|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||

Archie EdwardsArcola, IL- "I survived in part because I was from a poor family. And I think my body adjusted to that stuff they gave us because I had scrounged and got my food a lot when I was right here in the United States. I think that's what brought me home, being able to adjust to what they gave me. A lot of them couldn't. And that's the ones you saw that died first, the ones that had been living an easy life. I grew up on beans, potatoes, cornbread, biscuits. Maybe a little meat once in a while." - Archie Edwards

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Copyrighted by The Museum Association of Douglas County Korean War Project Interview conducted by Lynnita Brown on the 6th Day of November, 1996 at the Douglas County Museum in Tuscola Illinois. Edited by Chuck Knox January, 2003 My name is Archie Edwards and I live at 250 South Locust; Arcola, Illinois. I enlisted in the Army on November the 21st, 1945. I did it to get away, to get to go someplace, to see the world, which I did. I was 18 years old. I guess I thought it would be a great adventure. I got in right at the end of World War II. I thought this was going to be peace time activity that you were involved in but I could still see the world. A friend of mine, Orville Lynn, who had reenlisted talked me into it coming on the train going to Chicago to take our physical. I went to Fort Sheridan first. We processed out of Fort Sheridan, went to Fort Bragg, North Carolina where I took my basic training. I was there eight weeks and then sent to Germany. I was supposed to be a cook when I first went over, but they had all the German people doing the cooking for us. So I was on one day and off four days. I was in the Army of occupation. That was supposed to been my job at the time, but I never did have to do anything; just show up and be in charge of the German people that were doing the cooking for the headquarters battery of the 9th Infantry Division in Munich, Germany. I supervised probably eight or ten German workers. I went to Cook and Baker School in the States: down at For Bragg, North Carolina. I didn’t choose to be a cook, the Army just told me that was what I was going to be. I was in Germany 43 months. I'd been all over southern Germany, Bavaria. I went to, from Munich, Vilseck and Grafenwoehr. That's a training camp out in there. And then I went Fulda, Germany. From there I went to Hoffe, to Weiden and to Sonthoven. That's where I was when I came home. But I extended my time over there. When my three years were up, I extended for another year. And I tried to extend again, but they wouldn't let me. They said I would start acting like a European if I enlisted again. I liked the country and the duty we had at the time, but it started getting a little hairy over there in '49. They started getting stricter. We were in the field about three fourths of the time out in Grafenwoehr. I came back to the States and was stationed out in Fort Lewis, Washington with the 2nd Infantry Division. I was there from September of '49 until August of '50; and that's when the whole division shipped out, went to Korea. And that's when the Korean War broke out, and my whole division shipped over to Korea. We landed at Pusan, went up to Taegu on the night of the 19th of August, 1950 On the next night, the 20th of August, 1950 a big rain storm came and washed all of our stuff away. They’ve got monsoon seasons over there. I was at Taegu. We got there by trucks from Pusan. I was a gunner in the 105-millimeter Howitzer outfit. And we pulled the gun around with a deuce and a half (2 1/2 ton) truck. We had all of our equipment on the truck, plus pulling our gun around with us. Taegu was just a group of mud shacks. When I landed in Korea, I wanted to turn around and go back home. There were a couple of hospital ships lined up there with the wounded. They were trying to get them off. They were bringing the wounded in though. That's when they about had everybody shoved off of the peninsula. There were probably dozens and hundreds. I don't remember exactly how many there were. But at that time that's when they were getting clobbered pretty good. I didn’t think much of the country. It stank like manure. About the only thing you saw over there are what they called these honey wagons. That's what they haul human waste around in to put in the rice paddies and stuff like that. It stinks. Stinks everywhere you went. It's just like before the Koreans would hit you, you could smell garlic. They all eat garlic, red peppers. You could smell them. When we got to Taegu, we built parapets around our guns. You lay your guns - in 105 Howitzer you never see what you're shooting at. It's indirect fire. We laid all the guns in. Only time you fire direct fire is when a tanker is so close on you that you can't shoot indirect fire. You've got to shoot direct fire then. We had the parapets so if an enemy round hits in that, it won't kill everybody in the section there. We had a forward observer up there who's directing that fire. We call him an FO, forward observer. He's up closer to the lines with the infantry. He's got a radio man with him; he's got nobody protecting him. The infantry's out in front of him. He picks the highest point that he can see