|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||||

Jack F. LarsonTacoma, Washington - "Going up the hill, I saw lots of dead Chinese; some burned and some shot. At the top of the hill I came upon two Marines. One had a shot-up, bloody arm, but was telling his buddy, "Come on, let's keep going. We have them on the run." - Jack Larson |

|||||||||||||||||

Memoir Contents:Active Duty 1945-1949I enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps in 1945, right after I graduated from high school. I was still 17 years old and needed my parents' permission. The recruiter said I would have a couple of weeks after I graduated before I had to report, but it turned out to be two days instead. I went to Seattle, took a physical, and was sworn in the next morning. With a group of other recruits, we were marched to the King Street Station and boarded a train for MCRD, San Diego. End of World War III finished Boot Camp on 10 August and was granted a leave. On the way home, our train had a layover in Los Angeles. A buddy I was traveling with wanted to go up town to a department store. He had never ridden on an escalator and wanted to see what it was like. We found a store and rode the escalators to the top floor. All of a sudden there was pandemonium. The war with Japan was over. It was V-J Day. People were screaming and cheering and we had to fight our way back to the train station. I was really embarrassed when an older lady threw her arms around me and said, "Oh thank you, you are the boys that did this for us." When my boot leave was over, I headed back to Camp Pendleton. I was supposed to report to Infantry training battalion and prepare for the landing on the Japanese mainland. All six Marine Divisions were to be used. About a dozen Marines were with me reporting back to Pendleton. One of them got the bright idea to get off the train at San Clemente because that was closer to Tent Camp 3 where we were to report. Big Mistake! Because the war was over, Tent Camp 3 had been closed up and we had to hitchhike down to the main gate at Oceanside. We reported in about 5:00 a.m. The base was in mass confusion. Our sea bags had been lost and for a short time I was in the 80th Replacement Draft ready to go overseas within 15 days. I had signed a four-year enlistment. At the last minute, several of the men that joined with me at Seattle found out they could switch to the United States Marine Corps Reserves (duration of the war, plus six months). They kept asking me, "What are you going to do for the next four years?" Even though the war was over, a lot of new Navy ships were still being commissioned, and there was a need for Marines to fill detachments. I was picked along with quite a large group to attend Sea School, and we were sent back to San Diego. The Franklin D. RooseveltI arrived at Sea School in September 1945 and left October 18, 1945. I had been assigned to the USS Franklin D. Roosevelt which was to be commissioned on Navy Day, October 27th. Our detachment was made up with 57 privates (no PFCs). Our noncommissioned officers (NCOs) were all regulars that were Pacific War veterans and had never been to Sea School:

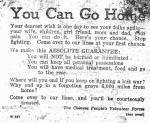

We left San Diego by train on October 18, 1945, and immediately began earning Sea Pay. It took more than five days to get to Jersey City because there wasn't a diner on the train and we stopped for all our meals at Fred Harvey Restaurants. We were taken by bus from Jersey City through the Holland Tunnel and across the Manhattan Bridge to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. We stayed at the Marine Barracks for a couple of days and then we were one of the first units to move aboard ship. The Franklin D. Roosevelt was originally named the USS Coral Sea, but after President Roosevelt died, the name was changed, and the next sister ship built became the Coral Sea. Commission ceremony became a really big event as an honor to our former president. Celebrities attending included President Truman, Mrs. F.D.R., Mrs. Truman, Mrs. Woodrow Wilson, Mayor LaGuardia, Secretary of the Navy Forrestal and Admiral Leahy. Before the ship left Brooklyn Navy Yard, a 50-foot section of the mast was removed so we could clear the Brooklyn Bridge. We went to the Navy Annex at Bayonne, New Jersey to have the mast replaced. We went to Norfolk, Virginia to pick up 115 planes and their crews and headed for our shakedown cruise in the Caribbean. While in port at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, we received orders for a goodwill trip to Rio de Janeiro, to be on hand when Major General Enrico Dutra was sworn in as Chief Executive of the United States of Brazil on 31 January 1946. We crossed the Equator en route and I became a Shellback. During the two and one half years I served on USS Roosevelt, we visited many ports of call. Besides Brazil, Trinidad and Cuba, we traveled to the Mediterranean to join the 12th Fleet in August of 1946. This was a show of force to counter the Communist influence