|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Milton Lee KeizerFall City, WA- "Never forgotten." - Milton Lee Keizer

|

||||||||||||||

Memoir Contents:

Pre-Military BackgroundMy name is Milton Lee Keizer. I was born on July 3, 1931 at a farm home in Settler’s Township, Sioux County, Iowa, on the opposite side of the river from Fairview, South Dakota. My parents were Gerben Keizer and Amy Lucille Darville Keizer. My father farmed until December of 1935, then he became the owner/operator of Northwest Iowa Feed Company in Hawarden, Iowa. He later owned and operated Hawarden Feed Mill. Mother was a country schoolteacher for a few early years of their marriage, after which she became a homemaker. There were four children in our family: Eugene O., Leroy W., and Doris B. Keizer were my older siblings. I attended Hawarden Grade School and graduated from Hawarden High School in 1949. During my school years, I de-tasseled corn, picked cockleburs, shocked oats, worked in father’s feed mill, and clerked in J.C. Penney’s. I also clerked in the Coast-to-Coast Hardware store, and worked for Mike Dykstra, who was a house and barn painter. For two summers, I worked for railroads, relaying and repairing track. One year, I operated a gas-powered spike hammer rig which weighed 750 pounds and was not self-propelled. One summer I worked for the Milwaukee Road. Another summer I worked for the Chicago & Northwestern Railroad. Besides the work, I was a Cub Scout, then a Boy Scout with Pack No. 209 from 1943 until 1947. I was a Junior Assistant Scout Master from 1946 until 1947. My rank was First Class, plus I earned a half-dozen Merit Badges toward Star. I helped build a Boy Scout cabin in 1946 on a vacant lot between 9th and 8th Street in Hawarden, Iowa, atop Gladstone Hill. I also hiked, made bike trips, attended one summer camp, participated in lots of "soak-um" or Dodge Ball games and other sports. I entered Capture-the-Flag (a game every North American youngster will probably remember) competitions, did a star study, learned compass reading, participated in community help projects, collected tin, scrap metal, and milkweed "kapok" pods in World War II. The fiber inside of the milkweed pods was used as filler in life jackets. My brother, 2nd Lt. Leroy W. Keizer, USAAF, 1094th Signal Corps, was killed in action on Leyte Island on December 6, 1944. Our family participated in the war effort by raising "Victory Garden" vegetables, and observing gas, sugar, coffee, and rubber tire rationing. I walked or rode a bicycle a city mile to fetch groceries home. Joining UpI enlisted in the Marine Corps because I wanted to choose my branch of service and length of enlistment. I wanted to take control of my future. I knew and admired hometown Marines of World War II. Besides, the posters challenged me with, "Do you think you’re good enough to be a Marine?" Yes, I did. My classmates mostly went to the Air Force, although four young men I knew joined the USMC before or after I did. They were schoolmates James Garthwaite, William Bemiss, and Bruce Miller, and classmate Duane Goettsch. My parents’ advice to me after I joined on 19 July 1949 was to "work hard, obey orders, and be a good Marine." I signed up for one year of active service and six years of inactive reserve duty. I left home for boot camp in San Diego, California, and took a bus and train (fare paid by USMC) to get there. Prior to this, I had never been gone from home more than a week or so, when I was working with a "shocking crew" putting up grain shocks one summer. I was barely 18, and back then we did not "leave home" until we married or got a job elsewhere. Another recruit who had enlisted the same day—Jerome Henjum from Humboldt, South Dakota—traveled with me. We were in the same boot camp squad, but were later assigned to different duty stations. We met again in April of 1951 at Yokosuka Naval Hospital, both of us having been wounded in Korea. Boot Camp

