|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||

|

|

Bill R. CrumNewman, IL- "During the fighting were we afraid? Yes, definitely afraid. Did we dwell on the fact that we might not come back? No, you always had that fear that you may not come back. This was in your mind because death was around you all of the time." - Bill R. Crum

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| We have lived in Newman since 1972 on City Line Road. Our post office address is P.O. Box 66 I

grew up in Mt. Carmel, Illinois and went to school there and graduated from high school in 1945. After graduation

I worked, and then I went to Southern Illinois University for a year. Then I worked a year at the Flint Coat, it

was a roofing factory. We made roofing. I married Joella Imbler and then went to Eastern Illinois University for

my next three years where I studied Physical Education and Mathematics and became a secondary teacher and coach. I was employed at Villa Grove High School, as a math teacher and football, basketball coach and we were there until I was drafted into the service for the Korean War. I finished the school year. It would have been June, I guess June of 1952. I didn’t know much about Korea. I knew approximately where it was but nothing about it. I took my physical in 1946 for World War II and the war was over then. So I was never drafted then but I was kept on the records and was …. well since I was a teacher and in school I wasn’t drafted early into the Korean War. I was about twenty-two when I went overseas. My basic training was at Ft. Riley, Kansas. Joella came out after I got through with basic as I went to a supply school in Ft. Riley Kansas. We lived there until I was shipped over seas. She moved back with her folks in Mt. Carmel, and she lived there. I probably was a week in Mt. Carmel before my papers came and then I went to Washington, the State of Washington, and shipped out from there. I went to Japan first by ship. I got seasick. Not the whole time, but quite a bit, yes. It was rough. When we landed I did not know anyone but it was a new adventure and had to take it as it came. From Japan we went to Korea by boat. The boat was a transport, which was much smaller than the boat we came in from Washington. The ship over from Washington was the SS Brewster. We landed at Inchon. I did not have much of an impression of Korea at first because it was night when we landed and then we were put on a train and you couldn’t see anything. I mean there was nothing, it was night when we went in and there was nothing really to see. I arrived on the first of February, 1953. We thought we were being assigned to 31st but we were shipped into the 2nd Infantry Division but we thought we were going to the 7th. Then they found out we were suppose to go to the 7th and after three or four days we were then transferred into the 7th. The 7th was on the front lines.

The 7th as in the north. We were on, I think Hill 347. If that means anything, and which is real close to Old Baldy which Old Baldy is in the vicinity of Pork Chop Hill . They’re all kind of in a triangle there together. The day we came in there were artillery rounds coming in and there was patrol out. The first night I was assigned to communications (Commo), it wasn’t supply, I was in Commo now. In Commo, you worked, first you have the telephone where you transfer all the calls, and you have a board and transfer calls, like to the company commander or where ever. Incoming calls and out going calls. We had to work that then all the communication lines which were by wire. If one goes out, like if a round comes in and knocks out a line down to say platoon one; then your job is to go out and fix that line and repair it or put in a new one. If rounds were coming in we usually put in a new one rather than try to find where it was knocked out. We’d just run a new line from Commo out to the first platoon and hook it in. We were also in charge of radios and we would be assigned to a patrol we would take care of taking the radio on patrols. I was a trained supply clerk but they just needed communications people up on the front line if they get short in any areas they’re going to put you in those areas, irregardless of what you are trained to be. They were short of commo at that time so that’s where I was put and I learned as I went along. We ran those communications lines out under fire. That was our job. Our job was to make sure communications were taken care of regardless of what was coming or going. It was a very hazardous job as far as infantry was concerned because we were exposed to enemy fire, not necessarily small arms fire, but any artillery coming in on our position. We were armed with carbines, we had flak jackets which are somewhat like a bullet proof vest, and of course our steel helmets, but that was all. The flak jackets would protect you, but you had nothing on your legs or on your face or this type of thing. Our carbine was our only arm and the reason we carried a carbine was in case we met Chinese, on patrol. We at least would be able to protect ourselves. But we could not do anything as far as incoming artillery. We did lose some people. We had about 8 or 10 in our Commo when I went into Commo; in Item (I) company and probably out of those eight there were three that came through that unwounded. I was one of the three. Two died from shrapnel where they got hit. We laid wire on the ground and through the trenches that were six foot deep that we moved in and we laid this wire in the trenches, which helped. It wasn’t real heavy to carry. It was on a spool and you unwound it as you went. The equipment on either end of the wire was the telephones. We hooked it into the switchboard and it went out to the telephones in the first platoon, the CO, the 2nd platoon, 3rd platoon, 4th platoon. On patrols a lot of times, we might string wire to the 1st platoon then out to a patrol that would set up a waiting patrol. We would string wire out to them, which they also had radios too.

