for about four and a half hours with two ten-minute breaks. We were dressed in our fatigues, leggens, and gas mask, and we had a canteen of water. There were no hotels for us to live in during this training. Instead there were 400 tents with eight men to a tent. For the next few days, we eat with our army utensils and drank from a large canvas bag. There were guards all around to keep us from leaving. The only toilets were slit trenches, and I remember that it rained all night. We got chemical warfare training when they threw tear gas among us and we put our gas masks on. The firing range was just across the street.. We fired M-1 carbines, Springfields, Tommy guns, and other weapons. I shot a 142, but don't know if that was good or bad, low, high, or in the middle. I never thought about combat. In my diary I wrote about our schedule at Tent City:

Back to MiamiWe left Tent City on Wednesday the 27th and returned to our Miami Beach hotels. For those who were at Miami Beach, names such as Hotel Netherland, Nautilus, Pancoast, Nausau, Macfadden, Deaville, Edge Water Beach, St. Moritz, Massonettes, Grand Plaza, and Rendale will probably ring a bell. Other memories include eating at Hauffman Cafe and the head count that was taken on November 18, 1943. (With regards to the later, everyone was restricted to their hotels because they lost 147 men.) In November of 1943, I finished training and the other cadets shipped out. I didn't, so I went to the Air Inspector Office to check out my new orders. He looked for my records and said I would be shipped out in 24 hours--and I was. We went by train to Gettysburg College on December 5, 1943. The hardest thing for me in air corp. basic was being engaged to Micky two weeks before leaving. Gettysburg CollegeWe arrived from Miami Beach on Sunday night, mid-night on Dec. 5,1943, and marched about two blocks to the front of "Old Dorm". The upper class officers called out names and gave each their room number in Old Dorm. When Old Dorm was filled there was two cadets left standing and I was one of them. They put the two of us in McKnight Hall. I was put in large room with upper class officers. The next day, Monday, December 6, 1943, was our first day at college. Our first day of classes was Monday, December 13, 1943, and that was the day our class picture was taken. I kept track of my days at Gettysburg with entries in my diary. My first days were as follows:

