|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||

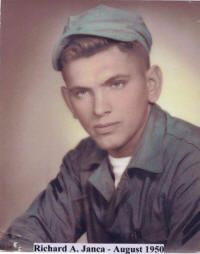

Richard Antoni JancaOrchard Park, NY - "It was dark as I moved my unit below a ridge line with orders to dig in. Enemy shells were falling, looking for a target. I broke out my shovel, dug my hole, and tried to make myself comfortable. Shells were still seeking victims as I crawled into my sleeping bag. Shortly I could feel something crawling all over me. I tried not to panic as a colony of large ants invaded my sleeping bag, causing me great discomfort. My hair, face, and body inside my clothing was covered with ants. I could feel them crawling all over me, leaving me no choice but to vacate my foxhole, pull all my gear out, and shed my clothing to try to cleanse all the ants from my body and clothes." - Richard A. Janca |

|||||||||||||||

Memoir Contents:

Chosin Reservoir:

|

|||||||||||||||

KOREA

September 1950 - September 1951

W-2-7 1st Marine Division

San Diego, California. September, 1950

"It’s early morning and it looks like we're in for another beautiful warm summer day. It’s also a special day for me; in a few more hours I'll be embarking on the greatest adventure of my life. There is a war taking place in South Korea with a Marine Brigade already actively engaged since early August helping to stem the tide of a communist take over. I've come a long way since I left home in January of 1948."

Background Information

I was born Richard Antoni Janca, the middle child of Joseph and Julia Zynczak Janca, on July 5, 1929 in Lackawanna, New York during the year of the great stock market crash. My father worked as a coalminer in Shenandoah, Pennsylvania after emigrating to the United States from Poland. Thereafter, he moved to Western New York upon hearing about the plentiful jobs in Lackawanna at Bethlehem Steel Plant. My mother was born in Lackawanna and was a war defense plant worker at Trico, in Buffalo, New York. My parents met and later married, then built a home at 100 Elkhart Street in Lackawanna, where all their children were born. I had an older brother, Edward, and a younger brother, Michael.

Lackawanna, known as the Steel City, got the nickname from a major steel-making corporation. Bethlehem Steel, the largest employer of labor in the area. I grew up with the Depression generation and all the hardships that came with it. Those were tough times, but they also taught one how to survive on the barest necessities in life. It was nothing compared to what Marine veterans of the Pacific War in my unit had endured. They not only had to deal with the enemy in combat, but also exposure to nature. The hot, infested jungle with its panoramic assortment of disease plagued many of the veterans that were still around. Not long ago on a rifle range, I watched as a Pacific War veteran came down with a malaria attack. His canteen cup and hands shook so badly that he needed assistance to hold and drink from it.

I attended St. Michael's Catholic School and Washington Elementary School, and then I entered Lackawanna High School, from which I graduated in 1947. Like my father and brother before me, I applied for work at the local steel mill (Bethlehem Steel). I was hired immediately and was assigned as a laborer in the powerhouse. This would only be a temporary job until fall, when I would return to school to further my education and hopefully upon completion of study find a better paying position. I almost didn't make it. One night while at work I was assigned to a work detail, shoveling dirt out of a boiler. I can't remember what happened, except I woke up in the medical building lying on a cot. I asked, "What happened and how did I got here?" I was told I had collapsed while working and was brought to the hospital for medical treatment. I was overcome from gases that were still present in the boiler and was fortunate that I wasn't alone. The other workers saved me from what could have been a major disaster. This job had almost cost me my life so I decided to enroll at Erie Community College.

In the fall I was a full-time student attending Erie Community College, taking a course in mechanical technology. The school was located roughly ten miles from home. Since I had no wheels of my own, I had to commute to school by bus. I had a rather long school day, so I would on occasion stop at Kogut's Tavern, a local gin mill and a regular hangout for most of my friends. It was shortly after the start of my second semester that I dropped in at the tavern for a drink and to chitchat with my friends. On this particular night I happened to arrive as a drinking party was taking place and I was invited to join them. There were six or seven in the group and all were hyped up about joining the service. In the group were recent Army and Navy veterans who wanted to try a tour of duty in the Marine Corps. With beer flowing freely and time slipping by, my friends convinced me it was time for me to leave home, do some traveling, and get to see some of the world I lived in. I agreed to join them the following morning at the local recruiting office. Needless to say, only three of us showed; the others either drank too much or had no intent to make a firm commitment when sober.

The next morning at the recruiting office, a Marine NCO extended a warm welcome, asking if we wanted to enlist. We came to enlist, so he filled out all the necessary paperwork and had us sign our names to a three-year enlistment. Now all that was left was a physical scheduled for January 15, 1948, with departure to take place that same night if we were fit for duty. We were all accepted. Henry Martin Bodziak, a classmate of mine at Lackawanna high school and I went to Parris Island for boot training, while John Pluta, my neighbor who lived three doors away and was an Army veteran, was issued orders to Quantico, Virginia. At a later date I learned that some of my friends who originally chickened out in joining the Marines with us had eventually wound up entering other branches of the military.

Training Camps

Boot Camp

I remember my boot camp training days at Parris Island, South Carolina where discipline was taught in a punishing manner. I can still recall the day our Drill Instructor wouldn’t excuse anyone to make a nature call. This resulted in an epidemic of pants wetting when a boot couldn’t hold back any longer. Another time we ran the obstacle course and then double-timed all the way back to our barracks. The DI then asked if there was anyone that still had the energy to run some more. Three others and I remained in the ranks when the order was given to fall out. We were then instructed to run up and down the Company Street. After considerable time elapsed the DI came out and terminated our marathon. Once inside the barracks, our failure to admit fatigue resulted in demeaning punishment. We were ordered to get our buckets loaded with soap and water and then were told to scrub the barracks floor with a toothbrush. Discipline was a key to success and the Marines were good at that.

After graduating from Parris Island, I went to Camp LeJeune and attended Sea School. I applied to go to the Annapolis Naval Academy but the paperwork got lost and I was given different orders and assigned to the aircraft carrier USS Leyte CV32. I spent a two-year tour of duty aboard that aircraft carrier with the Sixth Fleet in the Atlantic Ocean, including one week aboard a destroyer during an amphibious training exercise against the island of Crete in the Mediterranean Sea. A guy named Harry Griswald and I became good friends while serving on the ship. At the end of our tour of duty on the Leyte, Harry and I received our transfer orders off the carrier on the same day. Our new destination: Camp Lejeune, North Carolina.

Camp Lejeune

On arrival at camp, Harry was assigned to the 2nd Marine Regiment; I was placed in the 6th Regiment, Weapons company, 2nd Battalion. On reporting to my company, I was given a choice of 81 mm mortars, heavy machine-guns or anti tank platoon. Why I chose anti-tanks I can't recall. I soon learned that this platoon handled 3.5 rocket launchers, flamethrowers, demolitions, and, later, light machine-guns. Our platoon ran field exercises for reservist who came to camp for their annual two-week drill. In turn, we staged a lively show, attacking bunkers using flamethrowers and demolitions while our guests observed from bleachers on the sideline. Little did we realize while staging these exercises that a war was brewing and ready to erupt in South Korea. All these exercises were a training asset for all Marines involved in preparation for a real confrontation about to happen.

War Breaks Out

On June 26, 1950, we were informed at a special troop formation that North Korea had invaded South Korea during the night. There was no mention that America would be involved. My enlistment was to be up on January 14, 1951, but my "short-timer" status was shattered by Harry Truman's decree to extend my tour of duty one additional year. I had only had one ten-day leave since my enlistment, and that was time I spent at home at completion of boot camp. I had accrued a sizeable chunk of leave time, so I applied for a thirty-day furlough. It was approved and my leave began on July 19, 1950. I came home from Camp Lejeune by train with a return ticket to use when my leave ended.

