|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||||

|

|

Richard E. EckerDowners Grove, IL - "The fact is, it is most unlikely that an agreement would have come nearly as early as it did had it not been for those GIs doggedly making the conflict too costly for Communist forces to continue." - Dick Ecker

|

||||||||||||||||

Table of Contents:Part OneConnecting the Dots*How One Unheralded Platoon of GIs Helped

End the War in Korea

|

|||||||||||||||||

The table of organization of every U.S. Army infantry regiment involved in fighting the war in Korea included a small group of technical specialists known as the counterfire Platoon. The mission of the men in this platoon was to provide information on the location of enemy weapons so that they could be neutralized by return fire. The method they employed was "sound ranging," so called because the sound of the muzzle blast of an enemy weapon was used to determine its location. Because the success of sound ranging equipment depends on the ability of the counterfire specialist to hear the muzzle blast when the weapon was fired, our observation posts (OPs) had to be located as far forward as the tactical situation would allow. And, because Old Baldy was an outpost more than a thousand yards forward of our front-line positions, it should have been an ideal location to listen for enemy weapons being fired. It should have been, but it wasn’t. A photo of Old Baldy, as it looked a couple of months later, is shown above. The elevation in the foreground was called Westview.

The main problem was background noise. When you are that far forward in a combat zone, the sounds of battle are always with you. Even though the specialist himself could often distinguish the blast of an enemy mortar or artillery piece through that noise, the equipment we used to pinpoint the sound could not. In addition, the alignment of the equipment, which was essential for accurate measurements, could be disturbed by heavy incoming fire—and incoming fire had been increasing steadily in recent days on Old Baldy. I’ll discuss more about all of that equipment later. For now it is sufficient to say that my counterfire OP out on Old Baldy was unable to do its work and I needed to move the men back to the MLR where, although farther away from the enemy gun positions, they were not so hampered by noise and incoming. That was my plea to the Regimental S2.

Fortunately, he agreed. As it turned out, it was a lot more fortunate than I had anticipated—particularly for my men from the Old Baldy OP. By about 1600 that afternoon, I had them off of the outpost and situated in a new OP back on the MLR. By midnight that night, it was being overrun by a horde of Chinese regulars.

At that time, Old Baldy was being occupied by the Colombian battalion that had been attached to the 31st as part of the United Nations mobilization for the war. Offering fire support for that sector of the front was the U.S. 57th Field Artillery Battalion, which had assigned as an artillery forward observer with the Colombians 2nd Lt. Albert De La Garza, Jr. from San Antonio, TX. The counterfire OP on Old Baldy had had a close relationship with Lt. De La Garza, because they were about the only Americans on the hill. So, we were all dismayed the next morning to hear that the forward observer was reported missing after the battle and was assumed to have been taken prisoner. That assumption was confirmed in the next few days, and it was also learned that he had been wounded in the assault. All of this, of course, would seem to have little bearing on the story…except for what happened a month later.

During the week of April 20 to 26, 1953, 149 sick or wounded U.S. POWs were returned by the Chinese in a prisoner exchange called Operation Little Switch. Lt. De La Garza was included in that exchange. Before being evacuated back to the States, he was debriefed by military intelligence. In his debriefing, the lieutenant recounted persistent interrogations by his captors. One of the questions they had badgered him to answer was, "What makes your counterfire so effective?" When news of the forward observer’s Chinese interrogation trickled down to the men of Bearcat Counterfire, we were delighted to hear that we had been giving them that much trouble. And we were pretty sure we knew what made them so upset.

It was common practice with the Chinese at that time to set up their weapons, fire off a few rounds and then quickly withdraw back into their caves. But, when a Chinese cannoneer pulled the lanyard on a weapon aimed in our direction, it was very possible that he would not live to pull it again—and his commanders would find devastation where he and their guns had once been. Three minutes. That’s how long it took—from the time a round from one of their guns impacted in our sector till we had six rounds of 105mm HE (high explosive) exploding on the weapon that fired it. What made so quick a response possible? Read on, and I’ll tell you

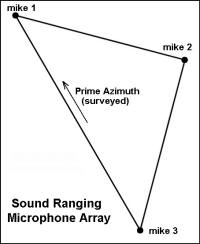

Successful sound ranging involved two key ingredients: 1) a highly skilled counterfire specialist; and 2) some very sophisticated (for that day) electronic equipment. To establish the direction to the source of a sound, you first need an array of three microphones set up in such a way that the sound wave would reach each of them at a slightly different time. These microphones were tied together so that, when one of them was fixed to the ground, the other two would stretch into an accurately-measured right isosceles triangle, such as the one in the illustration. The length along the key azimuth was about 20 feet.