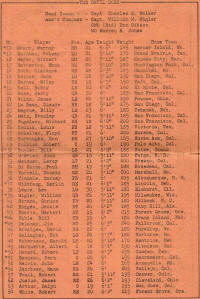

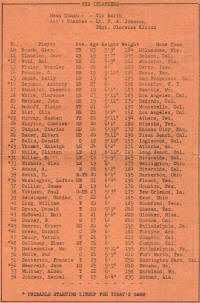

The training camp area at San Diego, California, was flat, sandy, hot during the day and cool at night. When we arrived there, we were assigned to Casual Barracks. Jerry was "chewed out" for bringing acne cream. We were also advised by the drill instructor that, "We were the grass and he was the mower who was going to trim us all into shape." We got our haircuts...short! Our barracks for the remainder of boot camp were two-story, California stucco with red clay tile roofs. There were doors on either end of the building. These barracks are the same ones that are still in use at San Diego today. "Lights out" was 9 p.m. Just before that, we had some free time to read, write a letter, wash clothes, or shine our shoes. The only time we were awakened in the middle of the night was to stand Barracks Guard duty. Boot camp was 12 weeks of learning basic rifleman skills, watching films on health and military equipment, personal fitness, hygiene, map-reading, and drill, drill, drill. We went everywhere as a group. We marched. We lined up for everything from chow to church. We were awakened by lights being turned on at 4:30 a.m. and the DI commanding, "Hit the deck!" Cpl. W.B. "Swede" Henson and Pfc. L.A. Vandervoort, both World War II veterans, were our drill instructors. I thought Henson was very strict. Vandervoort was less so. Henson had the whole platoon drilling again and again for one recruit's error, while Vandervoort "double-timed" us more frequently. There were no black recruits, but several Mexicans were in our platoon. We were a mixture of mostly Texans and Iowans, plus some from other states. The only prejudice I noted was our top DI could not pronounce the name of a Texas-Mexican recruit. Since the name before his was Johnson, the recruit was told to answer at roll call to "Johnson Jr." We were required to take several kinds of tests. We took IQ tests that were supposed to place us in suitable jobs in the Marine Corps. Recruit Johnny Lawyer scored highest and accepted OCS training. I was next highest in score, but was not offered OCS. Nor would I have taken it, since it required signing up for two more years of duty AFTER the Officers School. We also had to qualify on the rifle. We went for a week of rifle training at Camp Pendleton. It was a welcome break from the other training. Held outdoors all day, it was something that I, as a youngster who had been an avid beginning hunter in Iowa and South Dakota, could do well. At the end of the week, we fired at several distances and at different targets. Five or six of us fired Expert and were allowed to return to our tents early the last day and stand "barracks guard" while the rest of the Platoon continued test firing. I was fortunately never in trouble during boot camp. My Boy Scout drilling, as well as the shooting skills acquired from hunting pheasants and rabbits aided me to do things the right way without any disciplining by the DIs. I remember another recruit being punished for wrongdoing. One wiseacre would not accept orders from the "Right Guide" (Recruit Platoon Leader) selected by the DIs. Henson made the two put on boxing gloves and fight it out one night. They fought to exhaustion with no victor. A few weeks later, the Right Guide was replaced. I was Right Guide during the last week, and the wise guy gave me no problems. I recall that there was one recruit who didn't shower frequently enough. A group of fellow recruits scrubbed him down with fiber scrub brushes and Lava soap. He became a regular shower person. During those 12 weeks of training, there were times when I was sorry I had joined the Marine Corps. As I mentioned, it was my first time of extended absence away from my family and high school sweetheart. Also, there were days I despaired whether I could measure up to Marine standards. We drilled in the heat of July, August, and September. At times, I thought the "Marine way" was too rigid, but later knew there was a reason that trained, automatic response was necessary. There were times when the entire platoon was disciplined for the wrongdoing of one individual. When one recruit fouled up the marching drill, we did it again and again. Individual discipline occurred, and mainly was for noise or failing to keep gear clean or orderly. I remember some recruits "double-timing" across the Parade Field in the early evening, carrying two fire buckets (every barracks had these in quadruplicate). They were 3/4 full of fine sand. In my opinion, this collective-type discipline was to teach us to operate as a unit, a team, with every part doing its best job. I did not see any corporal punishment while I was in boot camp, but I heard of one platoon member who had a rifle so dirty that the DI slammed it back into his arms and chest hard enough to bruise his sternum and his stay in "Sick Bay" set the recruit back a week. He graduated with another platoon. Meals were served in the MCRD mess hall. They were filling (I discovered apple butter and orange marmalade, both new to me). And, yes, we had the famous hamburger-in-gravy labeled "S.O.S." and lots of scrambled egg breakfasts. We had lots of chicken, ham, pork, potatoes, vegetables, bread, plenty of fruit, and once in a while, ice cream. Each recruit drew a week's mess hall duty. We had some free time on Sunday, and letters home were encouraged. Church attendance was encouraged, and most recruits went. Marching discipline was maintained, but Sunday was a good day in my memory. The Drill Instructors went a bit lighter on us on Sunday. Also on that day, we participated in Sunday "Smokers" of boxing and wrestling. We got to go see a football game between two Marine teams at Balboa Stadium near the end of the recruit training, but we were under the stern eye of the DI. On the final Saturday of boot camp, there was a Field Day of competitive sports on the Parade Ground. There was boxing, wrestling, and basketball, and our impromptu basketball team took first. We didn't have any drop-outs, although three non-swimmers almost failed. They learned to barely dog-paddle, but they passed the swimming test. When boot camp was completed, there was a parade, review, and inspection by MCRD "brass." A picture of Platoon 27 was taken, rifle badges were pinned on, and Pfc stripes were distributed and sewn on that night. I had obeyed all orders, done all tasks assigned to me, fired "Expert" with the rifle, learned the commands and Corps history, and felt I did belong. I was stronger, more alert, confident, and tolerant of strange people newly met. Even these many years later, I am more organized than before my service time. I like things in my home neat and "shipshape." I make a bed the "Marine way." I also have more respect for other service people, regardless of where they served. Post-Boot CampAfter boot camp, I went home for 10 days of leave. I wore my uniform when traveling, but "civvies" at home. Men from three platoons leased a bus to Kansas City, and from there we spread out to homes, returning to camp in reverse order to this when leave was over. My family and friends congratulated me for passing the test of Boot Camp. I remember that when we returned from Kansas City to San Diego, a PFC from another platoon, who had been drinking, was standing in the well of the bus steps, talking to the driver. On rounding a sharp curve to the left, Cutter lurched backward, hitting the door lever, and fell out of the bus! He broke a collarbone and had to be left at a military hospital near Barstow, California. We heard later that he had been court-martialed for "damaging government property" -- himself. We waited at San Diego for our new duty assignments. While waiting in Casual Platoon, about 30 of us new PFCs were privileged to assist the "Horse Marines" in one final duty at the MCRD. Horse Marines were USMC personnel who rode horses. They were on perimeter guard around the Recruit Depot in the 1930s and 1940s, as well as in parades and formations on the base and in parades in San Diego and other towns. In addition to their other duties, one of their tasks was to ride and care for the horses. Though the horses had been gone for a couple of years, their "legacy" was still piled four to six feet high under tarpaulins in 1949, and covered the size of one-fourth of a football field on the southwest end of the Parade Ground concrete. In October, we "lucky" graduated Marines from Platoons 26, 27, and 28, while awaiting duty assignments, were tasked with removing the very dried remains. Experienced truck drivers backed in from upwind while we shovellers scooped and pitched the dregs into the bed of the truck. We turned and ducked, with collars pulled up to avoid the flying, gritty mist. Then repeated, repeated, repeated. I love to relate that my first job as a "real" Marine PFC was to "shovel horseshit into a high wind!"

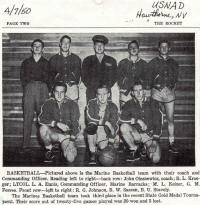

When my orders came in, I was one of more than a dozen new PFCs who were sent as a group to Hawthorne, Nevada. Our train tickets from San Diego to Hawthorne were paid by the USMC. We were allowed a brief stop in Las Vegas along the way. At Hawthorne, I took fire-fighting classes, and was awarded a Firemanship Certificate. I took a military driver training course, and held a military driver's permit. I was a member of the MB/NASD Basketball team that took third place in the Tri-State Tournament in the winter of 1949-1950. On June 30, 1950, I was released from active duty at Great Lakes Naval Center, Chicago. |