in Greece and Eastern Europe. Ports of Call were Lisbon, Portugal; Gibraltar; Naples, Italy; Piraeus, Greece; Malta; Algiers; Tangiers; and Casablanca. When my tour of Sea Duty was up, I requested and was granted transfer to Puget Sound Naval Base at Bremerton, Washington. I did guard duty on the gates and worked in the Marine PX for the last six months of my enlistment. I received $100.00 mustering out pay and a travel allowance of $1.70 to my home in Tacoma. Marine Corps ReserveTaking advantage of the G.I. Bill, I enrolled at the College of Puget Sound in 1949. Some of my friends belonged to the Marine Corps ready reserve. They told me how much fun they had at drill meetings and summer camp, and I enlisted in the USMCR on 10 May 1950 (to serve indefinite years). Our Tacoma unit was "C" Company, 11th Infantry Battalion, which was called to active duty on 11 August 1950. We left the Union Station in Tacoma on a 13-car Pullman. Seattle had a 20-car train just ahead of us. The train came right into Camp Pendleton to unload us. Large members of reserves were arriving daily and also the regulars, the 6th Marines from Camp LeJeune. They were busy changing their jeeps and trucks identifications on bumpers to 7th Marines. We went on a heavy schedule and began to receive clothing and equipment. We left Camp Pendleton on Sunday, 27 August 1950, and boarded ship in San Diego. We left at dusk on the USNS Thomas Jefferson. On Tuesday, September 5, I went to bed and when I got up in the morning it was Thursday, September 7. We had crossed the International Date Line. My birthday was September 6, so I missed it completely. On September 15, we arrived at Kobe, Japan. The USNS Bayfield and several other transports were also in port. All these ships had to be unloaded and then combat reloaded. We did get one night of liberty in Kobe from 1600 to 2400. Some of "Dog" Company went aboard the Bayfield, but the 1st and 2nd Platoon stayed on the Jefferson. We left Kobe on the evening of 17 September. They Bayfield pulled out first and 22 Marines missed ship. We took them aboard the Jefferson, but their gear was still in the Bayfield. Green BeachWe pulled into the outer harbor at Inchon at 0930 on 21 September 1950. Corsairs and flying box cars were flying sorties overhead. The harbor was full of warships and transports, and a big hospital ship. Destroyers and corvettes were patrolling along the coast. The USS Missouri was firing inland and we could actually see the 16-inch shells arcing through the air. About 1700 we weighed anchor and moved closer to shore. The troops started to debark. Three sergeants and I were left aboard. The sergeants were to watch over all the company gear in #4 hold. I was to watch over all our sea bags in #2 hold, see that they got ashore and stored in a safe place. (Our sea bags should have been left in Japan.) I kept bugging the Chief P.O. in charge of unloading to get the sea bags off but, of course, they were of the lowest priority. About 3:00 a.m. the chief told me he could drop a load of sea bags in the back of a truck going ashore in an L.C.M. After two loads went ashore, the last net load came up and the chief told me to climb on the bags and I was lowered onto the back of a truck. The landing craft headed ashore, and it was 1100, September 22. The truck belonged to the 11th Marines and was towing a 155mm Howitzer. When we landed at Green Beach, the Military Police wanted to send the truck and gear immediately to the front. They wanted us to dump the bags on the side of the road, but I argued they were personal gear and I was responsible for them. We finally found a warehouse that would accept them. I have no idea what happened to the other two truckloads. It worried me whenever I saw little Korean kids dressed in clothing made out of Marine shelter halves. The artillery truck took off and I was by myself. I was told the company would be waiting for me in reserve on the beach. Instead they were sent right to the front. Inchon had lots of units of the 1st Marines and the 5th Marines around, but no one could tell me where the 7th Marines were located. I was directed to a tent where Division Intelligence was located. An officer showed me a large map and pointed to where the 7th Marines were located. Of course that didn't mean a thing to me, so I got on the Main Supply Route and started hitching rides. I rode in jeeps, trucks, and even an amphibious truck filled with North Korean prisoners. 