I had been home a few days enjoying myself when a special telegram arrived ordering me back to Camp Lejeune immediately. That telegram changed my leave plans. I decided to spend an extra day at home, then book air passage back to D.C., returning the rest of the way by rail. It was at the D.C. train depot that I bumped into my old shipmate Harry, whom I hadn't seen since our arrival at camp. He told me that he was newly married and was on his honeymoon having a great time when his telegram arrived, spoiling what time he had left of his leave. We rode back together, reminiscing about our good old days aboard ship.

Our arrival at Camp Lejeune had a few surprises in store for us. Harry Griswold's regiment had departed for California, with most of my regiment in tow. My battalion, I believe, was all that remained at Camp Lejeune, along with some headquarters personnel. With his original company gone, Harry needed a home, so he was assigned to Weapons Company. It was just like old times being together again. I was placed on work detail, boxing equipment, and supplies on railroad cars for shipment to California. In the next few days Marine replacements began to arrive from duty stations throughout the country. Rifle companies were reformed and the Sixth Marines received orders to relocate to Camp Pendleton, California.

Camp Pendleton

We made the trip to California by train. I remember stopping at El Paso, Texas. This was the only stop where we had a chance to get off the train to stretch and exercise. The temperature didn't help. It was just too hot. Shortly after our arrival at Pendleton there was a change in regimental colors. We then became part of the Seventh Marine Regiment assigned to the 1st Marine Division. Our company and battalion remained the same.

It was a pleasant change of climate in California. At Camp Lejeune the weather had been hot and humid, and more than one shower a day was normal to cool us off. What made it stickier and more unbearable was the lack of air conditioning. That kind of comfort just wasn’t around in any barracks. At Camp Pendleton it got hot during the day, with showers taken in an outdoor facility. The mountain air cooled off so much in the evening that we needed blankets to keep warm at night.

Our time at camp was spent training for duty overseas. Classes in Judo were overseen by John Ivers, a black belt holder. Demolition usage was held in the classroom and then actual testing was conducted in the hills. I can still recall a charge I assembled with my instructor observing. I tossed my explosive device and waited. Nothing happened. That’s when my instructor told me to move my butt and retrieve it. I was in the process of rising off the ground when the instructor’s hand pulled me back down to the ground. He said, "Wait a minute longer." Just then the charge exploded. The temporary delay saved me from what could have been a tragic accident if I had gone to recover the charge when first told.

During our classroom sessions the instructors went out of their way to highlight dangers involved working with explosives, citing cases of injury or death resulting from careless handling of explosive material. After my near miss, I was in total agreement with their presentation.

Weekend Pass

During our short stay in sunny California, Harry and I got a weekend pass and we decided to make the most of it. We thumbed a ride to Los Angeles with our goal to see Hollywood. It was a Saturday night. We checked into a hotel with a tour of Hollywood planned for the next day. In the bar we met two girls from Texas who were on a holiday away from home. One girl was married. The other one came along to keep her company and out of trouble. We had a pleasant evening.

The next morning after breakfast we set out to see Hollywood. Thumbing a ride, a car stopped and gave us a lift. The driver asked where we were headed. After making our destination known, he said, "I know just the place where you want to go." All the time we spent in his car, the driver filled us in on what was taking place in town. His communication skill appeared like he was putting on an acting display for our benefit until we arrived at a tavern that the driver said would make our day. That trip was a novel experience for me. It was one that I shall never forget.

Inside was a hot band holding a Jam session. The place was mobbed and Harry and I were having a great time. I got introduced to a beautiful girl, with jet-black hair. Her name was Irene. As the hours and day ebbed away, Irene got real talkative and told me that she came to Hollywood hoping to become an actress, but being of Polish ancestry, felt that that may very well hinder her acting ambition. Later that evening she asked me if I would like to attend a late night house party at Al Jolson’s place, the famous singer. The people in the group she was with were all going, and Harry and I were asked to tag along. It was a tough decision to turn down her offer but we didn't have our own wheels and had to rely on being able to hitch a ride back to camp to make roll call in the morning. To this day, I've always wondered what I missed by not attending her party.

We never did see much of Hollywood. After leaving the tavern we walked over to a gas station to ask directions back to camp. The owner asked what part of the States we were from. When I said Buffalo, New York, the owner perked up and said he was also from Buffalo. This led to a friendly exchange and we got to meet some of his family. Later he gave us directions on how to find our way back to camp.

One day a photo session was held for all members in our company. Anyone interested had an opportunity to purchase a keepsake company picture or a large individual color photo. I ended up with one of each and had them mailed to my parent’s home. There was a night before our departure from camp that had Hoagy Carmichael down to entertain the troops, displaying his talent with a piano and songs he was famous for.

Just before leaving the States, Harry came over and told me he was given a transfer to Dog Company. His prior experience in a rifle company while with the 2nd Marines was responsible for the transfer. Word came to saddle up and I returned to my section, not realizing that I would never see Harry again. A chaplain was in the area chatting with the troops. I noticed quite a few Marines had stopped to ask questions, some pouring out their inner feelings and asking for the Lord’s protection, while others who had written letters now used the chaplain as the postman in handling their mail.

After two and a half years of duty I was now a Corporal assigned to Weapons Company, 2nd Battalion, 7th Regiment, 1st Marine Division. My duty assignment was to act as guide for elements of my company due to arrive from Camp Pendleton sometime that morning. I directed them to their quarters aboard the U.S.S. Bayfield, APA-33--a Navy transport that was waiting for their arrival.

Trip to Korea

Finally, with the troop arrival, there was activity taking place on the pier as American Red Cross workers prepared to greet Marines, handing out sewing kits, missalettes and copies of older magazines to anyone willing to accept them. While troops waited to go aboard ship, coffee and doughnuts were available to all that wanted to sample any of the freebies provided. A Marine band arrived just as troops started to go aboard ship. It was late in the afternoon with everyone on board. Our ship slowly started to leave port with the band still playing. "Harbor Lights” and “Goodnight Irene" echoed as Marines aboard ship joined in a final vocal rendition for a farewell to be remembered. The outline of San Diego slowly disappeared as daylight faded into darkness.

As mentioned earlier, I had spent a two-year tour of duty aboard an aircraft carrier with the Sixth Fleet in the Atlantic Ocean, including one week aboard a destroyer during an amphibious training exercise against the island of Crete, in the Mediterranean Sea. I was now looking forward to adding a new chapter to my list of world travels. This would be my first Pacific Ocean crossing, with a promise of new adventures waiting. Time would tell. Our destination was somewhere in northern Japan. There was a rumor going around that had us training in Japan for a few weeks, and then we were to join the 1st Marine Division in Korea.

To occupy our time aboard ship, a training schedule became a necessity. Many newly-activated reservists were assigned to our units, some joining our ranks less then a month ago with no prior boot camp training. Daily drills were held for their benefit on weapon nomenclature, taking firearms apart and reassembling. Our main support weapons were flamethrowers, 3.5 rocket launchers and demolitions. Every member in our unit had a designated assignment. One Marine was to carry a rocket launcher with other team members hauling rocket shells. Flamethrowers, being heavy, were to be hauled aboard a company vehicle until needed. This also applied to demolition equipment. Each man's assignment had to be interchangeable within the team in case a need arose.

With the schooling there also had to be some time for fun and games. We couldn't have a boring ocean crossing with all work and no games. What could be more entertaining than having a Marine aboard display his talent in hypnotism? He had an ample supply of candidates volunteering to be hypnotized. The entertainment came as his subjects were put to sleep and then our fun began; it was hilarious watching grown men succumb to sleep and then obey his commands. It felt like old McDonald's Farm had taken over our ship, with subjects under his spell portraying animals with sounds and gestures identical to animals his audience demanded. It wasn't a boring trip.

