The Sinking of the USS Magpie

Our ship was the USS Magpie AMS 25 and our home port was Guam. The Magpie was a small wooden-hulled yard

minesweeper with a crew of 32 officers and enlisted men. On June 25th, 1950, when the Communists overran the 38th

parallel, I had been aboard the Magpie about one year having come aboard in Pearl Harbor when the ship was there

for a yard overhaul. When the push across the 38th parallel began, the Navy department, as a precautionary move,

assigned our mine sweep division, then in Guam, to perform submarine patrol across the mouth of Apra Harbor. Along

with our sister ship the USS Merganser AMS 26, we performed that rather boring duty from June through September of

1950. Every other day we were out there idling back and forth across the mouth of the harbor with sonar running.

About the first of September, the division received orders to proceed to Sasebo, Japan, and then to Korea. We

departed from Guam on September 17, 1950. The Magpie and the Merganser traveled independently to Japan, and we

rejoined again in Sasebo.

The Magpie’s passage northward was a rough one. We rode the tail end of a typhoon most of the way north. It

became so rough that our skipper Lt. (jg) Warren Person decided when we approached Iwo Jima to go to the lee side

of the island and let the typhoon go on north. Iwo Jima has sulfur beds on it, and as the wind blew over the

island, it came directly over the ship. It was a toss-up which was the worst--the rotten egg smell of the sulfur

or riding the tail of the typhoon. After two days, we proceeded on northward and as we approached Japan, we sailed

around the southern end of Kyushu through the Van Diamond straits, if my memory is correct. There was a full moon

and the seas were like glass. I went back on the fantail and the wake of the ship boiled up for about fifty yards

back, then flattened out. You couldn’t have told a ship had passed there. Small Japanese fishing boats, with

lanterns hanging over the side as they fished, dotted the sea. It was a gorgeous night.

We arrived in Japan on September 27, 1950. We had some main engine problems on the way north so we lay

alongside the dock for two days and repaired the engine. We refueled and took on a full load of ammo. We rejoined

our sister ship, the USS Merganser, and left for Korea on September 29. On the morning of September 30, the sweep

division proceeded to an area on the East Coast of Korea approximately one hundred miles north of Pusan, and swept

a path northward for about fifty miles. We cut one mine loose and the Merganser shot it. It didn’t explode, it

just sank. During the first night, we ran at half sped further north. On the morning of October 1, the division

turned round and streamed our sweep gear toward the beach and headed south. We ran that way all day. The Merganser

was out board of the Magpie and about five hundred yards astern. We ran in tandem all day in the water that we had

swept the previous day. About 1600 hours, we reached the arc we had come in on the previous day, and as we hadn’t

cut any mines, the decision was made to proceed further south. As we moved south, we began to see what some on the

bridge said were mines. Down on the deck level, they appeared to be huge jellyfish. You could see tentacles

stringing out of them. It was now 1700, and time to eat. Most of the crew was in the galley or in line to go in.

At this point, we were steaming along a line of steep cliffs. Later, they said we were in an area called ChuckSan

Dong or Chosen Po. We were never certain of its correct name.

For those that are familiar with the process of sweeping mines, it is to start out in deep water and sweep a

path with the sweep gear out toward the shore. The ship then turns around and while traveling in a swept path,

streams the sweep gear over the other side toward the shore. In this manner you work your way into the beach and

clear an area of mines. Mines are normally set to demolish large ships by anchoring the mines on cables attached

to concrete blocks well below the surface of the water so a large ship, if it hit it, would take the hit below its

amour belt and do it the most damage. Mines are not aimed at small ships like the Magpie. The hitch in Korea is

there is a tide well in excess of 40 feet. It is one of the highest tides in the world, second only to the Bay of

Fundy off of the northern coast of Maine and Halifax, Canada. Those that have seen the harbor at Inchon empty of

water can attest to this. Here is where the relevance of this applies. When we hit the mine, we were steaming

along with the understanding that we were traveling in swept water, when in fact we were forty feet deeper in the

water than we had been the previous day when we started that path.

It was late in the afternoon on that October 1st day, and the crew had lined up to go to chow when suddenly an

American P47 Corsair popped out from over the cliffs and right over the Magpie. It turned out the pilot had been

bombing on the beach someplace, got a bomb stuck in his wing rack, and he flew out to sea to dislodge the bomb.