7th MarinesI was walking along close to Kimpo Air Field and it was starting to get dark. An artillery truck came along on an ammunition run. They asked me what I was doing and if I knew the password. I told them no. they said the area wasn't secured yet and I was going to get shot out there by myself. They invited me to spend the night with them. I helped them get a load of 155 shells and rode back to the battery with them. One of the Marines had a watch and let me use his foxhole to sleep in. The only problem was, the guns fired every half hour throughout the night. I started out the next morning and spotted a jeep with a water trailer going in the opposite direction. The jeep had the 7th Marine markings on the bumper and a chaplain was riding with the driver. I rode with them to get the water trailer filled and then we went back to the 2nd Battalion, 7th Marine Command Post. The hill that Dog Company was occupying was pointed out to me. I climbed the hill and finally was back with my outfit. (It was more than a week before the three sergeants made it back to the company.) A couple of days later, we hiked to the Han River and crossed on a ferry at dusk. We walked another three or four miles on the other side and dug in about 2300. We got up before sunrise the next day and left everything behind but rations. Ponchos and ammo. We patrolled through some small towns but met no enemy. The south Korean civilians cheered us as we passed through. In one village, our interpreter had a discussion with the head man and we were astounded to learn we were standing in the middle of a mine field. The villagers had marked where the mines were with circles drawn around them in the dirt road. When we looked close we could see the triggers exposed. Firefight in SeoulOn September 26, Dog Company was dispatched to enter Seoul from the north and meet up with the 5th Marines coming up from the south. The company was actually overstaffed. The roster at this time listed 279 officers and men. At this time I was an extra rifleman attached to Sgt. Reginald Greene's squad (second squad, second platoon). As we approached the city, we crossed a large deep ditch. I thought it might have been a tank trap. Later on when we needed help, tanks couldn't reach us. I don't remember seeing any civilians. It was very quiet. I believe our squad was at the point because there were only three or four Marines ahead of me. I know Bob Wahlbeck was one of them. Passing by the walls of the Sudaemun Prison, I could see a large arch ahead. This was Independence Gate. Then I saw North Korean soldiers, some with high leather boots, moving around. Someone ahead of me yelled, "Sir, there are people in front of us." It must have been Lieutenant Seeburger who yelled back, "Shoot those bastards." The North Koreans were expecting the 5th Marines, and when they saw us coming from the opposite direction they moved to the other side of the roadblock and opened fire on us with machine guns and burp guns. Everyone headed for cover in buildings on both sides of the street. There was a wrecked Russian truck in the middle of the street with a shell hole beneath it. I got under the truck with, I think, three other Marines. Two of the Marines were soon wounded and evacuated. PFC Alvin Neustadt and I were left under the truck. I saw some Marines behind us lying as close to the ground as possible. They were taking "C" ration cans out of their pockets and throwing them away so they could get closer to the ground. Then I saw some little Korean boys dart out to retrieve the cans and disappear again. A machine gun section moved up to the building on my right. They blasted a hole in the side of the building with their gun and opened up on the enemy. Some of them were killed or wounded when the North Koreans fired back and their bullets pierced the walls of the building. PFC Neustadt and I fired back, but it was hard to find a target without exposing ourselves. As the day progressed, the North Koreans moved into the buildings beside us and had us surrounded. Early in the afternoon a sniper fired from the top of a building on our right. A bullet passed through the bed of the truck and hit PFC Neustadt in the belly. There was a corpsman with the machine gunners, but he couldn't get to us. He tossed me some morphine which I administered to PFC Neustadt. However, he died an hour or so later. After almost seven hours and during a lull in the firing, we got word to pull back. I dashed across the street and to the left, and along with others we worked our way through back streets until we reached higher ground and dug in for the night. The next morning we looked down as the 5th Marines moved up and tore down the big picture of Stalin over the archway where we had been fired upon. Our firefight in Seoul caused 13 killed in action and 27 wounded in action. Five of our seven officers had been wounded. More CasualtiesOn the night of September 27 and 28, we had another 14 killed in action and 53 wounded in action. Gerry Winters, a fellow reserve from Tacoma, was wounded and paralyzed from the waist down. We had come under an attack of 120mm mortars that fell on us most of the night. The 3rd Platoon was the hardest hit. The next morning I looked down in the valley and observed an attack on the 1st Marines. A large group of North Koreans shouted, "MANZEI" three times and then started to attack the Marines. The North Koreans were quickly beaten off. As they turned and fled north, we shot down on them but the range was too great and we did little damage to them. On September 30 the 7th Marines