As we got closer to Japan, there was a change in weather conditions with typhoon turbulence causing pitching and rocking that resulted in many aboard becoming seasick. I was assigned a bunk in the bow area of the ship, where stormy seas were most evident. We had to ride out the storm and the best place for me I decided was in my bunk until the weather changed. Japan and Korea were the hardest hit by nature's fury during the height of this storm. On the morning of September 15, 1950, our P.A. system announced a successful landing of 1st Marine Division units at Inchon, Korea. This came as a surprise, since we were scheduled to arrive in Kobe, Japan that very day. Excitement spread through the ranks, giving rise to whether our plans would change as a result of this landing. A decision in change of orders was made upon docking. There were Marines waiting at Kobe for transportation to join the rest of the 1st Marine Division in Korea. It took thirty-six hours to square away our needs, and then we were back at sea.

On the morning of September 21, 1950, we arrived at Inchon with enemy targets ashore being shelled by a Navy task force that included cruisers and the battleship Missouri. I was on deck with other Marines scanning the shoreline, wondering what the future had in store for me. I wasn't the first or last in my family paying a visit to Korea. At the end of World War Two, my older brother spent a tour of duty with the army of occupation in Korea. Upon his return home, he told of the many problems experienced with natives who supported the communist movement. My younger brother, who enlisted in the U.S. Air Force, later also got his chance for a tour of duty in Korea.

Land of the Morning Calm

It was time to disembark. Our sea bags with all unnecessary clothing and personal possessions were to be left aboard ship. Each Marine wore his combat uniform with appropriate equipment, plus leggings. On the pier, trucks were waiting to take us to our prearranged assembly area. With all the troops aboard, the trucks moved out. It was late in the afternoon when we finally got to our designated area. Maps were checked to verify our location. It turned out that we had overshot our destination and were now way out into no man’s land. Our company officers held a discussion, deciding to march us back toward our designated battalion position. During our trek back, darkness took over. We were given orders to dig in for the night. As we dug our foxholes, word filtered down that Marines a short distance from our location had dug into a gravesite, their shovels making contact with bodies buried beneath the earth. This alerted everyone to use caution in his digging. I for one had no such experience.

During the night, as I watched from my foxhole, a firefight could be seen taking place quite a distance from where I sat. Tracers lit up the skyline while shell explosions echoed in the night. We were late for the original landing, missing all the fireworks. This was a preview of what we missed and what awaited us in the very near future.

The next day we relocated to a new position. It was still daylight when word came to dig in. Since it was early, it gave each pairing partner a chance to dig deeper foxholes. A shot rang out to my right; I dropped my shovel, grabbed my rifle, and waited to see what would occur next. Shortly, word came back that "Sergeant C", a Pacific war veteran, had shot himself in the foot while making a nature call. He was our first casualty, giving rise to questions whether it was accidental or intentional. Later that night all hell broke loose, as machine-gun and rifle fire opened up a few yards to my right. It lasted for a few minutes and ceased as quickly as it began. It turned out a Marine in a heavy machine-gun position had crawled out of his foxhole to make a nature call when someone with a itchy trigger finger let loose. This Marine did manage to make it back safely to his foxhole, but there was a lesson for everyone to learn and remember. Anyone moving at night was fair game to others around him.

The following morning we moved out to what looked like open terrain. There, we formed a skirmish line moving through the ground in front of us, not knowing what to expect. There was no enemy activity. We came to a road late in the afternoon. Up to then we carried our full packs and weapons. A short break took place and then we were told to drop our packs, but to be certain to carry our shovels. Our packs were to be placed aboard Jeeps and would be available to us later that night.

It was a warm day when we started, so even our field jackets were left behind. Whoever made this decision made a terrible mistake. We proceeded to climb a ridge, got to the top and stopped just before dark. That location was to be our home for the night without our field packs. The weather changed and the temperature dropped. The colder it got, the more I missed my pack with field jacket and sleeping bag. There was no way to keep warm. I suffered most of the night and was glad to see the sun rise. The cold weather prevented most Marines from getting any sleep during the night.

We recovered our packs and made our way toward the Han River. A great deal of activity could be heard and seen taking place on the other side. We came to a newly constructed pontoon bridge with traffic moving both ways. We finally got across, and that's when I saw the deadly price Marines were paying for real estate being liberated. In trucks coming back from the combat area were bodies of dead Marines piled up one on top of the other, just like stacked cordwood. We moved until dark and dug in for the night on the outskirts of the city of Seoul.

Activity taking place in the city was unreal. Planes were flying overhead dropping their bomb loads. The city was on fire with the sky reflecting a glow of destruction that was taking place below, with shock waves shaking the ground we occupied. This was the closest we came to actual combat since our landing.

The following morning my section under Sgt. McBride was ordered to join Dog Company. Our mission was to enter Seoul from the north. The road we marched on had Korean natives lining both sides, bowing and chanting what sounded like manzai, or banzai. They were the first large group of people I had seen since my arrival and this was their way to welcome us. As we got closer to our objective, rifle fire could be heard ahead but the people still lined the road. The tempo of fire increased as we entered the city.

Seoul City

Sergeant McBride, at the head of our section, became a casualty by stopping a bullet in his shoulder and one in the leg. It was now our turn to experience war as blood began to flow. We moved further into the city and took shelter behind a row of houses, falling on straw mats that covered the ground, not realizing the mats were shrouds for Korean dead lying underneath. The dead resembled Korean natives we had recently passed on the road leading there. They were all clad in white garbs and were actually dumped in a sewer trench with mats placed over the top of them.

Enemy fire kept raking the ground near the edge of the house I was behind. I could hear bullets zapping the earth next to me. All I had to do was reach out with my hand or foot and the enemy marksman would guarantee a wound that would result in a Purple Heart plus evacuation to a safer area.

A figure bolted out of the house we used for protection to a partially fenced-in yard to my left. A shot rang out. Through missing slats in the fence I could see a Korean native dressed in black. The Marine that fired his .45 at him missed. The old Korean seemed confused. No one else fired at him so he scooted back to where he came from, probably thanking the Lord for sparing his life.

Dog Company was inching its way forward, using grenades to gain control of buildings offering resistance. In all this hell I observed a very young Korean child playing in the road with a G. I. ration can. It’s a wonder he wasn't killed with all the lead flying and hitting near him. A Marine scooped him up and carried him to safety.

Toward evening I was told to take over Sergeant McBride's section. Dog Company was taking its share of casualties. It got dark so we settled in for the night with firefights keeping everyone awake. In the morning a wounded Marine was brought in by a group of Korean boys. I walked over to where he lay on the ground. A chaplain was on the scene praying over him, administering last rites. I asked, "What happened?" The wounded Marine was saying he got shot in the chest during the night, with a bullet wound that was close to being fatal. There were four boys involved, risking their lives to bring him in. Finally, as medics came to evacuate him, an emotional exchange took place. The wounded Marine wouldn't release his hold on one of the Korean boys. His gratitude was shown by offering to give the boy any personal possession he owned. Anything of value in his wallet now belonged to the boy if he wanted to claim it. That Marine (Joseph A. Saluzzi) returned home and wrote a book called, Red Blood, Purple Hearts: The Marines in the Korean War. His night of terror can be read in his book.

Shortly after this incident occurred, information was received claiming some Marines were seen hanging in the city. Dog Company was assigned the mission to go out and recover their bodies. If I hadn’t seen it, I wouldn’t have believed it. There was a sailor who jumped ship and felt more at home in combat with Dog Company. He volunteered to accompany the unit on their recovery mission. They took off and upon return were asked all sorts of questions as to what they had encountered on this mission.