When it suddenly appeared, the skipper set general quarters. Everyone ran from the galley toward their battle

stations As soon as they recognized the plane was an American plane, they secured battle stations and like all

sailors will, everyone ran back to get back in the chow line. I stayed back at the engine room hatch and watched

the plane cut diodes over the ocean to dislodge the bomb. He finally did, and the bomb blew up in a cloud of black

smoke and the plane left. Three minutes later, we ran into the minefield. Later, aerial photographs showed that we

hit a thousand-pound mine. There were three of them on a single mooring, and we took out the middle one. When it

blew, the line of concussion completely blew the bridge away. All of the officers and personnel up there were

killed instantly. The most forward section of the bow, which was right above the mine, blew away and traveled

maybe a hundred yards aft of the ship and landed in the sea. There were two guys that had been standing on the

point of the bow. They climbed back on the wreckage, and we later picked them up. When the mine blew, it also blew

up the main magazines. We had taken on a full load of ammo in Sasebo, plus a thousand pounds of TNT in five pound

blocks for demolition of the ship. The end result was the mine and the magazines blew away 90 feet of a 136-foot

ship, blowing it into splinters.

I was standing at the top of the main engine room hatch when we hit the mine. For some reason, I started to run

forward up the starboard side of the ship. I got about even with the generator room hatch when the magazines blew.

I remember looking up and seeing a deck hand named Eugene Krouskoupf running toward me, followed by several other

guys. He was about even with the hatch to the officers’ quarters when the magazines went up. There were tracer

shells flying everywhere. I thought we were being strafed. The magazine explosion knocked me down on the deck. I

lay there on my knees with my head on the deck and my hands over my head. Tons of water full of black powder and

all kinds of debris were falling on top of me. I got black powder in my mouth and the taste of cordite lasted for

weeks afterward. Krouskoupf and the guys following him never made it through the second explosion.

As I lay there with all of that water and debris falling on me, it dawned on me that this was not the smartest

place to be, so I ran back to the main engine room hatch cover. The hatch had fallen down, so I jumped in under

the hatch cover. I had no more than got in there when another engineman, Jim McClain, came running by. I reached

out and grabbed him and pulled him into the hatch cover with me. Just as I did the entire top of the cargo boom,

which stands about three feet aft of the main engine room hatch came crashing down where McClain had been. We just

stayed in there and held on. The Merganser crew later told us the rear portion of the ship stood up on its end and

then settled back into the water.

When everything quieted down, we crawled out and found the few that were left. What was left of the ship lay

with the wreckage of the forward part hanging down into the water. Everything forward of the ship’s stack was gone

and the stack itself was half submerged. All of the life rafts were destroyed except one. We unlashed it and a

gunners mate named Harrison and the Chief Boson Mate Carpenter began yelling to abandon ship. We threw the life

raft over the side and found life jackets for those that didn’t have one on, and we jumped into the water. There

wasn’t room on the raft for all twelve of us, so we put a seaman named Benson in the raft as he had a badly hurt

ankle and couldn’t swim. The rest of us hung onto the lines around the raft. We also were afraid the remainder of

the ship was going to sink and we might get tangled up in the debris and get pulled down with it, so we moved off

a ways and waited. It is strange the things you remember in times like that. I recall while in the water--it was

the first of October and the water was very cold--water kept slopping up over the neck of my life jacket and

hitting me on the hollow of my throat. I kept pulling the collar of the jacket up to keep the water from doing

that. There I was submersed up to my neck anyway and I was trying to keep it from hitting me on the throat. In a

few minutes the USS Merganser sent a boat over and took the life raft in tow. As we started back to the Merganser

we heard someone hollering. It was only then that we realized the two guys on mine lookout had survived. The

Merganser boat went out to the wreckage of the bow and picked up the two guys that had crawled up on it. The boat

took them to the Merganser, and then came back and towed us to the Merganser. When we hit the mine, the Merganser

had stopped dead in the water and was just setting there about 100 out board and 500 yards aft of us.