Ideally that azimuth should be surveyed in, but circumstances seldom allowed that to be possible. The microphones needed to be out in the open where they had the best chance of picking up sounds from the direction of the enemy—which was usually in full view of their observers. So, to avoid allowing them to see where we were and what we were up to, we had to sacrifice survey precision in establishing the key azimuth. Most often, the direction of that arm of the array had to be determined by a sound ranging specialist on his belly in half-light using a GI compass. In fact, these expedient methods were usually very adequate, as the complaints from the Chinese testified.

The photograph below was taken in front of the counterfire OP bunker on the MLR to which the Old Baldy OP had been moved (OP#6). In the upper left corner you will see a microphone (mike #1) from the array for that OP. The two officers in the photo are the author (on your right) and his replacement as Counterfire Officer, Lt. John Nisbet.

Also visible in this photo are wires running from the microphones in the array into the bunker, where they were connected to equipment that would record and analyze the sounds. That equipment consisted of a closed-loop recorder and a "black box" containing electronics that converted the sounds into patterns on an oscilloscope. The recorder rotated a steel tape, repeating the cycle several times a minute. Each microphone in the array was connected to a recording head in the machine. Before any recording session, each head was positioned at a specified base position in the loop. Erasing heads were also in the loop, one immediately before each recording head, so that sounds were repeatedly recorded and erased as the tape rotated.

The recorder could be turned on and off by means of a thumb switch on a long cord that could extend well into the trench outside the bunker. When the recorder was turned on, it ran continuously, recording and erasing whatever was being picked up by the microphones. If, while it was on, the sound ranging specialist heard a muzzle blast from an enemy weapon, he had about five seconds to press the thumb switch to turn it off. If he waited longer, the sound would be erased from the recording loop.

Once a suspected muzzle sound was recorded on the tape, the "black box" in the bunker was put to work. In essence, here was what the process of analysis involved. Because the tape rotated at a specific speed, the location of each sound on the tape could be translated into a relative time that the sound reached each of the microphones. If you look at the layout of the array shown on the previous page, you can see that, whatever the direction from which the sound originated, the waves would hit the microphones at a predictable sequence of times. So, once the specialist had determined that sequence from the "black box," he could use a special circular slide rule to calculate the azimuth from the OP to the enemy gun that had fired the round.

It all seems simple enough, but in fact it was anything but simple. Even though, on the MLR, we were not subject to the volume of incoming we had experienced out on Old Baldy, our microphones could be easily thrown out of alignment by a near miss from a periodic round of harassing fire. Or, more often—and considerably more frustrating—they could be uprooted by a GI taking a shortcut over one of our hills at night. And background noise remained an irritating problem. However, the biggest demand on our resources—trying to keep the OPs up and running when we needed them—was the energy demand of the equipment.

The energy supply for our equipment came from a six-volt lead-acid storage battery—the same kind that were used at the time in our jeeps and trucks. Because the motors and vacuum-tube electronics in our system had such a high energy demand, we could not afford to waste energy waiting around with the equipment turned on hoping for the enemy to shoot something at us. Typically, the specialist had to wait till a weapon was active—usually after the first round hit the ground in our sector—to turn on the recorder and take up a listening position in the trench. Then, he had to wait till another round was fired to catch that muzzle blast on the recorder. If he caught a clear sound, he quickly set to work calculating the azimuth to the enemy gun…and then quickly turned off the equipment.

We usually maintained one extra battery in each of our front-line OPs. But, with six OPs extending across more than five thousand yards of MLR—and the only available charger located at our headquarters some ten miles to the rear, keeping power available to our OPs was a major logistical effort. Virtually every day, someone had to make a trip to provide a fresh battery—or other needed supplies—to one or more of the OPs. And, because all of our locations were on the highest elevations we could find, it meant a steep climb carrying a heavy battery on almost every trip. Clearly, effective sound ranging depended as much on physical endurance as it did on a trained ear and facility with the "black box."

Of course, even when the sound ranging specialist has done his job quickly and efficiently, all he has to show for it is a single azimuth—the direction from his OP to the active enemy gun. The weapon could be anywhere on that azimuth line. Obviously, additional information would be needed to find the exact location of the gun. To solve that problem, the Army field manual on sound ranging operations specified that counterfire OPs should be set up in pairs, with their electronics connected together such that the two recorders could be stopped together when a specialist in either OP heard the sound of an enemy weapon. In principle, that makes perfect sense. If two OPs, separated by 500-1000 yards, each calculated an azimuth to the same weapon after their microphones recorded the same muzzle blast, the two azimuth lines should intersect at the exact location of the weapon. Indeed, that was the way it was supposed to work…but it never did—at least for us it didn’t.

