|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||

James Henry ChristiansenRockledge, FL- "I perceived Korea to be the arm-pit of the universe, and not worth two cents, but when you saw the misery of the people, you had to care, no matter how rough or tough you thought you were." - James Henry Christiansen

|

|||||||||||||||

Memoir Contents:Pre-MilitaryMy name is James Henry Christiansen, and I was born October 13, 1930, in Atlanta, Georgia, a son of Christie William Christiansen Sr. and Ollie Stallings Beall Christiansen. There were two other children in the family: Vivian Christine Christiansen Hall (born 1925 and still living) and Christie William Christiansen Jr. (born 1927 and now deceased). Father was a soldier during World War I and World War II, although not continuous service. He was in each war three years. At other times he was a furniture salesman or store manager. Mother did secretarial work for Burkhart Shier Chemical Company in Knoxville, Tennessee, and American District Telegraph Company in Atlanta. I attended Park City Lowry grade school in Knoxville, Technological High School in Atlanta, and Brown High School in Atlanta. I did not graduate. I quit school on my 18th birthday and joined the Army the following day. While I was in school, I worked several odd jobs. I was a shoeshine boy at Ft. Oglethorpe, Georgia, where I mostly shined the shoes of WACs. I also was a paperboy, delivering papers for the Atlanta Journal. I worked as an usher at Roxy Theater in Atlanta, too. I delivered and installed typewriter ribbons for Kee-Lox Manufacturing Company in Atlanta; was a "50% up and 50% down" elevator operator in the Atlanta National Building; and was a radio repairman for the Carroll Furniture Company. During World War II, my father served in the U.S. Army; my brother was in the U.S. Navy Seabees; and my brother-in-law, Walter Dewey Hall, was in the U.S. Army. I was attending school during that time. I participated in tin can drives, paper drives, and copper drives. I more or less participated as an individual and not with groups.

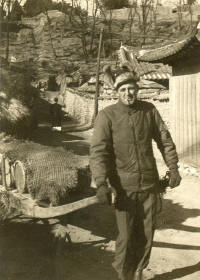

I was scheduled to graduate in June of 1949, but I knew there was no money for college, and with my record, there would be no scholarship. The best future I could look for was a meaningless job. I had made the tragic mistake of falling in love with a beautiful girl, and knew that if I stayed in Atlanta there was absolutely no chance of my getting her. If I went away and made something of myself, I had maybe one in a million chances to get her. My best friend, Donald W. Webb, joined with me. He wanted to join the Navy, but I couldn't swim. I quickly and successfully argued for the Army. Less than two years later, on 10 September 1950, he was killed in action. My long shot did not come in. I had lost my best friend, and at about the same time he was getting killed, my girlfriend was getting knocked-up. Donald Ward Webb joined the Army looking for adventure. So did Thomas Jerome Howard and Bobby Matthews, who also joined the US Army at the same time Donald and I did. My father had ordered me not to join. When I disobeyed him, he disowned me, but later relented. I joined on 14 October 1948, leaving from home via the Southern Railway for Fort Jackson, South Carolina. Matthews and Webb traveled with me. Howard was held back for a spell for further eye checks. Nothing significant happened along the way. There were about forty of us and I, at 6'1" and 145 pounds, was the heaviest among us. There were precious few fat people in 1948. Basic TrainingWhen we got to the camp, we were given sheets, blankets, and pillowcases, and herded into an old barracks with the warning, "No gambling. Absolutely no gambling. We will tolerate no gambling." This was an old con that I recognized from my father’s company in Ft. Oglethorpe (he was first sergeant). The idea was to make sure that you did gamble, and then the instructor would swoop in and confiscate all the money, which was never seen again. So we started a game of poker and I was dealing when someone yelled, "Here comes Cobb." I told them everybody to put their money in their pockets, and I kept on dealing. Cobb very righteously yelled, "Aha. Caught you gambling." I answered that we weren’t gambling, but merely playing a game of rummy. He was mad because he had a date that night and no money. So he said for me to follow him. We went halfway down the stairwell and he asked, "Do you want to lend me five for eight?" I said for him to put it on paper. He said, "Write it and I’ll sign it." So on my very first night, I had made three bucks, gained a little respect from my fellow recruits, and had PFC Robert E. Lee Cobb, also of Atlanta, Georgia (and with a name like that, where else?), wrapped around my little finger. Cobb was later reported as KIA in Korea, but he was not. I ran into him in Atlanta in 1952. We got drunk and he wrecked his car. Basic training was eight weeks. We took physical training (a lot of it), did dry rifle fire and then hot fire on the range, and participated in first aid training. We were taught how to make beds, learned military courtesy, and read the Articles of War. We also drilled. Some called this dismounted drill and some called it close order drill. We called it, "Disorderly drill." Our days were regimented with wake up, reveille, personal hygiene, cleaning the barracks, chow, first call, training, chow, second call, training, chow, free time, and bed. I quickly developed something I called "mess hall discipline." I had always been a finicky eater, but I learned to eat everything they put on my tray. To this day, if I happen to be in a mess hall, I’ll eat things I wouldn’t otherwise eat. The food was nourishing and well-cooked. Ours was a company-sized mess as opposed to a consolidated mess. We got to know the cooks because they slept in the same barracks with us. Once when I had been to the dentist and had a wisdom tooth CHISELED out and returned to the company area, I saw one of the cooks and asked him what was for chow. It was steak. I asked if it was tough and he said, "Yes." I told him of my jaw and he said, "See me when you come through the line." He had soft-boiled eggs and banana pudding for me. On Thanksgiving night 1948, that same cook, Corporal Epperson, came into the barracks and asked if any of us would volunteer to come help the KPs, because the big meal had overwhelmed the system. About ten of us did, and he fed us all again. Sometimes S/Sgt Smith woke us up in the middle of the night. When he did this, he was generally pissed about something. But our instructors were not strict at all. If we halfway tried, they could be pretty lenient. I had PFC Cobb in my hip pocket, and S/Sgt Smith treated me kindly when I managed to catch pneumonia during bivouac. He put me on the sick book and sent me to the hospital. The instructors were firm, but not unyielding. If they ever used corporal punishment, I never witnessed it. I have fond memories of my instructors. We were not at war at the time I took basics, and life was not hard for me during the training. We had to fall out in the middle of the night a couple of times, but that was minor. Many of the recruits lacked self-discipline, so the Army had to supply all of the discipline. I looked on it as a game. If it ever got real rough, I said to myself that millions of others had made it through, and by God, so could I. Collective-type discipline was a very effective tool if used right. It united all of the platoon against the offender, and they usually straightened him out. (I used it myself, as I will explain later in my memoir.) I think that only one guy in our platoon didn’t make it through basic training. He was a "mad Russian" from New York named Peppin. He was disruptive in formations and training. Once at roll call, he answered his name by farting. Needless to say, he didn’t make it through. I do remember when a recruit from Seneca, South Carolina named Claude Rothell, dropped his M-1 rifle. S/Sgt Smith made