The story of the two guys that were on the wreckage or the bow is a story in itself. These two guys’ names I

can’t be sure of. I think one of them was Hank Blassinggame and the other I am not sure of. These two guys had

been on mine lookout setting on a folding chair right on the point of the bow. The bosons had rigged a canvass

around the railing to protect the watch from the sea that blew over there and put a chair there to set on. The

watch had some binoculars and headphones connected to the bridge, and would set there and look down in the water

ahead of the ship for a mine. They were just relieving the watch. The one relieving was raising the binoculars to

his eyes when the mine went off about 20 feet below him. They were so close to the point of the explosion that

concussion carried the bow and them aft of the ship and they suffered no ill effects of it at all. One of them

later told us his gloves shot off like a banana coming out of its skin. They even remembered seeing the ship as

they pasted over it. It is amazing what a person will remember in a split second like that.

The boat towed the life raft, with us hanging on to it, back to the Merganser. They dropped a rope ladder over

the side for us to climb aboard on, but most of us couldn’t do it. My clothes were water-logged, and I felt like I

weighed a ton. A Merganser sailor climbed out and stood on the outside edge of the deck and leaned down as far as

he could. He would grab hold of the back of our shirts, pull us up, and throw us over the rail onto the deck. I

hit the deck like a sack of old dirty laundry. I had no strength, my lower jaw was shaking, and my teeth were

clicking together. I tried to put my hand on my jaw to stop the clicking, but couldn’t do it. The guys from the

Merganser started to tear off our clothes to get us out of the wet clothes. I told them to take it easy, that

these were all of the clothes we had. We stripped down, and the Merganser crew shared dry clothes that they had

with us. I don’t think I ever got my own clothes back. We all gathered on the fantail, and the Merganser skipper

came out with a bottle of whiskey and gave each of us a shot. It was the best-tasting stuff I ever had. My jaw

quit clicking, and soon we were up and moving around. The Merganser captain had his entire crew, plus us, come

back to the fantail, and someone from that crew volunteered to steer the ship out into deep water and out of the

mine field.

The Merganser took us down to Pusan, where we were put aboard the hospital ship the USS REPOSE. Most of us were

just cut and bruised. I had a scalp wound from the debris falling on me. They took a few stitches in my scalp, and

I was all right. We stayed on the Repose for two days, and then someone from the Merganser showed up and said the

Merganser was going back to Sasbo and we could go back with them. I think eight out of the twelve went. The other

four had more serious injuries and stayed for a few more days.

Another incident happened when we got underway on the Merganser. They were out of Pusan and it was dark.

Somehow when the ship changed course, the steering gear locked up. The ship just kept turning and would have run

in circles. They stopped as soon as they realized the ship wasn’t responding to the helm. They came to me and

asked if I would help their guys with the problem. I guess it was because I had worked in the main engine room on

the Magpie. I was very reluctant to go below decks, but I did. We went into the aft steering compartment and found

one of the big steering cables had jumped out of its track. We set up a talking device so we could talk to the

bridge, and as they eased the helm we hit the cable with a big sledgehammer and it went back into its track and

all was okay. It was not a major thing, but the thought went through my head that we had just lost one ship and

didn’t want to lose another. None of us would go below that night and we slept on deck all night. We got back into

Sasbo the next morning and they put us aboard the USS Dixie, a destroyer tender that was anchored in the harbor

and used as a receiving station. The Magpie was the first US ship to be sunk in wartime since WWII, and they

didn’t know what to do with us. We had no medical or pay records of any kind. There was mail there for the ship,

but a commissioned officer had to sign for it. We had only a Chief boson Mate as our highest-ranking Non-com. They

said all of the ship’s mail had to be returned to the Navy Department in Washington DC.

In sick bay, we told them we had taken all of the required shots before we left Guam to be in the area around

Japan and Korea. They said, "We have no record of it, so let’s do it again." So we lined up in sickbay and walked

between a line of hospital corpsman. They hit us in both arms at the same time. We took all of those shots again

in one morning. They issued us two pair of whites, blankets, and a liberty card. We would catch the first boat

ashore each morning, and the last liberty boat back each night. We weren’t attached to anything, so we just went

on liberty for about one month. We were then put aboard the USS Piedmont, AD17, and on November 15, left for

Yokosuka and on to San Diego and leave. The ship arrived in San Diego December 1,1950, after fifteen days at sea.

I had been overseas for two years. We didn’t have much money, so some of us went out to the Naval Air Station.

