|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Samuel Harvey MerrittGoodyear, Arizona- "My strongest memories of Korea will always be the cold, as well as the thought that any one of the artillery or mortar shells that came at us could be the one with my name on it. For me, the hardest thing about being in Korea was probably just staying alive." - Samuel Harvey Merritt

|

||||||||||||||

Memoir Contents:Pre-Military

My name is Samuel Harvey Merritt. I was born on October 02, 1932 in Pasadena, California, the son of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Merritt. I have two siblings. Both parents held full-time jobs. I went to several different grade schools in the Los Angeles area, and attended John Burroughs High School, from which I did not graduate. After school I worked in a flower and plant nursery, mostly taking care of the plants. Growing up during World War II, we all took part in civic defense activities. Most everybody in school purchased defense savings stamps, and when we had enough, we turned them in for defense bonds. At the age of 16, when I was in the 10th grade, several other guys and I joined the 40th Division, California National Guard. I enlisted to earn extra money. I don’t remember how much my pay was, but it wasn’t much. I had always been interested in the military and this was a chance to join a branch of the army and not have to go away for three years. I also had a chance to learn about all of the weapons, how the army operated, etc. As there was no war involving the U.S. at this time, my parents felt that it would be a good way to get military training while getting paid for it. It seemed to be safe, and it would not interfere with my schooling. We met once a week in the evening for four hours at a National Guard Armory that was located at the end of a landing strip at the Burbank airport. In the summer of 1949, I also attended two weeks of summer camp. Our instructors were World War II veterans who had the experience necessary to train us in combat situations and weapons handling. They taught us army regulations, general orders, etc., and we were taught the proper way to march, etc. The weapons we trained on were the .30 caliber M1 Garand rifle (my weapon of choice), the .30 caliber M11 Carbine rifle, and the .45 caliber pistol. We also had to be able to disassemble and reassemble them. As I was in a heavy weapons company, we were instructed on the heavy .30 caliber machine gun, the 81 millimeter mortar, the 75 millimeter recoilless rifle, and lots of other military-related hardware. Even though there wasn’t a war going on at the time, I took my training seriously. During my 11th year in high school, the Korean War broke out, and as the 40th Division was activated on September 01, 1950, I could not finish high school. I knew nothing about Korea, but ironically my English teacher in the 11th grade, Miss Nedra Thiemig, had been an army officer (WAC) during World War II, and she talked to us quite a bit about what to expect, especially those of us in the National Guard. I didn’t want to go to war, but as a member of the National Guard I was willing to take some other unit’s place in the U.S. if they were called to Korea or some other station. I was a little apprehensive, but I had no idea how long the war would last. I followed the news about it by the newspaper and the radio. We did not have a TV at that time. I wasn't resentful about being activated. Coming so close to the end of World War II, it was still fresh in my mind to serve my country, even though I was still in high school at that time. Also, the fact that I had joined the National Guard kept my interest up in case there was another war. During World War II, when I was younger, my interest in wartime happenings had been kept up because two brothers across the street from us were in the Navy. My mother was pretty quiet about me being called to active duty, but my father talked a lot. We discussed the possibility of my getting out of the National Guard because of my age. (My birthday, October 2, was very close to the activation date of September 1st.) After much discussion, the decision was made to stay in the National Guard and pick up my 12th grade when I got out. So, instead of graduating from high school, the high school age members of my guard unit and I were sent to Camp Cooke, California. (Later, Camp Cooke became Vandenberg Air Force Base.) Activated to Camp Cooke