so he could see good and then he'll call in the direction of fire to your people back in the rear on the guns, and they relay that message down to your gunners and then they all fire. Well, one night it flooded. We were kind of camped along a little ditch. Seems like a flood came down through there. We had all of our duffle bags and stuff laying in this little ditch. And it came down so quick and hard that it just washed our stuff away. It seemed like we were either chasing them, the Koreans or they were chasing us. You never had much time to do anything over there. They got close enough to us that I killed three that I know of. The ones that I killed were Chinese; and they had gold teeth, so they must have been officers in the Chinese Army because your regular peasant didn't have gold teeth. That's how you could tell. When they captured you, they would feel your hands to see if you had calluses on them. If you wore glasses, you're liable to get struck; because they thought that people who wore glasses were rich. And, if you didn't have any calluses on your hand, you didn't do any work. So you're liable to get hit if you didn't have calluses on your hand. I was on line a hundred and one days. We went on through Seoul, Pyongyang, which is the capital of North Korea on up to Sinewiju. That's up on the Yalu River. MacArthur wanted us to get up to the Yalu River. Then he told us we'd all be going home for Christmas. But in the meantime the Chinese were encircling us. We never did see them. Nobody believed that they were there. They did their moves mostly at night. Seoul was pretty good sized town, but it was flattened by the artillery, mortar shells. My outfit helped shell the place. I think the Marines went through first. Then the Second Division followed up. That's when the Marines landed on Inchon. See, we were stuck in South Korea there. We couldn't get out of South Korea because we had too many North Koreans in front of us who couldn't do anything. But, when the Marines hit Inchon that cut the North Koreans off. They cut their supply line. They couldn't get back. That's when everybody broke out of the Pusan Perimeter and started heading north. I think it was September the 25th, I believe, of 1950. We were on the move all the time prior to the Inchon landings. We were getting shelled, and we were shelling people all the time. I was on the Red Ball Express. That's hauling supplies up to the front for the troops. I volunteered for it because I knew there was going to be some good eating there. I took some good eating back to my men when I got done there. Cigarettes, strawberries packed in syrup and stuff like that, which we'd never seen on the line. I think that was for the officers. Your enlisted man didn't get anything like that. The enlisted man got a good meal but it wasn't anything like that. We just didn't see some of the finer things that went around. I was escorting the truck. I had a driver, my regular driver with me. The trucks were regular Army deuce-and-a-half trucks. We were delivering up around Pyongyang. My rank at the time was Sergeant, Staff Sergeant, four stripes at the time. I was a gunner. I had another guy that had five of these who would tell me what to do. But I got this other stripe when I got out of the prisoner of war camp. They give us all another stripe. We never had any rationed beer. Only time we had anything to drink is when we blew up a distillery there in North Korea somewhere. And the bottles were scattered everywhere. And the men got in there and got a bunch of that, and they hung a good one on. They had us we were outnumbered all the time we were over there. And our equipment was Second World War equipment that had been worn out. That's what we inherited when we went to Korea. We never had anything to fight with. That 2.38 bazooka wouldn't even phase one of those T-34 tanks. It would just bounce off of it. Some of the shells wouldn't even explode because of old age. And this 2.38 wasn't big enough. It wasn't big enough to penetrate the shell of the tank. Now the three point five bazookas did. We got that later on. They were using T-34 tanks that the Russians had over there. Russia was supporting North Korea. And they had all this artillery and these tanks. They had some good equipment when they started out there June the 25th, 1950. That's why they rolled right through South Korea and took everything. But the weapons we had fired all right. Most of the time we had plenty of ammunition. One time we were rationed five rounds of ammunition a day, right before we crossed the Naktong River. And there wasn't anybody that could stop the trucks from bringing supplies up. Why they rationed it, I don't know. We were on duty all the time. You never had any time off. You were doing something all the time, on the move, going backwards or forwards all the time. Once in a while you got to sleep some, yeah. Right before I was taken prisoner I hadn't slept for four days. We got packages from home occasionally. When I got a chance I would ask for fudge from old Mike Poles that used to make that fudge candy down there at Arcola at the candy kitchen. At that time it was a nickel a pound. Now you pay $5 a pound. I had two or three packages on the way for Christmas, but I was taken prisoner and I never did get them.