Artillery was the big problem on line damage. If in coming rounds hit close by or shrapnel hit it, it knocked it out, and then we had to repair it or replace it. And then a lot of times when rounds were coming in which, at night or such, you would never get it repaired, you would just replace it and run wire again. Keeping communications open was very important because you were at least able to contact someone maybe a half or quarter of a mile down in the trenches, set up on one side. The CO could contact them if the Chinese were moving in their direction, you could get word back to the CO, "hey we’ve got Chinese coming up our flank here, get artillery at such and such a position." Communications were very important and it helped saved lives and it at least let everybody knew what was going on. It wasn’t always hazardous because they didn’t throw rounds at us all of the time. Probably, oh the worst part, was when we first we went up to take Pork Chop back, our company did and this was a very trying time as far as radio communication of this type was concerned. Then when we took Pork Chop back and were established there our job was to put in all new lines on Pork Chop hill which was torn completely up because our, our artillery and the Chinese artillery had been coming in on Pork Chop. We were in 347 then we went to what we called blocking position, then we went on counter attack for Pork Chop Hill then were up on Pork Chop Hill, I think 17 days. We were in what we called tent area, reserve, and if something happens you’re called up to support whatever company is overrun. At this particular time which was in March of 1953, Pork Chop was overrun; I’m not for sure who was up there then. I think it might have been Easy Company but I’m not for sure and we had to go back with King and Love Company and try to take it back. In other words the Chinese were in control of the hill, but we went back up. The Peace Talks had started but nothing had been done at this time. The Chinese at that time were trying to make a point that they can take whatever they want. Then we spent 17 or 18 days on Pork Chop Hill. Those 17 or 18 days were very, very tough days. We had a lot of soldiers that were even shooting themselves to get off of the hill. They would shoot themselves in the hand or the leg just to get off of the hill because they were afraid they were going to be killed. During one of those days the Chinese attacked us and they got into our trenches and we had what we called flash Pork Chop. Our own artillery came in on our positions. We barricaded ourselves in our bunkers to keep away from the artillery and the artillery was so heavy that it forced the Chinese off of Pork Chop Hill that night. The next morning there was just a lot of dead Chinese in our trenches and all around. That day we rolled the dead Chinese over the hill down toward the valley and the next night the Chinese came and picked up their dead and took them back to their lines. All there was really between Pork Chop Hill and the Chinese was a valley. We were on one hill and they were on the other hill. Pork Chop Hill was more like the hills of Southern Illinois. I mean their not real, real tall mountains. It was a good size hill but it kind of went out in a finger coming off and I guess the reason they called it Pork Chop Hill, it was kind of shaped like a pork chop. It came in like a finger and the widened out there at the top. It was a strategic point for the valley of the Chinese where they could come through. They could get through to infiltrate our lines on back and that’s the reason we controlled Pork Chop Hill. We lost a lot of men up there trying to defend it and keep it. During those seventeen days of heavy fighting, we were laying our lines. We maintained the lines and kept radio control going. We also would put one man out on all of the patrols, which you would go at night on patrols out into the valley to see if any Chinese were out there. You were the main one to let people on Pork Chop know there’s Chinese moving in our direction or this type of thing. These patrols were like sitting ducks. Some of them didn’t come back, that’s true. I was in the fighting sometimes. I was protecting myself but my job was not really as far as fighting was concerned but when they overran us yes, I was using a carbine and trying to protect myself. It was during the 17 days, I’m not for sure the date in there that they overran us but it was within those 17 days. It was between March 25th and April 14th that they overran us and we had what they called flash Pork Chop where our own artillery was thrown in on our positions and it saved our lives really. Flash Pork Chop is when we asked for the fire to come in on us to save the position and ourselves. Sometimes friendly fire hurt us. Especially, I know this was true later in our work, we had to take back another hill which was called, Dale Outpost which we took back was in proximity to Pork Chop. Dale Outpost we were called out, it was probably 2:30 or 3:00 in the morning, which was dark and we were lined up ready to attack the hill and rounds were coming in and they were our own rounds coming in very short and hitting close to where we were. I think possibly they were whenever we went in counter attack to take the hill back there were probably some of our own soldiers that was killed by our own artillery because it was being thrown on the Chinese that had taken this hill. Now when we went on counter attack. I was mainly carrying a radio and my job was to stay close to our company commander so he could give orders to 1st platoon and 2nd platoon to the lieutenants that were in charge. We had several company commanders. Lt. Hemphill was with us when we took back Dale Outpost and he was wounded and received a purple heart and he is now, well he’s probably retired now but he was a Lieutenant then and went clear up to a General. I’m sure he was in Viet Nam and the whole bit. We had a company commander named Stephens. I think we had three or four. During that stint and the reason, they were wounded or they got shipped out. They went back to regiment or where they had a better job, in other words where they weren’t in combat. Mainly they were Lieutenants. Most of them were not too experienced. Most of them were fresh out of West Point or somewhere where they’ve taken their training to be an officer. Most of them were younger than what I was. Most of the men were younger than what I was. I was probably one of the older men. Now we did have a Sergeant that was in WWII that of course was older than what I was. He was one of our leaders. Most of the Chinese were young. As to their fighting abilities, it was hard to tell how good they were because their philosophy was, they blew the bugles, they charge and you don’t know whether they were doped up or what, they came and they came in droves but what I found, once we went back after them, they ran. Now whether they were told to retreat or not, I don’t know but they didn’t stay really and fight to the bitter end. I guess the bugle was their inspiration. Then they played American music to us and, tried to get us to surrender and, this type of thing. They had a lady that tried to be very romantic and get you come across and they would give you this and we’ll give you that.