My section from Weapons Company, equipped with rocket launchers, was to stay close to the Dog Company Command Post. It was late in the afternoon when I was given a fire mission. I was told there was a large building that North Koreans were supposedly using for shelter. My rocket launchers were set up and fired some rockets into our target area. Dog Company Marines then went in to secure the building. Toward evening a young Korean lad who spoke fluent English approached our defensive position, volunteering to help in any way if needed. He became a member of our unit throughout the night.

Wounded Marines became a major concern. How to get them out for life-saving treatment became a top priority. There were no helicopters available. It was dark. Finally some tanks arrived and a decision was made to use these vehicles to take them out. The wounded were helped aboard and I watched as they departed. I was given an area to defend for the night. There was a steady echo of gunfire taking place elsewhere, but our sector remained quiet.

Moving with Dog

In the morning, still attached to Dog Company, orders were given to move out. It was a beautiful autumn day. Past noon, we came to a streamlet and stopped to rest. Some Marines took off their shoes and decided to refresh their feet in the cool running stream. Morale skyrocketed with word that mail call would take place shortly. My section attached to Dog Company was told we would have to wait for our mail until our return to Weapons Company. I decided this would be an ideal time to walk over and talk to my old buddy Harry Griswald. He had just finished reading his mail and shared some of its contents with me. Harry and I received our transfer orders off the carrier on the same day.

Scuttlebutt began to circulate that Marines had acquired a new nickname. North Koreans called Marines "yellow legs that never sleep". This came as a result of probing operations by the enemy who found Marines awake and alert during their night movements. Our leggings were different from combat boots worn by the Army and clearly visible from a distance.

Dog Company moved out and we were back in the hills. Time passed. Finally our column approached a village. The point Marines passed word back that we were coming into a minefield and to use extreme caution in where we stepped. Once past the minefield we entered the village, coming to a schoolhouse with an adjacent clear field behind it. To its left was the start of a high ridge that we started to climb. Communications were by word of mouth relayed from one man to another down the line.

Mortar Barrage

We had gone a short distance up the ridge when I got word to move my section up to where the company Command Post (CP) was located. As I moved my unit up the hill, word came back up that some North Korean soldiers were seen in the village behind us. I reached the CP and was told to stay where I was. Suddenly enemy mortar rounds began to hit behind us at the base of the ridge. Word came back up that the enemy had observers located in the village behind us. We took some casualties and a helicopter was called in to evacuate the wounded.

The chopper arrived trying to land in the schoolyard, but the enemy mortar fire shifted, with shells exploding near the chopper, preventing it from landing. While this was taking place I decided this would be a good time to have a bite to eat. For some ungodly reason I felt hungry and needed something to calm me down. I took out a snack from my field ration, and started to chew on a piece of food. That's when the mortar fire shifted again to the base of the hill, forcing those below to move up the slope hoping to escape the explosions causing damage in that area. The enemy shells were now hitting right on top of us.

A shell exploded close to me. I actually never heard it go off. As I lay on the ground, it felt like a sledgehammer bashed my head. I saw stars and blacked out. Regaining my senses, I took inventory to see if I was okay. The food in my hand disappeared. Enemy mortars were still raining down. I could hear shells hitting the ground around me. With some there was a momentary pause when they landed, then a loud explosion followed. It was a terrifying experience. I heard cries of wounded around me. A lieutenant just above me had shrapnel pierce his helmet, inflicting a severe head wound. I now became aware of blood on my right knee. A corpsman checked it, tagged me, and told me I would be sent back to an aid station for further treatment. During this mortar barrage of September 28, 1950, my seagoing buddy Harry was fatally wounded. He went to assist a wounded Marine. As he was lifting him another shell exploded. Fragments of shrapnel ripped into his head and he died instantly. Whenever I hear the song Heart of my Heart, it brings back memories of Harry. It was his favorite tune. I can still picture the many times aboard the aircraft carrier Harry sang his song. It’s a shame his honeymoon had to end this way.

All the wounded were now assembled in an area near the road behind the ridge. While waiting for transportation to arrive I was now exposed to the agony and pain that badly wounded Marines had to undergo. It was a traumatic shock for me witnessing the physical harm the enemy shelling had inflicted on my fellow Marines. The lieutenant with a severe head wound kept crying and moaning of terrible pain in his head. I was surprised at the number of Marines who kept crying and calling for their mamas or mothers. The worst was hearing rasping sounds made by perforated chest wounds, air hissing as they laid breathing and dying. The Chaplain who paid us a call earlier was nowhere in sight. During this time of pain and suffering, his services would have given peace and comfort to those in need.

It got dark. Finally trucks arrived to take the wounded out. We traveled through the city of Seoul to a hospital aid station. Corpsmen were waiting, checking wounded, seeking weapons. I was surprised at their insistence on procuring pistols. They were like a treasured souvenir if a casualty had one. There was a show of excitement if any were found. I had in my possession a Marine issue .45 pistol that was assigned to me. I was asked to hand it over to the corpsmen that were treating the wounded. I just wasn’t about to part with my weapon without an argument. A discussion with the corpsmen convinced me that it was in my best interest to hand over my weapon, with assurance that it would be returned to me when I was released to return to my unit. I received treatment and was shown where to rest for the night. In the morning I was told I was free to rejoin my company. I retrieved my personal gear, plus pistol, and now had to find my way back to Weapons Company.

I hitched a ride on a jeep heading toward 2nd Battalion 7th Marines. Our journey took us through the city of Seoul. It was daylight, which gave me a chance to view the terrible destruction war inflicted on the city. Streets we rode on had wires and rubble scattered everywhere, some buildings were totally destroyed, and others were just mere shells.

Road to Uijongbu

Along the way I kept asking where I could locate Weapons Company. I finally hit pay dirt when I was told they were on the road I was on, heading for Uijongbu. I finally caught up to them. They were marching on both sides of a dirt road with jeeps and trucks forming a convoy moving between them. I found my lieutenant. He told me to report to my section, now under Sergeant Lister's command. I made my way to where I belonged in the column, taking in the scenery as I walked.

The tranquility of our march was shattered as shells exploded nearby, with everyone hitting the deck. As I lay

on the road I could see a railroad embankment that rose above the ground a few yards ahead and to the right of the

road we were on. It looked like foxholes were dug on the forward slope, just waiting to be occupied. Some other

Marines and I with the same idea in mind got up and made a rush for the shelter these holes offered. I was lucky

to reach one that wasn't occupied and crawled in. It was just large and deep enough to provide protection from

everything except a direct hit. The volume of incoming fire increased as the convoy was the main target. Direct

hits were taking a toll on vehicles and Marines. As the shelling continued, enemy shells were scoring hits on the

embankment that protected me. With each explosion I could feel the earth tremble beneath me, and at times I felt

dirt fall on top of me. Whoever dug these holes deserved a world of gratitude for the protection I got from this

shallow foxhole that protected me from the deadly artillery shelling.

This was a scary experience. Just a day before, I had been exposed to deadly mortar fire. Now

artillery shells were exploding around me. How I survived, only the Lord knows. The shelling stopped. We

vacated our holes and returned to muster with the rest of the platoon. Damage was assessed. Corpsmen were

tending to the wounded. There were two Marines from my platoon who sought shelter alongside the vehicles. Shrapnel

from enemy shells exploding near the convoy resulted in serious leg wounds to both of them. They had

portions of their limbs blown away.

My platoon leader survived a hair-raising ordeal, as shrapnel pierced his helmet without causing any injury. Without that tin pot he would have been a goner. The helmet became a trophy he would take home as a souvenir. It would always bring back memories of the day he survived a North Korean artillery barrage with the helmet saving his life.