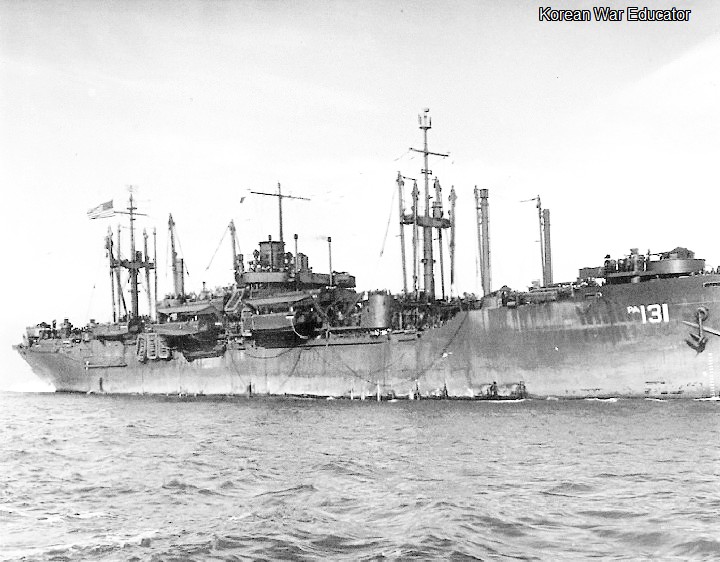

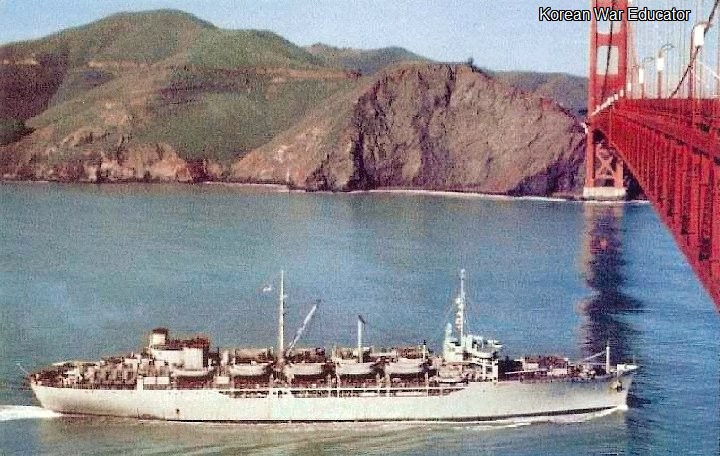

In our dorm room we had a map of Germany and Russia on our wall. Every Sunday night we listened to Walter Winchell on the radio and marked a map showing the advancing Russian soldier. Other nights we went to a professor's home to talk and have lemonade. Sometimes we went bowling. Gettysburg was not a very big town in 1944. The town bowling alley had only two alleys. There was also a small USO, a drug store, and an old hotel. On Saturday, January 1, 1944, I was moved from McKnight Hall to Old Dorm. There was three of us--Dick McKinley from Erie, Pennsylvania, Norm Bullard from Oswego, New York, and me. Old Dorm had a door at one end ground level and inside the door was a pay phone. Walking up to the next floor, my room (shared with two other cadets) was the first room on the right. Across the hall from my room was the cadet officer second in command. His last name was Auton. He was from California. Halfway down the hall was the bathroom and showers. I remember the hall was not heated and we froze going back to our room. On Saturday, December 11, the co-eds invited our class to a welcome party from 3 p.m. to 5 p.m. While living in Old Dorm, I had guard duty until 1 a.m., then went to bed and was called at 4:30 a.m. for another shift of guard duty. It was so cold they had us stand guard duty inside the building. At 6:00 a.m. I was relieved of guard duty, went to eat breakfast, and went back to my room in Old Dorm. I remember that the food was cooked by town women, and it was great. Other memories of Gettysburg College include my drill instructors Captain Coshey, Sergeant Lipschits, and two lieutenants whose names I have forgotten. Each lieutenant was in charge of about half of the squadron. I never had any instructors I did not like. They were all nice. There were about 100 cadets in the 55th CTD Squadron A. At Gettysburg, there were 200 co-eds and 100 male students. I went to Gettysburg College for six months after basic training. I well remember Christmas season 1943. I had been away from my fiancée for only four months when I arrived at Gettysburg College as an Air Corps Cadet. I was a homesick fly boy. I called my Charlotte (Micky) and told her I missed her and was going to go A.W.O.L. and come home to see her. Bang!! I got a stern voice saying, "No, you stay there.” She said that she would come to see me. On Friday, December 24, Micky came with my mother and father. I met them at 9 a.m. The next three days were great. Sunday night I walked (Gettysburg was only a couple of blocks in those days) them to the bus stop. I said goodbye and slowly walked back to Old Dorm. As the old song said, "Tears flowed like wine." On Wednesday, May 10,1944, we went to college chapel and Captain Coshey told us that we had a week furlough because Maxwell Field was not ready for us. I went to the phone at one end of Old Dorm, called my fiancée and asked her if she wanted to get married. She said yes. On May 12, I bought a new cadet hat, jumped on a bus to Harrisburg, and then jumped on a train for Detroit. On the train, the porter looked at me, with wings on my shoulder, wings on my new cap, and humming our song, "You'll never know how much I miss you." The porter said, "Sir, we have a better seat in the car ahead of us." He took me there and I went home in style. I arrived home Saturday morning and found out that we needed some papers filled out in order to get married, but offices were closed. Luck was with me. My future father-in-law had friends downtown, so everything was copasetic. We were married Monday, May 15, 1944, at 7 p.m. We went downtown to the Hotel Fort Shelby. Shortly after arriving there, my wife's sister and our best man came with White Castle hamburgers. We spent the rest of the week on Cloud Nine, floating around visiting friends. World War II marriages did not have tuxedos and long gowns, but they did have everlasting love. On Sunday May 20, 1944, I left my love (boy, is this hard to write), and did not see her for two years while I finished my stateside training and was sent overseas. I returned to Gettysburg College, and from there we were shipped out to Maxwell Field, Alabama, for pre-flight training on May 22, 1944. My Brother RobertMy brother, Robert E. Morneweck, was born on November 12, 1925 in Detroit, Michigan. When he was still in elementary school, he belonged to the Safety Patrol. He then went to Northwestern High School in Detroit and, taking an early interest in the service, he enrolled into the R.O.T.C. program there. He enlisted in the paratroopers on March 20, 1944. I was in cadet training when Robert enlisted, so I don't remember how my parents felt about it. I know they were Christians and believed the Lord would watch over Robert and Virgil. Robert was in the 101st Airborne, 506th Infantry. In spring of 1944 Robert came to see me at Gettysburg College, where I was an Army Air Corps Cadet. Little did I know this would be the last time I would see him. Robert was shorter than me (I am 5’ 10”) but was solidly built. He was so proud when he received his paratrooper wings. The following is from a letter my family received from the father of one of Robert’s buddies.