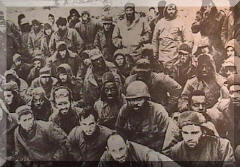

When we got to the Yalu River you could see right across and see Manchuria. We didn’t see the Chinese until I was taken prisoner I don’t think that headquarters understood the threat of the Chinese. Back in Tokyo, that's where MacArthur gave all his orders from. He was telling us all the time there were no Chinese in the war. But we were taking Chinese prisoners; and they knew there were Chinese over there. But they didn't know how many until in November the 28th. I think that's when the Chinese really came into it. I remember us stopping, setting our guns up, firing a few rounds, buckling it up, taking off and running to another spot, firing a few rounds. I didn't know what was coming off. I thought, "Well, we're winning the war. We might be home for Christmas." And all the time the Chinese were going around us, circling around us, had us cut off all the time. We didn't know it. The 25th Division was right alongside of us. Marines were on the other side of the coast. The Seventh Division was over there with them. First Cav was with us. I think they were about the first ones to get hit by the Chinese. We got hit at Kunuri. That's where I was taken prisoner. They captured us at night. They were mostly night fighters. They'd rather fight at night than they would daytime. And they were good at it. They sent out patrols to find out where we were. We sent out patrols to try to take them prisoners at night. Each Army would do the same thing. They'll send out patrols and try to take prisoners, feel you out, see how many you've got and stuff like that. We thought we were safe. The artillery's supposed to be safe. I don’t know if it is true but they told us that 600,000 Chinese hit us there on the 28th and 29th of November. They came right through our infantry. They got to us. Hell, we were fighting just like the infantry was. But we weren't infantry. The Chinese were supposed to have had 12 or 14 miles of roadblocks that they had set up with mortars, machine guns and artillery pieces. We got through six miles of that. In the meantime, they had killed a bunch of our men and were lobbing artillery and mortars in on us all the time. In fact, the Chinese were right in there with us, right alongside the road around our guns. We couldn't see, couldn't do anything. I was at a Howitzer and a Major Kapinski, my Battalion Commander, was loading my gun for me. I'll never forget that. I was firing where I thought there might be somebody. Nobody knew where anything was. I was just firing in the direction that - see over there they had a bugle that they would blow right before they would attack you. It was a bloodcurdling bugle sound. I never heard anything like it. And they'd play that bugle right before they would hit you. It was probably a charge of some kind. When they played that, get ready for because you knew that they were going to come. You ask any GI that was over there in combat if he remembers a bugle that the Chinese played. It'd make your old shirttail go up and down your back like a window shade. We lost many men. There was another battery right beside of us, a shell landed in their parapet and killed, six or seven of them. At Kunuri we were captured wounded, captured and killed. A lot of times the Chinese would kill the wounded if they couldn't walk on their own. I had five little places where shrapnel had hit me. But it hadn't hurt me that bad. I could feel it rubbing. But it finally fell out. Shrapnel will work out of your skin. They came in in droves. There was so many of them you couldn't count them. There was this one buddy of mine from Devil's Lake, North Dakota, Steven K. Roe; a shell took part of his shoulder off. And he walked 55 days back to that POW camp and laid down and died. By the time we got there we were starving. We had nothing to eat hardly. You never heard of any medical attention. To this day I don't ever remember getting any salt over there. I remember them bringing in some seaweed and was telling us that it had quinine in it, that that would help us, you know, instead of the salt. That's the toughest thing to not have salt. We walked in all kind of weather. Cold, it gets colder in North Korea than any other place in the world I believe. We walked through snow and blizzards. They had blizzards that came right out of Siberia over there. We were in the north eastern tip of Korea. We had not been issued any winter clothing whatsoever. We had fatigues, lightweight work clothes. Some of them had snow packs kind of like a boot with an insert in it. And we had what they called the Army field jacket. We walked 55 miles. We were walking all the time at night. We were in Korean houses in the day time. They must have run the Korean people out of their own houses and put us in there for that day, and then we would move out that night. We had corn to eat and they finally gave us some millet, kind of like birdseed with no seasoning of any kind. We didn't have plates or mess kits or anything