Camp Cooke was located north of Santa Barbara, California, about 90 miles. The camp was active during World War II, but it hadn’t been used for some time and it was in need of repair. We had to replace broken windows, make sure the doors worked, replace light bulbs, make sure the latrines were in working order, etc. We did this while we were waiting for our guard unit to receive replacements. We were very short of people, but they began to arrive on a daily basis. I don’t know if we ever did reach full strength. Among the camp’s uses during World War II, it had been a POW camp for the captured German soldiers. When we were cleaning up our barracks, we needed some things, so Sergeant Burke, one other guy and I received permission to requisition an army truck and go hunting for them. In the process, we came across the barracks that the German POWs had stayed in. They were very nice and in good shape. It looked as though the POWs were given paint and supplies to do with as they wanted. They even had put up signs with phrases in German. These barracks were fenced in with barbed wire, and had sentry huts. Hence, we were able to see our first POW camp. We were also able to pick up some desks, mirrors, chairs, etc.—all things we did not have. Before the war broke out, I had been promoted to Corporal, so I was put in charge of close order drill (marching and the handling of rifles) and calisthenics. It was a continuation of the training we had at summer camp. It brought everybody up to an "entry level" point and continued on from there, making sure that everybody qualified with the rifles and pistols. In the field we had hand grenade practice, gas mask training with tear gas, training capturing small mock-up towns, experience on an infiltration course, simulated combat exercises, and lots of marching with full field pack and equipment. Indoor classes were held to make sure that we understood map reading, communications, Morse code, first aid, etc. My family was not able to come and visit me as they did not have a car. Also, my parents both worked. My home was only about 150 miles from camp, so I was able to go home occasionally by hitchhiking a ride with one of the guys who had a car. When my training was over, I went home to visit my family and neighbors. My family was apprehensive to know that I was now getting closer to being shipped overseas. My friends were not around when I went home to visit. I wasn’t apprehensive about going overseas myself. I was anxious to see Japan as we all "just knew" that we would not go any further than Japan. (Ha, ha.) Ten Months in Japan

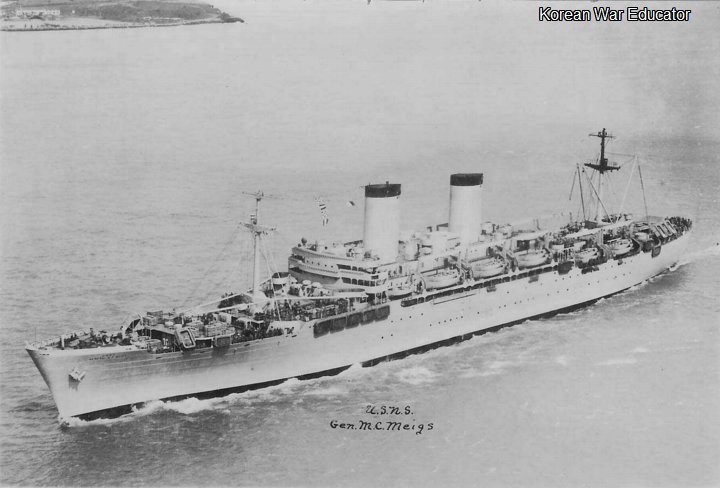

This was not only my first time leaving the States, it was my first time leaving California. I boarded the General M. C. Meigs (operated by the Merchant Marines) for my first voyage on a ship. For the most part, it was pretty much uneventful except for the rough seas that hit us when we were a few days out of San Francisco and a few days out of Japan. The food onboard was handled by each unit’s mess sergeant. As the food supplies were not the best, the mess sergeant had to be very creative. As we approached Japan, we could see Mt. Fujiyama. That was a beautiful sight. I was to spend the next ten months in Japan. Our first camp was camp Younghans in the northern part of Japan. The second camp was Camp Schimmelpfennig located in the center of Japan near the town of Sendai. Our training continued on pretty much the same, but with more hardships and emphasis on combat. We underwent water and food rationing, climbed mountains with all of our equipment, engaged in many war games, had air lift training, experienced real beach landings, had classroom jump training, as well as training in the use of the bayonet, hand to hand combat, Jujitsu, etc. The Aggressors used against us in the war games were Rangers. We all had fears about going into a war zone where we stood a chance of being injured or killed, but I personally felt combat-prepared as a result of all the training we had. Sometimes we got a three-day pass. When we did, we went to Tokyo and saw all the sites, and visited the various shops to buy souvenirs to send home. Where I was in Japan, I did not see any aftermath of World War II. My reaction to seeing the Japanese people was that they were noticeably shorter than Americans. We were shipped to Korea as a Division and I kept my original rank and positions—Headquarters squad, Machine gun platoon, H (heavy weapons) Company, 2nd Battalion, 223rd Regiment, 40th Division. I believe that I was trained very well--well enough that I felt competent going into combat. As I heard a fellow on TV put it, "We were trained to the Nth degree." But that doesn't mean that I wasn't scared. On to Korea