Robert became part of A company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. He was wounded and awarded the Purple Heart during the defense of Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge. When the wounds had healed, Robert went back to his unit on the frontline. He was killed in action on April 12, 1945. The action in which Robert was killed is described as follows in Rendezvous With Destiny, the history of the 101st Airborne Division. At that time, the 101st was stationed on the west side of the Rhine, in the Ruhr area, just south of Düsseldorf. It was a time of relative quiet for the division.

Ray Boscom was with Robert when he died. He wrote my family on 30 June 1945, when he was at Berchtesgarden, telling us what happened.

Don Burgett, squad leader in A company, wrote:

In another correspondence with Art Morneweck, Burgett wrote:

Don Straith wrote:

Robert is interred in Margraten American Military Cemetery, the only American military cemetery in the Netherlands. His grave was "adopted" by a local family who took care of it until they died. Another member of the community adopted the grave and is now the caretaker for it. Robert's Awards and Honors:

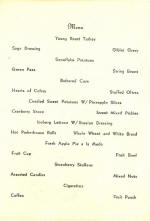

Maxwell FieldI arrived at Maxwell Field, Alabama, on May 24, 1944 for pre-flight training. I was stationed at a large hanger and while on guard duty, I watched pilots practice landing the B-24. During pre-flight, there was in-class instruction on flight theory, taught by officers. We also learned Morse code with the use of ear phones. Morse Code (see Morse in the photo gallery at the end of my memoir) is just dots and dashes--remember V for victory--dot,dot,dot,dash. In a bomber the radio man listened to his home base radio frequency. That was all dots and dashes. In training we listened to a cassette tape. The training was strenuous, and it was very disciplined. We were expected to have our shoes shined all the time, our hair combed, and our fingernails clean. Pre-flight was also the time when the Army Air Corps tried to make each cadet into an officer and a gentleman. We had to sit straight up, not leaning back against the back of the chair. The upper classmen walked behind us with a stick that they pushed down our back so we would not be leaning against the back of the chair. We also ate what was called a "square meal." The fork with food on it started from the plate, then went straight up to the height of the mouth, then straight back into the mouth. We then had to pull the fork out of our mouth, go straight down to the table, then straight back to our plate. A cadet ball was held on July 29, 1944, but I don't remember going to it. We lived in a cottage-type building with a screened-in porch. I think there were four men to a building. We had physical training every morning. I remember that we had to run through the woods and as we came out of the woods, we jumped over a small creek. Pre-flight training lasted from May 24 until August 8, 1944, at which time I left for Avon Park, Florida. I arrived there on August 10 to begin more training and testing. Avon Park, FloridaWe started flying the open cockpit, bi-wing PT-17 Stearman and the AT-6. My civilian instructor for the Stearman was Morley Davies from Center Line, a suburb of Detroit. Teaching me to fly the AT-6 was an Army Lieutenant whose name I have forgotten. He was from Lansing, Michigan. I remember that one day the Lieutenant told me to put on his flight suit, take a package in his car to the town post office and mail it. It was a Christmas present to his wife's mother. I did this and could have been court marshaled for impersonating him. Among my memories of Avon Park is the fact that when we soloed in the PT-17, it was a tradition at Avon Park to be thrown in the lake. Also, once when flying the AT-6 practicing take off and landings, I took off and instead of pulling up the wheels, I dropped the flaps. All I remember was the plane dropped toward the ground and then I was flying over the tree tops. I did not say anything, but a week later another cadet did the same thing. My instructor looked at me and said, “You would not do that, would you?” Another time my instructor told me to go up for a couple of hours and practice acrobatics. I did, and coming back to the airfield, I was feeling happy. I turned the radio off and did not watch the flight tower. I landed on the cemented runway next to the blacktop runway. At this point in the war, the flux of enlistees through the Army Air Cadets exceeded the rate of crew loss in combat. In order to retain these cadets in the Army Air Corps, several months of college classes were added to the training program in order to introduce these mostly high school-educated cadets the basics of college math and physics, as well as introduction to flight. Ten hours of civilian flight instruction were provided in small aircraft such as J-3 Cubs or L-2 or L-3 Grasshoppers. This was more for morale purposes than anything else. Cochran Field, GeorgiaFinally, we took AT- 6 Texan training at Cochran Field, Macon, Georgia. On January 1945, I was given a check