The Chinese strategy was to overrun their objective. They will overrun you by numbers. In other words they would send a thousand Chinese up to your hill to try to take it back. They carried their Chinese Burp Guns; they had grenades, and Molotov cocktails. Yes they were very well armed. This was in February of 1953 and it was very cold. We had big parkas with hoods with fur, insulated boots and you tried to get on as much cover as you could, it was very snowy and it was miserable. It was heavy snow, not a blizzard but it was heavy when it snowed. It was pretty hard to keep clean in the front lines. They brought water. We had communications from the rear and they brought hot food up to our chow bunker that we could go down to. When it was heavy fighting, you’d go for maybe 4 or 5 days and you had C rations. Just a little tin can with maybe Spam, this type of thing. Spam was primarily what was in your C ration. The Chow Bunker was in the back of the hill, away from where the Chinese couldn’t see it. We had water that was brought in. We sponged bathed since we had no showers. During the fighting were we afraid? Yes, definitely afraid. Did we dwell on the fact that we might not come back? No, you always had that fear that you may not come back. This was in your mind because death was around you all of the time. Some of your buddies was wounded or killed while you were there. Like the 17 days we were on Pork Chop or the 10 days we were on Dale Outpost, which were trying times. We had one thought that probably we, a lot of us wouldn’t come back. This was during the time before we took Dale Outpost back and we were scheduled to run a counter attack on Old Baldy, which the Chinese held. We gave it up and they took it over. Somebody had the brilliant idea that we should take Old Baldy back and our company was selected to up and take over. We were to the place where we were loaded in the truck to transport us up to our jumping off point to take Old Baldy back. They cancelled it! That time definitely we took our billfolds and personal items and gave them to the supply sergeant because they, there probably wouldn’t have been many of us come back if we went in on that mission. We didn’t talk much about it. It was on everybody’s mind but you didn’t talk too much about it. I tried to keep a positive attitude about everything we were doing. A lot of our guys, not a lot, but there were guys that were very scared and sometimes they didn’t get their jobs done. I mean as far as Commo was concerned and that was bad because somebody else had to go out and do the job that they didn’t get done. You could understand but then you didn’t feel like they were doing their job. If they were letting your unit down, but then again you could understand why. Now you would look at it and you could understand why, they were scared and wouldn’t go ahead and do the job. Actually they could’ve been court martialed over some of their actions. The ones who shot themselves to get out of the lines were disgraced. I’m sure they got court martialed. But the court martial would be better than dying on Pork Chop Hill. They felt that way. They felt very much that way. They would rather take their chances with court martial than die. And that’s about what it would amount to.

There weren’t any stupid mistakes that I recall. Everybody was pretty careful about what they were doing and it was a job. You had something you had to do and you performed it and it was life or death. You pretty well took care of what had to be done. We were told to be careful in these mined areas because there were land mines in there but you had no way of knowing when you were out in a valley between the Chinese and Americans. If you were on patrol out there you had no way of knowing, especially at night, when you could run into a land mine. But you didn’t have any way of knowing; you were just lucky you didn’t run into something like that. I received mail from my wife and packages of cookies and this type of thing. Mainly it was cookies and this type of thing. The cookies usually were OK but a lot of times they would be crumbly. The mail was pretty good. They kept the mail coming and going. We were on the front line we still had communications by truck back to the rear and coming up to the front lines.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

||

|

(Click a picture for a larger view) |

||

On another patrol I was on we had a 6 man combat patrol out in the valley between Pork Chop and Chink Baldy. About 100 Chinese passed within 10 yards of where we were but our C.O. said let them pass as we were badly outnumbered.

Another incident which happened while on Pork Chop was when the Chinese attacked our positions and got into our trenches. Our C.O. called for Flash Pork Chop and our own artillery fired on our positions. It was very successful as it drove the Chinese back to their positions. They had a Chinese gal on a loud speaker playing our favorite American tunes and trying to get us to give up and come over to their side.

I was the happiest guy going when we moved off Pork Chop and didn’t think we would get off of this hill alive because it was so rough.

Outpost Dale, July 23, 1953

We moved from Pork Chop Hill to a blocking position for Dale Outpost, the closest hill to the Chinese bunkers. While there we had 3 big events happen; first, we were called to take back Dale Outpost as the Chinese overran it while Baker Co. was there. This event is part of the book, Pork Chop Hill. The next event was Item Company was called to take back Old Baldy from the Chinese. We were to ride in jeeps and trucks as far as we could. I was to ride in the lead jeep with our C.O. as his radioman for him. This was a suicide mission and probably none of us would make it back as the Chinese were dug in now on top of Old Baldy. We had turned in our billfolds to supply to send home if we didn’t make it back. We were to leave the tent area at 11:00 pm and attack time was 12:00 pm. I had my radio with me and our C.O. was in the jeep ready to go when we received word from Regiment that the attack was called off.