When we left Japan, we were transported by the Sergeant Woodward naval ship to Korea. We landed at Inchon harbor on January 22, 1952 in the evening. As soon as the ship was in port, we got off and lined up to board a train. At the dock, a lady from the Red Cross was passing out doughnuts. About ten paces behind her was another lady passing a collection plate. We were dressed for winter with no money in our pockets. I don't think that that was good timing. An interesting thing also happened at this time. The Sergeant called us to attention for an announcement. He told us explicitly not to talk to or give anything, i.e., food to the South Korean civilians that were watching us. There were women, children, and old men all dressed in rags for clothes that I would not consider giving to the Goodwill. The Sergeant had a very good reason for this. Somebody back in the ranks threw a candy bar out to the Koreans. Everyone else and I could not believe our eyes at what happened. Every Korean dove for that candy bar—every man, woman, and child. It looked like a bunch of hyenas stripping an animal. There was no consideration given to the women or children. Well, I could see what the Sergeant meant. This incident really showed what the South Koreans were going through. When we boarded the train, it was starting to get dark, but what I could see was pretty much like some of the towns that we had left behind in Japan. We could tell that fighting had gone on there, as some of the buildings were damaged and there were craters from artillery and mortars. My brother-in-law was in Korea when I got there, and still there when I left. He was in the Army anti-aircraft group, stationed on one of the west coast peninsulas. I'm not sure where he was north and south. Front Line DutyThe Korean train took us northeast from Inchon for several miles. Since we didn’t go through any populated areas, we didn’t see any of the natives. We were then transferred to open trucks for several more miles travel to the "Tent City" staging area. We spent a couple of days there, then packed up and marched to the rear area of the front line. My regiment was located in the Kumsong area. This area was hilly to mountainous. At that time, the MLR was stationary, not moving forward or backward. The machine gun platoon was mainly supporting the rifle company patrols as they made their rounds every day.

When I got there, I finally got to see what the "front line" was and looked like. I had no idea what to expect because a person’s mind cannot show him what it doesn’t know. Nothing was happening at that time. Things were generally pretty quiet, even quieter when Operation Clam-up came into effect February 10 to 15, 1952. Our artillery was constantly firing at the enemy as "harassment" tactic. This went on all of the time. Right after Operation Clam-up ended, the artillery support was very strong. It was a way of letting the enemy know that we were still there. One thing I did not expect was that when the artillery shells were armed with "proximity fuses", they would sometimes explode when they came in contact with heavy moisture. Sometimes this happened right overhead, and all of a sudden shrapnel was raining down on top of us. Now that was scary. Still, I guess I was holding up as well as any other soldier. As far as fear or being scared, the first night that I was on guard duty was pretty scary because I really wasn’t sure what to expect. These scary times would come and go throughout my stay on the front line—which covered the whole time I was in Korea. I was only in Reserve moving between Kumsong and Kumhwa. I believe that it was two weeks. We were there to rest up. We were living primarily in bunkers and foxholes as, up to this point in time, the positions were fixed and we didn’t need to move them. The bunkers resembled small caves, and were furnished only with our sleeping bags. Like a cave, they were both wet and dry. The foxhole was for our machine gun. We were only in it for guard duty. It was probably about a couple of weeks before we engaged the enemy, and about that long before I saw my first dead enemy. They were two dead North Koreans, frozen solid. I did not see any dead Americans, although I was made aware of two people I knew who were killed while they were in Korea. One was named Ken, but I can’t remember his last name. He was standing the final guard shift of the night at a machine gun position. Just as he was beginning to leave, he was shot in the head by an enemy sniper. The other one was a 2nd Lieutenant from West Point. I can’t remember his name. He was in the company rear when artillery shells started coming in. He didn’t make it to cover in time. As I did not see these men killed, the impact was not as bad as it could have been. Ken had a brother on the front line, but I did not have a chance to talk to him at that time. After I rotated home, I came across the brother, but he did not have much to say. The person in charge of the group I was in was a 2nd Lieutenant. He was an ROTC officer when he graduated from college. The one thing that stood out with the 2nd Lieutenant was his interest in our personal hygiene. He made sure we washed our face, neck, hands, etc. every day, even though it was very cold. It was amazing the difference it made to our morale. Talk about being scared—the 2nd Lieutenant would not sleep at night. He only slept during the day because he was afraid of being killed in his bunker at night. The enemy was good at doing this. Fighting in our area happened primarily during the nighttime patrols. Being in the machine gun platoon, I was not included in the patrols. The machine gun platoon’s job was to give the infantry added support as needed. We