him do 25 pushups with the rifle clutched in his teeth. When he had completed the pushups, Smith told him to fall back into the formation. The recruit (who was no small boy) got up and went back to the formation with the rifle still clamped firmly in his teeth. S/Sgt Smith had not told him to remove it, and he held it until he was told. Smith liked that. I also remember when a recruit we called "Preacher" made the mistake of sitting on one of the cook pots while he was on KP. The cooks gave him holy hell the remainder of the day and far into the night. The only thing I got in trouble for was "bouncing" when I marched. I have a peculiar gait that causes me to "bounce" while marching, and I was yelled at continually about it. Church was offered during basic training. There was a chapel near the training area that conducted services for all faiths, and we were given time to go. Very few of us did, with only "Preacher" going from our platoon. The instructors (cadre as we called them) didn’t interfere. Many of the guys went into Columbia to go to church. You could pick up girls there. Fort Jackson was located in piney woods that were replete with chiggers (little red bugs). When you were out in the woods, they invariably found their way to the softest flesh on a man’s body, i.e., his penis and testicles. There they burrowed into the flesh. You killed them by painting the resulting welt with fingernail polish that burned like a branding iron, but killed the chigger. They were pretty dormant during the fall and winter. We had to qualify with the rifle, pass a physical training test, and stuff like that, but nothing special. We also had to watch the usual training films. "The Late Company 'B'" was a film about maintenance. There was also a spate of VD films. I remember one in particular. This soldier went into a bar and sat down. At the other end of the bar was a woman—a real dog—who was so ugly she would turn you into stone like Medusa. After his first drink, he looked again and, while still ugly, she wasn’t so ugly. After each succeeding drink, she got prettier until he was quite drunk and she was very beautiful. He woke up with a dose of clap the next morning. I really never regretted joining the Army while I was in basics. It was a far better life than the one I had in Atlanta. We were very poor. I had ran away from home twice before I joined the Army. I did, however, desperately miss my girlfriend (the one who later got knocked up by some other man). I always appreciated my instructors, and when I eventually became an instructor in the Far East Signal School, I learned first hand what they go through. When basic was completed, there was the obligatory parade. (There was a parade every Saturday for the graduating class honoring somebody.) Our honoree was some damn cook who was retiring after 20 years of exemplary service. I didn’t think that I was qualified for combat after finishing basic training. I thought the training should have been more comprehensive. I knew how to do a lot of things that I didn’t before, but I didn’t think any of them would save my life except maybe the rifle training and the physical training. But I really didn’t think about it at all. We were not at war and combat was the farthest thing from my mind. I was in better physical and mental condition and my morale was better. I had achieved some very small bit of self-respect, of which I had none before. Radio SchoolDonny Webb and I went directly to Camp (now Fort) Gordon, Georgia, after basic training was over. We took the bus, and when we got off of it, it was a blazing hot day in December. We wondered what July would be like. We were taken into an old building and the Cadre, who were all ex-paratroopers, made us do pushups just to say hello. They then turned on a loudspeaker and played a message in Morse code at 25 words per minute. They said we would all be able to read that before we left. It scared hell out of us. The paratroopers herded us around, but they did not teach us Morse code. For your information, every "stick" of paratroopers (all of the paratroopers on a particular plane who jump together) had within it a Morse radio operator. He was the unlucky one. He had to jump with the radio strapped to him in addition to all of his other gear. There being no miniature radios in those days, he often had to be lifted up into the plane by his buddies because he was too heavy to do it himself. Not long after we arrived at Camp Gordon, we went on a ten-day Christmas leave. That Christmas Eve of 1948 was the happiest I ever had. My girlfriend visited our house and wowed everybody. Sometimes I wore the uniform and sometimes I wore civvies. I don’t remember any particular comments about my being in the Army. I don’t think anybody gave a damn. When leave was over, I rode the Greyhound Bus back to Camp Gordon. Soon after, Thomas Howard caught up with us. Since it was only 150 miles from Atlanta and we had each weekend off, the three of us hitchhiked home many times in the weeks to come. We also could go off post each night if we wanted. At Camp Gordon, we learned radio procedure and radio equipment of the era, but mostly Morse code. I can only remember the instructors named Hofslund, Youngblood, and Schuhmacher. Schuhmacher was my sending instructor and now lives about a mile and a half from me here in Rockledge. We have both been Commander of the same Legion Post 22 in Cocoa. We were started out on "Z" speeds. Z1 was a group of seemingly unrelated letters sent at 5WPM. They included the letters Y, H, N, U, J, M, T, G, B, R, F, and V. When you passed that, you went to Z2, which contained all of the Z1 letters, plus I, K, E, D, and C. Z3 contained all of those letters, plus O, L, W, S, and X. Z4 contained all of those, plus P, Q, A, and Z. Z5 was the numerals. When we had completed Z5, we had qualified at 5WPM. This was all done on paper using a pencil. Then they upped the ante; you went to 7WPM, then 10, 13, 16, and 18. The highest we had to do with pencil was 18. In the code room, we were sent letters of the alphabet in international Morse code. This sending was done by a recorder, not a human being. We had two five-minute tests every hour, with the machine sending to us. We had to correctly translate from code to English any three consecutive minutes without error to pass that speed and go on to the next. We sat at study carrels, wearing headsets, with each headset individual controllable. Thus we could work self-pace. We had to write or type what was sent to us on paper. We were then yanked out of the code room and sent to the typing room to learn to type. Our typewriters were called "Mills", although I don’t know why. There were no lower case letters—only caps, and there being no lower case L, it also had the numeral 1 on it as does a computer keyboard. We only had a week to master the typewriter, but that was enough. Then we were sent back to the code room where, instead of using a pencil, we used a typewriter. We were put all the way back to Z1. Lo and behold, those Yankees were damn clever. Z1 turned out to be the letters on the typewriter that were struck with the two index fingers. Z2 included the major fingers. Z3 the ring fingers and Z4 the pinkies. The numerals, of course, used all eight fingers. There was a method to their madness that took a while to fathom. In the beginning of our training, the Z groups seemed unrelated and we couldn’t figure out the logic of the particular combinations. We thought they would teach us A to Z. They didn’t. By their method, when you had finished Z4, you had the whole alphabet. Then we had to go through the whole process again: 7, 10, 13, 16, 18, but we didn’t stop there. We went on to 20, 22, and 25, all on the typewriter. Somewhere along the line we had been given a sending orientation. They taught us how to adjust a telegraph key, properly place our fingers on it, and how to press it down without bounce, which caused static. They then let us play with it for a while, all the time monitoring us individually and offering on the spot corrections if we were doing it wrong. Most of us had problems here, but we eventually mastered it. In Korea, I could send better than I could receive. Each operator, unlike the machine that taught us code, developed a peculiar style of sending. This was called his "fist." An experienced operator can listen to someone sending and know exactly who it is. His fist is just like his signature. We had to pass the same speeds sending up to 20WPM. They tested us by making us send to a tape recorder, and then copy it back. They figured that if we couldn’t copy our own mess, then no one else could. It was an amazingly good way to teach code. (In 1951, I became an instructor at the Far East Signal School and used the exact same scheme with good results.) We had to pass 18 pencil, 25 typewriter, and 20 sending. We had to pass written exams on procedure, and demonstrate proficiency on the various radios. Radio procedure is a language developed to facilitate the passage of messages between two or more operators. Voice radio has its own procedure; Morse has a different one. Teletype has one that nearly duplicates Morse. Here are a few examples:

