|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||

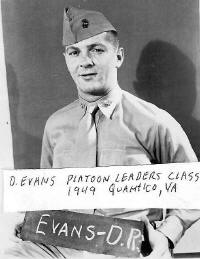

David R. EvansCincinnati, OH "For years after these adventures, I also thought what if I had done something different. I relived that Bunker Hill adventure for years in my dreams, and out of the blue I would smell gun powder (cordite in the shells). It is so hard to believe anyone could survive, and I will never understand how I could be so fortunate. As the years go by and after 48 years, some of the memories of those days make me wonder what really happened, or if some of the incidents were only a bad dream. In looking back, every Marine on that hill was a hero, and brave beyond description." - David R. Evans

|

|||||||||||||||

Memoir Contents:Pre-MilitaryMy name is David R. Evans of Cincinnati, Ohio. I was born August 19, 1929, at Zanesville, Ohio, a son of George R. and Gail M. Slenker Evans. Father was a civil engineer and a surveyor, and my mother was a telegraph operator for the railroad before she was married. After my parents were married, Mother did not work outside the home. I have two older sisters, Nancy Anders (born November 1920) and Ruth Rose (born May 1925), and a younger brother, John T. Evans, born May 1934. I went to grade schools at Zanesville, Westview and Lincoln through grade 4, and Athens Rufus Putman grades 5 and 6. I graduated from Athens High School in 1947. I worked at several jobs during high school, including loading trucks for Pepsi Cola, as a laborer for Athens Lumber Company, the City of Athens and Fenton Road Construction, and as an usher in Schines Theater. I was also a Boy Scout three or four years, reaching the Star Rank. We camped out year round and had a school gym to play basketball in sometimes. I grew up during World War II. My cousin was killed in action at St. Lo during World War II. There had been other veterans in our family as well. Father was a World War I veteran; an uncle had been wounded in action in World War I, and my Grandfather Slenker had been wounded in action in the Civil War. As a youth during World War II, I collected scrap metal, bought War Stamps and War Bonds, and was in the Civil Air Patrol during my high school years. As a senior at Athens High School in Athens, Ohio, I was a pretty good athlete. Athens was the home of Ohio University, and even though I knew all the coaches of all the three sports I participated in--football, basketball, and baseball--my only offer approaching a scholarship was a part-time job as a bus boy in one of the college dormitories. While school was going on, I could pick up a few dollars every month for spending money. In contrast, I was offered a full scholarship to play football and/or basketball at Marshall College in Huntington, West Virginia that included room, board, a part-time job, and a small amount of money that would be given every month. Needless to say, the urge to get out of town was very strong and the price was right. This was in the spring of 1947. Just prior to graduation, I had a job as a night watchman at our local Athens Lumber Company. At this time they were on strike. I had worked there in the prior summer and knew all the employees. The owner's son was one of my best friends. The owner decided that since the regular night watchman had been ran off, the strikers wouldn't harm a local boy who had worked with them and was still in high school. It worked and after a couple of weeks the strike ended and I had another summer job until I left for college. My mother left me no choice regarding college. I was going to attend one whether I wanted to or not. Being a pretty good high school athlete and a good student not only satisfied my mother's demand that I attend college, but also allowed me a chance to get out of the home nest. Since athletics had been so good to me, being a coach seemed to be a good profession. By coincidence, just about every player on the football team was a Physical Education major. Marshall College was primarily a teachers college at that time.

In August my dad dropped me off at the athletic department office and I reported for football practice. The next day I discovered that about 100 other guys had also reported for practice. Each one of us had the same promise, but only 25 would receive a scholarship. That was my discovery of the real world of college athletics in 1947. Somehow I made the cut, as probably the 25th guy. That year Marshall had a great year and as a first year "flunkie", I got to play a few minutes in the Tangerine football bowl. In the 1949 season, I played against my old home town school Ohio University, and we beat them. Revenge was mine. My roommate Dan Wickline, and my best friend Charley Barton, were ex servicemen and on the football team. As part of their scholarship agreement they worked as bar tenders at a popular local bar. One of my fringe benefits was to spend hanging out time at this establishment and enjoying cut rate prices for adult beverages on most of my free time most evenings. The USMC recruiting office was just across the street and the Marine recruiters spent a lot of their free time in this establishment, so we became friends. Joining Up