We tried a number of times to connect adjacent OPs together the way the field manual specified, but was just too difficult to maintain the integrity of the two communication lines required to make things work; one line connecting the recorders and another for voice communication so that the specialists could coordinate their efforts. We did occasionally get intersecting azimuths from two different OPs, but that was a matter of chance rather than intent. In fact, our success didn’t typically come from intersecting azimuths. It came from the intelligent use of intelligence (more about that later)…and from the way we were organized to do our work

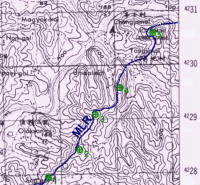

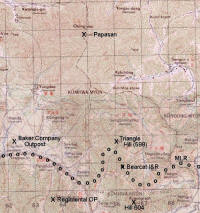

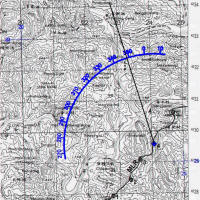

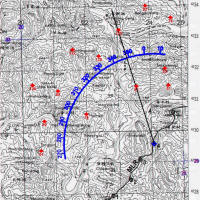

The adjoining graphic shows a topographic map of a portion of our sector, indicating the MLR and the locations of five of the six OPs. The sixth OP was featured in an earlier photo and is off this map to the northeast. The scale of the map is 1:50,000 and the distance in elevation between contour lines on this map is 20 meters (65.6 feet). Shown below is a photo of the author with the men from OP#1 outside the bunker that housed them and their equipment. The wires coming from the left in the photo lead from their microphone array on the crest of the hill above the bunker

Because of the relatively stable tactical situation in Korea during the War of the Hills, things could be organized to take maximum advantage of those circumstances. It was of particular advantage to the field artillery, because they were able to place their guns in specified positions and never move them. They could zero in every significant location within reach of their weapons and be dead accurate on any mission by using only map coordinates. In our division (the 7th Infantry Division), each of the three integral 105mm howitzer battalions was attached for tactical purposes to one of the division’s three regiments. The 57th FA Battalion was attached to the 31st Infantry and, because the business of regimental counterfire required an intimate relationship with the people on our side who could shoot back, Bearcat Counterfire was attached to the 57th.

Our operation was headquartered at the command post of the 57th, and it was there that we carried on support operations for the men in the OPs up front. It was there that we maintained our repair shop, battery chargers and supply stores. It was there that we maintained the personal gear of the men in the OPs, and a bunk for them to bed down when they were rotated off the hill for a couple of days of rest. That rotation policy was made necessary by the fact that our unit was never relieved from front-line duty—even when our regiment went back for a rest. To my knowledge, Bearcat Counterfire occupied those same OPs from the time the division took over that sector of the MLR till the armistice was signed some seven months later. And that was one of the wisest decisions the big brass ever made.

Being an effective sound ranging specialist was more than having a good ear and easy facility with the "black box." He had to know the terrain in front of him like the back of his hand. He had to know how different weapons sounded when they fired—and impacted—in that terrain. And he had to have a special feel for how the enemy in his sector carried on the business of making war. These abilities could only be acquired and maintained by spending extended periods of time in one place. Although, that might seem unfair, we really didn’t mind having permanent assignment to the front lines while the other GIs were getting periodic reserve time in the rear area. For us, there were sufficient benefits to our arrangement that no one ever complained.

|

|

For a primarily technical operation—one that thrived on a minimum of intrusion by the brass—ours was a situation made in heaven. We were an infantry outfit attached to the field artillery. We were orphans. The folks at regiment considered us to be the responsibility of the guys at the 57th, and they ignored us. The people at the 57th provided us a place for our headquarters and, otherwise, left us alone to do our work. I have always felt that this arrangement contributed significantly to our success doing that work.

The photograph on the right shows the view in front of OP#4. You can see from this photo (and from the topographic map of the region) that we had the advantage of ideal terrain for doing our work. There were no high mountains in the area to interfere with the sounds, and our observers had almost unlimited line-of-sight in all directions.

Operations at the 57th Field Artillery Battalion were carried on at the battalion fire direction center (FDC). Because of the stable tactical situation, fire direction operations for all three batteries in the battalion were performed there. The FDC bunker at the 57th housed the artillery fire direction specialists that calculated the parameters needed to aim their guns at targets requested by forward observers or others (like the counterfire platoon) that reported targets of opportunity. These specialists were supervised by the fire direction officer, who selected which missions to fire and then provided the initial data necessary for his crew to do their work…and a most remarkable crew they were. As I watched them over the months, I never ceased to be amazed at the speed and efficiency with which they calculated aiming solutions and communicated them to the guns.