to eat our food out of. All the guys took their hat, made a little hole in it like that, slop that in there and eat out of that. The millet was a little watery, yeah. It depends on how much water they put in it. You could make it mushy like or watery. No one tried to escape. Nobody felt like doing anything. We were way up north there. I never heard of anybody escaping. Some of them tried to in the POW camp. But just 300 miles from your own lines, and to get back you had to go through the North Korean Army, the Chinese Army and all the civilians. You know, Caucasian don't look like those people over there. And you could not, I would say it would be impossible to get back. We were up Pyoktong, North Korea on the Yalu River from 24th of January, the next day was my birthday. Because they thought we had influence on the privates they moved all the Sergeants up to a town on further north still on the Yalu River, the town of Wiwon. They said they were making us go to a school every morning to teach us about communism and stuff, trying to brainwash us. Every day we had to go to school, listen to them tell us how lousy our country was, how hungry the people were in the United States. You can't believe the stuff they tried to tell us. Oh, they talked about everybody. They talked about your war mongers, your big business men, like DuPont and Rockefellers with plenty of money. That's who they would run down all the time. When you look out and see nothing and remember what you had back here in the United States, you couldn't agree with people like that because they had nothing. They'd try to tell us how good they were treating us when eight and ten people were dying every night in this camp. Now that's not treating people well when you're dying of starvation every night. Sommer: And here's another thing that I get perturbed about. They’re (United States) giving these Russian officers over there in the Ukraine $40 million to build themselves new homes. And they're talking about giving four billion dollars to North Korea to build another reactor over there. You know that Russia was behind the war in Korea and Vietnam. They're rewarding them for killing 112,000 American lives, young GIs? They're rewarding them for that. I can't understand my country. But what gripes me, we were sitting up there rotting in that camp; and this place is only probably about the size of the State of Florida. And you know and I know that my country could have gone over there and taken that in probably two days if they had wanted to. But I don't know. Maybe big business hadn't made enough money. It's a terrible thing to say. They're telling us now that that was the first step to stop communism, which I don't deny it. Maybe it did. I don't know. Counting Korea and Vietnam about 112,000 American young men died for it. Sometimes I get a little bitter. Then you get to thinking, "Maybe they did have a reason". We were captured December the first, and it took 55 days to get up to Phoktong. It was supposed to been a town. Just a whole bunch of mud shacks, houses that the Korean people lived in. Must have moved them all out, because they moved us all in. It was right beside the Yalu River. We used to swim in the Yalu River every day to take our bath. We had, we hadn't had a bath or shaved or anything from the first of December until April of that next year that we had to get a haircut or shave or anything. Well, when it warmed up you could in the Yalu River. No, you didn't take a bath until it was warm. And you see when they gave you hot water; that was to drink. That wasn't to wash in. They boiled all their water over there. I didn't get to take a bath either until the next year when we could go to the Yalu River and take a bath down there. We never had soap or towels until the peace talks started and they brought a towel and a little bar of soap to us. In one hut, that was about a 12 by 12, there were 15 people. Now that doesn’t give you much room. We slept on the floor and did not have any blankets. A lot of people died but not because they froze. They were dying from frost bites, wounds, starvation and lice. And lice got a quarter of an inch big over there. You could watch them and pick them out from under your arms, around your seams of your clothing. And you could pop them. They were full of blood. Everybody looked like Wild Bill Cody over there. Mustache, long hair. I had hair down my back, and a beard. My mustache, try to eat that stuff they gave you and you'd get ahold of your mustache and you'd be chawing on that. It wasn't nice. Sometimes we would pick the lice off each other and pop them. The grain that they were feeding us was wormy. These worms looked to me something like a big night crawler. I'd say, maybe quarter of an inch, no, I'd say a half an inch wide. The Chinese gave us a pill to get rid of worms in our body. And that pretty well got rid of them for the time being. Then we started eating the wormy grain. I was all the time out looking and scrounging for