were the heavy weapons part of the lighter weapons the infantry carried. We, as well as the .75mm recoilless rifle platoon, were the upfront line support, while the .81mm mortars stayed back at the company rear. These weapons constituted the Heavy Weapons Company. This was the standard distribution for a battalion. I carried my M1 Garand rifle for added protection. I was made even more secure by the fact that there was plenty of support from the rear units that provided the help that was needed in the positions that I was assigned. The 40th Division replaced the 24th Division unit. This left only a few veterans who were replacements to the 24th Division. They didn’t have much experience as they had only been on the front line for a short time. The 24th Division left the front line and went to the rear. The replacements stayed attached to the 40th Division until they had their time in. We stayed in the same place except when we changed positions. It seems as though both sides agreed to settle in on the 38th parallel. In training we had tried to cover every aspect of war plus anything we could encounter in actual combat. We were trained to be combat ready as much as possible so that we could be dropped into battle at a moment’s notice. The one thing we couldn’t train for was the enemy’s real bullets, real mortar shells, and real artillery shells. My "baptism of fire" was incoming barrages of mortar and artillery shells. This took place several times during my stay in Korea. I was never injured by rifle bullets or artillery shells, but several times when the shells exploded, they covered me with dirt, knocked my helmet and other pieces of equipment off of me, and twice that I can recall "duds" landed very close to me. (The duds were even more scary.) The weather was very cold when I arrived in January. It was –30 degrees to –40 degrees. It was difficult to deal with. We had lots of winter gear. At the bottom half, we started with underwear, then long Johns—upper and lower, our wool dress shirt and pants. Next were what we called our "iron" pants. I’m not sure what the material was, but they were waterproof. On top over our wool shirt, we had a pile jacket. Next was a field jacket. We also had a parka when needed. We had a pile hat and two pairs of gloves—a wool pair and a leather pair that went over the wool gloves. The only thing that got really cold were my hands and feet. Though we did have enough clothes, they were not necessarily the best, nor were they necessarily new. For example, I wore a size 12 boot, but the largest that I could get from supply was a size 11 ½, which was okay for fair weather training. The problem was that, for cold weather and snow, we were issued one pair of inserts plus two pair of socks—one thick pair and one thin pair—to wear inside our boots. The insert was okay, but when I put on both socks, my boots were too tight. So I had to remove one pair of socks. Consequently, I got frostbite and spent one week in the battalion hospital tent. The extreme weather also caused some personal weapons to freeze up. This happened on the night patrols and we almost lost some people as a result. I was in only two areas while I was in Korea—Kumsong and Kumhwa. They were both north of the 38th parallel and a little east of the center of Korea. At Kumsong, one of the guys from the rifle company that we were supporting got very nervous on his nighttime guard duty. Every time our names came up together from different lists. On different positions he "saw" the enemy coming up the hill, and started shooting at them. The Lieutenant called me to meet him at whatever position he was at to try to quiet him down (and try not to get shot). Our Lieutenant came up with me, and together we tried to calm him down. To do this, I threw a white phosphorous grenade down the hill to prove that the enemy was not there. This happened more than once. I had a chance to talk to this guy. He told me that he was an American-born South Korean, the enemy knew this, and was trying to kill him. Wow!! The ROK civilian that was working for us as a houseboy was found to be sympathetic to the Communist party and was taken away. I was asked to search his bunker, and I found some enemy ammunition, .32 caliber, Communist pamphlets, etc. The second position I was in while in Korea was the Kumhwa area. I stayed in that area for about two months. On our approach to that position, I had my first experience with incoming artillery. Now that was scary. One shell knocked the EE8 field phone off of my back. After that attack, we went up to our assigned position. It was then discovered that, back at the artillery attack, almost everybody had dropped a lot of equipment they were carrying. It was easier to move fast with less of a load. As I still had everything that I started with, the Sergeant told everybody to drop everything they had left and told me to stand guard over it while they bent back and picked up everything that was