Now that the shelling ceased, everyone on the road started to move forward. Shortly we came upon one of our tanks; it had run over a land mine and was disabled. One of its tracks was blown apart. I checked the damage as we passed by. No one inside the tank was injured. Daylight had turned to darkness and orders were given to dig in. Shelling by both sides kept everyone on edge throughout the night, the scariest time occurring when our rocket batteries opened fire. This was the first time I was exposed to rockets in action and I was impressed. Shells from a battery caisson unleashed a volume of fire I had never seen before. At first I wasn't sure which side was responsible for the activity until I saw the mass explosions going off in front of our perimeter.

The following day our unit was kept in reserve. It was during the night that I had another terrible experience. We were assigned to an area just to the rear of the forward units, with each foxhole on fifty- percent alert. I was paired with a Marine by the name of Marshall. We had agreed to a schedule on keeping awake. It was while I was dozing that I felt a blow to my head. On opening my eyes I found myself starring into a barrel of a pistol. My partner had fallen asleep while a staff sergeant was checking positions. If that had been the enemy I would have been history. The sergeant was trying to instill the importance of staying alert even, though we were behind the front line. The sergeant took a gamble with his move. I later talked to other Marines who were awake telling me they would have blown him away except they knew who it was prowling. They weren't as trigger happy as were Marines on our second day ashore. I questioned my partner as to why he had placed us in such a dangerous position. He said he was so tired from lack of sleep that he must have dozed off. I told him I didn't appreciate the blow to my head because of his carelessness, not knowing if he also got the same treatment. We got away with one this time; hopefully it wouldn't happen again.

At daybreak we were on the road heading into Uijongbu. As we entered the city I looked at the remains of what once had to be a beautiful city. The place was a total disaster. There was only one building with a partial wall standing. That was it. As we marched through the wreckage I observed many dugout bunkers used by Korean natives for shelter. Some had heavy timber buried beneath dirt to protect the structure from shellfire. Koreans standing near those dugouts watched as we passed by.

That evening my section was detailed to man a roadblock on a road located a short distance west of an intersection heading north. Shortly after dark we could hear a vehicle approaching from our rear. As it got closer we could hear a verbal exchange taking place that sounded Korean. It hadn’t reached the crossroads when a discussion took place among the senior NCOs deciding whether or not to challenge the vehicle if it took the turn toward our roadblock. Finally word was given that it was probably South Koreans who got lost and not to challenge them. Arriving at the crossroads, it made a turn and now was heading straight toward our roadblock. As it passed our position I could see the outline of a truck disappearing into enemy country. The occupants of the truck never saw or knew we were there. I was located roughly twenty yards to the right off the road on a perimeter that tied in with heavy machine-guns on the right flank, extending and tying in with Dog Company, which occupied the road leading north.

It wasn't long before activity could be heard taking place in front of where we were. It sounded like a truck was coming back. A discussion again took place as to whether to challenge the truck on its way back. Once again it was decided to exercise the same procedure as before to let the truck go by. As the truck passed our roadblock we noticed that it had picked up some additional features. I could see a field piece hitched to it and more soldiers seated in the rear. On reaching the intersection, it turned north and went a short distance to where Dog Company was located. Shots rang out. A North Korean officer inside had a pistol that was now a treasured souvenir. Enemy survivors became prisoners. The truck became a motor pool possession. The field gun could easily have been responsible for some of the shelling we had received two days back near the railroad. This episode was embarrassing to my unit. Twice in a short span of time we allowed North Korean soldiers to move freely past our roadblock without a challenge. This should never had occurred. During daylight, the identity of a truck and its occupants wouldn't have been a problem. At least by allowing them passage they came back with the gun and more soldiers that were taken out of any further action against us.

In the morning we moved out, but instead of going forward we changed direction and marched back through the town. This gave everyone a chance to again view the wreckage we had passed earlier. The weapons of war erased any existence of this community. We came to an area where trucks were waiting to take us back to Inchon. A rumor started to circulate that our job was finished and we were heading back to Japan.

At Inchon we found shelter in an abandoned factory while waiting to be shipped out of Korea. Everyone had a chance to relax and catch up on needed sleep. Bartering with natives became a game. The most sought item was fresh eggs. We hadn't tasted any since our arrival and were still being fed field rations. Korean natives swapped eggs for cigarettes or candy. Time passed quickly. On 13 October we were taken to the waterfront where our ship was waiting. It turned out to be an LST USS 973, manned by Japanese seamen. Rumors of going to Japan vanished.

Operation Yo Yo

As we left port on October 15, 1950, we received information that our 1st Marine Division would make a seaborne invasion on the beaches of Wonsan harbor, scheduled to take place on October 20th. Aboard ship I shared a bunk area with a World War II veteran who was one of the first Marines to occupy Japan. He met a Japanese girl, fell in love, and they ended up married. He was spending a great deal of his time lying in bed reading mail from home. This aroused the curiosity of some of the Marines sharing the same quarters. They asked him why he wasted so much of his leisure time reading the same letters over and over. That's all it took for him to unwind. He sat up on his bunk with letters still in hand and began to answer the question that was raised. It was a personal account of being married to a Japanese girl and their life together, going into detail about customs, respect, and love they both shared. We all just sat spellbound and listened while he narrated a beautiful love story. He was a sergeant with H & S 7th Marines. It would have been great if the story had a happy ending. As in every war, someone pays the ultimate price. The sergeant’s dreams of returning home ended at the Chosin Reservoir. He died from enemy fire that riddled the vehicle he was in as his unit was fighting its way out of the encircled town of Kotori.

As D-day got closer a problem developed. Mines were spotted in the waters around Wonsan, resulting in a mine sweeping operation to ensure safe passage for the troop ships involved. This delayed our landing until the 26th of October. On D-day we boarded Amtracs and started to move toward our landing zone. This would be my first amphibious landing against enemy defenses and I didn't know what to expect.

We hit the beach but there was no opposition because Korean army units had raced from the 38th parallel and

secured the area prior to our landing. Information that the landing zone was neutralized was withheld from us

until we came ashore. One Marine, a veteran of the war in the Pacific, leaned against the landing craft on shore

and remarked, “Man, It sure is nice to light a cigarette and not have to worry about being shot or killed."

Moving off the beach, I surveyed the enemy fortifications that were in place waiting to repel any invading

intruder. There were bunkers, trenches, and fire pits protected by barbed wire; also dirt covered enclosures to

protect aircraft and vehicles.

Leaving the beach behind, we marched past a Marine Air group that was in place and operational. They got there before us. Good natured ribbing was dished out by the flyboys. No one took offense. It was great to be alive and the enemy was nowhere in sight.

We came to a road that took us into a town and stopped. While resting I looked over the buildings that lined the road. It looked like they had escaped any major damage. Finally word came down that we had a long way to go. Ten minutes breaks would take place every hour until we reached our destination. Twenty-plus miles later we arrived at a monastery--our bivouac area for the next few days. Lying around aboard ship with no physical activity caught up with me. At the end of the march lugging a full field pack, I ached all over and could hardly move. I imagine others felt the same. That night I slept on the floor and when morning came I was still in agony.

North to Chosin

After breakfast my unit moved out on patrol to reconnoiter hills near the monastery. The longer I walked the better I felt, and gradually all my pain disappeared. The terrain reminded me of home during hunting season where I worked the fields to scare up pheasant or chase deer. We encountered no enemy. Our patrol ended so we returned to the monastery and relaxation. It was a Catholic monastery with nuns in control. One of the rooms was used as a science laboratory. It was a shame to see the room a total mess with specimens splattered all over the floor and some in broken jars laying just outside the building. It had to be a diabolical person or persons to inflict this kind of destruction.

There was a variety of farm animals running loose. Sergeant Lister found a choice goat, decided it was time to change our diet, and butchered the goat. We used a bacon ration as lard in frying the meat. The share I received wasn't much, but it sure tasted delicious. It was only a matter of time before nuns became aware that some of their livestock had begun to disappear and notified officers in charge as to what was happening. The following day orders were issued: Any one involved in killing livestock would be severely disciplined. I heard the remainder of our goat disappeared into a well.