something to eat. And usually I would find something like the greens; they would plant a garden the year before and not get it all in, like a garlic patch. If you got a piece of garlic to eat with a bowl of sorghum seed. It looked red. I don't know what it was. But if you had a piece of garlic to eat with that, give it a little flavor, you could eat it. That's what happened to a lot of guys over there. Their stomachs wouldn't adjust to that stuff that they gave us to eat, like your corn and your sorghum cane seed. Now rice was a delicacy over there. We had rice some times, but not very often. But, if you had something like an onion or a piece of garlic like that to eat with it, well, you could get it down. They'd give us a little mini loaf. Real little. It wasn't nearly as big as a loaf of bread. I got around the camp myself quite a bit. I was finding things like a little mulberry tree I found up on the side of the hill. I'd pick mulberries and take them back down to my room and get my piece of bread and mash them up and mix them with that bread. They went down pretty good. I didn't tell anybody about my mulberry bush. You could walk down to Yalu River. If you had a fish hook, you could fish. But you had guards around you all the time. We had Chinese guards at the time and they didn’t bother us. The Korean guards were mean. In fact, I think that's what we had the first six months during the war. Then the Chinese took over in July. That's when the peace talks started. The least little thing you'd get kicked, stomped. Beat and hit with rifle butts. I got hit with a rifle butt right along the neck. We weren’t strong enough to do any exercise. At one time I thought I was the best shape of anybody in the camp. And I dropped down on the ground. I was going to do some pushups, and I couldn't even get up. You were weak. That first six months you were so weak you didn't do anything. I knew the life's history of my fellow prisoners. I was telling you about, Steven K. Roe from Devil's Lake, North Dakota and Gene VanSteenvord also from North Dakota. There was Eddie Yeager from Devil's Lake, North Dakota. He was my truck driver. They all died. They called it a give-up-itis, but this Doctor Shytis come along and give this speech. Maybe their bodies couldn't digest the stuff that we were eating. But I was there when they all died. Eddie Yeager had a sister. I remember her, her name was Angie. And Roe and VanSteenvord, I don't remember them saying much. They thought they would get out. I mentioned a Jerry Parker that was in my section. He was from Iowa. And he had his high school class ring, you know. He was dying. I held him in my arms when he was dying. He gave me that class ring. He said, "Trade this and do what you can with it. Get you something to eat, because I ain't going to need it." Jerry Parker, yeah. He had a mom and dad. He was probably 18, 19 years old and Roe had a cigarette lighter, and this Chinese guy saw it. Roe lit a cigarette and put the lighter back in his pocket. That Chinese came over there and ran his hand down Roe's pocket, got that cigarette lighter out and lit it, smiled, you know, like that. And old Roe said, "Next time he comes over and does that I'm going to drop him." Pretty soon here came that Chinese back over there, ran his hand down old Roe's pocket, got his cigarette lighter; and Roe hit him. And, you know, they didn't do one thing to him? I never did get to know the Chinese. We had one guy in there they called Scar Face. He had a big scar on him. Somebody told us that he had got that fighting with the Americans in the Second World War. And the Americans had saved his life. He wasn't mean to anybody. Of course, none of the Chinese guards were ever mean unless you got out of line, broke the rules. If you were under the Koreans, it was the meanest outfit in the world. Starving you to death, kicking you, not giving you anything, nothing to smoke. About everybody smoked there. I was over there a year. We didn't have a cigarette. But I'd say starving a person to death is about the worst thing you could do to them. They liked hurting you. The Asiatic people are the most ruthless people in the world, most barbaric people in the world as far as I'm concerned. There in '52 they brought us a basketball. Guys kind of made a basketball court and played basketball. I never did play any basketball. But just keeping clean. Trying to find something to eat about the only way that I could find to make the place better for me, because I knew I wasn't going to get it from them. When you're starving, you don't laugh. When you get around a bunch of GIs, there's always women brought up as a subject; but in a POW camp you never heard one woman's name mentioned. Because they were starving to death. You don't have anything to eat, you don't want a woman. If you're hungry and starving you’ve got no desire. Food. Everything, everybody talking about what they were going to eat and make and get when they got out of that POW camp. Banana cream