dropped. After that initial attack, I think there were about four more attacks. They were not from enemy soldiers. They were just a lot of artillery and mortar attacks, and a lot of dirt and dust flying around. I got two little pieces of shrapnel in my face on the outside of each eye. They went into the skin, not my eye. The strange thing was, I did not know that the shrapnel was in my skin (although I noticed a little blood) until I rotated home. About a couple months later, I had an itching where I was hit. I went to my doctor and he dug out little pieces of metal. I am sure glad that they did not go into my eyes. From the air, F80s gave us support. The air support was with the company to our left and did not affect us, but I believe it was a problem with the group to our left and to the enemy. The planes dropped napalm and apparently accomplished their mission as everything seemed to come to a halt. I did notice that one of the F-80s was shot down. I also remember an incident where tanks fired at the enemy. It caused us some problems when they did. One Sunday morning, a group of our tanks pulled into the river bed directly in front of us and started firing at the enemy bunkers across the way for about ten minutes. When they stopped firing, they turned around and moved out as quickly as they could. This was the first time this had happened, so we did not know what to expect. We hardly had time to move when the enemy cut loose with everything they had to retaliate for the tanks firing. I do not know what damage our tanks did, but the enemy did plenty to us. The EnemyIn the winter, the enemy wore what looked like a quilted material for pants and jacket, and the same for their hat. They were armed mostly with burp guns which were probably about the same size as our "tommy guns." The main difference between the two was that the burp gun was very much faster, but only accurate at close range. Against patrols it was very lethal. As the saying went, "If the first round got you, so did the rest of the clip." There was one guy (a big guy) on patrol as point man and he got a little too far ahead. The enemy dropped out of the trees, one of them turned on the point man, pulled the trigger, and put a cluster of three to four rounds in each knee. Everyday LivingWe tried to keep clean on a daily basis, washing face, hands, and feet as much as we could. We had a couple pair of socks that we changed, too. We took showers as often as they let us, as we had to go to the company rear, we changed clothes at that time also. The longest that I went without showering was one month. Although I thought of those cheeseburgers I loved in the States, we lived off of "C" rations most of the time. There was a chow line of another company off to the right of our position and about a quarter of a mile away. Sometimes my buddy and I would try walking over there, but the enemy thought it was "open season" and they used their mortars on it. It worked. We didn’t make it, so we went back to eating "C" rations again. We tried it again but the enemy was on to us. It was one of those times that one of their shells that landed beside me was a dud. I prayed a thankful prayer for that one. The reason that we tried to get some hot food was that the C rations were not always edible, particularly the corned beef hash. We had a stack of corn beef hash cans in the back of our bunker. We couldn’t even trade them for work from the houseboys. When the Koreans wouldn’t eat it, you knew it was bad. I didn't smoke or gamble in Korea, but I did enjoy our beer ration of Balintine Ale. We got this with our 101 rations once a month. The 101 rations consisted of toiletries, cigarettes, etc. My good friend and buddy—in fact we were together all the time in the Kumhwa area—was J. W. Isaac from Little Rock, Arkansas. We picked each other right off and stayed together. As I left before he did, I don’t know if he made it out of Korea. Isaac and I tried to keep a light and positive attitude as much as possible, and found that it made a big difference. We thought a lot alike. I remember that he was always quoting things from his grandpa that made sense on how to get along in life. J. W. was black, and I saw prejudice toward him and other "African Americans" I served with in Korea. The thing that I thought was in bad taste was being called a "Nigger Lover" by the white soldiers. I never had any trouble with anybody, though. J. W. Isaac is the only person I served with in Korea that I have tried to find through the years, but to no avail. I regret that I have not been able to find him. Through the years, as I have thought back on all of the artillery and mortar barrages that I was caught in, I sometimes wondered why I was not injured or killed. I had dirt piled on top of me from one, and another one knocked my helmet off. Two of the shells were duds that did not explode. One was not real close, but I saw it after the dust settled. The other one landed right next to my