Procedure is a very complex subject, and very difficult to learn, but once you have it, you pretty much have it for life. And speaking of procedure, we (the many radio operators in Korea) developed a new procedure that has been adopted by the Armed Forces. It is called "break in." In the example above, when the receiving operator first noticed he had made a mistake (i.e, missed the word after Company) he right then pressed down his key. The sending operator heard this signal between the dots and dashes he was sending, and immediately stopped sending. When the receiving operator senses that sending had stopped, he then sent "Company." The sending operator then resent the word Company and all that followed it. There were no call signs or other garbage involved. This was developed out of necessity. We simply didn’t have time for all of the proper stuff. Primarily, we were taught to use the SCR-399 radio. It was a huge monstrosity on the back of a 2 ½ ton truck, pulling a 10KW generator (the PE-95) behind it on a ton and a half trailer. This is what we used in Korea. There were various other smaller radios whose nomenclature I don’t remember. At the end of our training, we had a week long field exercise where it all came together. We set up stations in various parts of the piney woods surrounding Camp Gordon, and sent messages to one another, all the while being monitored by the ever-watching instructors. The instructors took this extremely seriously, although the word combat was never used. We were at peace and it just didn’t enter anybody’s mind. We knew that we were training under field conditions (which literally translated meant combat conditions), but none of us were thinking war or combat. I knew that if called upon, I could operate that radio under damn near any conditions. Ultimately, I was called upon to do just that. There was really no schedule to complete radio school. It was all self-paced, so some graduated before others. We had 7-hour days, 5 days a week in the classrooms. For me, it was six months. We started in January and I cleared post on 5 July 1949. For Don Webb, it was 11 weeks longer. He got stuck on 22WPM and it took him all that time to pass it. In retrospect, that probably cost him his life. If he had graduated with me, he probably would have gotten the same duty station I got in Japan, and would have been with me. I survived. Opportunist OnboardAfter I finished my radio school training, I was assigned to the Far East Command in Japan. I didn’t particularly want to go, but I had signed on the dotted line. I knew I would be there two or three years, and the thought of leaving my girlfriend (the one who eventually "done me wrong") hurt. I can’t explain that any clearer. It physically hurt to be away from her. There was nothing notable or memorable about my departure. I probably shook Dad’s hand, kissed Mom and my girlfriend, and got on the train. I was to leave the country from Seattle, Washington, but I was held up there for a while because some of my records were missing. In late August of 1949, I boarded the USNS General Shanks for the trip to Yokohama. I don’t know anything about the person the ship was named after. It was a transport ship, but not necessarily a troop transport. We lived in the bowels of the ship, but it had staterooms for the dependents. It was ran by merchant seamen, not Navy. They were mostly Filipinos and Neseis. I didn’t see any other services, and I don’t know of any cargo other than luggage. This was my first trip on a big ship, but I did not get sick. I woke up the first morning out and the ship was gently rocking back and forth, like I was a baby in a crib. I thought that this was not sickening—it was pleasant. Right at that moment I knew I wasn’t going to be sick. Others were though. They puked everywhere; in the toilets, in the urinals where you then had to watch the vomit run back and forth from one end to the other if you used it. They puked in the mess hall and would come walking out with a stupid smile on their face and their cupped hands full of vomit. Ultimately, they puked over the side where it blew back up into the faces of all who were downwind. But for some reason, I never got sick. I had been sick once on a charter fishing boat during World War II when I was visiting my father who was then stationed on Miami Beach. Tough war. If we hit any rough weather, it must have been in the middle of the night when I was sacked out. It took about 10 or 12 days, I think, to get to Japan. It turned out to be a pleasant voyage for me, although I did nothing for entertainment. The troops were herded out on the deck each day and they had to stay there. We weren’t allowed to stay below on our bunks. I, however, missed that particular joy each day. In the Army there is an axiom – "Don’t volunteer for anything." But I had already found that that axiom had to be tempered with a little common sense and intuition. I had learned that in basics when Epperson wanted us to come help clean up the mess hall. I reinforced it in Seattle when the First Sergeant came in and wanted somebody who could type to volunteer for a few minutes work. I did and worked myself into a plush assignment. The same thing happened on the ship. A Sergeant came in and wanted somebody who could type. I did, and from that moment on I was the "Reporter" for the ship’s newspaper. I had to wear a class B uniform, but I had free run of the ship, including the staterooms where the dependents stayed. My sole duty was to sit in the dependent’s lounge (bar) each day and record the winners of the daily bingo games. I then typed this up in a usable format and turned it over to the Sergeant. I was then free to do what I wanted, including going back to the lounge and drinking coffee, or skulking around the dependent’s quarters looking at pretty women. It beat hell out of standing on deck having vomit blown on you. You may notice that all of my years on the streets of Atlanta had made an opportunist out of me. I had become quite a hoodlum in my youth. It had seemed like an option to me from the crappy life I had, but it didn’t solve anything—just added to the problem. I roamed the streets "rifling" (burglarizing) cars and stealing whatever I could. I had been expelled from Tech High three straight semesters—a year and a half of high school and not a credit earned. The summer when I was 15 (1946), I knew I was headed to the Georgia State Reform School on the day after Labor Day. Georgia law dictated that I must be in school until I was 16, but the Superintendent of School, a purple-haired lady named Mrs. Ira J. Mann, wouldn’t allow any school to enroll me. I was that bad and she hated me. I had few choices. I could leave Georgia and go live with my sister in Knoxville, but I didn’t like that idea. I thought that 15 was a little young to begin running from the