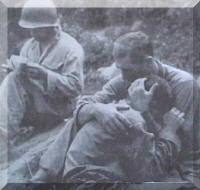

Probably the most difficult thing was when we had to counter attack as far as the hills were concerned and probably one of the most difficult times we had was when Dale Outpost was overrun by the Chinese, Baker Company was out there, we were in blocking but we had to run a line from our position, from our CP out to Dale Outpost where Baker Company was and they were in the midst of being attacked by the Chinese and there were five of us in the trench going out. We had our spool of wire and there were three of us from Commo, two infantry men with us on patrol. But as we were coming down the trench there were two engineers that were coming back off of the hill and they told us, now you don’t want to go out there. They said it’s Hell out there. You don’t want to go out there and of course I was the Sergeant then, I was in charge and I said Hey, we’re going. Well they had gotten past us in the trench and we were just starting to move out again when an enemy round come in and hit right on the second person, killed him, I was the lead man, I didn’t get hurt but the third man was wounded seriously, the fourth one was hit, I think in the arm,

The one that was seriously hurt was Wally Haines who recently, well within the past two years, has passed away. Primarily I’m sure part of his problems was from shrapnel that he had in his body. But anyway the medic came; this Eddie Cox came out after they heard that we were hit. I guess I’m not for sure whether the two guys that went by us told them back at our company headquarters that we got hit or what but anyway somehow they knew we got hit. He came out and this part I really don’t remember I’m sure that I had probably gotten a concussion because the round hit right real close to where I was but anyway He took Wally back to the rear and saved his life then and I took the wire and went out to Baker Company alone and installed the wire so we had communications.

I was awarded the Bronze Star for that. For Valor but that part was a little fuzzy because as I said, I’m sure I probably had a concussion and I don’t really remember what actually happened at that time. I would like to but I really don’t but Eddie says that I was there when he got out there with Wally when he picked up Wally I was there at that time. So I must have stayed there with Wally till he came out, then I took the wire on out to the outpost. Then the company commander from our company gave me a direct order to stay at Baker Company till morning. That was night we were doing this stuff. That was probably one of the most fearful things that one of our patrols that we were on. We had others but that one involved somebody getting killed, involved somebody getting seriously wounded, another was wounded but not as bad and the person that was in our outfit Commo that was wounded.

I saw many men do brave things that saved other men’s lives. Eddie Cox was one of them. The medic. I mean he was very active and went out of his way to help people that was wounded and was out, he went on a lot of patrols and patrols were dangerous. You were going out between the Chinese Line and our lines and you were exposing yourself to the enemy. Eddie was just there. I don’t, he probably was, really because actually really I don’t think he would have been required to go on patrols. But he did.

There wasn’t much time for laughter. We did have some cut-ups; we had them even in Commo. There was always somebody that was always cutting up. There was not much time for laughter or fun especially in our outfit because you were constantly working. You were pretty much on the goal all of the time. When you did get a little chance you crawled in the bunk and slept a little bit. There wasn’t a lot of time for horsing around on the front line.

We did get R&R once. We were given, I think three days of R & R, but that was when we were in blocking position. It wasn’t when we were on the front line. We went to Japan for three days. We just sight seeing and had meals and you know it was just to get away from the front line.

We had USO shows but no big names.

On the day the peace treaty was signed we were on Dale Outpost and the Chinese had put up all kinds of banners up on their hills and we were up, several guys had binoculars and were looking at the Chinese but that was what we were looking at. And then we had some fellows that got in trouble by going over to the Chinese lines.

On the day before the cease-fire there was heavy fighting. They just wanted to make their point that we can take this; we can take that that type of thing.

On the day of the cease fire there was rejoicing, oh yes, by Americans. I’m sure there probably was by the Chinese too. Still, there was nowhere to go. You were there and you were going to stay there until something was done as far as the pulling back and this type of thing. We were probably there two weeks after the cease-fire, then we pulled back into the tent areas and then we were there from probably August until we rotated in December of 1953. From August to December we were primarily just soldiers again, in other words we were still in charge of Commo so we took care of radios and the lines and this type of thing but we went back to soldiering.

After this cease-fire some groups were assigned to gather up equipment that was scattered here and there. We didn’t, but there were a lot of groups like the bomb squads that went in to try to take care of the bombs and this type of thing, the mines and try to work with them. But as far as equipment, any equipment that was out there was ruined; it wasn’t worth even trying to save because it was bombed and everything else.

We didn’t associate with the Korean civilians. Some officers had Korean houseboys but the enlisted men or the common man did not. But there were Koreans around but you didn’t know, a lot of them you didn’t know if they were giving signals back to North Koreans or not. There wasn’t anyway you would know.

Korea was not a nice place, it wasn’t a pretty country. Now maybe to some people it was but it was a land of, well the people were very poor and their living standards were very, very low. They had no sanitation and they had food that to me wasn’t fit to eat but they did.

Their latrines were bad, then they would take the filth from the latrines and put it on their gardens for fertilizer and that was very unpleasant to see a smell. They told us not to eat any vegetables that were grown in Korea so we didn’t. It was very unsanitary and the people were poor, they had to work, the women worked in the rice patties. They continued to work the filed and paddies during the fighting but not on the front line but in back in the rear. They grew their rice. That was the only source of food they had to keep growing rice.

We accumulated points and then of course after the war was over they lessened the points that you had to have. The longer you were on the front line the more points you accumulated for rotation. I was sent back to California. We then went to Chicago and then to Vincennes by train. No I think they met me in Vincennes, Indiana I believe. I took a train from Chicago to Vincennes and got off there. It was a very happy homecoming.