flight by a Captain, and one by a Major. The Major said I did okay, but sadly for me, they had too many pilots. When I was told my flying days were over, they said I could pick where I wanted to go. I said I wanted to go as close to my wife in Detroit as I could get. They said there was Chanute Field in Illinois, so I went there. I was there only a few days and was told that they needed men in Germany. I was sent to Gainesville, Texas, for infantry training. A friend of mine went to cadet Springfield College when the program was shut down. He was sent to Scott Field for radio, but volunteered for gunnery school. He was a ball turret gunner on a B-24 and had nine missions. He was in 453 BG at Old Buckingham, England. He now lives in Bangor, Maine. Another friend was a World War II tail gunner in a B-24 in England. He had a hearty breakfast of Kellogg's All-Bran before a mission over Germany. On the mission the All-Bran started to work. He was not going to fill his pants, so he left his tail gunner position and went to the bomb bay doors and relieved himself. When they got back to their base, he really got chewed out by the pilot. All I can think about is the German soldier looking up and plop! He gets it right in the face and says, "American secret weapon"--but it stinks. Infantry Training in TexasAs mentioned in the excerpt from the History of Scott Air Field, there was a surplus of pilots after 1943. In 1945 they had so many pilots they had to put Air Corps men in other jobs. Many were put in the infantry, and I was one of them. I was shipped to Camp Howze, Texas. I walked into the ready room and saw an officer in a dirty uniform. I had never seen an officer in a dirty uniform while I was in the Air Corps until then, and I thought, "What am I getting into…" Basic in the Air Corps was different than in the Infantry. The better of the two was Air Corps basic. I was in 3rd platoon, company “B” 48th Battalion. I did not know any one who did not make it out of basic in ether air corp. or Infantry.. OH there was one in Miami Beach but that was because he was epileptic. I went to Church every Sunday either on base or in town. Nothing was ever said to me. Most men just stayed in bed. Camp Howze had barracks and ground was flats for training and walking-marching I had basic in the air corps, so infantry was a little easier for me. When my day was done I never hung around the barracks. I always went to the camp theater or into town. The M.P.s never gave me any trouble, they just asked me to show them identification. Sometimes I showed my air corps card with no problem. It never bothered me when I was put in the infantry from flying. I had flown before so I knew it was not because I could not fly. Pacific TheaterAfter I finished training, I went to New Jersey and then by train to Pittsburgh, California, where I shipped out for the Philippine Islands. They had decided that they needed men in the Philippine Islands instead of Germany in order to get ready to invade Japan. I was sent to infantry--the 40th Division, 185th Infantry, Company E, 1st Squad, 1st Platoon. After mopping up on Negros Island, the 40th Division had returned to Panay in June of 1945. I was transported to the Pacific Theater on the SS Sacajawea. It was a small transport with only about 900 GIs aboard. The rear half of this ship was all pissed-off ex-airmen who were now in the infantry and the front half housed the new men--18 year old rookies. The rear half never got any KP duty because the new men did it. In fact, we never saw any officers. They stayed in the front half. We left the San Francisco dock at 1700 on June 1, 1945. We slept four high on canvas beds. We just lay around all day, read books, wrote, talked, or slept. There were religious services every other night. On the other nights we had jive sessions with a guy named Tiny playing the organ and other fellows playing instruments. In the afternoon we listened to music coming over the radio. Every fourth day I had guard duty and every morning from 0400 until sunup and every night from 1930 until sundown. We stood at our abandon ship position during general quarters. There was inspection every day of our sleeping quarters. We had to wear a life jacket and carry a full canteen of water all the time. We got 2 1/2 meals a day, but it was so hot in the mess hall we hated to eat. Outside on deck, we could see the Pacific Ocean of pure blue water. On June 9, 1945, we arrived at Pearl Harbor at 1000. There were a lot of ships there and a lot of Navy and Army airplanes flying all over the sky. They had a movie on deck and then I slept on deck because it was too hot in the hole. They had church services on deck Sunday morning. Hawaii looked like a nice place for a vacation. I saw Honolulu when we arrived there. At 1500 on June 14, 1945, we left Pearl Harbor and I had my last day of guard duty. For one week we had been stranded there in the harbor in Hawaii and could not get off the boat. The crew members went ashore and bought candy to sell to us for as high as fifty cents a bar. They got it, too, because we did not get enough to eat to fill