|||||||||||||||

Recalled to DutyIn July and August of 1950, I worked for a house painter. Then I began courses at State University of Iowa in September 1950, just like I had planned. When the Korean War broke out, I knew little about the country except where it was and that the Japanese had conscripted Koreans into their Marines since many were taller and stronger than the average Japanese. I figured that I wouldn't be in the Korean War. A few months earlier, I had been released from active duty on June 30, 1950. My expectation was that the war would be over in six months to a year. I wanted to go to college, not to war. By enlisting for one year of active duty and six years of inactive reserve, I had thought that it would allow me to serve my country, then plan on going to college without being drafted. Great plan! Except I got my first discharge on June 30, 1950, only a few days AFTER the Korean War began. Four months later, I was activated. I packed immediately and left SUI. I moved some of my personal things from my bedroom dresser to a large hall storage closet in my parents' home. I visited relatives, and then left for further training. I was sent to Camp Pendleton for infantry refresher training in late October 1950, and assigned to Tent Camp II, Company "C". There, I underwent weapons training on the M-1 rifle, BAR, M-2 carbine, .45 pistol, and .30 caliber machinegun. The training lasted until February 14, 1951, and included training in the field. A few times we also trained with live ammunition firing a few feet over our heads. Our instructors were veterans of World War II and Korea action. When they told us about the hostile geography and the fighting tenacity of the North Koreans, I began to realize that this was a serious war, and not a "Police Action." The training they gave us during infantry training was different from boot camp in that they used mock-ups of Korean buildings and gave us details about North Korean forces, attacks, and behavior. Observers watched as we went through the obstacle course and simulated attack movements, and held critiques of our performance. The biggest challenge of this infantry training for me personally was learning to observe and detect both near and distant danger points and situations. I was in training at Camp Pendleton when the Marines came out of the Chosin Reservoir. I was worried some, wondering about those with whom I'd trained and served. I listened carefully to radio reports, watched newsreels, and read the newspapers. I was very proud of the Marines who had "fought in a different direction" out of the Chosin Reservoir. During this time of further training, weekend liberty was granted. One weekend I ate dinner with a high school classmate and her mother who had moved to the Los Angeles suburb of Compton. Another weekend a friend from my Boot Camp invited me home to his parents' Los Angeles home for dinner. His was a very orthodox Jewish family, and I learned that my plate, saucer and cup were not washed, but broken, since a Gentile had eaten from them and they were then "unclean." Once, a group of six or seven of my fellow re-trainees and I went "on the town" and did some serious drinking and eating. It was near the end of our refresher course. We had trained against simulated enemy forces in simulated Korea situations. This, plus the Marine training I had already undergone, would help me automatically respond to similar occurrences and, even when dead tired, cold and hungry, what I learned from the Marines "kicked in" to keep me going once I got to Korea where so many difficult challenges awaited me. Trip to KoreaOn February 15, 1951, we were on the General George P. Randall, headed for Korea. She was a troop transport that held 3200-3500 Marines, plus Navy crew. I also believe it carried some supplies and equipment. I had never been on a large ship before, but I did not get seasick. Several men were, but I made up my mind NOT to be. I ate lightly the first day out, and stayed on deck as much as possible to get fresh air. I played cribbage with my boot camp buddy Ben Lerman, and played some nickel-dime poker. The trip took approximately 16 days, including stops in Hawaii and Japan. In Hawaii, one afternoon and evening of liberty was given us, so a small group of friends swam at White Sands Beach, visited the park and statue of King Hamehameha, had a Turkish steam bath, and ate lobster and steak at Don the Beachcomber's Cafe. We took the opportunity to "do it all" in case we didn't survive Korea. After leaving Hawaii, we headed for Japan. We altered course to avoid a storm, but still had very choppy, rough seas for three to four days near Japan. I knew Ben Lerman and Charles Crowley of my 1949 Boot Camp platoon, plus a handful of "Company C" troops with whom I went through the retraining course at Camp Pendleton. At Japan, PFC Larry Kelly, a Hawthorne, Nevada Marine, came aboard from a stay in the hospital. He was returning to George Company, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines, and told me that a few other USMB/NAD Marines were in G-3-1, while some other men from Hawthorne I knew were in sister companies How and Item. I never saw any of them. By coincidence, I wound up assigned to G-3-1, Kelly's outfit. Korea - First ImpressionsThe ship arrived at Pusan, Korea, in the middle of the day on March 3 or 4, 1951. We debarked to the docks soon after landing. My first impression of Korea was that it was badly shot up. The town showed the effects of battle, and the trees in the surrounding countryside were shattered wrecks. I could immediately tell that we were in a war zone, because only military vehicles were seen at or near the docks. There were MPs directing traffic, and uniforms everywhere. I was in the last dozen or so Marines that arrived that day to be assigned to a company and battalion. I was sent to the 1st Marines, 3rd Battalion, George Company. From Pusan I was transported to the front in a train whose window glass had been shot out. At the end of the line, I transferred to a truck and was taken on up to my regiment. During the trip up, I saw Korean carriers who had been hired to move heavy loads of ammunition and fuel to the front. This was the first time I saw the Korean "A-frame" in use. It was a home-built, open backpack on which I would later see some amazing loads packed. As my time in Korea progressed, I saw a Korean carry as many as five sections of sawn logs, each four feet long and up to 18 or 20 inches in diameter, on his A-frame. Sometimes they carried four five-gallon cans of water at one time! They carried stacks of mortar shells in their cases and piles of rations so large I don't believe that I could have lifted them. The porter's secret, if they had one, seemed to be that they never set the load down. It was stacked on the A-frame in an upright position, with the frame leaning against a wall, rock, or something else. Then pappa-san, as most porters were called, crouched to get the straps over his shoulders, using his legs to stand upright. Resting was accomplished by reversing this, allowing the long ends of the A-frame to touch the ground while the load was held upright against a rock, tree or hillside, while the bearer crouched to take the weight off. Then with a "hunhh!" the carrier stood again and resumed packing the supplies. To the FrontOn the day we moved up to the front, I saw two prisoners being escorted under guard to the rear. When we went through a napalmed area on the way to join my outfit on March 5 or 6 (not sure which day), I saw a couple burned corpses of the enemy. I felt no qualms about the dead enemy. They were faceless, nameless bundles of burned clothing and bone. Our guide to the front brought us by dark to a safe area and an authoritative voice asked, "Anyone here who knows machineguns? Anyone who knows ANYTHING about machineguns?" I ventured that I knew enough about light MGs to reassemble the breechblock with double-beveled edge up and forward. I was told to come with the speaker, who turned out to be TSgt. Harold E. Wilson, the 3rd Platoon Sergeant, who placed me with the 5th Squad, 3rd Section, Machine Guns. My first assignment was to be an ammo carrier for "Danny's" gun--Jack Daniels. I lugged two cans of .30 caliber, belted machinegun ammo. When I got to the front on March 7, it was nightfall. We were near Chunchon, below the Iron Triangle, and southeast of the Hwachon River. The Marines of G-3-1 were dug in on a hilltop, and would stay there several days in reserve, resting, repairing gear, and filling up squads with replacements. When I got there, besides PFC Kelly, I knew Given Webster, another Hawthorne Marine who had just left the 5th Squad as its gunner. Jack Daniels, who had moved up from assistant gunner to replace Given as gunner, also had been at Hawthorne. I made friends, but you didn't want close buddies because they could be blown away any day, and that would hurt. The closest "buddies" killed in Korea were Boot Camp buddies not serving with my line outfit. I barely knew the G/3/1 Marines killed just seven weeks after I joined the outfit. I knew my Fire Team members, our Squad Sergeant and Platoon Sergeant, plus only a couple of other men. That's it. A "grunt Marine" has a very restricted view of war; sometimes only the backs of the men ahead of him and faces of the few Marines beside or behind him, and his tent mate. I did not know anything about the officers, nor the other platoons of G Company. Capt. Horace Johnson was C.O., and first Lt. Amason, then Lt. John Lindseth had command of the Weapons Platoon, and TSgt Harold E. "Speedy" Wilson was the 3rd Platoon Sergeant. I remember only TSgt Wilson, as I had almost no contact with the officers. At all times while I was with George Company in March and April 1951, we looked to T/Sgt Wilson for experienced leadership and he, being an extremely good career Marine, commanded us well by example and quiet orders. He was 100% Marine, an excellent NCO, brave, cared for his men's welfare and safety, was well-trained, firm but friendly. He taught me how to throw an "open" horseshoe, and I believe he saved my life on Hill 902. I served very briefly under Lieutenant Amason, but I never met him. I got there the first week of March 1951 and he left in early April. I don't know why he left. He was succeeded by Lieutenant Lindseth, who we regarded as a "spit and polish" Marine officer. I only met him once, plus we members of the 3rd Section Machine Guns were in a picture together with him once. It's in our G-3-1 history book, Volume III-IV. He had been an enlisted Marine, taken OCS, and came to us "Gung Ho" and crisply uniformed, full of fresh training and ideas. He cautioned his troops quite frequently about sky-lining themselves, but I understand that, while I was in Yokosuka Hospital recovering from an injury, this new officer did just that himself, and while exposed on a skyline was killed June 6, 1951, with a burst of fire from an enemy burp gun. From Reserve to PatrolsOn my first patrol, I told my squad leader, Cpl. Dick Androsko, that there were a few fish rising in the rice paddies we were crossing. I had seen some little splashes. He told me to move out faster to the valley floor and take cover, because the "fish" were bullets being shot at us from extreme range. That was my baptism of fire, although I didn't immediately realize it. I had an M-1 Garand rifle, with a web belt full of ammo clips and more ammo nearby. I also had a