were ordered to move close to the 38th parallel and the town of Uijongbu. Our half strength platoon with Sergeant Greene in charge was posted at a small village as a roadblock. We encountered no enemy while stationed there. We all were able to get a haircut and a shave from the local barber. While stationed there, I watched some ROK soldiers interrogating some suspected spies. When they didn't get the answers they wanted, they tried to knock out their teeth with a tire iron. North to ChosinOn October 7, we were relieved from the front and returned to Inchon. We stayed at an assembly area until going aboard an LST Q090 on October 13. This LST was turned over to the Japanese after World War II. The crew was all Japanese except for an American Lieutenant Junior Grade and one enlisted man. Because Wonsan harbor was so heavily mined, we did not land until October 26, and we were extremely low on food. By this time the ROK army had advanced past Wonsan and well up the coast. Marine air had been set up for more than a week at an air field on the beach and even had been visited by Bob Hope and his entertainers. We went ashore in amtracks driving off the LST and up on the sandy beach by the air field. We were met on the beach by an icy wind. We hiked about eight miles to a former monastery which had been pretty much destroyed by the North Koreans. We were there for a few days and were issued mittens, gloves and heavy furl-lined parkas. On October 30, we were loaded in trucks and trailers. We left at 1800 and arrived at Hamhung at 0130, a distance of 65 miles. We moved into some big warehouses. We soon left Hamhung and were taken about 15 miles north by trucks. The next day we moved up by foot to where the 1st Battalion had contacted the enemy. We were resting by the side of the road when an M.P. came along with two Chinese prisoners dressed in their padded winter uniforms. The M.P. said, "Take a good look. This is who you are fighting now." Dog Company was assigned to attack Hill #698. The ROK troops had been unable to hold it and abandoned it when they heard the Marines were coming. As we ascended the hill, our Company C.O., Capt. Milton Hull, called for an air strike. It was getting dark when a lieutenant (I don't remember his name), PFC Ernest Brady and I went over the summit. No one else came up. The Lieutenant was 50 feet head of us when a tall Chinese soldier walked between us. By then it was pretty dark and hard to see, but Brady and I emptied our clips until the soldier was no longer moving. Then we got word to pull back because we were being relieved by Easy Company. It was scary with bullets flying all around, but we didn't want to be left on top by ourselves so we ran back down the hill to the rest of our company. Two days later I found a bullet hole in the collar of my jacket. When Easy Company relieved us we moved to the bottom of the hill in the dark. Four of us carried a wounded Marine down in a poncho. By the time we got down, it was morning and starting to get light. I got about three and a half hours sleep and then tried to move up the road to the rest of our battalion. However, during the night a company of Chinese had occupied the hill between the command post and the rifle companies, effectively trapping and isolating the battalion command post. Dog Company crossed over a hill and came down to the river just across from the hill occupied by the Chinese. There were railroad tracks on our side of the river. Just to the north there was a train tunnel, and we could hear Chinese talking inside it. Across the river, a lone Chinese came jogging down the road. Sgt. Walter Hathorne (our platoon guide) was tracking him with his rifle. He asked an officer (Captain Hull?), "Should I shoot him?" The officer said, "No, it will give our position away." Instead, he called in an air strike. A couple of corsairs soon came and worked over the hill with napalm and machine gun fire. They stopped their attack early because they were getting too close to friendly troops. We crossed the swift cold mountain stream and the water was above our knees. We started to receive fire and I saw Harry Holm stumble ahead of me. He was our radio man and the antenna made him a good target. When he got to the other side of the river, he found out he had been shot in the leg. Going up the hill, I saw lots of dead Chinese; some burned and some shot. At the top of the hill I came upon two Marines. One had a shot-up, bloody arm, but was telling his buddy, "Come on, let's keep going. We have them on the run." (I think this might have been Corbit Ray who lost an arm at Sudong.) Anyway, we secured the hill and when we heard trucks moving up the road, and then a big cheer from the trapped Marines, it made us feel pretty good. Funchilin Pass to Koto-riOne day we loaded on trucks that took us from Sudong up the Funchilin Pass to Koto-Ri. We set up a perimeter defense and it snowed that night and the temperature dropped. I had to stand a two-hour listening post about 100 yards in front of our