pie and peanut butter. That about drove me out of my mind. I ain't lying to you. These guys were all talking about food - I never heard so many menus as they would dream up, about the chocolate covered ants and pizzas. I never heard of anything like that. And I don't think they had either; but they said, "Well, they are good." Everybody had their own little recipe or food they were going to make when they got home. When our men died we buried them as best we could. It was on a kind of little cove back in off the Yalu River and kind of a hill up along the side of it. We took them over there and just get enough to bury them, dug it deep enough to bury them, cover them up with whatever you could, rocks, dirt. You didn't have anything to do with over there. Everything goes through your mind there in a situation like that. Like being a prisoner of war and having to bury your own friends. Sometimes I wondered if we'd ever get out or not. You know, after you're at one place 33 months and things are not going well they had a lot of propaganda they would tell us. How bad the war was going for the Americans and all the rest of the United Nations troops, about how many they would kill and stuff like that. They never did tell us how many that they lost. They'd try to make you feel bad. I remember one time they had a song by some woman that they played for us, American. I can't remember who that was. She was real popular here in the States. I don't know how they got the song. During the time that we were over there, I did receive a care package from the Red Cross on the last week that we knew we were going home. That's the only time we ever got anything from our side. There were cigarettes, toilet articles, and stuff like that. Everybody had cigarettes then. Looked like a couple locomotives going around there when they all got lit up. About a week before we got the packages, they told us that we were going home. They started feeding us good. We started getting some eggs. The cooks made a griddle; and they started making hot cakes and stuff for us with prune juice in it. We were eating pretty well there the last week or so before we got out. They were trying to make us look better before we got down to the line there so they wouldn't think that they'd been treating us bad. We had some pretty good chow right before we got out. I was captured December first, 1950 and a prisoner until September first, 1953. After the peace talks started in '51, they started letting us write a letter home so my folks knew I was alive. And that, was that my mother’s first inkling that I was alive. My mom had already written letters to Washington and everyplace about me. She got the missing in action telegram from the Army or the War Department. They let us know that they were signing the armistice. Like I said, after the peace talks started, we started getting potatoes, that were half rotten. The dying stopped after we started getting vegetables and stuff like that. Every once in a while they brought in a goat for us to butcher or something like that. Might get an inch piece of meat. We had an old boy that worked up at the kitchen, the colored boy that did the butchering, old Johnny C. Hill. He was from North Carolina. He did all the butchering for us. He was a great big old colored boy. He'd knock them in the head with an axe and butcher them. To us it was good eating, but I wouldn't think about eating it here in the States. We were separated by ranks. When we first got to Pyoktong, we were with the officers. Everybody was together. And then they moved the officers to a camp they called annex two, camp two. We were noncommissioned officers. We went to Wiwon. But the wounded didn't go any direction. They just stayed there at Pyoktong, and mostly all of them died there. We had rooms that we stayed in. You had First Company, Second Company and Third Company. Usually Third Company was all colored people. There were probably five hundred or better in First Company that I was in. There were 3,500 in Pyoktong when I walked in on the 24th day of January, 1951. And in three months 1600 of them had died. That was at Pyoktong. And that was under the North Koreans. One time I remember somebody found a little limb off of an evergreen tree and brought it in, and that was a Christmas tree. We decorated it. We finally were able to correspond with the folks at home. But, it took three or four months for a letter to get to the States and then that much long for it to get back to you. We had to build our own roads and railways to get out of that place, because gully washers came through; and they'd wash the roads away. It took about as long to get back as it did to get up there. They finally got us down far enough to get us on a truck or on a railroad. We walked part way. We pushed trucks part way. We did everything to get out of there. We finally got on a train and they closed all the windows, wouldn't let us look out the window or do anything. We were about a mile away, I imagine, from