I’m sure Korea changed me. It made me more aware of what was going on in the world, than if I hadn’t been there. It probably made me feel that I was lucky that I came back in one piece, since I’d seen so many of my buddies wounded or killed in battle it made me feel well somebody’s looking over me or something I was am not a real religious person. I believe in God and I go to church but not real religious. Not a fanatic at all.

I understood why we were there. We were there to try to keep the Communist for taking over South Korea, and the Communist were in North Korea and it’s still going on today. It’s still there so I guess, yes we did accomplish that much, and we did keep South Korea from going Communist. Because if we hadn’t been there the whole state of Korea would be Communist right now. There’s no question about it. Because that was the North Korean objective. They were going to take South Korea over and so I guess we did accomplish that much. We didn’t fight it as a war that we’re going to conquer something. I’m sure we could have if we had really put our will to it and said, we’re going to drive you clear out of North Korea, we could have done that. In other words we could have probably occupied all of Korea now if we had wanted to. But that wasn’t the objective. The objective was we’re going to maintain South Korea, and we did do that.

I pretty push my war experiences out of my mind; I’m not one that wants to forget it. In other words I enjoy being around the men that I served with and we get together probably once a year and it’s to me an enjoyable time. I’m willing to talk about it and talk about my experiences. Some guys won’t.

Joella and I have three children, two boys and a girl. I think they understand what I went through. Do they understand freedom? Yes, I think they understand but a lot of people don’t know what the cost of freedom actually is. The guys that have been in the service, some have given their lives so that we can be free and that’s kind of taken for granted. I suppose they take freedom somewhat for granted to a certain extent. I mean, they’re thankful that it’s there but still I’m sure a lot of people don’t understand the sacrifices that a lot of people went through. There are so many veterans, they’re overlooked, and they really are. Especially the disabled ones.

The Korean War is called the forgotten war. I’d say that in a lot of cases, it didn’t really mean much to them. Now people that had people there it’s not a forgotten war but to the other people, it’s so what. But WWII wasn’t so. .No but it was one that was involved a lot more that Korea and the same way with Viet Nam. Viet Nam is just kind of pushed aside really, and there was a lot of boys that gave their lives in Viet Name, there really was. I would hope in the future that people remember the United States was involved and there was a lot of people that gave their lives for freedom so that the country of South Korea would be free from Communism and that it was not in vain that the Korean War happened. There was something gained by it for the United States and it was a bloody battle and the people that were there did a lot of suffering.

I went back to Villa Grove and was there until 1969 and then we moved to Florida for three years and I taught in Florida, then came back to Newman in 1972 and taught in Newman from 1972 to 1983 and retired in Newman in 1983 from teaching.

I’m active in 7th division and they have a meeting every other year and we went to Little Rock and California and we went to Minneapolis. We’ve been to three and hopefully we’ll get to go to Colorado Springs, we’re looking forward to it next spring.

7th Division in Korea

When the Korean conflict erupted in June of 1950, the 7th was under the command of Major General David Goodwin Barr. Barr assembled his Division at Camp Fuji, the tent city on the lower slopes of Fujiyama, and put them through a rigorous training schedule. The Division, which had sent several levies of replacements to the fighting front, was woefully under strength; consequently, 8,000 Republic of Korea soldiers were integrated into its ranks. This was a far from an ideal solution, but it was the best that could be reached under the circumstances. The ROK soldiers were willing and resourceful--and later they .showed themselves to be courageous as well. But the language barrier was too much to overcome completely. They had to be taught not only to obey commands, but also to understand what the commands meant. Each 7th soldier was given a Korean "running mate" with whom he was supposed to "buddy" both in training and in combat.

While the 7th trained to a fine edge in Japan, the "police action" in Korea started to assume all the earmarks of an infantryman's shooting war. The U. S. Japan garrison was stripped bit by bit as divisions were rushed across the Sea of Japan in an effort to halt the North Koreans who were riding the crest of aggression behind a vanguard of Russian-made T-34 tanks. The Eighth Army was fighting with its back at the sea when General MacArthur decided on an amphibious invasion of Korea's west coast, designating the 1st Marine Division and the 7th Infantry Division to do the job.

Soon the 7th Division - code-named "Bayonet" for its movement to Korea - was to board troop transports. A day later the shoreline of Korea was ahead. The old-timers among the men grimaced knowingly long before the embattled peninsula became visible. As many of the GIs expressed it in the letters they wrote home. "You could sure smell Korea a long time before you saw it!"

The amphibious venture was a classic. It put U. S. forces on Korea's west coast while the active front was still on the Naktong perimeter far to the southeast. The landing at Inchon sent the North Koreans reeling, and soon the GI's and Leathernecks were moving in on the South Korean capital city, Seoul. The Division's 32nd Infantry boldly seized Angyang-ni and South Mountain, terrain features dominating Seoul. Then, with the capital in the bag, the Division turned its attention to the south. The 17th Infantry, yanked out of Eighth Army reserve, rejoined the Division in time to fight a fierce 12-hour battle for two vital hills southeast of Seoul. Soon Barr's soldiers were in command of all terrain south-southwest of the Han River; they continued to drive toward the southeast to seize key terrain, and also to cut off possible enemy escape routes. The Division then marched 25 miles east to Suwon to capture the important rail juncture of Ichon.