right leg. That one I had to ease away from. talk about being scared. I was one scared soldier waiting for the shell to go off. Luckily it didn't. My only conclusion that comes to mind about why I survived these barrages is that I prayed a lot while I was in Korea. I remember that Easter of 1952 brought the Chaplain and his assistant, as well as their pump organ, which was played by the assistant. It was very uplifting. The bad part about that day was an attack early in the morning on a forward outpost almost directly in front of us. It was a quiet attack using knives. The enemy got everybody in that position, including the guard. We didn’t hear about it until later that day. I really didn't know much about the country at that time, except that the communists wanted it. That in itself made it a country worth fighting for. One thing that I should mention is that the South Korean army didn't always know what to do. They had a tendency to disappear at night when they should have left the next day after they were replaced. I have learned a lot more about the country in the last year or so as a result of the Korean War Educator website and many others. I'm glad that I was able to help the Korean people. We have about four or five more makes of cars that we wouldn't have otherwise, and another society not ran by the communists. Things RememberedOne day when I was back in the rear at the battalion aid station being treated for my frostbite and trench foot, we noticed that there was an American fighter plane buzzing the aid station and the artillery area like he was going to make a strafing pass. Suddenly two more American planes appeared and escorted him out of the area. The troops manning the anti-aircraft weapons were getting ready to fire at him when they saw the other planes. Apparently he was lost and thought we were the enemy. Another time during the day, the company to our right sent a man out onto the valley floor that was the main line of resistance (MLR) to check out an old boxcar for an enemy gun emplacement. He worked his way out there creeping and crawling when all of a sudden a machine gun in the box car opened up on him. Well, I have never seen anybody run so fast as this man did. He had his rifle in one hand, swinging it fore and aft, but staying just ahead of the enemy fire. He made it back to concealment without a scratch. I know it was very scary, but standing where I was, it looked like something out of a cartoon. I was glad he wasn't hurt. At that same position one night while on guard duty, I was talking on the "sound powered phone" (no batteries) to the gun emplacement to our right, when all of a sudden the phone went dead. Well, I didn't hear any noise like someone walking around, so I assumed that it was an enemy troop who was sneaking over the line to "sabotage" our rear area and cut our phone line on the way. The next day we repaired the wire. That night we could hear explosions in the rear and figured it was the enemy troop who had cut the wire between our two phones. The next night the phones went dead again, which was a sign that the enemy troop had gone back to his side. Now knowing that the enemy was that good at sneaking over the line caused us to double up on our guard posts. Another thing that was disheartening was when our artillery fired shells over our heads toward the enemy and they occasionally inadvertently exploded over us, causing shrapnel to drop around us. We were told that these shells had proximity fuses that were supposed to explode a certain distance from the ground. Well, sometimes if the cloud cover was dense enough with moisture, it caused them to explode too son. If that happened above us, look out! An article in the newspaper caught my eye the other day. There was a picture of two British peacekeepers in Kabul drinking tea. Well, this brought to mind that, when I was in Korea, rumors had it that the British would always take their afternoon teatime. (Of course, the enemy would have to stop the war until teatime was over.) It is a humorous aspect of Korea that I still remember. Going HomeWhen company headquarters passed down a list to me that had my name on it and the date that I was to leave the front line, I knew that it was time for me to start my trip home. I spent the time getting all of my gear together and chatting with Isaac and some of the other guys. I was glad to leave the front line and go home, but I would miss J. W. Isaac and some of the other guys. By that time, I was underweight because of the bad "C" rations and the fact that the enemy wouldn't let Isaac and me have a good meal without getting in their target practice on us. We rode in trucks to the point of embarkment, and filled out lots of paperwork. We also had to strip of all of our clothing, and then we were "de-loused", showered, and put on clean clothes. I left Korea on May 03, 1952. I made the trip home on the same ship that brought me to the Far East--the M. C. Meigs. I think