To kill time, some Marines played poker. A Marine by the name of Kotek won a thousand dollars. He was the big winner in the game. There were reports of North Korean soldiers in the vicinity. Some had engaged Marine outposts in a shootout, so we were alerted to exercise caution around our area, especially at night.

The following day our regimental commander, Colonel Litzenberg, held a troop formation. He had some new important information he wanted to share with us. We were told about reports of Chinese soldiers crossing the Yalu border into North Korea. He went on to say this could very well be the beginning of World War Three and that trucks would arrive shortly to move us north to meet the new enemy. We waited until dark before the trucks finally arrived. We got aboard and headed north toward Hungnam. From there we moved north to Sudong.

On November 1st we reached our jump-off assembly area. That night laying in my sleeping bag, I felt something crawling over me. It could have been a snake or some other creature. It disappeared before I could make out what moved across my body. At dawn we saddled up and marched north to relieve South Korean soldiers who supposedly were fighting Chinese. Rifle fire echoed from hills as we got closer. Rifle companies came under enemy fire as relief was taking place. South Korean soldiers who were relieved were observed coming down from the hills. Our section continued moving north until ordered to climb a hill on the left side of the road.

We stopped at a Korean house and were told to form a perimeter around it. The house was protected by a stone wall and we used it for our defense. The wall was at least three feet high, encircled the house, and gave us protection without the need to dig foxholes. A battle raged nearby; heavy rifle fire was being exchanged. Enemy shells rained down, exploding close to the house, but none caused any physical or material damage.

That night someone said we were surrounded. With all the activity taking place nearby, hardly anyone slept during the night. In the morning a Chinese soldier was seen running on a railroad located a few hundred yards to the right of the road below us. Everyone with a rifle opened fire trying to bring him down. The man fell down and just sat there. Marines from a hill above him ran down and took him prisoner. From our distance we couldn’t tell whether he was wounded from our rifle volley or whether he stumbled on the railroad stones or ties. He may have been hit, which could have been the reason for him going down. He was the first Chinaman I saw. He must have carried a lucky charm to survive the volley of shots fired at him.

It was time to move. We saddled up, moving down to the road, heading north, crossing a small wooden bridge with a narrow stream flowing underneath, and coming to a mountain pass with cliffs on both sides. The road began to pitch upwards as we marched, approaching the stillness of death as we came upon the bodies of Chinese soldiers lying in the culverts on both sides of the road. They were probably on their way to engage us but were gunned down by our rifle companies occupying the high ground above. There just wasn’t any place for them to seek shelter. They were the first dead Chinese I saw. There were so many of them lying head to foot in a row from one another it looked like a domino effected scene where one man went down and the others followed. No one in my unit stopped to check the bodies to see if there were any wounded among them. There was always a chance some could have survived by playing possum. Further up the road the terrain leveled out with reports reaching us that Chinese tanks were spotted dug in waiting. We were the anti-tank platoon and this was our specialty. We therefore expected to be given the assignment to take them out.

We proceeded forward, passing some of our artillery guns that were dug in shelling the enemy. A short distance from the guns, enemy shells started to drop and explode near us. I dropped to the ground for cover; the enemy guns were seeking to destroy the field pieces we just passed. Nearby a Marine from my section sought shelter behind a huge rock. A shell exploded in front of the rock. The explosion had a devastating effect on the Marine. He was now seen trying to dig a hole in the ground with his bare hands, blood dripping from his fingers as he cut himself on the rocks in the earth. This was his second shell shock experience. The first took place outside of Seoul. He was hospitalized at that time, but when rumors of the Division going to Japan surfaced, he voluntarily left the hospital to rejoin his company, never expecting to be exposed to combat again. The shelling stopped. We moved ahead to where the Chinese T-34 tanks were dug in. We got there too late; they were already destroyed by our air support. A halt was called; I could now sit down to relax alongside the road.

In the field to my left I observed some Marines walking toward a stream and into it. A shell exploded in the water near them, I watched as some Marines fell. From where I rested, I could see other Marines rush to assist those in need. Word came to move out, so I couldn't tell whether those that fell were wounded or killed.

That night I found shelter in a dugout alongside the road. There was an older Marine with me--a reservist who was activated due to manpower needs. During the night he kept telling me about this feeling he had that he wasn't going to survive the war. It was a premonition that wouldn't go away. I told him to forget about dying and to be more optimistic about surviving--that he made it this far without a problem and his luck would hold. But all my effort to rally his morale was of no avail. He was adamant he was destined to die. He just didn’t know how soon it would happen. Random enemy shells continued to explode in the area near us. Luckily, we lasted the night and we both survived. It appeared enemy troops encountered since the beginning of November had taken a terrible beating and were now withdrawing. Lately resistance was light or none at all.

The next day we boarded trucks and rode up a precipitous mountain road with no shoulder on the left side. It was scary just to look down the sheer drop to the bottom of the gorge. A careless move on the driver’s part would carry everyone in the truck to certain death. Still a good distance from the top of the road, we had to cross a narrow bridge built against a sheer mountain wall, with only a footpath allowing passage on the side of the hill. The bridge was the only link connecting the road used to supply forward elements of the division. All vehicles, whether jeeps, tanks, or trucks carrying ammo supplies, field rations, you name it, had only this bridge to get across. There would be no way out for any vehicles if the bridge were blown away.

Schoolhouse Action

On November 10th, the Marine Corps birthday, we entered Kotori, There were no festivities to celebrate this special occasion. The weather turned bitter cold. We slept on the ground without digging foxholes. It seemed like the weather was getting colder each day the further north we moved. The night passed quietly. In the morning we advanced toward Hagaru. A plane crashed not far to the right of the road we were on. Some Marines went over to view the wreckage and to see if the pilot survived. Unfortunately, his luck had run out, adding another dog tag to the growing list of KIAs in Korea.

We advanced to a pass, setting up positions atop the ridge. It was dark and we bedded down for the night without digging in. We now had a new enemy to contend with--freezing cold temperature came calling during the night. In the morning as we prepared to leave the ridge, some Marines complained of numbness in their feet and were told to rub them so they wouldn't freeze. That’s when problems with frostbite surfaced. We still wore our original summer clothing that we had came ashore with at Wonsan. We weren't equipped to cope with this new enemy. As I was coming down the hill I saw one individual's hand. It had swollen to twice its normal size. This was my first exposure to a frostbite injury. As far as I knew I had suffered no ill effects from the cold that night other then freezing my butt and feet. We had no winter clothing to protect ourselves from the elements encountered during the night. Unless winter clothing was issued immediately, there was no telling how long any one of us could survive in the frigid weather.

In leaving the area, little did we know that a major disaster would occur in this location in the near future. On the road again, we set out for Hagaru, crossing a frozen stream, arriving in town around noon. There were houses everywhere--a luxury we hadn't seen for a few days. Later in the afternoon we were taken to a building where winter gear was issued. I got my shoepacs, parka, winter hat, vest, gloves, etc. The timing was a day late for some, but a blessing for the rest of us.

A plane had crash-landed in a field not far from the buildings in town. Someone with a great deal of wisdom decided this would be an excellent location to build a landing strip and work commenced immediately. As luck would have it, we said goodbye to the houses and moved out to form a perimeter on the north part of town. We got there before dark and found the place loaded with standing haystacks everywhere. Since there hadn't been any sign of enemy activity for the past few days, we decided to use haystacks as shelter for the night. I crawled inside of one with my partner and spent the night here. Amazing how warm it kept us. The only worry was, no one dug any fox holes that night. It would have been hell without them if the Chinese had come to pay us a visit.