Suwon was taken by the 31st Infantry Regiment fighting under its battle flag for the first time since its surrender to the Japanese on Bataan. The 31st pushed below Suwon and after a stiff fight cleared a tank-supported enemy pocket near Osan, site of the Communist tank breakthrough against the 24th Division some sixty days earlier. Here the Division linked up with the flying column from the 1st Cavalry Division, which had raced 102 miles from the Naktong, through enemy-held country, to clear the way for the joining of the two U. S. forces. With the arrival of troops from the Naktong perimeter the mission of the Inchon landing force was complete, and the 7th started a long overland truck march to the east coast of Pusan. Here training was renewed, and harried troop commanders attempted to get replacements for their combat-thinned ranks.

Soon the Bayonet soldiers were again loading into troop transports. This time the target was the east coast village of Iwon. Their orders were: "Advance to the Yalu!"

The Yalu was the river boundary between North Korea and Manchuria. To its north was the "privileged sanctuary" which supplied the North Korean Army, and which was to play so significant a role in the ultimate fate of the Bayonet soldiers who came ashore at Iwon on the last day of October in 1950.

After an unopposed beachhead landing on the last day of October, 1950, the Division started driving north. Along the way they met a sharp skirmish at Pungsan and a harsh firefight at Kapsan. The push continued in arctic-like cold weather, and on November 20, Colonel Herbert B. Powell's 17th Infantry slogged into Hyesanjin-on-the-Yalu--the first U. S. unit to reach the Manchurian border. Hyesaujin, which means "ghost city of broken bridges", was the northernmost point of advance by the United Nations' command in three years of bitter warfare.

"We swept through the city," related Colonel Powell, "and took a good look around. Then we dropped back to a good hill position to wait for something to happen." They didn't have long to wait.

The Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) intervened in the war on November 27, striking twin blows against Eighth Army in western Korea and X Corps in the east. The enemy attack caught the 7th strung out, with some elements as far as 250 miles apart. The 17th was northwest of the Chosin at Hyesanjin. Neither of the other regiments was intact at the time the action started, nor were they able to get together during the furious action that followed.

Captain Charles Peckham's Company B, 31st Infantry, had been on special detail, and was nearing Koto-ri en route north to rejoin its outfit, the 1st Battalion, which was supposed to reinforce the 3d Battalion on the northeast shore of the Chosin reservoir. The 2nd Battalion was at Majong-dong awaiting orders. Peckham didn't get through. At Koto-ri his Company was impressed into a hurriedly organized special column called Task Force Drysdale. Composed of Peckham's Company, a company of Marines, and the 41st Commando (Royal Marines), Task Force Drysdale fought its way up the main supply route to crash the Chinese road blocks and bring much-needed supplies and ammunition to the sorely-pressed defenders of Hagam-ri. They sustained heavy casualties en route.

Furthest north at this time was the 1st Battalion of the 32d Infantry under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Don Carlos Faith, Jr. Faith's command, beyond the northeast shore of the reservoir, engaged in five days of hellish combat. Fighting in the cruelest weather, surrounded, vastly outnumbered and outgunned, knowing full well that no help could come, they fought to the end.

Behind them was the task group headed by Colonel Allan D. MacLean, commander of the 31st Infantry Regiment. MacLean had with him his 3d Battalion, his heavy mortar company, the 57th Field Artillery battalion, and a few self-propelled automatic weapons. In the five days that followed, MacLean's battalion of the 31st suffered nearly as many casualties as the entire 31st had suffered on Bataan.

In one particularly vicious attack the Chinese drove a wedge between Faith's and MacLean's forces. MacLean was conferring with Faith at the time, and was thus cut off from his command. Furthermore, both outfits were completely surrounded. Knowing it was essential for them to link up again, MacLean and Faith decided to mount an attack to demolish the Chinese block between their outfits. In the firefight that followed, MacLean disappeared, never to be seen by his men again; much later they learned he had been taken prisoner.

Faith's soldiers reached MacLean's command just as the Chinese were getting set to launch an attack on the artillery batteries, hit the Communist soldiers from the rear, and drove them off, killing more than 6o of them. Then Faith combined the two U. S. forces, and decided to attack to the south in an effort to reach the base at Hagaru-ri.

His tattered frost-bitten soldiers were in miserable condition. Most of them were walking wounded; some were forced to use their weapons for crutches. Faith rallied the dispirited men and led them down the road toward the enemy strong point which threatened to wipe them out. He called the shots all the way as his men, near the point of collapse after five days of savage close quarters' fighting, followed him to the roadblock. Faith was in the lead, and was finally knocked down; but his men overran the enemy position and found themselves momentarily out of contact with the enemy.

Practically none of the officers or key noncoms were left. The remains of the task force dissolved into small groups for the last ten miles down to Hagaru-ri. It was only ten miles, but it might as well have been ten thousand for some of them. That night, December 1, the dazed and bloodied survivors started straggling in. When the last survivors of Task Force Faith reached the lines at Hagaru-ri on December 4, the 1st Battalion, 32d Infantry, which had started its march north on November 25 one thousand strong, was able to muster only 181 officers and men.