everybody, including me, was tired and ready to go home. The weather was the same as when we went over. It was rough a couple of days from either port. There was always somebody bending over the rail seasick. The ship made a straight shot to the States, taking about 21 days to get there. I remember that it seems like we all had K.P. duty, and it seems like there were movies. When we got to the United States, it was good to see San Francisco and the Golden Gate Bridge. We disembarked in San Francisco and stood in line to board trucks. Nobody was at the docks to meet us except the drivers of the transportation that took us to Camp Stoneman across the bay, where we finished processing out. After completing the paperwork, the next step for me was to make air reservations at Oakland Airport for my trip home to Burbank, California. I never left California except when I went overseas and came back. As I was released from active duty (June 3, 1952) and had my DD-214 in hand, I went home. Post-Korean WarIt was about a month after I left the front line that I arrived home. A few weeks after that, we had a severe earthquake early in the morning, and it rolled me out out bed. The first thing that entered my mind was that the Chinese had followed me home. I right away opened the front door and saw a flash of light. When I calmed down, I realized that it was only an earthquake and some power poles had been knocked over and some of the electric wires had broken and hit some steel manhole covers, causing the flashing. Korea was still fresh on my mind. I think the fact that I went right to work helped me adjust to civilian life somewhat. The other thing was that going back to the same church made a big difference, as I got right into the activities. I know that some guys go a little wild after getting out of a war and military service, but I did not. I was more interested in getting my life back. Going to Korea made me grow up fast. I reached adulthood sooner than I would have if I had not gone into the military. Serving in Korea gave me experience I never would have had any other way. I was a different person. The experience I had with the explosions from the incoming mortar and artillery rounds, combat, the severe weather, etc., made a big difference in my life. Learning discipline was a help when I got a job, and made it easier to take orders from my boss. I believe it also helped me when it came time to raise a family. I started to work at Lockheed Aircraft in Burbank, California in the machine shop during the same month I got home. My father worked there and it seemed like a good place, so I hired on. I finished up high school by taking night school classes. Most of the students in my classes were my age or older, and had served in the military in Korea or World War II. I then went on to take more classes through an apprenticeship program that started in September of 1952. The apprenticeship program was with Lockheed Aircraft Company in Burbank, California. The title of the program was "Aircraft and Engines" (A&E). It was a state-accredited program lasting four years. It was a classroom as well as hands-on program. I am married and have four children. I stayed with Lockheed, going from aircraft to the space division. In the space division, I started at Vandenberg Air Force Base (VAFB), where Lockheed had a facility. VAFB had been Camp Cooke, where I took my basic training. It started out as Camp Cooke, an Army base; then became Cooke Air Force Base and finally Vandenberg Air Force Base. After VAFB I was transferred to the Sunnyvale facility. We moved up the coast to San Jose, California, which was close to Sunnyvale. I finished up my time there, which came to 35 years. I retired from Lockheed in November of 1987. When we retired, we moved to Arizona and lived in Glendale for a couple of years. Then we moved to the town of Goodyear, where the Goodyear Tire Company started, which is about 20 miles from Glendale. We have been there ever since. Because I took early retirement at age 55, I decided to do part-time work. I worked at a Radio Shack Store for a while, then I spent a couple of years working for a company called "Wheelabrator Clean Water Systems Inc." as a Field Coordinator. I wear hearing aids in both ears, and I believe the damage was caused by all of the incoming artillery and mortar rounds that I was caught in the middle of in Korea. I also had frostbite that causes recurring problems for me. Looking BackThe Korean War carries the nickname "The Forgotten War" because the administration at that time wanted to forget it and leave it buried with all of the dead. Due to the fact that our government did not look at the Korean "police action" as a "war", people didn't talk about it much. Consequently, I didn't either. In fact, I even gave my brother-in-law my tailored Ike jacket (as he was still in the Army). I gave my khaki shirts and pants to my dad. My mom had to shorten the pant legs and they were ready