lines. When I was relieved, I couldn't feel my feet when I walked back to the foxhole. The next day we were issued shoe pacs. These helped to protect our feet but were not perfect. If we didn't change the felt inserts twice a day perspiration would build up and cause problems. One day we stopped on a hill and could see the Chosin Reservoir. The next day we made it to Hagaru. I always felt I was the first Marine to walk into the town. I was the point man of the point platoon as we crossed the bridge over the Changjin River. We met about a dozen civilians who told us the Reds had pulled out about four days before. It was so cold that night they allowed us to stay in houses. One platoon at a time was sent halfway up East Hill to stand watch. When our platoon's turn came, one of our officers gave us permission to have fires. My buddy and I decided to take the risk to bring some wood and have a fire. While on watch on the hill, we watched a machine gun duel on the road below. The heavy machine guns of Weapons Company were firing at the Chinese and they were firing back. The tracer bullets ricocheting about made quite a show. This went on for almost half an hour when a night fighter airplane swooped down and strafed the Chinese gun. He made just one pass and it was quiet the rest of the night. Enemy propaganda posters

Chosin CasualtiesThe next morning our platoon was to go on patrol. Because of the icy trails, our lieutenant said we had to take our shoe pacs off and put on our field shoes. When I took off my shoe pacs I found my feet were so swollen I couldn't put on my field shoes. I had emersion foot, frostbite, and ingrown toenails. Our corpsman took one look and said I had to go to First Medical Battalion that was located in a schoolhouse in Hagaru. I was told to leave my sleeping bag behind because someone didn't have one. At First Medical Battalion, they arranged to send me to First Division Hospital the next day. I spent the night in a large room with 15 or 20 other Marines that had frostbite. There was a large potbellied wood stove in the center of the room, and a five-gallon can of water set next to it. During the night, a corpsman took the can of water around to fill canteen cups for the men. The water was turning into ice and made a clunking sound when put back in place by the stove. Because I did not have a sleeping bag, I spent the night huddled close to the stove. Next morning we were loaded into cracker box ambulances that took us over seventy miles to First Division Hospital at Hungnam. I wound up in a 17-bed ward that had two oil stoves. The doctor told me to soak my feet three times a day which I accomplished by heating water in my helmet on the stove. I also got penicillin shots which made me break out in a rash. On Thanksgiving we were served a complete turkey dinner. At this time, most of the patients had cold injuries, but more were coming in with battle wounds. On November 23, the Secretary of the Navy, Francis P. Matthews, General Smith and General Craig visited the hospital, but they didn't come into our ward. Behind his back, the Secretary of the Navy Matthews was known as "Row Boat" because of his lack of knowledge of Naval matters. He was surprised to learn that Navy personnel took care of the USMC medical needs. I finally had my ingrown nails cut out on November 27, and I thought I might be sent back to the front, but the doctor would not release me. On December 1, we received a large number of wounded and frostbitten army troops. Every day more and more casualties arrived. The number of beds was doubled in our ward and the hallways were filled with men on stretchers. Some of the Army men were troops that were rescued by Lt. Olin Beall and taken from the east side of the reservoir in trucks driven across the ice to Hagaru. They had not eaten for days so I helped the corpsman by brining food from the galley and helped them eat. I remember one young soldier on a stretcher in the hall. He couldn't move his hands or feet. He was cursing out the Army for leaving him on the ice, and praising the Marine Corps for rescuing him. He said he was starving but when I fed him a few bites of food, he said he was full. I guess his stomach had shrunk. A group of us were transferred to the First Marine Division Hospital Annex at Hamhung on December 3. About a week later, elements of the 3rd Army Division moved through our area to set up a perimeter defense for the evacuation at Hungnam. I talked to some of the soldiers who were very unhappy. Their ranks were made up of almost one-third of South Korean conscripts who couldn't speak English and were getting sick because they couldn't adapt to American "C" rations. We had a South Korean guard posted at night outside the hospital. He had a rifle but no ammunition. One morning we found the rifle, but no guard. He had taken off during the night. The local civilians seemed to know we were leaving soon. Fire Fights and PatrolsAround December 10, we were told to pack our gear and be ready to move out. We