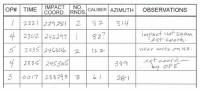

Next to the fire direction officer’s desk in the FDC, Bearcat Counterfire had its plotting center. It consisted of a switchboard (with lines to each of the OPs) and a large map table on which were affixed maps revealing the entire division front and all enemy terrain from which their weapons could reach our emplacements. Next to the switchboard was an erasable chart on which data from the OPs could be recorded. This chart was the first key in the business of "connecting the dots"…the intelligent use of intelligence. In that business, the prime credo was "no detail is unimportant!" An illustration of such a chart is shown below.

The Overlay Showing the Compass Arc from OP #4 (Click picture for a larger view) |

Without the regular ability to pinpoint the locations of enemy guns from intersecting sound-range azimuths, we had to use every bit of other intelligence we had available to do our job. A lot of critical intelligence appeared on the chart as the men in each OP reported what they saw and heard. It was the job of the people in the plotting center to sort through that intelligence—along with other sources of useful data—to determine whether or not we had sufficient reliable information to request a fire mission on an enemy weapon position.

The topographic map itself was our first source of useful information. Our map table was about five feet long and half that in width. The 1:25,000 scale maps on it covered everything we had to be able to locate on both sides of the MLR. On these maps, the locations of each of the OPs was indicated, so that what had been determined on the ground could be duplicated on the map. That is, if an azimuth had been calculated from an OP, the plotting center had to be able to reproduce that azimuth on the map. To make this possible, an arc was drawn on the map indicating compass directions from each of the OPs. (Click here to open the map with that overlay, showing the compass arc from OP#4)

To reproduce the azimuth on the map table without actually drawing on the map, we used an overlay of clear acetate with one side sufficiently rough that it would accept a pencil mark. With that overlay in place, and with a pin in the location of the OP reporting the azimuth, we drew a pencil line through the compass arc at the azimuth indicated. Somewhere on that line was the weapon we wanted to neutralize. However, unless we had an intersecting azimuth to the same weapon from another OP, we needed more information.

The Final Overlay Showing Suspected Enemy Weapon Locations (Click picture for a larger view) |

One source of possibly helpful information was sent every couple of days from Division G2 (Intelligence). This was an updated list showing the coordinates of known or suspected enemy artillery and mortar emplacements. I have mentioned that the Chinese tended to move their weapons frequently, so it was imperative that we continuously update our list with the most current data indicating their possible whereabouts. The data on this list included both the location and the most likely caliber of the weapon. These data came from aerial reconnaissance and a variety of other sources—including counterfire operations like ours. Whenever we located a weapon by sound ranging that was not on the G2 list, we reported it promptly for addition to the next update. Each time we received an update, the data were quickly added to a map overlay showing all known and suspected enemy weapon locations. (Click here to open the map including that overlay).

When this overlay was placed over the map and its first overlay, the one indicating the azimuth line reported by the OP, you could immediately see whether or not the line passed over the location of a known or suspected enemy weapon of the reported caliber. In our experience, it often did...as with the example azimuth on the OP#4 overlay. Very often, however, the azimuth line did not indicate any specified position for that caliber weapon. So we needed to draw on additional information. The contours on the map itself were often able to provide that information.

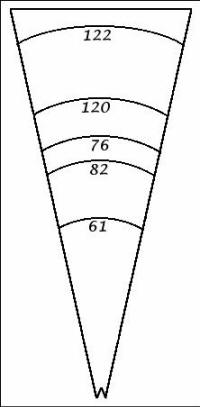

When you have been routinely reading topographic maps for months, the terrain indicated by the contour lines tends to jump out at you as if you were looking at it directly. So, when we were looking on the map for the possible location of an enemy gun emplacement, the contours could tell us sometimes where the most likely possibilities would be. To assist us in this endeavor, we needed one more kind of data—the maximum effective range of each of the weapons in the enemy’s arsenal. These figures we could obtain from division intelligence. Then, each of these distances was copied as an arc on a fan-shaped overlay using the same scale as the map on our plotting board. This overlay is illustrated in the graphic shown on the right. (Note: This illustration is not intended to represent the actual relationships among the ranges of the weapons indicated, but simply to demonstrate the construct of the overlay.)

To use this overlay, a pin was placed into the map board at the coordinates of the impact. Then, when the overlay was placed over the azimuth line to the enemy weapon, with its vertex at the pin, you could determine how much terrain along the line needed to be examined to find the possible location of that kind of weapon. In the terrain we were working in at the time, this was a useful exercise and occasionally gave us a likely target for our counterfire.

These were the collection of tools used by Bearcat Counterfire to connect the dots… to quickly locate where active enemy weapons were located and to eliminate them. In a conflict like the War of the Hills, the victor will most often be determined by which side is first to make the other pay too high a price to continue. That’s what we did in the final months of the war in Korea.