us up. The boat PX would not sell candy to us while in port. When we left, we had target practice with our boat's guns, firing at a sleeve pulled by a T.B.F. Avenger. By this time we were with a small convoy. The food on the ship was rotten, so my friend George and I got two lemons from the mess hall and mixed them with water and sugar in a canteen cup. We crossed the international dateline at 0300 on June 22, 1945 and advanced one day. On June 26, 1945, we arrived at the Marshall Islands at 1000. The place was filled with ships. Those islands were small and did not have anything on them. We anchored between a couple of islands. On June 27, 1945, we left the Marshall Islands at 1600 and passed through a lot of small islands. On July 1, we had a couple of real sub alerts. We saw the sub chasers drop depth charges. For three days we had subs playing around with us. Meanwhile, somebody was making a lot of money off the trip. The food was way below standards. They let fruit rot before they would give it to us, and had to throw bushels of it overboard. The PX allowed us one candy bar every two days but eventually they quit giving those out, too. We arrived at the Carolina Islands on July 3, 1945 at 0900. I saw a lot of tankers and aircraft carriers there, but there were no fireworks. On July 8, we arrived at the Philippine Islands at 0800. On Leyte, we had guard duty and worked unloading supply ships. I remember guard duty at night. A Jeep pulled up with a couple of non-coms and a couple of Philippine girls at the PX I was guarding. I asked for some candy bars and when they came out, they gave me one candy bar. Unloading the supply ship, we waited for the DUKS (amphibian land-water craft) and rode them back to the supply area. There was one large tent in which we piled boxes of "10-in-1 rations" in a circle. We opened some for the candy and cigarettes. I did not smoke, so I traded my cigarettes for candy. We got off at Leyte Island at 0800 Monday, July 9, 1945. From Leyte we left at 1700 on July 23, 1945 on an LCI boat. We hit some rough weather before arriving on Panay in the Philippines at 0900 on July 25. By 1400, I was in the 185th Infantry, Company E. On Panay, we trained to invade Japan. It was hot and we had to keep our shirt sleeves down because of yellow fever. I still remember the Lieutenant hollering, "Morneweck, turn your sleeves down." Across the dirt road from our camp was a Philippino house on stilts. The natives were growing peanuts. On our free time a truck took us to town. In town was a two-story whore house that I never visited. I bought hula skirts and mailed them back home. Luckily we used the atomic bomb to end the war. We were training when the bomb was dropped. We only got rumors--one that the bomb was very little, then we were told that it was very big. We did not know for days what it was. We did not react until the war was over. Then we shouted and talked about going home. There was no mail from home--we were moving too fast. Japan surrendered on August 14, 1945, and from the Philippines we were then shipped to Korea on the USS Bandera ADA-131 for occupation duty. This was about September 6, 1945. I remember that on the trip, the first one to see a floating mine was to receive a $25 war bond. There were sharpshooters on deck in case one was spotted. Korea 1945On September 8 or 15, 1945, we arrived at Inchon, Korea to accept the Japanese surrender. I am guessing that we were only about twenty men. I was in the 40th Division, 185th Infantry, Company E, 1st Platoon, 1st Squad. Some names I recall from those days are: Kaiser, Gregory, Calvert, Avery, Gansen, Averett, Graves, Combs, Lewis, Fitzgerald, Fitzpatric, and Edson. We knew nothing about the political problems in Korea--we just wanted to go back to the States. We set up our cots in a large factory that made mattresses. We were not allowed to sleep on these mattresses. The machines in the factory looked like Singer sewing machines. During the day we unloaded metal boxes of 50 caliber ammunition. I needed something to hold my personal things, so I took a box and disposed of the ammunition. We boarded an old train and went to Taegu, Korea, arriving on September 8, 1945 (officially open October 1, 1945). The train ride was very cold and someone built a fire on the floor of one of the Pullman cars. It burned a hole in the middle of the walkway. We were the first Americans the Koreans ever saw. We marched into the Japanese compound past the Japanese guard (they were still at their guard posts) and stopped in front of a 2-story building we were to use as our barracks. Being in the first squad, we marched to each guard post, the Japanese soldier fell in the rear of our column, and one of our men took over the guard post. I took guard of the ammo dump and it was raining very hard. The Japanese soldiers were very cordial and bowed to each of us as we replaced them. When we got back from guard duty the Japanese were gone. The following night we were just getting in bed and the C.O. came in and told our squad to make a full field pack (with rations), and get our rifles and ammunition because