Freedom Village. That's where we were released at Freedom Village. And they kept us in a little camp there until; it must have been a couple of days before we got released. Everybody wanted to get out, right now. They wouldn't release us for a couple days. You could believe it then. When they came around and told you that you were going home, you could finally believe it. We knew something was happening because we were getting better food. I have a handkerchief signed there at the camp. Right before we left I ran around and got guys' names on it. Most of them are faded out now. The sick and wounded left before we did in an operation called Little Switch. We went out in Operation Big Switch. Freedom Bridge I think they called it. Imjim River, we crossed over that. The first thing I saw was American flag Everybody was crying. And I remember this old Colonel. I jumped off the truck, He said, "That's the way to come off of there, soldier." And then they took us in a tent there and a chaplain was saying a prayer. And everybody broke down in there and cried like babies, including me. I don't know why. I suppose that the treatment we had before and the good treatment that you was getting now just made you sad to think that you had to go through the stuff that you had to go through. To have survived something like that. We got showers, and we got milk, coffee and ice cream, real nice. We started home in a couple of weeks. We took helicopters on into Inchon, billeted in there for, I think it was two weeks. I think we got home in the States about the end of September. We came back on a ship with ex-prisoners and returning troops. There were no parades. Just celebrations from our folks. I sent a telegram that my mother got that I was released from behind the bamboo curtain or something like that. They knew I was coming. We landed in California. They processed us there. It was a day or two and then put us on a plane, a C-54, to come to Chicago. While we were on the ship we were interrogated by Americans. They were mostly wanting to know about some of the guys collaborating with the enemy over there and causing a lot of people to get in trouble. Well, you would call them spies but they would collaborate with enemy so they could get better food and stuff like that. And they had a lot of them made broadcasts on the air about germ warfare. The Chinese said that we had dropped germ warfare over there. And some of the pilots that got shot down made them broadcast home and tell the whole world that the Americans had been using germ warfare over there which they hadn't. We wanted to kill the collaborators for one thing. I didn't know any of them. But there's been nothing we could tell the Chinese that they didn't already know. They knew more about your outfit and your government than you knew. So it was nothing you could tell them that could harm anybody. I'd give them a list. In fact, I met this woman up at Schaumburg this year at the POW reunion. She was asking me about these guys. She had my name on there where I'd let them know that Roe had died Jerry Parker, and VanSteenvord. Oh, I know a lot of them; but I can't remember them. I remember one guy, a Paul Pressler from Campbell, Missouri. We all thought he was dead, and was taking him over to bury him. We didn't know, probably a lot of guys got buried over there alive. We thought he was dead. The Chinese come running down there and give him a shot of glucose (sic) I guess that's what you call it. And you know that guy come around! He got healthier as the time got by. As far as I know he's living today. When I got back to the United States, the very first thing I wanted was Banana cream pie and peanut butter. My mother filled me up. My homecoming was really good. Had a whole bunch of people, half the town turn out for me, the high school band, American Legion, VFW. I rode home by taxi cab from Chicago. Me and another old boy came together, and we paid this here old colored guy 50 dollars apiece. Now my folks lived at Dwight at the time. It was only about 60 miles out of Chicago. And we come up there in a taxi cab. Nobody met us at the airport in Chicago. We just had the taxi bring us home. Well, we spent a day in Chicago getting our uniforms tailored. Getting a suntan put on our face, buying new clothes and stuff like that. They gave us $300; but we had three years' pay coming. They sent us that later on. Oh, somebody said I was supposed to get a new car. I never did mess around and try to find out or not. This one cafe took my whole family in that night, and we had food there. That's about the only thing I can remember that I got. For being a POW the government got me my back pay plus two and a half a day for rations that we hadn't got. I think it was 1700 some dollars that I got. About a year ago they passed a bill in Washington that we all had a bunch of furlough time coming. And they give us $300 for that. I think it changes everybody that's ever seen any combat. You're not ever the same again. You