bayonet and two hand grenades. By mid-April, however, I had exchanged the M-1 for an M-2 carbine and two 15-bullet ammo clips taped together for quick reloading. A series of patrols were followed by a couple days in reserve while other units took their turn spearheading the move north. After a week or so of "reserve" status, our 3rd platoon drew a patrol--the "George Company Turkeyshoot"--on Easter Sunday 1951. Our platoon set out across paddies to some low hills, climbed them, and prepared machine gun firing positions that covered a small valley. The idea was that other forces would push the enemy up the valley, thus giving us excellent long-range targets. The enemy fled faster than the trap could be closed. A few scattered bullets were fired at us from a distant cluster of buildings. One bullet creased the inner thigh of one Marine, whose main immediate concern was exactly where had he been hit and was he still capable of fatherhood? No enemies were pushed into our trap, and we went back to our lines. Coming back, with a few random enemy bullets still plunking sporadically around, mortars were called on to cover our return. One "short round" was near enough to our Squad Leader, Sergeant Young, that he received a few bits of shrapnel in the butt and later had words with the forward observer calling the shots. Most of our officers and senior NCOs were World War II veterans. They made sure we knew how to care for our weapons and how to use them, and advised what to watch out for in the way of mines or hidden enemies. They led us less by ironclad command than by example, demonstrating steady, knowledgeable leadership. Also, the veteran combat Marines who had arrived before me showed me how to cook up rations quickly and with tiny fires. In reserve, we learned how to adapt the Korean system of heating houses to heating large tents with gas-fed sand buckets. When I first got to the reserve area in Korea, it was hilly and quite high, but we did not hit the mountain heights until mid-April. We dug foxholes/bunkers whenever we could. These were two-man holes with capacity enough for a third Marine or the machinegun, and most of them had some log walls and partial dirt roofing. It was still bitter cold through March. I wore two of everything I had that I could get on. I wore a dungaree cap, T-shirt, wool shirt, wool sweater, wool GI issue scarf, dungaree jacket, boxer briefs, dungaree trousers, and a wool parka. I was adequately warm in the daytime, but barely warm at night. Life in KoreaWhen I first arrived in Korea, the nights in March of 1951 were freezing cold. I recall only taking about three helmet baths that month. I took several during the soggy, humid days of April. I shaved once a week, and changed clothes about 5-6 times in seven weeks. There was sizzling heat in late July and August. In fact, it got so hot that it melted the film in a tiny 16mm camera I'd bought in Japan, causing it to stick. I never got any photos IN Korea. Meals consisted of cold C-rations, or hot C-rations those times we could have a fire. I missed stateside ice cream, watermelon, pork chops and hamburgers while I was in Korea. I never ate the native food. The best meal I ever ate during the war was a turkey dinner at an Air Force mess tent at Thanksgiving. The ambulance driver stopped to make a pick-up, and we stayed to eat. I also got some care packages from home. My parents, girlfriend, and sister sent cookies, fudge, cold meat rolls packed in popcorn, and gum. I remember that my sister once sent me a block of chocolate fudge. It had melted and congealed a couple of times, but I ate it and enjoyed it, even though it was sugary. My first Squad Leader, Cpl. Richard Androsko, received cold meat rolls and cheese from home, and shared them with me. My family and friends also sent me socks, postage stamps, blank pages of stationery, my large sheath knife, dad's .32 caliber Colt automatic pistol, candles, and a ballpoint pen. We had a semi-official "Korea Mail System" that was standard procedure. You told your correspondents at home to please send you an envelope, two sheets of paper, and a stamp each time they wrote. This worked to re-supply you, whether you were in a "free mail" situation or back in the Japanese hospitals, where stamps were required. Also, there was enough leeway in the incoming postage weight to include two sticks of gum--three if they were Dentyne. Other NationalitiesOnly once did we see other troops beside us. We were on the line, but not in bunkers or foxholes, when an outfit of Turkish troops passed through our lines at night. We were given orders to relace our boots in a specific manner and to hold our fire. The Turks had been trained as night fighters, we were told, and the lacing job was how they identified friend from foes who had seized Army or Marine footgear. They were good! We did not know they were advancing through us until individuals were tapped on the ankle by the grinning Turks, who slithered on by in silence. South Koreans were our interpreters, guides, and liaison. At any time, we only had a handful with our company. I saw very little of Korean homes and children. We moved too frequently, and often by foot, over rugged hills where no villages existed. Sometimes Korean "porters" carried some equipment, food, and ammo loads for us. Once, we hired some laundry done. A few orphan Korean boys found odd job work around the troops when we were in reserve. Enemy TroopsActions in which I participated were at distances or at night. In either case I could not tell age or fighting ability or any differences in how the enemy fought, except they were noisy, and did a lot of talking and yelling. Lacking radios, they gave commands by using bugles and whistles at night, but were silent during the day. The exception to this was one lone enemy soldier who in March, when we were temporarily stalled, greeted the morning with a howling cry. Of course, he was labeled "Tarzan." Many of our enemy had U.S. weapons taken from Army and Korean outfits they had defeated. Their concussion grenades, however, were not as good as our fragmentation grenades. You could survive close explosions, as many of our men found out. The only time I saw the enemy up close was dead. They were clothed in tennis shoes, baggy uniforms, and quilted jackets. In ReserveThough there was a war going on, we followed a "normal" routine whenever circumstances allowed. In Reserve, we opened our mail. Some men got unwelcome items from home in the form of "Dear John" letters from girlfriends. It made them pretty sad. Because there were no atheists in our foxholes, many of us attended Sunday services (outdoors). We joked a lot, had some volleyball games, played horseshoes, and, in July and August we occasionally went swimming. I had smoked before entering the service, so in Korea I smoked C-ration cigarettes. I drank my beer ration only, and played some penny-ante poker. Once I went with a friend to visit with his buddy in 5th Marines and ran into a hometown Marine from the high school class one year ahead of me. When we were fighting on the lines, we did not have the options to formulate opinions on decisions of military and political superiors. The line Marine's world was rather constricted. You knew your job, knew the few people on either side of you, your immediate superior, his superior, and your unit commander. You had a place to be and orders to follow. We did have strong feelings, but they were transitory, being mostly about daily miseries of cold, hunger, and hardship. Only when you were in reserve was there time to get introspective about why this and why that. At other times, we had to be 100 percent alert for daily dangers of ambush, evidence of enemy activity, odd behavior of civilians, etc. Overlooking such things could kill you and your unit. On the Front LineWe moved in fits and spurts as the enemy was driven back. During 74 days of "Operation Killer" and then "Operation Ripper", our forces moved north. Our job was to trade punches with the enemy, chasing to keep them on retreat, and holding fast when they resisted. We were to try to pin the enemy troops and call in artillery or air strikes. We marched to take a hill, they skirmished, and then they disappeared. We received a Presidential Unit Citation with two stars for the 74-day battle to the north in the spring of 1951. History books say that we were attempting to inflict as much hurt as we could on enemy troops, overrun their supplies, and keep them moving defensively rearward. Everything we did was within the possibilities created by our training and physical conditioning. We were always guarded by sentries. We were always prepared, with fields of fire for machineguns and riflemen pre-determined. Foxholes and/or bunkers were reclaimed or dug. (There were many holes all over the area, and some were "adopted" by the first group to find and inspect them. They saved digging.) Our bunkers were small, hastily built, and briefly used in 1951. They were furnished with shelter half covers and grenade holes. Although they were ditched to keep water out, we still were slightly damp and muddy in Spring 1951. They were generally rectangular, 3 to 4 feet deep, with log parapets covered by dirt. The tops were tent halves. Life in a foxhole differed from life in a bunker because the foxhole was for more transient movement -- dig 'em and leave 'em. Move up! Tanks could not be effectively deployed in the mountains of eastern Korea. They were confined to foothill fighting, but I know that they were supporting our return off Hill 902. We had fire support using other means, too. We had support from mortars quite frequently, and some from heavy artillery Most commonly, however, the most effective support was close air support. What we liked best was that F4U fighters were our "air cover" and they did a whale of a job, using .50 caliber machineguns, 20mm cannon, and napalm. They could see from above where the enemy was, and put some hurt on them. Fighting was generally in the daytime, probably because that's when one side or another was trying to seize real estate. Since we progressed slowly from reserve status to patrols, to pushing forward, and finally into pitched battle, I was not especially fearful until the night of April 23-24, 1951. Hill 902We had been in Reserve again, but before noon were told to saddle up and board trucks. Taken forward several miles across the Hwachon River, the trucks went as high on the foot of the mountains as the road allowed. We were hurried along a foot trail, and when the trail ran out, we climbed up and to the northeast all afternoon, with only brief stops to rest. It became apparent that we were in some kind of race, as our officers and noncoms urged us on. At 2000 that evening, we topped the hill and were swiftly assigned positions. Picture a fat-headed, wide top of a "T" and a long skinny stem--with the whole letter flopped over so you're standing on the head and the stem reaching north toward a huge dip in topography that reclimbs to the next, higher, mountain crest. We were not alone. Howe and Item Companies were given the crestlines to our left and right, but George Company took the middle, with men scattered from the foot of that skinny stem, which became our forward point, to the tip of 902. Five men were posted on the forward point. One machinegun was set up 30 to 40 yards behind them, covering the only usable access to the peak behind us. Marines were placed in existing