*A condensed version of this report was published in Military Heritage, February 2006, pp. 20-25. If you would like information on the book that gave birth to this story, see Friendly Fire.

Part Two

Bearcat I&R

When I published recollections of my experiences in the Korean War (Friendly Fire, Omega Communications 1996—see www.ocomm.org/fire), two-thirds of the book had to do with my first combat assignment; command of the Intelligence and Reconnaissance (I&R) Platoon of the U.S. 31st Infantry Regiment (code name Bearcat). It is not my intention here to reiterate stories included in that volume, although some of the characters and events may re-appear as bases for the added details that are the purpose of this essay. For a number of reasons, it was not possible—or practicable—to include some of those details in Friendly Fire. However, they appeared to me to comprise a story in themselves, so I undertake to describe them here.

I was inspired to take on this project after I read portions of a 1994 master’s thesis by Maj. Richard J. Runde, Jr., who was a student at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Ft. Leavenworth, KS. His thesis, titled The Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon, 1935-1965: Lost in Time, documented the history of the I&R platoon from its inception till it was eliminated as an active military unit. I will include a bit of that history here, but I intend to concentrate on how the Korean War really began the demise that terminated its existence in 1965.

As it was constituted during the Korean War, the I&R Platoon was actually a unit without a clear mission. That mission had developed out of experiences in WWII, during which the platoon evolved into a highly mobile element providing a regimental commander eyes and ears to the front and to the flanks as his regiment advanced into battle. By the time of the Korean War, that evolution had resulted in a platoon with eleven jeeps, 33 men, multitudes of communication equipment and scads of other stuff that even I cannot begin to recount for you. The reason I cannot is that I never identified most of it. My most vivid memory of it was as a huge, disorganized pile of miscellaneous equipment in the back of a squad tent.

I explained in Friendly Fire the details of my becoming the commander of Bearcat I&R. Here is how I described the assignment in my first letter home from Korea:

Finally made it. It took 24 days from the time I left till I took over my platoon.

But it’s a bit different type of platoon than I had anticipated. I am the 31st Regiment’s Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon leader. It’s an outfit organic to the regimental headquarters and does just what the name implies.

I had hoped to get such a position after I’d had some experience but I was quite surprised and I consider I was very lucky to get it…

Had the circumstances been different, there is no way that a raw 2nd lieutenant, fresh from the states, would ever have been given such an assignment. However, the current circumstances did not permit the I&R Platoon to be employed as the field manual (FM 7-40, Infantry Regiment) intended, so the qualifications of its commanding officer were not all that critical when I took command.

The evolution of the I&R Platoon described in Maj. Runde’s thesis created a unit that was a key element in the success of a regiment on the move. With eleven jeeps, all interconnected by radios, the platoon’s primary mission was to lead the point battalion in the move forward and to scout the flanks to maintain contact with adjacent elements or feel out possible enemy penetrations. However, by the last year of the Korean war (I arrived just as that year was beginning), none of the contesting units in the war was on the move. The battle lines were more reminiscent of the first World War, where the opposing forces occupied trenches and spent much of their time shooting artillery at one another.

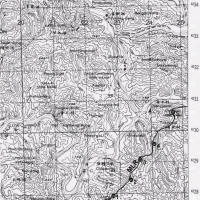

The MLR (Main Line of Resistance) in Korea when I arrived was a trench extending from border to border across the peninsula. Even if the tactical situation had been more fluid, the terrain in that country still would have prohibited the platoon from being employed as specified in the field manual. The nature of that terrain can be seen in the aerial photo below:

This photograph (taken by aerial forward observer Harry Darby in October 1952) shows some typical terrain along the MLR (Main Line of Resistance) in central Korea when I took over the I&R Platoon. The photo was taken looking to the northeast. The MLR is shown by the string of circles on the photo. At the far left, the MLR follows an abandoned railroad coming out of Kumhwa—once a prominent North Korean City. On the right, it trails off to the east. The lower elevation in the upper left of the photo is the Kumhwa Valley. It is probably as large an expanse of territory without mountains as you would find anywhere along the battle line at that time. So it is easy to see why it was not possible to employ the I&R Platoon as specified in the field manual. In fact, as I pointed out in Friendly Fire, when I took over the platoon, it was occupying a frontline position, shown by the “X” on the photo. A topographical map of the same general area is shown on the following page. As can be seen from these graphics, the enemy occupied the dominant terrain in this area, including Hill 1062—Papasan, the father of mountains.