left about 1500 on a weapons carrier which took us to Division. Harry Holm was with me. His leg wounds had healed. Everyone who could walk was sent back to duty. We spent the night in tents and were supposed to reequip the next day. Before I got my gear, they called all the 7th Marines to get ready to move out. Only one truck was available so I had to wait for the third trip. The truck took us to the port of Hungnam where we got aboard an LCT. We waited about a half hour and then a bunch of Marines came down the beach and marched aboard. I recognized about five from Dog Company. One was Sergeant Hathorne. I asked him where the rest of the Company was and he said, "This is it." I asked where the Battalion was and he pointed to the 100 or so on the LCT and said, "This is it." Just before our reserve unit was activated in Tacoma, I was at the Navy and Marine Corps Training Center, watching the Second Army Division from Fort Lewis embark on the USNS Daniel I. Sultan. This was the ship we boarded to leave Hungnam. While aboard ship, they started to rebuild the Company. We wound up with 44 men, but only 11 of us were from the original Dog Company. I spent three days on the Sultan and got off at Pusan and boarded an LSD that took us to Masan. We went to the "Bean Patch" where a large tent city was set up. (Many of the tents had been riddled with bullets.) The Company was reformed with replacement drafts and we had a nice Christmas dinner. Don Lang came in with the 4th replacement draft. He was also from Tacoma. On December 31, I was promoted to sergeant and became squad leader of 2nd squad, 3rd platoon. We did light training and got acquainted with our new officers and men. The Division started to move out around the middle of January 1951, and we were taken by truck to Pohang-Dong on the east coast. When we passed through Pusan, I observed a large number of North Korean prisoners being marched down the street guarded by U.S. soldiers. A number of them looked at us and gave us the universal obscene gesture. We made a lot of patrols out of Pohang trying to locate and destroy guerilla groups. On one occasion, we traveled a long way on a trail not even a jeep could travel. We came to a small remote village. Our interpreter told us the villagers had never seen Westerners before. They sang a native song for us and Lieutenant Humphreys had us all sing the Marine Corps Hymn. Washed OutOn one of our last patrols which was eight days, we were quite a distance from Pohang and there were not enough trucks to take us back. Our platoon got to ride on tanks, which was surprisingly a smooth ride. Also, the exhaust kept us warm. The tanks were too wide for the roads so we traveled down stream beds and arrived back at camp before the trucks. Toward the end of February we moved again. The whole regiment moved to Wonju. We had to borrow a bunch of trucks and drivers from the army to help out. We stopped at Taegu to refuel and then headed north. We pulled into a bivouac area about 1600. It was a dry riverbed with nice white sand. We got all set up for the night when about 2000 it started to rain. About midnight it became really stormy and the riverbed became a small stream. By 0100 we were getting flooded out. The trucks were in water three feet deep and just barely made it out. A pyramid tent had been set up and that was washed away. Reveille was supposed to go at 0400, but we were moving before 0130. There was a rumor that the Chinese had blown up a dam to flood us out, but actually it was just a flash flood. Hoengsong TragedyOn the way north we crossed the Han River on a temporary bridge. The army had soldiers on it shooting at the ice to break it up. I later learned the bridge washed out anyway, and we were forced to get our supplies by air drop. We unloaded from the trucks at Wonju and moved by foot north. Passing through Hoengsong we encountered the remains of the 2nd Army Division that had been trapped and destroyed. I don't remember too much, but there were dead troops in trucks and fields and wrecked vehicles everywhere, and a team of Marines were trying to salvage an army tank. Grenade AttackWe encountered quite a few fire fights as we got closer to Hongchon. One night we received a mortar attack that lasted almost two and a half hours. On 11 March, Dog Company was attached to the 3rd Battalion to help George, How, and Item Companies as they were a little behind on their objectives. We started moving up a hill and received sniper fire. Nearing the top of the hill we found it had a pill-box looking right out at us from which they kept firing at us with machine guns. First Platoon had been assigned the final assault, and my squad was giving cover fire. First Platoon had the pill-box surrounded but couldn't make it over the top of the knoll because of all the grenades the enemy was using against them. The Marines had used up all of their grenades and were yelling to us to bring them more. I saw one Marine get hit with a grenade and he rolled down the hill screaming. That