don't think it would change you to see all your buddies’ dead? It will change you. You get a certain kind of sadness. I feel sad a lot of times. About my friends, my buddies. Friends and buddies that didn't come back. I don't believe it was necessary but maybe we did stop Communism. I don't know. But they’re telling the world now that it did stop communism, the Korean War did. But, if it did, why, I guess they had a reason. Vietnam, I don't know why they had the Vietnam War. It seems like we've put our nose in everybody's business but our own. We don't care for our own; take care of our own self first. I believe in taking care of this country before I believe in going over in somebody else's, jumping in and trying to take care of them. That's big business, Saudi Arabia. That's your oil companies. That's an awful thing to say. But I'm like this old Sergeant of mine. Let's call a spade a spade. I don't think it affected me one way or another, no. I think we stick our nose into other people's business when we should keep it out a lot of times. About the Americans that stayed there. I think they ought to make them stay over there. They chose that way of life. They had lived under that for about three years. They should have let them continue to live over there. As for the Chinese and Koreans; I don't want to be around them. I don't think any war should be forgotten. This went under a police action and a conflict for years and years. Now they finally decided that it was a war because 54,000 policemen got killed. Now, when that many people get killed, I call it a war. I don't call it a police action. Many people don’t understand our experiences. The things that you went through. They can't believe that they didn't feed us and treat us the way they did over there. People can't believe that. That's why I don't try to tell anybody everything, because they don't believe that you went through what you went through there. Now they’ve seen a lot of pictures on TV during the Second World War, Japanese. Maybe some of them believe it. Maybe, they don’t believe it because they have never lost their freedom and I hope they never do. I can visualize what this country would be like if a bomb drops here in this city right here how berserk these people would go. Do you know that you'll never know what to do until it happens to you? You never know what you'll do. Thank God, I hope it never happens to any of us. I survived in part because I was from a poor family. And I think my body adjusted to that stuff they gave us because I had scrounged and got my food a lot when I was right here in the United States. I think that's what brought me home, being able to adjust to what they gave me. A lot of them couldn't. And that's the ones you saw that died first, the ones that had been living an easy life. I grew up on beans, potatoes, cornbread, biscuits. Maybe a little meat once in a while. I've got good and bad things to say about MacArthur. The good part about MacArthur is he wanted to go in there and bomb China. Because they're the ones that were supplying everything to Korea in the Korean War. But the bad thing I don't like about MacArthur, he kept shoving us north; go farther north, north, north, north until we got up there and got fenced in, couldn't get out. But he kept telling us that when you get to the Yalu River, why, we'll be going home for Christmas. Everybody wanted to get home for Christmas, so they did everything they could to get up there. And they were digging their own grave all the time. Without winter clothes, we weren't equipped for it, not the Korean winters; which are really bad. I can remember this one POW one time was praying for a pack of cigarettes. He didn't know anybody was around, and a Chinese slipped up and slid a pack of cigarettes across the floor. He said, "Now can your God do that?" But those people over there, the American GI never did lose their religion. The day before we were captured we thought we were talking to South Koreans, which were our allies. They all look alike. And all of a sudden the Chinese, I guess he was Chinese, reached down and tried to take this gun away from this GI. And GI backed up and started firing. And man, I thought the world had come to an end. Everybody was firing, couldn't see anybody. And we were running. And all of a sudden Eliot was hit I kept going, and I fell over a cliff. I didn't know it was there. I couldn't see. I thought I'd killed myself, but I never did get a chance to go back and try to find him. We were running because everything was one big mass confusion. Nobody knew how they did that - probably all that firing up in the air wasn't trying to hit anybody. It was all messed up. You had your North Koreans, your Chinese, and your South Koreans. Now how are you going to tell the difference? They all look alike. When the Turks came they captured a whole company of South Koreans, were taking them in, and thought they were Chinese. |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||