I’ll recap here briefly why my platoon was attached to Easy Company, because it speaks to how regimental commanders, in the final months of the war, adjusted the missions of their I&R Platoons to fit with their own views on how such units could be employed to their best personal advantage. In Friendly Fire, I recounted my initial interview with the regimental commander when I reported for duty:

“In this regiment,” the colonel explained, “I have been using the I&R Platoon to perform specialized missions against the enemy—to infiltrate their positions, to gather intelligence and to capture prisoners who can tell us about their troop strengths and battle plans.”

At the time, I assumed that the obviously hazardous mission he had just explained to me was the reason he needed a new platoon leader. In a way, it was—but not in the way I expected.

According to reports I got from the men when I took over, Lt. Pertulla (my predecessor) had been sacked and transferred when he refused to sign a recommendation that the colonel receive a medal for his participation on a patrol carried out by the platoon a few days earlier. The men told me that the colonel didn’t even accompany the patrol all the way to the objective and that the lieutenant had insisted he didn’t deserve a medal. They also were certain that the platoon was sent up on the line with Easy Company to remove from the scene all reminders of that unpleasant affair. Whatever the reason, my platoon was now a front-line unit and, at least for the immediate future, I was a rifle platoon leader.

Thus began my tenure as commander of Bearcat I&R, five months of widely varying assignments, only a few of which were even slightly related to what the field manual specified for the unit. And those assignments were at the whim of two successive regimental commanders. At the time, there were some 20 U.S. Army infantry regiments involved in combat in Korea, each with an I&R Platoon. So, as I relate my own assignments over just five months (and two colonels), you can begin to imagine the different ways in which all of those platoons might have been employed by the multitudes of different commanders during that last year of the war. And, you can also begin to see, with infantry tactics evolving for wars to come, why this was the beginning of the end for I&R as it was initially conceived to be.

The one by-the-book assignment we retained over the months I was in command was the maintenance of regimental observation posts (OPs). That responsibility continued, whatever else we might be assigned to do. At the time I took command of the platoon, the regiment had just one OP on the MLR, shown on Hill 471 on the topographic map on page 3. So, when my platoon was exiled to Easy Company, I still had to have men from the platoon occupying that OP. In addition, an I&R platoon at the time was assigned a lot of equipment—particularly communications gear that was needed for the missions specified in the field manual. Every one of the eleven jeeps organic to the platoon had at least two radios; some had three. At the time, all of those radios, plus some automatic weapons and a lot of other equipment, occupied a huge pile in the back of a squad tent at regimental headquarters. That pile of equipment—plus the personal gear of the men in the platoon—needed to be guarded at all times. (Those two squad tents at regimental headquarters were where the I&R Platoon had permanent billets—while they were “temporarily” helping out up on the front lines.) So I had to have least one man from the platoon stationed back at regimental headquarters to secure the equipment.

Although I have suggested what some of that equipment was, I actually never had any idea what a complete inventory might be. I had signed for it, but I never counted it. It was not possible to count it; it would have taken days, which were not available. It appears that the man I replaced had no better idea than I concerning what was in the pile I had signed for. That was just the way things were done in Korea at that time. I fervently hoped that, when I left the platoon, my replacement would follow the same routine.

Our tenure with Easy Company was brief, only 11 days. However, while we were there, orders came down from regiment assigning our platoon to a combat patrol with a mission to capture a Chinese prisoner off of Hill 598 (Triangle). The colonel may have exiled us, but he hadn’t forgotten us. On that now infamous patrol—after which Lt. Pertulla had gotten the sack— the platoon had failed to capture a prisoner. Now he was giving us the opportunity to redeem ourselves. Fortunately, that opportunity was never realized. A few days after we received the order, we were pulled off the hill and moved about three miles to the west to occupy new positions on Baker company Outpost, shown at the far left on the aerial photo and map on pages 2 and 3.

Now, before I relate what we would be doing out on the outpost, I need to give you a little insight into the makeup of the platoon. As its organization was specified in the regulations, the assigned duties of most of the men in the platoon could be guessed without much prompting. With eleven jeeps, there had to be eleven drivers. Every jeep had at least two radios, so there had to be eleven radio operators—some of whom may have had other duties. The platoon consisted of three squads, each commanded by a squad leader. The command unit consisted of the platoon leader, a platoon sergeant and assistant platoon sergeant. That’s 28 out of 33 men. Among the other five, there had to be some intelligence specialists. And, there was at least one fifty caliber machine gun in that pile of stuff at regimental headquarters (and at least one of the jeeps was equipped with a post to mount a machine gun), so at least one weapons specialist was probably included in the Table of Organization (TO).