outpost holes to left and right rear of the machinegun. The second .30 caliber machinegun was situated on a slightly-cupped ledge about 45 feet wide and perhaps 25 feet deep near the mountaintop. About 20 to 25 minutes after G-3-1 reached the top of Hill 902, the enemy arrived from the other side. Shouts and rifle fire, grenades bursting, and the booming of a .45 caliber pistol punctured the growing darkness. Our machine gunner, Danny Daniels, began firing, cutting down the advancing enemy and causing them to disperse to cover. "Speedy" Wilson came to my foxhole, 40 feet left of and on a side hill beside our machinegun, and ordered me back to the ledge, then accompanied me to ensure that I made it. By that time, the machinegun had also been ordered back and Danny and assistant gunner DeVries began firing from the ledge. When PFC C. W. Johnson came over the ledge from the right rear of our gun, an enemy bullet pierced his kneecap. Howe and Item were commanded to hold fire, so as to conceal the location of their supporting lines, but helped us greatly with supplies of grenades, our most effective defense. I moved my two ammo cans to within reach of our assistant gunner, then was told by Gunny Wilson to see that C. W. Johnson made it safely over the hilltop to where our aid station had been set up, then return. When I did so, coming back to the right rear of the gun, I was injured in the right hip and leg by the same hand grenade (we believe) that exploded its head (primer fuse) and shrapnel into (Californian) PFC George T. Jacobson's right shoulder and forehead. Again, Wilson was immediately there, and told me to take Jacobson back 12 feet or so, to the shelter of some stacked mortars and cover him, since "Jake" was unable to use his right arm to defend himself. At some time later, when grenades and mortars were thickest, we heard the sudden "thump" of one hitting a Marine and exploding. It was DeVries, who was struck in the lower back and killed. To this day I do not know whether I imagined, or really heard his low moan of "Mother" before he died. PFC Joe Faulk was creased on the top of the head by a bullet and temporarily paralyzed on one side, which lasted for weeks. PFC Marvin Ryan was drilled through the shoulder by a bullet. (Ryan was big--a 200-pounder.) TSgt Harold E. Wilson was hit several times by bullets and repeatedly struck by shrapnel. His right arm was hurt and his face bleeding. He continued encouraging his Marines, finding them grenades, ammo clips and holding morale high. He was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions that night. Corpsmen weren't bulletproof either. A Corpsman from one of the other platoons was shot through a shoulder, and continued treating Marines while HE in turn was being aided by "Doc" Leeson. One enemy crept almost into the first-aid station. Doc pounded on his head with an entrenching tool and thoroughly discouraged him, rolling him back downhill. During the fighting, the enemy came close enough to the ledge that they could jump and almost reach the tripod of our machinegun or a few rifle barrels too close to the ledge edge. Hand grenades bounced off the slope below the ledge helped dissuade these attempts. When they got clever and threw the grenades back, some Marines tied sleeping bag straps and shoelaces to the grenades, and tossed them outward, but the grenades never hit the ground. They exploded as they hung from the ledge and cleared the area immediately below us. Fighting continued all night, with machinegun and rifle bullets, mortar shells, grenades and a few rockets attempting to snuff G-3-1. Didn't happen. We gave back better and more directed fire than we received. That protective ledge sheltered us... and the bullets whizzing only feet above illustrated why Marines are taught to "keep your heads down." Later estimates place the attacking enemy strength at regiment size, and bodies visible after daylight April 24 indicate at least 300 enemy casualties were sustained. The enemy was not totally quelled, however, until about 0930-0945 April 24, when two F4U Corsairs swept up the back slope of 902, flipped over the top and fired machineguns and cannon, then moved past the forward point and dropped napalm tanks. That stopped the attack and allowed our dead to be recovered from the "stem." Then we began retiring from the mountain. Hale members of G-3-1 "leapfrogged" our machineguns behind us, and Howe and Item closed in with added firepower. We left, but had totally blunted the Spring CCF counteroffensive in our area. One of our Marines was taken prisoner on Hill 902. PFC Lantow, one of the five men on the forward point (Hill 902) described in (I think) a Leatherneck article titled, "God and a Grenade" how he was captured the night of April 23, 1951 and taken a short distance to the enemy's rear. He had not been searched, he stated, and while his captors were in a tight circle debating some point, tossed a grenade into their midst and took off downhill, leaping and rolling to the bottom of a ravine. He hid, and came back through the lines of another Company the next morning. There was not concern among us that we would be captured. Instead, we felt that WE were the ones pushing the enemy back north, and our capture seemed a slim likelihood. Casualties of 902I did not see any of our dead until April 24, on the back slope of Hill 902. I felt sorrow for the Marines who died and whose hopes and futures died with them. I had known two of them about five or six weeks, and both were good men. G-3-1 lost eight men on Hill 902 that night. One was PFC Paul DeVries from Tennessee, who was Assistant Gunner of my squad. He was struck in the small of the back by a grenade or mortar burst while feeding ammunition to the machinegun in the heat of battle. I knew PFC Arthur Danzer and PFC Joe Caruso, who also were killed that night. They were overrun in our forward position, and shot by the enemy. George Company was battered, but unbroken on that mountain. For instance, of 69 men in the 3rd Platoon, only 17 left Hill 902 unscathed. All others were struck by bullets and/or shrapnel, but many of those required only first-aid treatment, not hospitalization. Our wounds were cared for by the Navy corpsmen who were assigned to G-3-1. HM John Pennell and HA John Leeson were our Corpsmen. I do not remember which one of them worked on me, but they both were very, very capable. They were real jewels of care, patience, and understanding. We took these men into our hearts as brother Marines. They shared our risks, suffered under the same heat, cold, and enemy fire that we did, carried as much if not more gear, and literally plugged the holes in our bodies, in many instances saving our lives. I received grenade or mortar shrapnel wounds in my left foot and leg on Hill 902, as well as a few more pieces in my right hip and leg. The most severe, however, were the dozen or more small pieces of grenade or mortar that tore through my left shoe in a dime-sized cluster, and a couple of "strays" just below my anklebone. Because of this wound, I could crawl or limp, but not walk or run. As a very active youth, I had skinned and scraped parts of me, broken an arm a couple of times, and still carry a .22 rifle slug in my leg from a teenage hunting accident. So I knew about being hurt and how it felt. I could estimate about how bad my injury was. However, I did err in assessing WHICH wound was more serious. Due to the intense fighting, I could do nothing until morning. After two Corsairs drove back the attacking enemy, I crept over the hilltop just in front of Speedy Wilson. Either Corpsman Pennell or Corpsman Leeson then gave me first aid, counted my holes, and gave me a shot. By then, my left boondocker was soggy with blood, and the green sock that I wore was bright red. Stretcher-bearers came to the backside of the tip of Hill 902, where the wounded had been gathered, and loaded non-walkers onto canvas litters. I remember to this day lying on the stretcher more than an hour, waiting for the return trip to start, while facing the stumps of a dead Marine's legs. A mortar or grenade had blown them off, killing him. Stretcher-bearers took me to the road end where we'd begun our morning-before climb. My stretcher was loaded on a tank top when we reached the bottom of the trail. Upon being hauled out of the danger area by the tanks, I was taken to an open site where a helicopter could land. We sorely wounded were quickly bandaged and popped into stretcher cages, one on each strut, under a helicopter. We were flown to Taegu, where there was a large Army hospital. By that time I was sedated and unable to enjoy the view, being out like a light. From Taegu, I went via a hospital plane (stripped for bunk space) to Osaka Army Hospital in Japan. From there it was off again, ending up at Yokosuka Naval Hospital. I spent the next three months recovering from my wounds. I was a patient in the Yokosuka Naval Hospital in Japan, and the Hospital Annex at Otsu. My 20th birthday took place while I was in Yokosuka Hospital in 1951. My wounds were cleaned and treated. Bandages on my foot were medicated compresses for 5-6 weeks. Most of the shrapnel, though, is still with me. Doctors determined that more harm would be done by probing for them all, than by letting the bits become "encapsulated" by my body. (My shrapnel is still with me today, and I have had no problems with it yet.) Within days I had relived the experience. I was deeply appreciative that T/Sgt Wilson had returned to my position on Hill 902 and ordered me back to the ledge. If he had not done so, I am convinced that I would very quickly have been overrun by the enemy. I didn't "miss" my buddies, as about a third of the 3rd Section machine gunners were there at Yokosuka hospital, in another ward down the hall. My parents received a telegram about my injuries. My father later told me how he had received the telegram. It was the second telegram my parents had received from the "GOVT, WASHINGTON, DC." The first message had given them the terrible news of my next-older brother's death in World War II on Leyte Island--the only one of many Keizer cousins who fought in World War II who was slain. HOW my telegram was delivered illustrates the warmth and caring of a small town. The CNW Station Master (and father of one of my classmates) who was also the telegrapher, and who had borne the first telegram, hand-carried "War Dept. Message #2" four blocks to my father's business. He would not, however, give it to my father until he had repeated several times the facts that, "Milt has only been wounded, and is now safely in the hospital. ONLY wounded." Every time I think back to that act of kindness, I get tears in my eyes. Joseph "Bo" Faulk was semi-paralyzed, due to his skull being creased by a bullet. He was a lightweight southern boy who had a good sense of humor. In order to get through the swinging doors to the Ward toilets at the hospital, he needed two-man intern help or a wheelchair. One day about four weeks into May, Faulk had to go to the toilet and no chair or interns were available. I laid down my crutches and another Marine and I used our "good" sides to assist "Bo" through the swinging doors. As we got him in there, a Ward nurse spied us and came hurrying down the aisle, scolding all the way, so we dumped Faulk onto the toilet seat and left...while his nurse fumed, "Who's going to help me get him out of there?!" We told her to be sure to wash her hands...