A decision to man skeleton outposts the next day gave us a chance to move indoors. We occupied a schoolhouse a short distance to our rear. Relief took place every two hours. A heavy machine gunner named Miller came down with the flu and the runs. He was in bad shape, yet refused to be moved from his gun position to the shelter of the schoolhouse. Talk about a dedicated Marine--he had to be one.

During the night while I was in the house, a Marine ran in shouting that Chinese were seen entering the building. Someone said the garage. I was awake and fully dressed minus my parka when this took place. There was now a mad scramble-taking place as everyone reacted to what they heard. I heard someone yell to vacate the building. It took only a second or two to slip into my parka, and grab my rifle and cartridge belt. I then heard the same voice yell to use the window to vacate the building. It took less then a minute and I was outside the building. Some Marines on hearing word to clear the building didn't waste any time, vacating the schoolhouse leaving shoes, winter clothing, and even personal weapons behind. I couldn't believe they would vacate the building dressed as they were in this frigid weather. As we prepared to take action against the enemy in the garage, my former foxhole buddy, Marshall, a physical fitness nut, vacated the house without his weapon or winter clothing. On being told Chinese were in the garage, he immediately dashed inside. Shots rang out; Marshall came out holding his arm. He was hit and blood stained his clothing.

This set the stage for everyone to fire into the garage. Some fired their carbines on full automatic just to saturate the building. A Marine officer arrived on the scene and had a couple of vehicles moved into position, using the headlights to illuminate the interior of the garage. Now the shocker took place. The garage was empty. Then how did Marshall get shot? I listened as officers conversed, saying the Air Force was alerted all the way to Japan, ready to supply air power if the need arose.

Sergeant Lister came over and told me to relieve a machine-gun outpost. I got my gear together and set out to make a tag relief. The outpost was located on the extreme north part of town inside a haystack. Only a fire lane was clear. It was a cold, dark, brutal night with gusting winds adding a chill factor that made it a great deal colder. Shortly after my arrival an explosion occurred near my gun position. With the excitement that took place at the schoolhouse just before coming there, and now the explosion going off near me, I didn’t know what to expect as I scanned the area around me trying to locate any movement. I finally decided it was a "bouncing Bettie" [grenade] that was responsible for causing the noise I heard. As I sat there freezing and daydreaming, I was jarred alert as another explosion took place. More explosions occurred near me. Each time one went off I tried to see if any enemy were trying to infiltrate our perimeter. I couldn’t see anyone and wondered what had caused the explosions. It could have been a small critter, or winds blowing hard enough to cause our booby traps to detonate, if that was what actually happened. I was stationed at what should have been a two-man outpost, but there I was all alone and couldn't see where our next listening post was located. I wasn't even sure my machine-gun would fire in the cold weather. It was a long, scary night. With daylight came my relief.

I now had to know what occurred at the schoolhouse during the night. There were two explanations. One was that whoever sounded the alarm may have seen a relief group returning to the building, mistaking them for Chinese. The second story I heard was that Marshall had been riding this tall rebel for quite some time. Seeing Marshall race inside the building, the rebel opened fire and those were the first shots we heard. If Marshall were killed with the Chinese in the garage, then there wouldn't have been any suspicion directed toward him. Unfortunately, absence of any dead bodies made the situation difficult to explain. I never saw the rebel after this incident. We had to admire Marshall's valor, willing to take on the enemy with his bare hands.

Our unit was relieved when another outfit moved in and took over our perimeter. This move was a real blessing. As we moved back to a house near a stream that was completely frozen, there was more activity taking place in this new location. One day some reporters came by, took some snapshots, and asked our names and where we lived. The photo I was in appeared in my local newspaper back home. Sergeant Lister figured it was time to change our diet and cook up a special treat. All we had eaten since leaving Wonsan was a steady diet of field rations. Once word got out as to what was going to take place, everyone got involved. A large kettle was available in the hut. We pooled our assortment of field rations and in a dirt mound near the house we dug up some potatoes. All these goodies were dumped into our pot. There was a stove in the house. Someone started a fire. Our goulash was placed on the stove to cook; the hot meal in this cold weather was a treat with all credit going to Lister for his ingenuity. There was another benefit, too. The heat from the stove traveled into flues buried in the floor. It was like having our own electric blanket, with the floor radiating heat. That night I tried sleeping on the floor. It was nice and warm. At times it got uncomfortable, but it was better than being outside in the freezing cold.

Road to Yudam-ni

Our stay there was short. We had to relocate northeast unto a road leading to Yudam-ni and set up a roadblock. When we arrived at our designated area, I got my shovel out and tried to dig a foxhole. Instead, I found myself spinning my wheels. The ground was frozen solid. Each attempt to penetrate the dirt proved a failure. Finally someone came over with long-handled axes. There were only a few to go around, so once a Marine with the axe broke through the frozen ground it was then passed on to the next man in need. While we were digging, a bulldozer arrived and dug up a shallow pit just behind our foxholes, pushing dirt into a mound-facing northwest. Once our foxholes were dug, it then became a challenge to see who could erect the best protection for the top of the holes. Finally each hole had overhead cover. Some were better than others, depending on where the wood came from. It also helped in keeping some of the cold weather out.

It was Thanksgiving Day, with rumors circulating we would be home for Christmas. A new offensive scheduled for the following day was to take us to the Yalu River. If the offensive was successful, a link up of the X Corps units with Eight Army would hopefully end the war in Korea. That evening we celebrated with turkey and all the trimmings. On the way back from the mess tent I walked by our G-2 tent where a couple of old Koreans were being questioned. I watched as the officer in charge was told that many, many Chinese were in the hills, pointing in the direction of where they were seen. If that information was accurate, were they waiting to attack or was the information given to deceive us? I then left and proceeded to my home for the night. This would be our last day at Hagaru. In the morning we were scheduled to leave for Yudam-ni to join the rest of our battalion.

The night passed quietly. Early the next morning a number of field ambulances passed through our roadblock heading for Yudam-ni. We were in the process of preparing to leave when some Marines were spotted running toward us on the road leading from Yudam-ni. As they entered our perimeter, they said Chinese soldiers were waiting in ambush and had shot up their ambulances. They were lucky to survive. I looked at the high ground in front of my foxhole. Chinese soldiers could be seen moving south in the direction of the road where the survivors had just come from. The Koreans the night before were right on the money in pin-pointing where the enemy was located.

Fox Company from our battalion was located a few miles up the road. Information of Chinese cutting the road between Fox Company and us was immediately reported to our C.O. Shortly, a .75MM recoilless rifle was brought up. They positioned their weapon and got ready to shell the moving enemy. We, in turn, were alerted to move away from behind their gun because it had a tremendous back-flash that could kill or severely injure anyone close to its blast. While waiting for word to move out, we watched the gun crew shell the moving Chinese.

Our orders were to relocate to Yudam-ni. With everyone saddled up, we marched to a truck assembly area and were told to climb aboard. It didn't take long for the trucks to move out. Everyone in our section was concerned what would occur once we got near where the Chinese ambush took place. All the trucks we rode were covered with canvas tarps. Passing our departed roadblock, tension was high. We hadn't gone far when the trucks stopped and we were ordered to dismount. If the ambulances hadn't tested the road earlier that morning, it would have been our trucks that now would be exposed to hidden Chinese fire. God only knows how many casualties were prevented by the earlier encounter.

The word came down that we would make an assault to destroy Chinese positions blocking our way. Lieutenant Henderson, .81MM mortar platoon W-2-7, led the attack. As we moved out in the assault, Chinese troops were ready. Lieutenant Henderson had taken only a few steps when he fell from a bullet wound to his stomach. There were other casualties and the attack stalled. There was a great deal of confusion. New orders were issued, and Sergeant Lister was told to have his section occupy the north side of the road. As we moved off the road, a heavy machine-gun Marine was being assisted to the shelter of the hill. He had suffered a severe head wound. His bandage was stained with blood and he kept moaning with pain.