law, so I bided my time. That summer, I read in the paper that Mrs. Mann had retired and there was a new Superintendent named Mr. Edwards. I thought, what the hell, it’s worth a try. I went to the School Board on the 10th floor of the City Hall and asked to see Mr. Edwards. The lady tried to brush me off. I persisted and told her I would come back anytime he was available, but I had to see him and nobody else. Finally they relented and told me to come back at 3:00 p.m. on Tuesday. Before I left I told her that somewhere in that building was a big, fat file with my name on it, and requested that Mr. Edwards read it before my return. When I returned, I knew that he had done so because his attitude was extremely hostile. I asked him if he had read it and he replied that he had. I then said that everything in there was true. There were no exaggerations, no false statements or insinuations, that I confessed I was guilty and everything in that file was true. This took him aback some; he had clearly thought I would deny the file. He asked what I wanted and I said that I wanted to go back to school. I told him that if he would let me, I promised him man to man that I would never do anything like that again and I would bring him an all A report card every semester. He let me go back to school. I kept my word to him. From that day on I never even spit on the sidewalk or jaywalked again. School was easy. There seemed to be nothing a schoolteacher liked better than a bad boy gone good. I had to report to Mr. Edwards every Tuesday for over a semester. Then one day I came in for my regular appointment and was told to wait. Three and a half hours later, I lost my temper and got up and went home. Then I immediately regretted it. I thought to myself, "You damn fool. You’ve blown it." So I went back on Wednesday to ask for another appointment. He came out smiling and said, "Congratulations, Jim." He had set that up to see if I would come back or if he had to send for me. I was off probation and a regular student again. I still remember that man as the one who helped me turn my life around. As to the other stuff, that had all stopped a couple of years before. I had spent 10 days in the juvenile jail, and six days in the Indianola, Mississippi jail where I had been caught running away from home. Jail is not a nice place and I didn’t ever want to go there again. I realize that I have digressed somewhat from the subject at hand--my military service in the Korean War--but the above set of circumstances followed me all the days of my life, including the coming months that I would spend in the Far East Command, as I will explain in the pages ahead. In the meantime, I knew nary a soul on the ship. I was then, pretty much as I was all of my young years, a loner. The ship made no stops en route to Japan. It made the northern journey and we were in sight of Alaska. I wondered why anybody in their right mind would live there. Nothing "eventful" happened on the trip to Japan except that one of the dependent wives made a play for me. As much as I wanted to, I didn't. I was too scared. If they caught me, they would have castrated me and thrown me overboard. The following year, a couple of months before the Korean War started, I ran into her in Yokohama. But the situation was entirely changed and she wanted nothing to do with me. She turned out to be an MP Sergeant's wife. Thank God I was discrete. Duty in JapanOnce the ship arrived in Japan, I was assigned to "A" Company, 304th Signal Battalion. It was located right in the middle of Yokohama, where we lived in Quonset huts. Since they didn't need any radio operators at the time, I was given duty in the Eighth Army Communications Center in the carrier section. (Carrier is a telephone process where you put many simultaneous calls on one wire.) They then sent me to school to be trained in it. Years later, this would get me promoted to SFC. I had once again, in my sublime stupidity, stumbled into a good deal. I worked 28 hours a week. Because I worked in the Comm Center in Yokohama, I was supposed to have security clearance, but I didn't get it. My "hoodlum years" in Atlanta were starting to catch up with me. My Company's duty in Japan was operating the Communications Center. That was all we did. "B" Company did all of the field exercises. When I wasn't on duty, I stayed on the post most of the time playing table tennis and pool. Occasionally, I felt the call of nature and went into town to rent one of the women. I didn't like to do that, though. I had seen too many VD films. I also had the opportunity to see some areas in Japan where the aftermath of world War II was still evident. There were many bombed out buildings in Yokohama, and in 1951 I went to Hiroshima. There wasn't much to see though. I was so desperate to see my girlfriend that I applied to go to Officers Candidate School, figuring that if I got that, I would be in Kansas. Kansas was a lot closer to Georgia than Japan. The application was approved and sent back to me for one more document. By then the war had started and Don Webb was already being shot at. I thought that maybe if I was a Lieutenant perhaps I could marry my girlfriend, but I couldn't allow Don to go to Korea and me to go back to the states. I threw the application in the waste basket. My girlfriend continued to write to me--right up until the time she got knocked up. I still refuse to dignify it by saying "pregnant." I was in Japan from late August or early September of 1949 until the start of the war. I knew very little about Korea at the time, as did anyone else. At Camp Gordon, the Company Commander had given us a one-hour lecture on it and about the political problems there. That was in June of 1949, a whole year before the war started. The Army knew something. When hostilities broke out in Korea, I followed the news about what was happening there. It was obvious that we were getting our butt kicked. The Stars and Stripes carried a daily situation map, and I was afraid they were going to rename Pusan to Dunkirk. In Japan, I thought I had it made. I was working in the com Center as a carrier tech again, and was frozen to my job--I thought. I figured that I would sit this one out, but that didn't happen. The Battalion had already gone to Korea and left us Com Center guys behind. Then the Battalion Commander called back to Japan and gave orders to go through everybody's file and send him everybody in the Battalion who was a radio operator, regardless of what they were doing. I didn't want to go, but guess what. I thought that we were going to get our ass kicked. We were totally unready. I thought that if I was an example of the average soldier over there, then we were in deep yoghurt. I was pretty intelligent, but I wasn't a warrior. We had to pack all of our signal gear and get it on the boats. Signal gear was all of the electronic equipment that we used to supply communications: carrier bays, radios, telephone switchboards, power units to create electricity in the field, etc. They took those who weren't qualified on the rifle to the rifle range and gave them a refresher course. That did not include me. I was qualified as an expert with the M-1 rifle and the carbine (a small rifle). One qualified by firing at a target from varying distances up to 500 yards. You could qualify as a marksman (lowest rating), sharpshooter, or expert. Others scored your hits on the target and you were rated accordingly. They closed our EM club and gave away every drop of the stock to us troops. Then they were gone. I was told that there was a lack of soap in Korea and to bring plenty of soap. Hell, I found out that there was plenty of soap there. The rats ate my soap. I never knew rats liked Ivory Soap until then. That sounds stupid, but it's true. Sometime in early August of 1950 I left Japan for Korea. It was on a Saturday morning. I was told to get my gear together, for I was leaving that night. Saturday night I was put on a Japanese train for Sasebo. I had a lower berth in a sleeping car. Can