In 1949, these recruiters told me of a new program that was being offered to college men. It was called Platoon Leaders Class. This involved a college reserve recruit to spend two six week sessions during the summer at Quantico, Virginia, learning the basics of being a USMC officer. Upon graduation from college, one would be qualified to become a 2nd Lieutenant candidate. All duty was performed at the two summer sessions at Quantico, and it involved all aspects of Marine life such as fire arms use and firing, tactics, physical fitness, history of USMC, leadership, etc. Every course was taught by World War II veterans and every aspect was a hands-on affair. The students lived the training as it was taught in the field and the classroom. The Marine recruiters talked me into joining up into this program after a long evening at our favorite pub. The next morning they arrived on the college campus to take me down to the swearing in ceremony. My appearance did not pass their idea of how I should appear, so they drove me across town to my room and had me put on my suit and tie (my first taste of Marine discipline). Then we went back to the recruiting office and a captain in the USMC swore me in. A picture of it appeared in the local paper. After joining the Marine Corps Reserves, I attended two summers at Quantico, Virginia for training to be a Reserve Lieutenant upon graduation from college. In June of 1950 I was on active duty at Quantico attending my senior PLC session when the Korean War started. I had just finished my junior year in college and I thought for sure we would be immediately activated and on our way to Korea. Our PLC leader had us all together on the day of our last session and advised us all to return to college and graduate. I asked him if we could volunteer for active duty and he said the only way would be to resign from the PLC program and request duty as an enlisted man. After thinking it over all summer, I decided to resign and requested duty as an enlisted man. My request was accepted in a short time, but partly because I was back in college, I was not activated until December 5, 1950. I was busted to Corporal, and sent to Parris Island for boot camp. The Marines were always my choice of all the services from my very young years. I am sure that I was influenced by World War II movies of John Wayne and others. My roommate at college, an Army veteran of World War II, also later joined, but was thrown out for being color blind. My parents thought I was nuts to join the Marines. I joined the USMCR in April 1949, and was called to report for active duty on 5 December 1950 as a Corporal. I was to report to Parris Island, South Carolina. When the Korean War started, I was on active duty at Quantico, Virginia, and like everyone else, I said, "Where is Korea?" I sure wanted to get there. I really felt sorry that I missed World War II, and wanted to see for myself what war was like. I hitchhiked from Athens, Ohio to Huntington, West Virginia, and from there I took a train to Parris Island. Since my rank was corporal, I was in charge of the other guys that were also making that same trip. I did not know any of them, and I still don't. Boot CampBoot camp is truly the place that is the birthplace of a Marine. From the first minute, your life is like being on another planet. The discipline starts immediately, and all the other training that builds one physically and mentally is bound together by this iron discipline to succeed at accomplishing a mission in combat. All Marines don't get into combat, but all Marines are trained as if it might happen tomorrow. All training is based on working as a team (fire team, squad, platoon, company, etc.), and the repetition and practice of doing things the right way is ingrained in us. The closeness of the living, working, and performing together makes these small groups achievers and closer than family. This spirit carries over into combat and sticking together in life and death situations, and not letting your team down is the end result. This all starts at boot camp. Our train arrived at the Parris Island stop at about 0600 and some big Marine NCO ran into our coach screaming and cussing us. The main claim he made was that he hated his mother because she was a civilian and not a Marine. Guess where that put us. We were put on trucks and taken over to Parris Island. That first day we had a hair cut (skin tops), took a shower, received shots, got our issued uniforms, filled out papers, and started working on close order drill. We lived in wooden buildings on the main base, and in tents out at the rifle range. We had no insects to distract us because it was winter time. Our drill instructors were both World War II veterans. They were S/Sgt J.F. Gilroy and Sgt G.C. Harris. Our platoon was composed of reserves that were all corporals and sergeants that had enlisted in the Marine reserves after World War II and who had not been through boot camp. With the exception of two of us, myself and another guy, all the other men were World War II veterans from other services. We were probably treated no differently from other platoons of "boots", but we were older and there was a certain amount of hazing because we had more rank than most of the DIs who were in charge of training us. We had no black recruits in our platoon, but I do know that we had a few in boot camp as "boots." Boot camp was eight weeks long. We marched or double timed everywhere, and physical exercise could happen anywhere or any time. Book classes were held and slides were show in wooden buildings. This was on subjects such as map reading, Marine history, our General Orders (to be memorized), and the Marine mission. All the films we saw were strictly for training purposes on military subjects. We also had classes on various weapons, especially the M1 rifle. The non-classroom work was mainly physical exercise and learning how to maintain and use the rifle. I think we got up at 0530. The lights were turned on and in one minute if we were not out of bed, we were dumped on the floor. We had about 30 minutes to make our bed, shave, shower, get dressed, clean up the area, and fall out for breakfast. We either ran or marched to eat, and then ran or marched back after eating. About 15 minutes was given for final clean up and we were off for PE and the day's classes. There was a noon break of about an hour and then back to the schedule until about 1630. If it was a good day, we were free until about 1730 and then we marched to supper. After supper we marched or ran back to the barracks and could read, write a letter, study, talk, or possibly have a smoke (if the smoking lamp was lit), or clean our rifle completely. If our barracks had failed inspection that day, we might have to scrub floors instead of any other activity, and possibly we might have to scrub them with our tooth brush. All participated. If a Marine failed rifle inspection or dropped his rifle, he had to sleep with that rifle. At 2145 we could get in bed, but not before, and at 2200, lights went out and Taps played. I do not remember our DIs getting us up during the night. Our DI used physical exercise with or without a rifle as opposed to hands-on corporal punishment. When they spoke we answered and when they ordered we performed as they requested to the best of our ability. If a guy smoked without permission, a bucket (we all had our own fire buckets) was put over his head and we all marched past him and hit the bucket that was on his head with our rifles. I personally was fortunate in that I did not get into trouble with the DIs. When our platoon marched poorly due to one guy or all of us, we all suffered. Exercise with rifles over our heads or long double time marches were a common punishment. Discipline of a collective type showed us that if we didn't all work together, we all suffered as a group. As a result, there were no troublemakers in our platoon. Most of the ones that fell out couldn't stand the discipline and or the physical requirements. We ate well at boot camp. Meat and potatoes, eggs, bacon, chicken, liver, fresh vegetables and fruit, chipped beef, gravy, milk, coffee, juice, and cold cuts were common on our menu. At the rifle range we had to qualify or not graduate. If one didn't graduate, he had to repeat the training all over again. I qualified as a "sharp shooter." Our platoon was an honor platoon due to high performances, especially at drill.