I can only speculate what that TO might have looked like because we were never employed in the way it specified and none of the men in the platoon (except the drivers and my radio operator) had any specialized training. Not only that, six of the men in the platoon were KATUSAs (Korean soldiers), none of whom could speak much English—and one Korean civilian interpreter. So, Bearcat I&R in September of 1952 was a bastard outfit that the colonel felt comfortable assigning to any miserable job that came along. Given that, we could anticipate that, if we were being relieved of the task of trying to grab prisoner off of Hill 598, then the new job the colonel had in mind for us was not going to be a walk in the park. It wasn’t.

On the aerial photo and the map, Baker Company outpost appears to be little more than a blemish on the landscape of the Kumhwa valley. However, you need to be reminded that every one of those contour lines on the map represents twenty meters (65.6 feet) in elevation. So, that blemish actually rises over 150 feet off the valley floor. A deep trench circled the crest of that hill and a full, reinforced company occupied bunkers along that trench. It was a veritable fortress. However, Bearcat I&R was not destined to gain any benefit from that fortress because we were being assigned to occupy positions outside the outpost, extending several hundred yards out into the valley to the East. Our orders were to dig foxholes out there and occupy them ever night on one hundred percent alert. We would sleep during the day in an old, abandoned tank bunker, a couple hundred yards to the rear. Our mission was to detect any possible enemy penetrations into the valley at night, call in fire on them and bug out (if we were lucky). This was not really an intelligence assignment, but it was typical of what this colonel was inclined to do with his I&R Platoon.

We never detected any significant enemy penetrations and, after thirteen days out there, the regiment was ordered into division reserve. An infantry division in Korea typically consisted of three regiments, only two of which would be committed to front-line duty. The third regiment would be “in reserve” at a location well back from the MLR—but not so far that it couldn’t be quickly mobilized to reinforce a front-line unit that got into trouble. Typically, the reserve regiment would be involved in training, where the environment was more hospitable to that activity. Here is how I described my reserve experience in a letter home on October 3, 1952 some two weeks after we came off the line:

…This reserve is great stuff. Regular hours, training instead of dodging artillery, a fine officers club—plenty of booze, movies (if you can stand the 31st outdoor movie in this weather—it gets down to 40° F here at night now). Winter soon…

In a letter twenty days later, I filled in the folks back home on details of my activities after the regiment went into reserve:

…I just had my first week’s training schedule figured out when someone got the bright idea to move in and evict the Chinese from a bit of real estate called Triangle Hill. So I had to cancel my training and start working on observation posts for the operation (one of the jobs of an I&R platoon is to construct and maintain OPs for the regiment)…

My explanation in this letter makes the building of OPs sound pretty routine. It wasn’t— particularly when the OP we had to build was up on Hill 604 (1975 ft.). The regimental OP on Hill 471 was too far to the west to be able to see all of the objectives. So, the colonel needed a new one, where he could watch the festivities from a more advantageous location. The problem for us (Bearcat I&R) was that Hill 604 was a very steep elevation and you could only drive a small fraction up the side of it. After that, it was a 45-minute hike up to the crest. I won’t detail all of our experiences up on 604. I did that in Friendly Fire. All we managed to complete was a hole in the ground on the top of the hill, and then we were pulled off. However, the OP was completed before the battle so I assumed they must have brought in the engineers to finish the job.

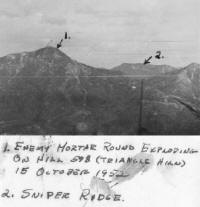

During the battle, which began on October 15, 1952, I assigned I&R personnel to man the new OP and I was assigned to be a liaison officer with the regiment that had replaced us on the line a few weeks earlier. I watched the battle from their regimental OP on Hill 471—the one we had occupied before being relieved. This is a photo I took that day from my position in that OP. The two identifying comments were written on the back of the photo when I sent it home. Sniper Ridge, an enemy held position, can be seen in the aerial photo on page 2. It is the easternmost ridge in that photo. I can’t recall now where the rest of my platoon was located during the battle. Because we were well supplied with jeeps, we were always called upon to provide taxi service for the regimental staff, so I expect a lot of them were doing that. Whatever they were doing, we were all happy not to be up on that hill, where casualties in the regiment were the worst for any one day during the entire war.

By the second day of the battle, the division commander relieved our colonel from command of the operation and our regiment was sent to replace the front-line regiment on the west of the division sector. That regiment was then committed to the battle in our place. The following day, Bearcat I&R was sent up to reinforce Item Company which had been badly shot- up on Triangle. For the next 26 days we were again a rifle platoon—although ours was a rather meager contribution to the effort because we still had platoon members assigned as drivers and observers. The front-line position we occupied this time was the closest friendly position to King Company Outpost, a hotly-contested hill a few hundred yards forward of the MLR.

|

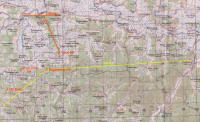

The map below shows most of the western sector of the division front. I have included Baker company outpost on the map to show how this sector connects with the map on page 3. The MLR over all but the most western area is just an estimate. Item Company occupied the far western end of the division sector. Out platoon position was in the middle of the company sector. The primary enemy position in our area was Star Hill. We observed many attacks from it directed on the outpost. We had front-row seats to all the action out there—but we also got a lot of covering fire from the Chinese when things got hot. Here is how I described it in a letter home:

“…and more Chink artillery than I ever knew existed. Man, they can pour that stuff in.