At Yokosuka Hospital, the Salvation Army "Grey Ladies" were very nice, friendly and helpful. They brought reading materials and stationery to the patients and helped them with letters. I thought the Red Cross girls I saw there were real snots. They spent little time helping any patients I knew and were said to charge for writing letters a patient could not. I wrote a letter to my parents from the hospital in Japan. I'm sure they replied and I got their letter, but all of my personal belongings, including mail, were burned in a fire at East Medical Unit where I was in late November/early December 1951. During my recovery, I was allowed liberty from the hospital. I sailed a catboat on Lake Biwa twice on weekends. Jerry Henjum, who signed up with the Marines at Sioux Falls, South Dakota the same day I did and with whom I went through "Boot", joined me. He had an arm wound and I a foot wound, so it took two of us working together to handle the small boat. Exactly three months from when I was wounded, I returned to Korea. I was flown from Japan to Korea and then moved by truck to rejoin George Company on July 23, 1951. I wanted to get back to the outfit, as did PFC William Cranfill Sr., a 5th Squad machinegun member, who returned with me on the same plane. I also had no choice as to whether I would go back to Korea or not, even though I was quite willing. I had only one Purple Heart and had only been in Korea a couple months before being wounded, so I did not meet the USMC requirements for "rotation." I had too few points, too little time in country, and only one wound taken in action (we needed two major ones). So back to the war I went. Back to the Front