of some trouble in town. We packed up (13 in our squad) and were taken to the city hall. We had just gotten there and were standing at the gate when up from three directions came three Japanese soldiers running at us. To us it looked like the whole Japanese army was coming at us. Those rifles of ours got loaded really quick and ready. The Japanese just came up to surrender to us. They were afraid of the Korean police. We were to guard some important criminal and political papers. My guard post was two vaults and it was pitch black. Here comes the kicker.... We were the regular army troops, but we were the only ones there, so we were given M.P. helmets, M.P. armbands, and .45 caliber revolvers. We worked with the Korean Police. We set up our radios in police stations to talk to our jeep. We did not destroy any arms. I assumed the Japanese took them home with them. There was a room that had a few things that we could have. I brought back a sword. There was a city block of houses built side by side. They had no back doors, and they faced the courtyard. There was only one way to get in. We were assigned to keep G.I.s out of a whorehouse district. I don’t know how they got in, but a Korean madam would come out saying, "American, American," and we would have to go in and check each room and kick them out. Every Saturday a doctor examined each girl and gave his approval. One night I had to find a G.I. and when I found him, he said not to turn him in because he had enough points to go back home. I never turned him in, but a month later he was still in Korea, so I don't know how many points he had. One day one of our sergeants was shipped back to the States and our company sergeant called about six of us upstairs and told us about it. He said he was sending my name in to be a sergeant. The next day our squad had clean up duty around the building. We all went outside and started picking up paper and cigarette butts. The company sergeant came by and said, "Art, you are to be behind the men and make sure everything is picked up. That night I was called in and they said there were too many sergeants so I was back to G.I. status again. When we were not on duty, we played touch football, read books, slept, or went to town. In town if you had to use the bathroom, you went to the toilet that had many oblong holes in the floor. You would stand or squat over one. A woman might come in and use the hole next to you. Other than that, when we were at Taegu we (GI’s) had no problems with the Korean people. I enjoyed my time in Taegu. The people were all very nice, but the language was hard for me to learn. There was one thing we said on the phone. I don't know what it meant, but I thought it was "Hello." The phrase sounded like this: "Yaba sol tip o hindy ga." There was a curfew at night. One night we chased someone down the street and then thought, "What are we doing? Acting like Tom Mix?" The natives didn't mind having their picture taken, and when two of us went duck hunting, they went in to the lake to retrieve the ducks. We did not go sightseeing. We did not get to know the people, but I have pictures of their policemen, our barracks, "E" Company squad and platoon, oxen, etc. I really don't remember Christmas in Korea, although I remember that it was cold and we poured oil for cleaning our guns into the barrack stove. Four of us were put at an outpost many miles from town at the bottom of some mountains. Our out-post was an old two-room building. We built a shower with wood and a barrel with a hole in the bottom and a toilet seat to sit on over a hole in the ground. Every morning we found human waste on the seat, so one night we watched for a couple of hours. A Korean came and instead of sitting down he would squat on the toilet seat and miss the hole. I also remember that the Korean toilets were oblong holes in the floor and they had "honey dippers" who took away the human waste and spread it on their food gardens. Everything grew twice as large as ours. For obvious reasons, we were not allowed to eat anything that came from the ground. I don't know how far away we were from our company camp, but every morning a Jeep with a hot stove would arrive and make us hot breakfast. The rest of the day, we got K-rations. One day two of us went duck hunting with an M-1 and a Carbine. We got four ducks. Our job was to guard a large barn. Now if you are wondering what was in the barn that was so valuable that they kept four men there, we were too. So we broke the lock one day and went inside. We found the barn was full of rice bowls. Why--I don't know. He's on second. Later we found out that many miles away, another four-man post was guarding a barn full of parachutes. Going HomeI don't remember how we found out that we were going home. There was a point system and we all had enough points. We knew something when we turned in our guns and they were dunked into some thick liquid preservatives and put in boxes. When we were ready to go home, we got on the USS General H.L. Scott to leave Korea on February 26, 1946. We then stopped at Shanghai, China where they took officers out of