you imagine that? Sunday I was in Sasebo getting shots, making out a last will, and allotting all of my pay to a bank in Atlanta. I met a kid from Brown High in Atlanta. I don't remember his name, but he had already been in Korea, been wounded, hospitalized, and was returning to the line. I don't know if he made it. Probably not. That evening I got on a Japanese ship where the ever vigilant American Red Cross gave each of us ONE cigarette. Those cheap bastards. It sort of reminded me of the last cigarette before the firing squad shot you. I never once saw the Red Cross in Korea. The next morning (Monday), I was in Pusan, and that afternoon I was in Taegu with my unit. Gone to HellMy first impression of Korea was that I had died and gone to hell. The ship arrived at Pusan Harbor in the morning, and we immediately disembarked. The port was very busy. There were Koreans unloading cargo at the port. I could tell upon arriving that I was either in a war zone or in hell. I didn't know which. I was already assigned to a unit. In Japan, I had been in Wire Company, 304th Signal Operations Battalion. While I had been away at Eta Jima, the Battalion had been reorganized. There were no more A and B Companies. when Colonel Galusha, the Battalion CO, called back for every radio operator, I was transferred from Wire to Radio Company. When I arrived in Korea, I was in Radio Company, 304th Signal Operations Battalion Forward. Our next highest echelon was 8th Army Headquarters. We were not in any regiment or division. I didn't know anybody in Radio Company, having just been transferred into it, but I knew most of the guys in Wire company who I visited regularly. I can't recall exactly who was there, however. We were transported from Pusan to Taegu by narrow gauge railroad ran by Koreans. My unit was located in an apparently old Korean (or maybe Japanese from World War II) army camp near Taegu. I base that statement on the fact that there were some old Quonset huts there. The unit was doing what it was supposed to be doing--supply communications for the 8th Army and all of its units. The 8th Army was the top echelon of command in Korea. It had to communicate with General Headquarters, General of the armies Douglas MacArthur in Japan. It had to communicate with its subordinate units (24th Division, 25th Division, 1st Cavalry Division, 2nd Division, 7th Division, 1st Marine Division, etc., and also the Corps Commanders and the Navy and Air Force--i.e., everybody) under it. We had to supply the means of communication. we used high powered radios, wire, carrier, and VHF to accomplish this mission. Ballistic FatherMy parents did not learn that I was in Korea until after it was an accomplished fact. And I'm not sure they cared. We were not especially close. I loved them because they were my parents, but I didn't like them. They were both weak moraled people. Their crimes against me were more crimes of omission rather than crimes of commission. With a little supervision from them, perhaps things would have been different. I couldn't stay in the same room with my mother for five minutes without getting into a yelling match. Dad cared about us, but he cared about women, whiskey, and gambling more. My father got into a shooting match with the Jehovah's Witnesses via the Atlanta Journal's Letters to the Editors. They won't serve in the armed forces during wartime. Dad believed that they were not a religion, but a "cowardly reason for not serving the country that has allowed them to become such a cult." He was very vociferous about it. When he found out I was in a war zone and one of them was working there in the same building with him, he went ballistic. The big boss, Mr. Craig Topple, went on a vacation and left Dad in charge. Topple wasn't out of the door for five minutes when Dad fired her. New to KoreaMy first duty in Korea was guard duty. Some Sergeant saw me standing around and put me on perimeter guard for the night. I was scared all the way down to my toenails. I had already heard all of the horror stories about how the North Koreans would slip up behind you and slit your threat, and everybody else on that perimeter had, too. They were shooting at anything that moved: a tree branch blowing in the breeze, the shadow the moon cast when it went behind a cloud, toad frogs, and the ever present rats. I was the only one who didn't fire my weapon that night. If there was one thing I was afraid of more than a North Korean slitting my throat, it was showing everybody else how yellow I was. That's stupid, isn't it? The next night, I was made ammunition bearer for Cpl Sy Redding on a .30 caliber machinegun, presumably because I hadn't fired my weapon that first night. He must have thought that exhibited some coolness under fire, but actually I was too afraid to show that I was afraid. I think Sy was from Wire Company. We were all from the 304th, which was attached directly to the 8th Army Headquarters. He transferred to the 25th Infantry a couple of days later and I was made gunner. Sy wanted to transfer out because he had been in one of the infantry divisions and had buddies on the line who he wanted to be with. The feeling of brotherhood runs strong in the military. I sure hope he survived. He was one hell of a good soldier. For one soldier to refer to another as a good soldier is high praise. I don't know what a "hero" is; I only know it ain't me. The only one I can even think of who might fit that category is Sy Redding, because he put himself in harm's way when he didn't have to do so. Somebody else then became my bearer when I became the gunner. I had never fired the machinegun before, but Sy taught me before he left, and I became quite good at it. For some stupid reason, I felt more secure with that machinegun than with a carbine. I knew if there was an attack, I would be the first target, but I still liked that gun. My machinegun fired .30 caliber bullets from a belt (more or less a bandoleer that ran through the weapon). And it fired a lot of them in a short time. It took two men to operate it--one, the bearer to sort of hand guide the belt into the weapon and another, the gunner, to aim the weapon and pull the trigger. One quirk was that if it got too hot, it would self-fire. The bullets would "cook off." That is, the heat of the weapon would detonate the shell without you pulling the trigger. Then it would continue to fire until it either ran out of ammunition or the barrel melted down and it exploded, whichever came first. To stop this chain reaction, the bear had to quickly pull one cartridge out of the belt. This interrupted the cook off. The advantages of it were that you could kill a lot of people with it. The disadvantages were that a lot of people were trying to kill you. There were two models of it--the air-cooled and the water-cooled. The air-cooled had heat fins on the barrel to dissipate the heat generated by the friction of the shells rubbing against the barrel. The water-cooled had a jacket around the barrel where water was pumped through it to take away the heat. You could fire a lot more rounds with the water-cooled than the air-cooled before you had to change the barrel. There is a reason why I was manning a machinegun instead of "doing something radio" when I first got to Korea. We were very close to the front. Only one hill and portions of the 1st Cavalry were between us and the enemy, therefore we had to maintain a perimeter guard during darkness. My machinegun was dug in a mud hole to give it all the protection we could. I was on a machinegun because I was a body. Nobody knew who I was in Korea. I mentioned that I had been transferred from Wire to Radio Company the day I was sent to Korea. Wire Company wasn't looking for me -- as far as they knew, I was still in Japan. The guys in the Wire Company knew, but just like me, they thought the brass was up on everything. Radio Company never got the transfer. I was a man without a country. Thank God I didn't get killed, for they might never have reported me. This got