When I got back to G-3-1, I found that it had only moved a few miles from where I had left them. They were "In Battalion Reserve" a while, cleaning and repairing gear, and getting replacements for losses suffered in early June battles. We did a "night problem" wherein we practiced taking a crest of a low mountain (in pouring rain), making camp and "digging in" as though we were staying. In a day or two, we moved back of the lines once more and this time went into "Corps Reserve" for about two weeks. Our only dangerous day then was when the ROK were trying out a new firing range and a few of their bullets came ricocheting over a low hill and through the tops of some of our six-man tents. Ammo was drawn, as it was assumed we were under some sniping attack, and we skirmished up the hill. Words were exchanged between our superiors and the ROK officers. The "firing range" was re-oriented, immediately! This ended the shooting war for me. In mid-August I was transferred to First Marine Support, and shortly thereafter, George Company came out of Reserve status to go to "Starvation Hill", about which I have heard, but have no firsthand information. I left George Company on 13 August 1951, and was sent by truck to the 1st Service Battalion. I was going "to the rear with the gear," an euphemism for relative safety, and was glad of it. But I still felt that I could help my buddies by what I did next. Believe me, I sure knew what a morale boost a Marine got from a hot shower and clean clothes!

Marine SupportMy assignment with First Marine Support was at the 1st Marine Service Battalion in, specifically, a laundry and shower group. This was from September 1951 through the middle of February 1952. My tasks were to maintain and repair large laundry washers and dryers, set up showers and boilers, place and service hydraulic pumps that drew river water, and to help sort and wash dirty clothes. Marine units would come to our area for a few days of "reserve." We had stacks of clean dungarees and underwear and hot showers. Marines got their first good shower bath in weeks, traded grungy garb for clean, fresh clothes, ate well at the nearest Mess Tent, and went back to the line refreshed, healthier, and feeling/looking good. It was at this location that I was injured in Korea from something other than the enemy. I do not recall the Marine's name, but I heard of a "short-timer," soon to go home via rotation, who was accidentally killed by being crushed between two trucks while returning to G-3-1 from a medical treatment. I did not have that kind of worry, although I was injured about the time I was scheduled to rotate home. I sustained a hand injury at the 1st Service Battalion's Laundry outfit on December 17, 1951. While repairing a large, belt-driven washing machine, I asked the operator what it had been doing before it

quit. He turned it on without warning to show me, and my left hand was caught in the belts and rollers, mashing

the two middle fingers and breaking my forefinger. When I managed to free it, the forefinger's middle knuckle was

broken so severely that I could hold my hand horizontal, pointing to the right in front of my body, but the finger

also made a right angle, pointing to my chest. Doctors in Korea could not repair it, so after a few weeks of "A"

Med. and "E" Med check-ups, I was sent to Yokosuka again. After splinting, "rehab" exercises, and some recovery,

doctors there then checked my service record and found I was so close to "rotation" status that they put me on the

next "USS Repose" homebound hospital list. Going HomeI went by truck to a medical unit, and then went by truck to Pusan. From Pusan I boarded an airplane to Itami airport in Japan. I took a truck or military bus to Yokosuka Hospital. The doctor who was treating my hand at Yokosuka told me to "pack up and stand by" for a return trip to the States aboard the hospital ship "Repose." A military bus took me to catch the hospital ship. At Yokosuka, I was given a half-issue of clothing to replace that which burned in the "E" Med Unit fire. My stored sea bag was located and returned a few days before I boarded the ship and I climbed the boarding ladder with it, along with the rest of a hospital contingent. The Repose transported injured Marines being sent to U.S. hospitals, plus some rotatees going home for discharge or reassignment. The sailing time to the U.S. was approximately 15 days. During that time, I came down with a case of "crabs." It is believed they came from Navy life jackets that everyone was using as pillows and seats on the deck. I was tired. Then relaxed. Then bored. And I was glad to be heading for the United States. I watched a couple of very old movies, and played card games. We hailed another ship halfway home and traded by breeches buoy two movie films and some mail, but their films were even older! The ship's store had some paperbacks for sale, plus you could buy ice cream and cokes at five cents each. The ship's store was open for four hours each weekday. The weather was okay with the exception of a couple of rough days. Only a handful of Marines got seasick. The ship stopped at Hawaii, but I stayed aboard as I'd bought a bamboo fly rod for myself and some family gifts in Japan while at the hospital, and was nearly broke until the next payday. We landed in the States on 15 February 1952, one year from the day I had first shipped out to Korea. By luck of the draw for hammocks, I had slept in a different area of the ship than the rest of the hospital group. Once, I thought I heard my name called on the ship's speaker system, but wasn't sure, so I didn't check. (It could have been KP duty of some kind!) Whoever was in charge of the "walking wounded" didn't look very hard or repeat the call, so I never got an order to stay aboard ship when it stopped at San Diego. The injured Marines and I were supposed to go on to San Francisco, but I didn't know that. When I left the ship, the United States of America looked good, smelled good, and felt good. Everyone aboard sucked in some clean, healthy U.S. air. I stood in line on the deck and was issued my sea bag from the ship's hold. I shouldered the bag and walked down the gangplank to board the military buses. I looked around for my hospital group, but did not see them again -- ever! They had stayed aboard the ship to continue on to San Francisco and the Navy Hospital there. I had debarked at the wrong place! I was taken to the MCRD at San Diego. At MCRD, long lines formed on the Parade Field, facing about eight big signs having letters of the alphabet on them. Since I saw no Marines wearing casts, slings, or bandages, I knew something was wrong. I approached a Warrant Officer, saluted him, and said, "Sir, request permission to speak to the officer." Given that, I said, "Sir, I don't think I should be here." The Old Corps salt advised me, "Son, if you weren't supposed to be here, you wouldn't be here, so form up in your line." I did. The WO and I, and one Sergeant who had a clipboard and stood at the J-K-L sign, were the last three Marines on that Parade Field. The Warrant Officer asked my name and I gave it again. He then asked the Sergeant if I was on his list. Told "No" by the Sergeant, without changing his expression the WO looked me straight in the eyes and said, "Son, I don't believe you're supposed to be here." He then ordered the Sergeant, "Determine where this Marine belongs. Find something for him to do while you're looking." So, for the next five days I became a runner who delivered separation papers and other orders to batches of Marines who were enjoying Liberty Call and making plans to head home. Me? Remember that I was broke and had no records to show when I was last paid and to which place I was supposed to have been shipped. I had NO off base liberty until they located my hospital records at the San Francisco Navy Hospital. Then I could draw pay and on 29 February 1952 start a 30-day leave of absence, going home to Iowa. It was an unusually early spring, mid-afternoon, and I sat under a warm sun on the rear railing of the caboose as we rolled through the Missouri Valley, heading toward Sioux City. I sucked in the lush air, the green, growing smells of the field, and knew that I was truly "home." I'd told no one when I was coming, arrived in late afternoon at the train station and shouldered my sea bag to savor the walk home--about 1 1/4 miles through familiar small-town streets. My mother had barely begun preparing supper when I walked in and asked, "Do you feed hungry strangers here?" She did. Post-Military LifeAfter leave, I returned to my previous duty station of Hawthorne, Nevada, for discharge. That took place on April 4, 1952. I did not consider re-enlisting. I had begun at the State University of Iowa, and was determined to continue. I joke that I never received the rehabilitation course or lecture, but I went back into civilian life quickly and easily. I point out that this might have been because I was in service for a year before the Korean War, out for four months, called back for another 18 months, then discharged again. It was easier for me to adjust than, say, someone who was drafted and went from Boot Camp to battle. I operated a truck-mounted trench hoe and drove a pit gravel truck for a few months after my discharge, and then I resumed my studies at State University. After three years, my G.I. benefits were nearly exhausted. I had only 19 days of school time left. Having married on September 5, 1954 between second and third year a young lady one class ahead of me and momentarily expecting our first child (born 10 days after my wife got her BA), it was necessary for me to find a job to support my family. I had met Joelle Wahl of Council Bluffs, Iowa on a "blind date" originated by the roommate of a hometown friend. He wanted to take HIS hometown girlfriend canoeing and wanted company, and would I find someone and go with him? I called Russell House, a girl's boarding dormitory where a female friend from my hometown resided, and asked for her. The young lady who answered called out Mary's name...no answer! So I asked for Ann, another young lady whom I had met when a handful of male students had talked with their Steering Committee about starting a men's boarding dorm, but she too was not there. A third try was for Marge, a girl who visited my hometown friend for a week and who shared a picnic with a bunch of us...nope, she was not there either. So I pled my case with the one who WAS there,,,she who answered. To make a long and further convoluted tale shorter, a "Coke Date" (read "inspection") was arranged and, when I went to Russell House and called her name and saw her...I said to myself. "This one could be the right one for me." A year later we married. I went to work for Link-Belt Speeder Company in Cedar Rapids, IA, just "26 miles, 52 curves" away from SUI, hoping to return in a few years for my degree. Twelve years later, with four children, we returned from seven years spent in Woodstock, Ontario as Manager, Canadian Parts Operations, Link-Belt Speeder (Canada) Ltd., and went directly to Iowa City, where I graduated in June 1968 with a BA in Journalism, Magazine Sequence. Our children are Colin Roy (1955), Robin Lee (1956), Lance Ellwood (1958), and Wendy Rae (1960). During the years 1955 to 1967, I went from a painter in the shop at Link-Belt Speeder to Parts Editor, to Manager, Canadian Parts Operations. Then I returned to finish my final year at SUI. I believe that I had more awareness than my fellow students of how mortal we are and how quickly life can stop. Serving with Marines from all over the USA taught me every man's contribution counted, however humble the task. It also showed me how close to death all men are: not only a bullet, but perhaps a blood clot, or extreme cold, can kill you. Also, I remembered more clearly than some University of Iowa students the beginning of World War II--where I was, when we heard the news, how I was told, etc. In stark contrast, at the University of Iowa in 1968, while auditing a class taught by James Briggs of "Better Homes & Gardens" magazine, a Des Moines, IA publication, we were discussing the "when" of news occurring. A young male graduate student asserted Sunday mornings were the least newsworthy. When I asked if he included Sunday morning, December 7, 1941 in that category, he looked puzzled and inquired what had happened then? Mr. Briggs quickly jumped on the question, warning me, "Do NOT tell him, Mr. Keizer." He told the student, "You WILL look that up!" After receiving a Bachelor of Arts/Magazine Journalism degree in June of 1968, I was in the Journalism field

from 1969 to 1998. I was a reporter, copy writer, author of five books, and editor. I was Editor/Writer of

an outdoor newspaper page. November 1998 was my last month of work. I co-founded, with John Thomas and Terry