Nor was the ordeal over. In column with the Marines, the elements of the 7th Division which were in or around Koto ri had to fight their way south to the Hamhung perimeter in a blinding snowstorm with the enemy dogging at them all the way, sniping at them from the ridgelines, and getting closer with each passing hour.

Not all of the 7th Division had suffered the terrible toll inflicted on Faith's Battalion and MacLean's Task Force. A number of units redeployed to the Hungnam port area intact, still fit to fight. But the last days of 1950 were mostly sad ones for a Division which had once been known as the "Lucky Seventh." It had barreled up to the Yalu River, the only U. S. Division to achieve that high water mark, and then had been set upon by the massed divisions of a new enemy and forced to retrace its steps, fighting every inch of the way. Phase II of the Division's combat career in Korea ended with the bitter campaign of the Chosin Reservoir.

New Year's day, 1951, found the Division, spearheaded by the 17th Infantry Regiment, again heading north, attacking at Tangyang in South Korea, and blocking enemy threats from the northwest. Soon the entire refurbished Bayonet was back in action around Cheehon, Chungju, and Pyongchang. The 7th was under a new commander, Major General Claude Birkett Ferenbaugh. The Bayonet engaged in a series of successful "limited objective" attacks in the early weeks of February. Late February found the 17th Infantry Buffalos, now under the command of Colonel William Quinn, driving against a ridge near the village of Maltari. A platoon from Company E inched close to the crest only to be enveloped in automatic weapons fire from both flanks and the front. The leaders of both front-running squads went down, and the leaderless men were dazed and bewildered. Corporal, Einar H. Ingman, a 21-year-old soldier from Tomahawk, Wisconsin, quickly assumed command. He reorganized the squads under fire, and then waded into the enemy all by himself, taking out a machine gun crew with grenades and rifle fire. Another enemy gun 50 yards to his right opened up, and Ingman went after it. Halfway there he was hit by a grenade, but managed to keep going. He was almost to his target when the enemy gunner spotted him and fired a long burst that caught Ingman in the head and neck and sent him reeling to the ground. But the Wisconsin soldier rose to his feet and resolutely resumed his one-man war. He wiped out the machine gun crew, then slumped unconscious over the gun he had taken. The two squads followed him and got to the emplacement he had taken just in time to see a large number of the enemy fleeing down the far side of the hill, throwing away their rifles. Ingman, who had also been wounded in the fighting near Seoul, recovered from the wounds he got in this furious action, was promoted to Sergeant First Class, and awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

The Bayonet was put in the van of the IX Corps assault, and fought a fierce three-day battle culminating with the recapture of the terrain that had been lost near the Hwachon Reservoir just over the 38th Parallel in North Korea. Here the Division enjoyed a victory that was doubly sweet. In capturing the town bordering on the reservoir it cut off thousands of enemy troops who were trapped in the important electrical power center, and at the same time gained some measure of revenge for the bitter memories of the Chosin campaign. The IX Corps' attack, Operation Piledriver, continued in the face of fanatical Chinese resistance. The enemy waited for the GI’s in the hills beyond the Hwachon, entrenched in log bunkers and reinforced pillboxes behind heavily-mined roads, coming out to fight at night.

The end of June brought the 7th a welcome assignment to the rear, the first relief from frontline duty since the Division had reached Korea. There was the inevitable reshuffling of assignments. Colonel Quinn was ordered to a new assignment; His successor was Lieutenant Colonel Hal Dale McCown. Lieutenant Colonel Glen A. Nelson, who had been a battalion commander under Mickey Finn back in the Hourglass days of World War II, took over the 31st Infantry Regiment; and Colonel Charles McNamara Mount, Jr., took over the 32nd Infantry.

After a brief rest the Division was ordered into defensive positions north of Hwachon. Toward the end of August, a number of limited objective attacks were ordered to take key terrain features and improve the front lines. In ten days the Division captured five important hills, in what one division historian has described as "the best fighting in tire Division's history".

When the Division returned to the lines after another assignment in reserve, it was to the Heartbreak Ridge sector recently vacated by the 2d Division. The 7th also took in the northern the of the "Punchbowl." About this time General Ferenbaugh left, to be replaced by Major General Lyman L. Lemnitzcr, under whom the Bayonet continued to defend "Line Missouri" through September 1952. By that time General Lemnitzer had been replaced by Major General Wayne C. Smith, who took over while the Division was still on the so-called "Static Line".

The Division's Operation Showdown was launched in the early morning hours of October 14, 1952, with the 31st Infantry Polar Bears passing swiftly through the lines of the 32 Infantry Buccaneers. The target of the assault was the Triangle Hill complex northeast of Kumhwa. The 31st moved against a strategic spot which for obvious reasons was named "Jane Russell Hill".

The next day the Bayonet attacked again. And again on the day after that. Three days later the attack finally succeeded. In one of the counterattacks mounted by the Communists, a strategic Bayonet position on the hill would have been overrun but for the courage of PFC Ralph E. Pomeroy, who calmly pulled his machine gun off its tripod and started walking downhill toward the enemy, firing into them as he walked, hand grenades blew the helmet off his head, but he continued into the enemy's midst. And when he came to the end of the ammunition belt, he swung the machine gun as a club, continuing to close with the enemy until they engulfed him by sheer numbers. He was still fighting them when his buddies of Company E, 31st Infantry, got their last glimpse of him.