to wear. I went to work, got married, started raising a family, put on weight that I had lost in Korea (about 40 pounds), and went on with life. There were enough things happening in raising a family that I really put the war behind me. In fact, it wasn't until the 50th anniversary of the Korean War that I started thinking about it again. That's what caused me to look for websites pertaining to the Korean War. World War II was known to everybody in the United States. Korea came close to the end of World War II. Our government, as well as the Russians and the British, were still working out "who got what" after the peace treaty was signed. Nobody seemed interested in anything else. Then there was the fact that a conflict in the Far East was not what we wanted. But, as it was coming so quick and with the agreement of the United Nations involvement, there we were, in spite of the fact that no one knew about Korea and where in the heck it was. With the help of the administration at that time not wanting to call this a war, we tended to "forget" about it. Fifty years had to pass before we "woke up". Now there has been a push to bring the Korean War to everybody's attention. I also find that wearing a cap with "Korea" embroidered on it encourages people to ask questions about Korea and the war and comment about their relatives that were there. I told my children about Korea, but didn't get much response, so I did not go into it very far. When our youngest son was in college, he said that it was mentioned in one of his classes about the Korean War and that it was the first time the UN was involved in any kind of conflict like this. Then a few months ago our oldest son, after reading some Korean War websites, realized that he did not know of the severity of the Korean War, including the cold winters. After all of the reading that I have done in the last year years, I think that the United States should have sent troops to Korea. The Korean War was real. At the time it started, the South Koreans did not have much of an Army, and what they had was not well trained. On the other hand, the North Koreans were trained and experienced fighters. If you consider what would have happened to South Korea if we hadn't gotten involved, it is a good thing that we did. Otherwise, there would be another suppressed and Communist-controlled country that the USA and other countries would have had to deal with. I also think that MacArthur going north of the 38th parallel was a wasted effort. The politicians on both sides decided to return to the 38th parallel and stand pat for the rest of eternity. That is the way it is today. I think that the United States should still have troops over there. When you consider that the North Koreans still want to take over South Korea, there better be either the U.S. or some other faction of the UN patrolling the 38th parallel. I have not revisited Korea, although my wife and I almost took a cruise and land tour that would have included Korea and Japan. We decided to go on a different vacation instead. But I would like to see where my "positions" were in Korea to see what it is like now. I think the primary good that the United Nations did for South Korea was to give them a chance to grow economically, and encourage the industries that have come about, i.e., the automobile industry. I feel that my time in Korea was well spent. Medals EarnedAnybody who is in the right place at the right time has the potential of being a war hero. I don't think that it takes a particular type of person to be a war hero. I received one bronze battle star for taking part in Operation Clam-up. I also received the CIB or Combat Infantryman's Badge for being in combat. They have always meant something to me, and even more so since the 50th anniversary of Korea commemoratives were held. As an example, when I e-mailed different things, i.e., all of the websites about Korea, etc., to my oldest son Scott (who is 48 years old), his comment was, "I really did not know all of these things and I had no idea what you went through." We were told that the enemy outnumbered us by quite a bit. In other words, our troops on the front were one-man deep, whereas the enemy's line was about 25 miles deep in soldiers. Our officers brought this fact up periodically, along with a reminder of the possibility that the enemy could come at us at any time, and we should be ready. We made sure we always had our supplies, and even in our leisure time, we kept an eye out for "China Boy" (the enemy). My strongest memories of Korea will always be the cold, as well as the thought that any one of the artillery or mortar shells that came at us could be the one with my name on it. For me, the hardest thing about being in Korea was probably just staying alive. The times when I was in the middle of incoming artillery or mortars were the most dangerous for me as there was no shelter--just open ground. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||