straightened out when we were pulled back to Pusan. Donnie WebbOn September 7, 1950, I located where my buddy, Don Webb was. He had arrived in Korea in early July of 1950. Since I had been on that machinegun all night, every night, I had no trouble getting permission to leave the area for a few hours. I hitchhiked to his company, the 16th Recon Company of the 1st Cavalry Division, and from there rode the chow truck to where he was. That was on the front lines. He was about 30 yards up from the edge of the Naktong River. The enemy was on the other bank, but because fighting always happened at night, there was no rifle fire going on when I arrived at his unit. There were some dead Koreans in the river, but no dead Americans. Their bodies had already been removed. Ironically, there was also a dead horse there with all four legs pointing up. I asked, "What the hell? Is the Cavalry shooting their horses? Who shot that horse?" Some old boy said, "I did. He came loping up in the middle of the night, and I told him to halt. He didn't, so I shot him. Guess he didn't understand English." I guess there is humor in everything. He only talked to me in a general way about what was happening on the front line. He said that so far the gooks (that was what we called the enemy) had kicked their ass, and that's about it. He didn't like it, but he also realized that he had signed on the dotted line too, and this was what he was being paid for. Don told me that they were coming back in on Sunday the 10th. Our time was limited since I had to return on the chow truck, so I swapped trousers with him (his had the bottom torn out and his skinny little ass was hanging out) and came on back to make preparations for Sunday. Again, I had no trouble getting permission to leave. I need to explain here that Don and I resembled each other very much. We were often taken to be brothers. We went along with it because we could have fun fooling people. That Sunday morning when I got to his company area and asked for him, all I got was people turning away from me and saying things like, "He ain't here" or "I don't know him" or "You're in the wrong place" and other stuff like that. But none of them would look me in the eye. It finally dawned on me that none of these guys wanted to be the guy who told Webb's "brother" that he was dead. I went back to my unit and wrote a letter to my mother to walk down the street and be nice to Mrs. Webb because Donnie was dead. As it turned out, he had been killed a few hours before I got there. I still cry about that. I'm getting weepy right now writing about it. For years and years I had a recurring dream of running into Don somewhere and finding out that he wasn't killed, but had been MIA all along. But if I was thirty when I had the dream, he was still 18. If I was 40, he was still 18. He never grew old. These dreams have abated lately. I haven't had one for several years now. I don't recall personally seeing any bodies of dead Americans while I was in Korea. I didn't even see Don's. I didn't know the names of any of the others who were in his company and who might have been able to tell me what happened. Besides, they were probably all dead, too.

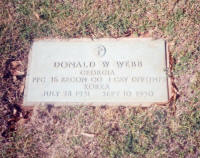

Point of interest -- Don was buried in Atlanta exactly one year after his death. He was killed on 10 September 1950 and buried 10 September 1951. He is buried in Westview Cemetery, just a couple of blocks from our homes. I have never visited the grave, but I have a picture of it. I just don't think I am man enough to visit it. I hate to cry in public, and I would probably make a spectacle of myself. And it would have hurt. When I got back from Korea, I looked up Don's parents. They had moved across town and I went there. Mr. Webb was, I think, in the hospital. He died a short time later. When I went in and faced Mrs. Webb, it was the first time that she had ever picked up on the resemblance between Don and me. she said, "Jimmy, do you know you look just like Donny?" I said yes and then she cried, and then I cried. As I said, I hate to cry in public, but I did then. I think I was crying for myself. I felt a great loss, great shame, and great guilt for still being alive. That is stupid, I know, but still true. Losing my best friend was the hardest thing for me personally about being in Korea. I have never really gotten over it. Few days go by that I don't have this tremendous feeling of guilt because I am still alive. I didn't make up any heroic yarns about Don. If I had started lying, then it would never have ended, so I told her the exact truth about my visit on the 7th and his death on the 10th. I just couldn't lie. Mrs. Webb died about a year later. Don had an older brother Robert who was in the Navy and had been in World War II. He is probably dead now. He had an older sister Martha who was very beautiful and I, like all the other young bucks around West View, had the hots for her--to the avail of none of us. He had a younger sister, Millie Sue, who had asthma and died when she was 21. Don's parents never blamed me for talking their son into joining the Army. They knew he had gone of his own free will and they, unlike my parents, had signed their consent. He was only 17 at the time. I think about blaming myself a lot, but I know that was the road untraveled, and I can't go back and take it now. When Donald Ward Webb was killed in Korea, the world lost a damn fine young man. He was amiable, friendly, and outgoing. He played tennis and the trombone. He had a real pretty girlfriend named Mary Ann Hornsby, who was Rogers Hornsby's granddaughter. Rogers was a famous baseball player. I ran into her after he had been killed and she was so beautiful she could actually stop a man in his tracks. She married a preacher and became a bible-thumper. Don had all the earmarks of being successful. Of the four of us who joined the Army that day, Don is dead, Bobby is in jail, and Thomas and I are relatively successful. No Laughing MatterWhen the 8th Army withdrew to Pusan right before I met SSG Crowe, they left the perimeter guard behind and I was in it. All our cooks had left to feed us with for several days were some GI cans (unused galvanized garbage cans) of sugar and flour. They made simple syrup with the sugar and pancakes from the flour. That stuff constipated us beyond belief. When I got to Pusan, it had been about four days since I had been to the latrine, and I was in agony. The first thing I did was turn in to the Medics. Now, notwithstanding all of the stuff you see on M*A*S*H, the Medics loathed and hated malingerers and goldbricks, but they treated the sick and wounded great. When I walked in that tent, I wasn't bleeding and I had not been wounded. I could see and feel their disgust: here was another damn goof-off. When I finally got to see the Doctor, he, too, was hostile. He growled something like, "What's your problem, boy?" When I told him and asked if he could give me something to make me shit (my exact words), he burst out in a laugh you could hear all the way back to Japan. I was damn near crying I hurt so bad, and I said, "Sir, I'm glad this amuses you, but I don't see a damn thing funny about it." He immediately sobered and apologized profusely. He said (and this is pretty near verbatim), "Son, I'm not laughing at you. I'm laughing at the situation. I've got a whole damn army out there wanting me to give them something to make them stop shitting, and here you come wanting something to make you start." He fixed me up though, and when I exited the tent, the hostility of the medics was missing. Needless to say, the next time I ingested a pancake was about thirty years later. Portnoy did, indeed, have a complaint. Analytical MindI didn't like or dislike my first job assignment. It was assigned to me and I did it. I did think it odd that Colonel Galusha wanted all of the radio operators he could get, and here I was in a mud hole operating a .30 caliber machinegun. But I damn sure didn't go to the CO and complain about my assignment. Come