One night when the reds were trying to take over a little hill on our flank they dropped in almost 3,000 rounds in our company area in less than an hour. For 20 minutes I couldn’t even get out of my bunker to get down on the line with my boys. Not a man was even seriously wounded in the entire company that night. Just a few scratches…”

On the 11th of November, we were moved off “the hill” and back to regimental headquarters. The whole division was preparing to move back into Corps reserve. I assume that we were involved in guiding regimental units into their rear area locations, but I don’t recall any details. In the reserve area, Bearcat I&R was involved in two kinds of activities: training and rear area patrols. The new colonel (the old one had been relieved soon after the Triangle Hill fiasco) had decided to make us into a regimental police force. The primary offenders were Korean prostitutes, although bootleggers ran a close second. What I remember most about the training was the effort by the regimental communication officer to help us resurrect radios out of that pile of stuff we had been storing and to learn how to use them as the book specified for an I&R platoon.

We did get a commendation from the colonel for “maintaining order in the regimental area” during the weeks we were in reserve, but all of our training really went for naught because the platoon was caught stealing the regimental beer ration and most of the men were shipped out to line companies as punishment. When the regiment went back up on the line the day after Christmas, the I&R Platoon guided the units into their new locations, but all be two of them (my driver and my radio operator) were new men without any specific training for I&R business.

The new regimental area was off to the west of the position we had been in just prior to being called into reserve. The map below shows the west end of that sector. I don’t recall the specific track of the MLR in that region, but I have identified the general area in which Bearcat I&R occupied regimental OPs while we were in that sector. I had thought there were just four of them, but I mentioned in one letter home that I had 14 men stationed on OPs, so there may have been more than four because I wouldn’t have had more than three men on each. I do recall the location of one of them, because that is where I was during Operation Smack on January 25, 1953.

As I described it in Friendly Fire, Operation Smack was a big show for the big brass. (Note: In the book, I placed the date of the operation later in the war, but my recollections of the details are quite accurate.) Spud Hill, an elevation at the south end of a Chinese-held complex called T-Bone, was an ideal location for such an operation. It was small, somewhat isolated from other enemy positions and it was observable from locations all along our MLR. After all, if they were going to have a big show, they needed plenty of front row seats for the big brass. And, who currently occupied those front-row seats? Bearcat I&R. In addition, with eleven jeeps and drivers at our disposal, we were the ideal choice to transport the UN brass to the festivities. So the part to be played by my platoon in the big show was to pick up general officers and deliver them to the front, where they would be welcomed by the I&R occupants of the regimental OPs.

My own part in the festivities was similar, but with an officer of considerably lower rank, and who had a very different interest in the battle. I had to escort an Air Force public relations officer and his photographer to the OP shown on the map above and to answer any questions he might have about what was going on on the ground. They were there to take motion pictures of Air Force jets as they made bombing runs on the objective before the assault. Details of this costly— and failed—attack can be found in Friendly Fire, but I will add here some casualty figures I did not have when the book was written. Of the two companies committed to the action, five men were killed and 52 wounded, ten of them seriously enough to require evacuation to the States.

Ever since the regiment was returned to the fighting the day after Christmas, I had been burdened with increasingly time-consuming extra duties at regimental headquarters, and often I had been required to send my men out on assignments under the command of my platoon sergeant. None of those were combat assignments (among other things, we were still responsible for chasing down prostitutes), but I didn’t like it and I finally requested a transfer. So, about two weeks after Operation Smack, I received orders transferring me to command of the regimental Counterfire Platoon. Thus ended my five months as commander of Bearcat I&R. It was a unique experience—and I expect, if you could poll the dozens of other I&R commanders during the war, you would find their testimonies just as unique…and just as confirming of the proposition that this war was the beginning of the end for the I&R Platoon,

Richard E. Ecker, Ph.D.

Downers Grove, IL

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | back to top |

|

| Contact | What's New | About Us | Korean War Topics | Support | Links | Memoirs | Buddy Search | |

|

|

© 2002-2012 Korean War Educator. All rights reserved. Unauthorized use of material is prohibited. |

|

|

- Contact Webmaster with

questions or comments related to web site layout. |

|