The Bayonet remained in the Triangle Hill area until the end of October, when it was relieved by the 25th Infantry Division. It had won an important victory in what Lieutenant General Reuben E. Jenkins, commander of IX Corps, termed "the most violent action of this corps in over a year." General Jenkins also said, "In my opinion there could be no finer assignment for a Corps Commander than to command a corps composed of divisions of the quality of the 7th Infantry Division".

The New Year (1953) found the 31st Polar Bears and the 32nd Buccaneers holding positions on "Line Jamestown" awaiting the return of the 17th from Koje-do. The Buffalos rejoined the Division in mid-January, to join in the patrol activity around Old Baldy and Pork Chop. April brought a stepping-up of the enemy's ground activity and Operation Little Switch, the exchange of sick and wounded prisoners. The Communists overran Pork Chop, but the 7th counterattacked and re-won the OP the next day. While the, negotiations continued their deliberations at Panmunjom, the frontline activity continued. July 6 the Reds launched a determined attack against Pork Chop--the strongest display of force the Bayonet had seen in that sector. Five days of savage, fighting followed with the same ground being taken and retaken as the tide of battle surged first one way and then the other.

At twenty minutes before eleven AM. on July 27, 1953, a message was received by the Division--and immediately flashed to all units--that an Armistice had been signed and was to go into effect at ten that night. Collectively and individually the Division breathed a sigh of relief, and each man prayed silently that, having got this close, his luck would hold out another twelve hours.

On OP Westview, where a ninety-minute battle had raged the night before, the Bayonet soldiers wondered anxiously if the enemy might decide to finish the war in a blaze of glory. Those were 12 extra-long hours.

The men checked and rechecked their gear, and cleaned their weapons. At one outpost six rounds of mortar fire fell inside the perimeter during the afternoon, but none of the boys were hit. Around nine PM the 7th soldiers noticed that the Reds had a huge searchlight beam playing on Old Baldy.

Forty-five minutes ticked slowly by. The latest order was passed from man to man: "No firing from now on--it's up to them!"

Then the hour struck; the campaign in Korea had come to an end.

Someone said, "Look. They shut off that damned searchlight." A 7th Division soldier wrote in his diary, "We could hear voices across the line, but for the first time the angry noises of warfare had disappeared".

Forty-eight months after the cease fire the 7th Division was still on duty within shouting distance of the battlefields of 1950-53. But the men who wore the Hourglass-shaped shoulder patch of the Bayonet Division refused to be annoyed when, as often happens, some humorist points to their insignia and says, "Why, there goes the Korean National Guard".

31st Infantry Regiment in Korea

In January 1946, General MacArthur restored his former guard of honor to active service at Seoul, Korea, assigning the 31st to the 7th Infantry Division. For the next 2 years the 31st Infantry performed occupation duty in central Korea, facing the Soviet Army across the 38th Parallel. In 1948, the occupation of Korea ended and the regiment moved to the Japanese island of Hokkaido, occupying the land of its former tormentor. When North Korean troops invaded South Korea in the summer of 1950, the 31st Infantry was stripped to cadre strength to reinforce other units being sent to Korea. In September, the division was restored to full strength with replacements from the U.S. and Koreans hastily drafted by their government and shipped to Japan for a few weeks training before returning to their homeland as members of American units. The 31st Infantry returned to Korea as part of MacArthur’s Inchon invasion force.

In November 1950, the 31st Infantry made its second amphibious invasion of the campaign, landing at Iwon, not far from Vladivostok where the 31st had fought just 30 years before. With North Korean resistance shattered, UN troops pushed toward the Yalu River. When Chinese troops swept down from Manchuria, they surrounded a task force led by the 31st Infantry’s commander, COL Alan MacLean. COL MacLean and his successor, LTC Don C. Faith, were both killed during the ensuing battle. LTC Faith won the Medal of Honor for his gallant attempt to lead the command to safety. Only 385 of the task force’s original 3200 members survived.

The 31st Infantry was far from finished. The regiment was evacuated from North Korea by sea to Pusan. There it rebuilt, retrained, and refitted and was soon back in combat, stopping the Chinese at Chechon, South Korea and participating in the counteroffensive to retake central Korea. Near the Hwachon Reservoir, two members of the regiment earned the Medal of Honor in some of the war’s most determined offensive combat. By the summer of 1951, the line stabilized near the war’s start point along the 38th Parallel. For the next two years, a seemingly endless series of blows were exchanged across central Korea’s cold, desolate hills. Names like Old Baldy, Pork Chop Hill, Triangle Hill, and OP Dale are among the war’s most famous battles, all fought by the 31st Infantry and bought with its blood. By the war’s end, the 31st Infantry had suffered many times its strength in losses and 5 of its members had earned the Medal of Honor.

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | back to top |

|

| Contact | What's New | About Us | Korean War Topics | Support | Links | Memoirs | Buddy Search | |

|

|

© 2002-2012 Korean War Educator. All rights reserved. Unauthorized use of material is prohibited. |

|

|

- Contact Webmaster with

questions or comments related to web site layout. |

|