Sergeant Kraus, a section leader in our platoon, was ordered to clear a hill on the right flank of the road. From our position we watched and waited as Sergeant Kraus led his section up the ridge. There was no preparatory mortar or artillery fire to aid the unit as it advanced toward the Chinese. Near the crest of the hill, the unit ran into a buzz-saw. Sergeant Kraus was killed instantly and the rest of his section was pinned down taking casualties. Marines in the attack were having problems with their weapons firing. For example, one Marine--I believe his name was Corporal White--ran into a Chinese soldier who had a Thompson submachine gun. The Marine's carbine jammed and would not fire. The Chinese soldier's gun also failed to fire. Another Marine named Miller coming from behind, also with a carbine, had the same problem. His weapon jammed. They bayoneted the enemy soldier, claiming the Thompson as a prized possession. Later one or the other could be seen carrying the Thompson. It was evident that the unit that had been led by Sergeant Kraus was in trouble and needed help.

Sergeant Lister was ordered to take his section and help extricate the wounded and the rest of Kraus’s section off that hill. We went over and found the unit moving down, and aided the wounded that needed help. Kotek, a big winner in poker the month before, was shot in the groin area. Hopefully for his sake he was able to retain his poker winnings. Once everyone was back on the road, a decision was made to forgo any further action against the Chinese. We returned to Hagaru leaving all our dead behind. The roadblock was again our home for the night.

The following morning all Marines in Weapons Company were assembled and told we were going back to dislodge Chinese soldiers blocking our passage to Toktong Pass where Fox Company was dug in. This time there were no trucks to ride. We had to dog it on foot, so it took a while before we got into position for the new attack.

We approached the Chinese positions with a tank in support on the road. Our orders were to take the ridge that Sergeant Kraus had been killed on. Everyone was told to fix bayonets. We deployed in attack formation and started up the hill. It was a textbook assault as .81MM. mortars walked us up the slope. The Chinese were waiting for our attack, and as we got closer enemy riflemen opened fire. Bullets were flying, seeking victims. The tank on the road was dishing out its share of firepower.

As we got closer to the top, I heard Ballard Lawing to my left yell, "I'm hit. I'm hit." As he fell to the ground, I dropped alongside of him. He kept yelling, "It hurts. It hurts." I asked where he was hit and he said in the back. I checked the back of his parka and saw what looked like a bullet hole but no blood. I told him I would take a look to see how bad it was. I then proceeded to peel the layers of clothing off his back. As the last piece of underwear was removed I relaxed upon seeing the extent of his injury. I now understood why he was screaming when he got hit. I told Ballard (we called him Tennessee Toddy) that this was his lucky day. The bullet burned the flesh across his back, leaving a red streak similar to a whiplash. He felt the pain as the bullet burned his flesh. If that shot were fired a second or two sooner, Ballard would have been in deep trouble. I was the third man on the extreme left flank going up the hill with Ballard and Douglas was to the left of me. The bullet that hit Toddy had to come from the area of the road where the tank was located. Chinese to the left of the road were receiving fire from the tank and had a clear view of our move up the hill. They were trying to take us out. Now that I knew Toddy was okay, I turned my attention to where all the shooting was coming from with bullets still zipping by.

I had cleaned my rifle the night before with gasoline. I wanted to be sure all the oil was removed from my rifle to prevent any malfunction. I didn't want to find myself face to face with a Chinaman and having a jammed rifle like Marines had experienced the day before. We were now in a position where Chinese grenades were raining down on us. I watched one Chinese soldier get up and toss his grenade. I zeroed in on him, but he dropped before I had a chance to fire. I waited, thinking he would try again. Sure enough, he didn’t disappoint me. This time I was ready as he stood up, brought his arm back, and tossed his grenade. I fired a few shots, watched him fall, fired a few more shots at him, and then my weapon went dead. My God! What happened there? Now I was in the same predicament as Marines the day before. Would I survive the next few minutes? I checked my carbine, trying to find what had caused this to happen. I was astonished to find the operating rod had come off the bolt. I never heard of any such incident ever happening before. I didn't panic, but rather, worked quickly to reassemble the rod unto the bolt. With the carbine assembled, I now pressed up the hill hoping my weapon wouldn't fail me again. Above all the noise I could hear the commanding voice of Sergeant Lister, a World War II veteran, yelling to those around him to look out for foxholes. "If you see any, use grenades on them", he said. I could hear fellow Marines yelling, "I got one. I got another one." It sounded like a turkey shoot. As I got closer to the top, I saw a Chinese soldier a few feet from me. I quickly got a shot off at him. The rifle aimed at his head didn't fail me. I walked over and looked at the man I had just shot. With all the lead flying the scene could have been reversed, but it wasn't my time.

"Keep moving, keep moving" were words that took me away from the fallen enemy as we proceeded to take the crest of the ridge with hardly any loss. Once atop the hill, an eerie silence took over as the shooting stopped. There was a great deal of excitement displayed by Marines following this successful assault against the enemy. This was a new day and the hill that posed a problem the day before was now in our possession. I looked over the bodies of dead Chinese and noted clothing they wore was different from the ones we encountered earlier. These wore what looked like a faded white to blend in with the snow. The ones we had encountered earlier wore a standard brown color. They also wore sneakers in this cold weather. I don't know what the rationale was behind that. There was another surprise. The grenades they had thrown at us had caused very little damage. They were wooden concussion grenades, with wood splinters causing some of the wounds.

I went over to where Sergeant Kraus went down the day before. A bullet hole could be seen on his forehead dead center above his eyes. As he lay there, it brought back memories. I was one of three Marines sent to secure berthing for our company aboard the USS Bayfield at San Diego Harbor. We arrived a day before the rest of the unit was to arrive. There was liberty that night, but only two could go. We drew straws to see who would be left behind. It turned out I drew the losing straw. A short time later, Sergeant Kraus came over and asked if I really wanted to go. I told him I had never seen this part of California and since this was our last night there I really wanted to go and see what the town had to offer. That’s when he told me I could go in his place and he would stay behind. I'll always remember him for his generosity that day.

Back to Hagaru

With the ridge in our possession, I expected to hear orders to sweep the flank toward the road. I watched as the officers involved in this operation held a conference to decide our next course of action. Shortly word came to relinquish the ground we just took. They made a decision to return to Hagaru. A golden opportunity was at hand. Chinese surrounded Fox Company, located four miles from Hagaru. We had punched a hole in the ring and now failed to take advantage of our success. Maybe our need was greater at Hagaru or else we may have run short on ammo. I'll never understand why we didn't press further. We had taken some casualties in this assault and one Marine that wouldn't be going home was the Marine with a premonition. He paid the supreme price that day. I can still recall the night we spent together. He just knew it was going to happen and he wasn’t disappointed.

On returning from the ridge, there was a gunny sergeant waiting for us on the road. I overheard him saying to another Marine Non-Commissioned Officer that he just didn't have it anymore. That's why he didn't participate in the attack with other members of his platoon. Once inside our perimeter, we found reporters waiting to hear all about our encounter with the Chinese, trying to extract as much information as they could. Maybe our episode made the news wires back home that night or else they needed information for Marine records.

Marine engineers worked day and night building a landing strip with floodlights to assist them at night. The Chinese attacked Hagaru from the southwest and northwest of our position. It started before midnight. When the Chinese attack began, I could see muzzle flashes in the dark with bullets whizzing overhead or slamming into the bank made by the bulldozer. Shells were dropping and exploding near our foxholes, but none causing any casualties. We expected them to hit us from the east, but coming in on the road leading to Fox Company, they hit Fox instead.