cabins and put Chinese people in them. I have a picture of the dock we were at. We then continued to Seattle. I remember that one night there was a bad storm and no one could go up on deck. We docked in Seattle and there were doughnuts and milk waiting on the dock for us. I don't remember if it was the Red Cross or Salvation Army who gave them to us. It was probably the Salvation Army because the Red Cross did not have a very good reputation in the Pacific area. We left California by a train that took us to Camp McCoy, Wisconsin. I was discharged March 20, 1946. Mustering out pay was $300 and I received my first payment of $100 on March 26, 1946. Travel pay was $26.45. These figures do not add up, but that is what I got--a totals of $168.05. After my discharge I took a train home. For the next two months I got $100 each month. Each month I bought Micky a purse. Post-MilitaryI got a job at Ford Motor Company, where I worked for two years before quitting that foundry job. A friend got me a job with Commercial Controls Corporation servicing and programming postal meter machines and the Flex-o-writer. The Flex-o-writer was the main product. It was a typewriter that punched a one-inch wide tape and could read this tape and print it out. For example, it could be used to type a letter. The tape was put in the reader and it typed out what had just been typed. If the tape was glued end to end, the typewriter continually typed the letter automatically. In 1957 the company merged with Friden Calculator. We wired the Flexo to the Calculator and had our first computer. Later we merged with Singer Sewing Machine and then with Thompson-Ramo-Wooldridge. After 40 years, I retired from TRW. We have two daughters, a son-in-law, and grandson. My wife Micky and I celebrated our 57th wedding anniversary on May 15, 2001. Then on December 30, 2001, my Micky went to be with our Lord. I have my children close to me. I am living with my youngest daughter, Toni Ann Morneweck. We live about five houses away from my oldest daughter and son-in-law, Terry and Jack Ellis, and my grandson Tim in Novi. Micky's sister Blanche Rosendale, now lives in St. Clair. We are a very close-knit family. I keep my days occupied with my family, friends, church, and surfing the web on things that interest me like World War II. I don't attend any company reunions, but I do attend 101st Airborne Lunch every month. I was invited because my younger brother was a 101st paratrooper who was wounded at Bastogne and later killed in action crossing the Rhine River. A month ago I had a 45-minute ride in Yankee Air Force B-17 at Romulus, Michigan. I could go any place I wanted to after we were in the air. Final ReflectionsAs this memoir says, I am an old World War II cadet of the Army Air Corps (not Air Force) who was taught to fly the bi-wing open cockpit by civilian instructors. "Remember the stall, spin, upside down, slip, loop, engine shut off, climb, glide, elementary 8--and don’t forget the chandelles." My instructor said, "Give me a Channnndelle.” Some 60 years later, friends from church (Kelly & David Havrilla) had a friend Chris who owned a Stearman PT-17. He asked me if I would like a ride. "Yes," I said, and my mind started working. I remembered wearing fatigues, running out to the plane, strapping on a parachute, jumping on the wing, and bouncing into the rear cockpit. A young civilian girl started cranking the engine. I turned the little switch, and “off we go into the wild blue yonder.” At the Ann Arbor airfield, I met Chris, who owns a beautiful blue, yellow, and white PT-17 plane. I walked slowly out and raised one leg up to the wing. Dave pushed the rest of my body up on the wing. I grabbed the two handles and acted like I was chining myself, but I was really trying to get this body in the open cockpit. Once in the cockpit, Chris put the helmet and radio on my head. Kelly hooked the safety straps on me. Chris started the engine and “off we go into the wild blue yonder." Once up a few thousand feet, Chris spoke the sweet words, “ Art, we will not do any acrobatics today. Take over the controls." Turn left. That was easy. That was the hand my watch was on. Then Chris said he would take over and land. The tower came on and said to go around again, somebody was on the runway. I thought that it must be Kelly. She wanted to go up, too. Kelly’s father owned a plane and she took lessons for a pilot's license. Dave’s parents had a house next to Hartung Air Field where I received my pilot's license. The PT-17 is a nice little plane and it has fixed landing wheels. The AT-6 has retractable wheels and flaps. I know a cadet who, on take off, dropped the flaps instead of raising the wheels, but that is another story. Awards and Duty StationsAwards:I am entitled to the following awards:

Duty Stations:Following is a list of my various duty stations while serving in the military:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Photo Gallery[KWE Note: The glare on many of Art's photo gallery pictures is original to them.] (Click a picture for a larger view) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||