Sheely, the magazines "Fishing Maps & Such" and "Washington Fishing Holes." I compiled and wrote the "Hunter

Education Manual" for Outdoor Empire Publishing. I wrote "The Fishing Holes Complete Handbook on Steelhead

Fishing" and "Western Steelhead Fishing Guide" books. I wrote and edited "Henning's Washington Fishing

Guide" and copy-edited and compiled "Henning's GUIDE to Boat Ramps." I also did editing or proofreading in

"Northwest Bass and Panfish Guide" and "How to Fish WASHINGTON Handbook" and "The Complete Handbook on

Washington's Clams/Crabs/Shellfish" and have written a hundred or more outdoor articles, mostly about fishing. In my retirement I read a lot, take gratis digital photos and do proofreading for a monthly community brochure, and fish a little. I spend a pile of time on E-mail. I was the Secretary for the G-3-1 Korea Association for two years. I am a past commander of an American Legion Post, but am now no longer active due to moving to a different town. Final ReflectionsFor me personally, the hardest thing about being in Korea was lack of family interaction. We visited a lot as I was growing up. My father had ten brothers and sisters, and my mother had two brothers and a sister, so we visited kinfolk frequently and had some great picnics and family meals. I missed that in Korea. I remember Korea from my first impressions to my last ones. My strongest memories are of the cold, heat, mud, mountains, and of trees mostly having been shot to shreds. I also remember that it scared the hell out of me when MacArthur talked of A-bombing and invading China. I wasn't alone. Many of us said at the time of Ol "Dug-out Doug," HE is going to get us in more trouble than WE can get him out of." My perception of a hero is someone who does his job exceedingly well, in the face of and despite danger and risk of death. Yes, I got a Purple Heart for the wounds I incurred on April 23-24--but, hey- almost EVERYONE in G-3-1 had one or more Purple Hearts and other medals. Receiving it was no big deal. I was recalled. I went. I fought. My unit was a team in which I did my share, and I survived a major battle (Hill 902) in the platoon of and because of a "Marine's Marine," T/Sgt Harold E. Wilson MOH. That will stay in my heart for as long as I live. I think that, as part of the United Nations, we were committed to defend against aggressive attacks by one nation against another, so it was right that the United States sent troops to Korea. I believe that if we had not fought the war in Korea, all Asia would have been Communist. Thus far, there have been 52 years of freedom for the South Korean people, and the Communist expansion into the rest of Asia was halted. I do think that MacArthur should have gone north of the 38th parallel, but only to establish a reasonable and very secure margin of safety for the 38th parallel. Pushing to the Yalu River was a slap in the teeth of the Chinese "dragon." Since North Korea has the fourth largest standing army in the world and covets South Korea, if the U.S. forces were to leave, I have no doubt that the North would strike again. I have never revisited Korea, but I would like to stand once again on Hill 902, where the all-night battle erupted so late in the day that darkness began to lock my view as the enemy attacked. I was so busy preserving my life and defending my small bit of territory that I did not see the rest of the battlefield. I'd like to stand on it again, just to confirm in my mind that I correctly understood the lay of the land and the sequence of events. Through the years, I have searched for my G-3-1 buddies. I wrote in early 1993 to Marine Bill Simpson, in response to an ad he had placed in the LEGION or VFW magazine, seeking a reunion with some of his G-3-1 buddies from the Korean War. He wrote back, advising there was no organized reunion he knew of, and that he was looking for specific friends. However, he said he'd let me know if he heard of any news of a bigger reunion, Only a few months later, Simpson phoned, advising there was a reunion group and it was going to meet in Seattle in September 1993 and I had better call the group's Secretary and get aboard. I called, and very soon thereafter, "CW" Johnson, an ammo carrier in the same squad I served, called me. He had found a couple more 5th Squad MG crew...did I know where any more were? Sort of. I recalled another member had enlisted from Kansas City, and that his parents had sent him a clipping about the 1951 floods there. So I sent four letters to four former schoolmates who lived outside the four corners of Kansas City, asking them to search their phone books for "William Cranfill" and to call to see if he was a Marine veteran of the Korean War and if he knew Milt Keizer. One girl made one call...BINGO! A high school locker-neighbor, Doris, found him and he asked her, "The same Milt Keizer who would use the word 'indubitably?'" Oh yes, she knew from the question that he knew me! He found 6th MG Squad member Ken Listerman. Only one member of the April 1951 5th Squad MGs whom we knew survived Korea could not be found. We all searched for years, using phone lists, Internet name-finders, fellow Marines and friends who could help. He was from Long Beach, California, and was discharged at Treasure Island in spring of 1952. Many years later, I received the sad news from a Marine, via a Marine bulletin board, that our buddy Pfc. George Jacobson had died in 1978 in San Francisco, before we began looking for him. "CW" has passed away also, and Bill Cranfill, Mark Parkin, Jack "Danny" Daniels, and I now are the last four survivors of G-3-1's April 1951 5th Squad MGs. I try to attend annual G-3-1 Korea Association reunions held in different parts of the country. These Marines, both U.S. and British, and their ladies have become extended family because of what we shared and mutually remember. Too many times, history has been rewritten by what I call do-gooders who would, as one museum actually did, blame the United States for "causing" the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and their atrocities and savagery, and who decried the use of the Atomic Bombs that forced the end of World War II and thus saved the lives of three-fourths to a million Americans and perhaps 6 to 10 million Japanese. If some student finds a copy of this interview someday, I would want that student to know that the Korean War was a mean, dirty, bitterly cold, stinking hot war that no one liked... but it was also necessary. After the war was over, Korean War veterans came home and melted into jobs, homes and schools and got on with our lives in a country tired of wars. Because of that, the Korean War carries the title, "The Forgotten War." I believe that World War II veterans were more visible, and more thanked because of their longer individual service in saving a world from peril. Those of us who served in Korea rescued one land. I do feel, though, that you can be just as dead if killed in a "Police Action" as a World War. Once a MarineThe Marine Corps teaches duty, honor, respect, pride, and a commitment that stays with you. There is a discipline ingrained in Marines from "Basic" to Honorable Discharge that you can draw upon to overcome civilian "battles" too. You do not fail to salute our country's flag, never forget to snap straight at "Ten-hut!" or to square your shoulders when "The Marines Hymn" is played. You didn't buy it, weren't given it as a gift. You EARNED the title of Marine, and can wear it in pride and honor. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||