to think of it, I didn't right then know who the hell my CO was. I don't remember many of them. They weren't memorable characters. We had one Lieutenant we privately named "Porky Pig." He, in fact, turned out to be a knowledgeable and capable officer. We had made fun of him (not to his face) and given him the nickname back in Japan because he was fat. He thinned out considerably in Korea, though. There was Lieutenant Dillow. He had been my First Sergeant back in Company A. He had gotten a battlefield commission. I'll tell you more about him later. He was great. As stated, Cpl Sy Redding taught me about the machinegun. I would presume he survived Korea. He was a survivor. SSgt Charles W. Crowe (more about him later) taught me quite a bit about the SCR-399 radio, and of all things, cryptography. I didn't have a clearance for that (more repercussions from my streets of Atlanta days), but nobody ever asked me. There is one story you need to hear though. There was a big hill between us and the enemy. Each night at about the same time, somebody would light a fire on top of that hill, and then we would have incoming artillery. The shells sailed right over us into Taegu, where they created havoc among the refugees. The fire would go out and the shells would stop. One day a particularly dumb 2nd Lieutenant came out and asked me, "PFC Christiansen, do you believe there is some connection between that fire and the shelling?" I couldn't believe my ears, but I answered, "Goddamn Lieutenant. That keen analytical mind of yours has broke the code." He ignored my sarcasm, but a patrol was sent up there and the shelling stopped. First Three MonthsWhen I first arrived in Korea, the weather was blazing hot. To cope, we sweated a lot and showered whenever we could. I also "coped" by getting a bad case of malaria, which was kept in check with quinine pills until I left Korea. I suppose I got it on the machine gun. Next to our gun emplacement was a sump hole filled with old garbage, filthy water, and voracious mosquitoes. I had mosquito repellent issued and it was vile stuff, unlike "Off" of today. After a while, the smell abated and you got to where you could tolerate it. Unfortunately, so could the mosquitoes. We were made to take a quinine pill each day and I suppose that kept it inert until I went off of the quinine the next year in Japan. For the first three months, I was in every conceivable type of terrain. I never encountered any place that we were supposed to go that we couldn't get there because of the terrain. The truck was a 6x6, meaning it had six wheels that were each capable of receiving power from the engine. It was, and still is, in itself a powerful tool of war. I had no baptism of fire like front line troops had. I never fired my weapon in anger--my basic weapon was a telegraph key, which I "fired" a lot. The enemy was not dominant where I was, and I do not recall ever receiving direct fire. I was in a little hut on the back of a truck operating a radio. The hut was strapped to the bed of a two and a half ton truck. It had one door in the rear. Down the middle was a storage bin, which had cushions and also doubled as the seat for the occupants. On the same side, forward of the bin was the BC-610 transmitter. It was about a three-foot cube monster that weighed several hundred pounds and packed a lot of power. On top of it was an antenna tuner which coupled the antenna to the transmitter. The transmitter also generated a lot of heat which was hell during the summer, but wonderful during the winter. On the driver's side was another chest on the wall running the entire length of the seat. When this was opened, it became the "Operating position" (desk), and contained two receivers, the key, microphone, and other assorted gear. The hut could accommodate two operators, but it was much more comfortable with only one. Our team had pyramidal tent which had four sides that were vertical up to about 30 inches. From there they sloped to an apex approximately eight feet long. Inside we had four canvas cots, one to a side, and four sleeping bags. In the center we had an oil burning stove. The door opened on one man's cot, so we scrunched around so that we could still get in and out. All in all, pretty plush accommodations, considering where we were at. The Company Headquarters was stationary to a degree. It moved with 8th Army Headquarters and they moved according to the fortunes of war. The members of the company, grouped in teams, were all over the damn peninsula. We could go for months and never see our company headquarters. We got our mail on the few times that we came back to the company. Machine GunnerThe machine gun was manned only at night, and I was the gunner every night. I operated the machine gun from day two in Korea until sometime around September 11 or 12, when the battalion sent us to Pusan. Earlier, the 8th Army Headquarters moved south to Pusan. They felt that the North Koreans might break through the line. Most of the battalion had bugged out a few days earlier. They left us (the perimeter guard and a couple of cooks) behind. I don't know what they thought we could have done if the enemy had broken through. Then we were taken back. The Inchon Invasion had begun and plans for the breakout of the Pusan Perimeter were being formulated. They formed the entire company outside and started calling off names. They called off a sergeant's name and then three people were told to report to him. They had just made a "team." This continued until there was only one person left--me. They looked at their roster and finally came over to me and asked who I was. When I told them I was PFC Christiansen, they looked at the roster again, scratched their head, and asked what company I was in. I told them, "Radio." They asked how long I had been in Radio Company and I told them the date. (I knew it then, but I have forgotten now.) They told me to stand right there and not to move out of my tracks. After a while they came out and said they had found me and I was to go to my tent and await orders. Sometime later, S/Sgt. Charles C. Crowe came in, introduced himself, told me I was now on his team, interviewed me about my background, asked whether I was a Private or PFC. When I answered PFC, he walked right out of that tent and, I found out much later, had me promoted to Corporal. I don't know why--I suppose I had impressed him. I was now on my first team, and had actually become a person as opposed to the non-person I had unwittingly been for about a month. As to the telegraph key being my basic weapon, that was just my way of saying that I was a communicator--a good communicator--and not a hero. I certainly wasn't one of those. I stayed on S/Sgt Crowe's team as a radio operator from September through October. Top Secret TroubleFrom September through October, while I was a radio operator on SSG Crowe's team, the first UN offensive was taking place. Early on, before Inchon, I was afraid we might be pushed out into the sea. Really, I feared for my life. The Inchon Landing then occurred, causing the enemy to panic and make wild retreats toward the north. The 8th Army broke out of the Pusan Perimeter and gave chase, seeking to trap and destroy as many of the enemy as it could. Wire communications over long distances became impossible while we were in that posture, so Radio company had to send teams to all of the major units of the 8th Army. These were the teams that had been made up that day in Pusan when I was "discovered." The major thing that happened to me was that I was learning how to be a radio operator. I had been trained as an operator in Camp Gordon, Georgia, but this was the first time that I had ever been called upon to use that training. Morse code is a sort of "use it or lose it" situation, and it had now been about 15 months since I left Camp Gordon. My skills had decreased greatly. I did have several run-ins with SS Crowe. He was, indeed, as I had been warned, a horse's ass. But he was a smart horse's ass, and he taught me