inspired me to turn to the Marines around me and gather up all the grenades I could carry and run across the ridgeline and distribute them to the waiting Marines. Lieutenant Humphreys and M/Sgt. George Butler were right behind me also carrying grenades. Our fragmentation grenades were much more lethal than the concussion grenades that the enemy used. Our grenade attack was enough to stun the enemy and allow us to get to the top of the knoll and fire into the bunker. I looked down into a trench about ten feet deep and twenty feet long which was filled with Chinese soldiers. We all emptied our clips shooting at them. WoundedAfter securing the bunker, we found several cases of concussion grenades still there. A number of the enemy escaped to higher ground. I saw a Chinese soldier pop his head up from a foxhole and look right at me. I thought, "Good, I'm going to capture my first prisoner." The soldier started to raise his hands and when he stood up, another Marine came up behind me and shot him dead. I never did capture anyone. Hans Schulze was my assistant squad leader. Together we were looking for the best places to set up a defense as it was starting to get dark, and it was decided we would not push further. We became trapped behind a huge boulder, when an enemy machine gun opened up on us. Our own machine guns returned fire and allowed us to get back to our perimeter. I took the first watch and let Schulze go to sleep in a shallow foxhole he had dug. Around 2100, a machine gunner close by called out a challenge. I looked over and saw an enemy soldier in front of our lines. Then we were assaulted by a dozen or more grenades. I saw a grenade come right at me and I dropped to the deck. A piece of shrapnel sliced the left side of my head and blood started running down my face. I didn't have my helmet on because I was on a listening post, and had my parka hood up. I climbed up on the rocks and emptied the 30-round clip in my carbine. Lieutenant Humphreys called in illumination rounds from the 81mm mortars down in the valley. That kept the attackers away for the rest of the night. Our corpsman, Richard DeWert, arrived and started to attend the wounded. Pfc. Evan Thomas was wounded in the left leg. Corporal Schulze had two grenades explode on top of him. His sleeping bag had been ripped open and there were feathers everywhere. He was riddled with shrapnel and lost one of his eyes. We were evacuated the next morning and taken to First Division Hospital at Wonju. My feet were still bothering me, which concerned the doctors more than the head wound. They operated again on one of my toes. One night they brought in a couple of ROK soldiers. They smelled so bad with gangrene they had to be moved. I don't know what happened to them. Back on LineI got permission to go back to duty on the 25th of March. Five of us got a ride on a truck taking a group of new officers to Division. The next day they furnished a jeep for us to take us back to our companies. My company was in reserve and billeted in tents. On April 1 we went back on line. We had crossed the 38th parallel again and on April 5th were engaged in a fight for another hill. This was the battle where Corpsman Richard DeWert was killed. Pfc. Richard Durham and Cpl. Donald Sly were members of my squad that Richard DeWert was trying to rescue. They were also killed. We spent a couple of weeks on the Kansas line sending out patrols and improving our positions. On April 11, 1951, the announcement came that General MacArthur had been recalled and replaced with General Ridgeway. The Chinese started their Spring Offensive and in order to keep the MLR in a safe line, we pulled back to Hongchon. Rotating HomeOn May 3, 1951 I left the company to be rotated home, and Don Lang took over my squad. On May 5, we were at an airfield at Hoengsong. Some four-engine Marine transports flew in with the 8th replacement draft. When they were unloaded, we got aboard and were flown to Pusan. We were sprayed with DDT and issued new clothing. I left Korea on May 9, 1951 on the USNS General Hase. Tom Cassis was the only member of Dog Company that went over on the Jefferson and came home with me on the Hase. We stopped at Kobe on the way. We left the ship and picked up our sea bags on the dock. They were lined up alphabetically and mine was there. I could hardly believe my luck and that the USMC was that organized. We came back to San Francisco and then I was stationed at PSNB Bremerton until released from active duty on July 16, 1951. Citations and HonorsMemorandumThe members of the 1st Marine Division who fought and served in the Chosin Reservoir received high recognition from Major General Oliver P. Smith in Division Memorandum No. 238-50 entitled, "Operations in the Chosin Reservoir Area." The text of the memorandum follows:

Navy Cross CitationThe President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Sergeant Jack F. Larson for service as set forth in the following citation:

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||