|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||

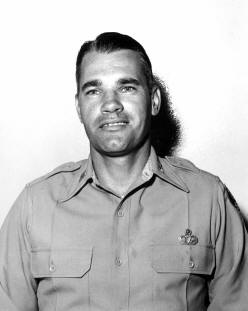

Col. Robert Ellis JonesClarksville, TN - "The Marines gave very little recognition to the Army's significance at the Chosin Reservoir. They still don't. However, the Marines finally agreed to recognize the Army and give them the Presidential Unit Citation that they received for the whole operation. They finally acknowledged the importance of the Army element that was east of Chosin." - Robert Jones

|

|||||||||||||||