well. At that time, I was eager to learn anything that I could. I would have attended a school for the treatment of post nasal drip and hangnail if they would send me. I sensed that Crowe, despite his crude personality, knew what of he spoke, and I hung on his every word. Crowe yelled at people and belittled them in front of others. He had many personality shortcomings, but he was a good radio operator and teacher. Our team went wherever the Commanding General, Lt.Gen. Walton H. Walker, and his staff went. The most notable (scariest) thing that happened to me was that one night I inadvertently opened a Top Secret envelope that was meant for the staff. A courier inadvertently delivered it to me. It was night, and I was on duty in the hut when the courier knocked on the door. I hated opening the door at night, because you never knew who you were opening up for. But I did, and the courier thrust the envelope in my hands and had me sign for it. Being as inexperienced as I was, I thought it was something for me to send, and I opened it. I quickly saw my mistake. When I saw what I had done, I timidly walked into the command tent and surrendered the document and confessed to what I had done. I thought that they would probably shoot me, but they tut-tutted me out and the incident was forgotten. I'll bet that courier caught hell when he turned in his receipt and they found out that he had delivered a top secret package to PFC Christiansen. After that, I was a Team Chief for the Net Control Station of a net controlling train and supply. Why they chose me for this job, I'll never know. There were a lot more capable and more experienced operators than me, and I was just twenty years old. I was a PFC--or so I thought. I didn't know that I had been promoted to Corporal. "Me and Bobby McKee"From October until Thanksgiving, we were moving toward Seoul and I was a team chief. The holder of that position was responsible for the overall operation of the team. He scheduled the operators, saw to it that all of the equipment works, took care of the welfare of the men, etc. In short, he was the "Sarge in Charge." By the time we got to Seoul, the enemy was in full retreat, and we were told that we would be "home for Christmas." This whole interval was before the Chinese intervention, when we were kicking North Korea's butt. Here is an interesting bit of history for you that has absolutely nothing to do with this narrative:

The war there in Seoul was over, or so we thought. The mission of those in Seoul was one of resupply. Since the telegraph lines along the Korean Railroad system had been destroyed, radio teams were sent to major towns along the route to dispatch and control the trains. I was given a SCR-399 and all of its appurtenances, three men, and sent to the Seoul Train Station to take charge of this operation. The station, oddly enough, looked almost American. It was a depot with granite floors and indoor plumbing. Pretty fancy accommodations for a soldier at war. We only slept, ate, and used the indoor plumbing in the building. We worked outside in our SCR-399, which was parked nearby. Again, why I was chosen to oversee operations was, and still is, a mystery to me. I was woefully unprepared. (With age comes experience and knowledge. Being only 20 years old, I had neither of those things.). I had actually been a radio operator only a few weeks since SSG Crowe had picked me up. It was an awesome responsibility, and I didn't think I was up to it. Here is a glaring example: I couldn't even drive. My family was extremely poor and had never owned a car, ergo, I never had the opportunity to learn. They didn't have driver training in school then. I finally learned to drive in 1952 when I was back in Camp Gordon. In Korea, I always had to have somebody drive for me. I felt like a damn fool. To top that, one of my three men was a new replacement from Camp Gordon named Corporal Robert McKee. My own man outranked me. He and I were told that I was a known quantity and he was an unknown, and that was how it was going to be. He had no objections; I think he was sort of relieved that he didn't have the responsibility. I couldn't object, but I sure as hell questioned the intelligence of it. In the end, I did what I was told to do. My biggest challenge in the job as Team Chief was gaining self-confidences. The actual mechanics of the job were a piece of cake, except for the driving. McKee and I became fast friends, and later he, along with Ralph Graham, Jr., were sent back to Japan with me to become instructors. The job of controlling the net went without major incident. One day, I was told to return to the company to draw winter clothes for the team. After being issued the clothing, I had to sign for them, and the supply people couldn't find me in their records. I thought, "Oh hell, here we go again." They scoured through their roster of PFCs and couldn't locate me. Finally, in desperation, they looked through the Corporals. There they found me. I had been a Corporal for about two months and hadn't known it. I took some corporal stripes and went on back to the station. One good thing came of this. The camaraderie between "Me and Bobby McKee" (that sounds like a song, doesn't it?) became distinctly better. There had been no friction, but still I had felt uneasy giving him orders. One notable (at least to me) thing happened during this period. The state of the war at that time being what it was, the army began to reward the soldiers. Train loads of beer arrived in Seoul, and it was announced that on such and such a day, at such and such a place, each soldier would be sold two cases of beer. You had to buy it individually--you couldn't buy for someone else. That meant four trips for the team. I left McKee in charge and went first. Rank has its privileges (especially new rank) and I was going to get my beer. There was an extremely long line into this building, and I was about half way when we noticed a dog sniffing and crying around a little outbuilding. That in itself was strange enough because the Koreans ate dogs and you didn't see many of them loose. The building looked to be about eight feet square and around seven feet high with one door. Nobody was willing to give up their place in line to investigate, but I negotiated. If they were willing to guarantee my place back in line, I would go look. Agreed. When I opened the door, I wished that I had stayed in line. Tumbling out of that door, like balloons at a Halloween party, came hundreds of human heads. The Koreans believe that if you do not have a head, you cannot find your way into heaven. Thus, beheading was a particularly cruel way to execute people. The North Koreans had executed many South Koreans during their stay. I don't know what they had done with the torsos--I never saw them. The line got considerably shorter as the weaker among us vomited all over the place. I returned to the line and stayed and got my beer. I just put it down as one of the horrors of war. The net remained in operation until about a week before Thanksgiving. A net is a grouping of several radio stations together for a common purpose. Any net has but one net control station. All the other stations in the net are subordinate to it. They must request its permission to speak to one another. The net control can order a change of frequency (the spot on the dial) or mode (Morse or voice) or can command radio silence. The net control is the operator on duty at the net control station. As such I and my operators were giving direction to people who outranked us. I didn't like that one bit. I did then and I do now strongly believe in the chain of command. As I said, the teams returned to the Company around Thanksgiving. There, I being just another Corporal with precious little actual radio experience, was reassigned to SSG Ralph Graham, Jr. of Memphis, TN. We were eating our Thanksgiving meal when they came and got us. The following period under Ralph Graham prepared me for life more than any of the others. |

|||||||||||||||