There, we found a reserve crew that had flown out to the west coast to log air time and were going back to

Oklahoma that afternoon. They agreed to let us go along. We boarded and found it was a cargo plane that only had

jump seats along the bulkhead. That was not the worst of it. After they were airborne, they found that the heating

unit for the cargo space didn’t work. The only heat in the plane was in the tiny pilot’s compartment. It was the

first of December and cold as heck outside. So we walked up and down inside that cargo plane all night long to

stay warm. Every once in a while the pilots would let us, one at a time, come in and lean over the co-pilot, put

our hands on the instrument panel so we could close the door and get warm. After a few minutes we had to get out

and let some one else in. The plane finally landed about 4:30 at the reserve air base called Tinker Field. The

place was empty. The crew taxied the plane to an area and got in their cars and left. There we were and didn’t

know where the heck we were. We finally Searched around and found an exit and a coffee shop. We called a taxi and

he took us to the commercial field in Oklahoma City where we got a TWA flight into Kansas City. It was a long

night going home after all we had been through.

Not being able to get our mail after the ship sank caused me other problems. I had taken the fleet exams for

Engineman third earlier in Guam. I was pretty sure I had scored well on it and the postings were due out. But I

couldn’t find out anything. At my next duty station at COMPHIBPAC in San Diego, I told a Yeoman friend about this

and he got his boss to write to BUPERS. Sure enough, I had made it. They agree to promote me, but wouldn’t give me

the back pay. Not only had I lost everything I owned, but I also lost the back pay too.

This account is to the best of my recollections. I stayed in contact with my buddy Jim McClain over the years

and was sadden by his death in the late eighties. This year, 2003, after 53 years I made contact with two other

Magpie survivors, Howard Kastens and Alex Bennett. We have also found an ex-ship mate, Ed Clanton that did a tour

on the Magpie and got off her in Pearl Harbor just as I got on. It has been a real experience sharing "sea

stories" with these shipmates and all of us have great hopes we will be successful in finding the other survivors

of the Magpie crew. We know out of the twelve survivors that three have passed away so there are six out there

somewhere and we hope they will contact one of us if they read this.

There were 32 officers and enlisted men aboard the USS Magpie. Twelve of us were fortunate enough to have

survived the incident I described. Hardly a day goes by that I don’t think about the time we lived and worked

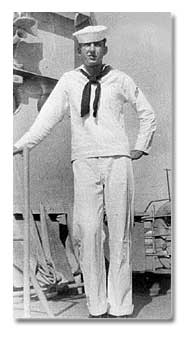

together and the moment we hit that mine. Click this link for a larger image of me standing

on the deck of the USS Magpie.

There were 12 survivors of the sinking of the USS Magpie, and Terry is in contact with two of them, Howard

Kastens and Alex Bennett. A third survivor, Thomas D. Dobbs, has been located with the assistance of the Korean

War Educator. Although not a survivor of the sinking, Ed Clanton served a tour of duty on the Magpie. He left the

ship in Pearl Harbor at the same time that Carlock boarded her, but he remains very interested in the Magpie, and

is involved in the search for others who served on the ship. Survivor James McClain died in 1989. Carlock believes

that survivors James Kepford and Richard Benson also have died in recent years. Names, ratings and service numbers

of other survivors at the time of the sinking are: Vail P. Carpenter BMC 393-08-57; Dobbs ETSN 325-16-58; Leo L.

Espinoza; William E. Harrison GM3 234-41-27; Henry A. Blassingame CSSA 581-07-35; and Howard W. Sanders QM3

570-94-48.

Casualty List – USS Magpie

Editor’s Note: List provided by Ed Clanton of North Carolina. Ed went aboard the Magpie in

February 1948 and transferred off in September 1949. Ed tells us that Guam was listed as the home of several

casualties because their families were based on Guam when the accident happened.

Warren Roy Person, Lt (jg), Commanding Officer, Pacific Grove, CA

Stanley Louis Calhoun Jr., FN, Dunkirk, IN

Robert Warrell Langwall, ENS, Indianapolis, IN

Harry E. Ferrell FN, Cleveland, OH

Charles T. Horton, SN, Columbiana, AL

Eugene P. Krouskoupf, SN, Zanesville, OH

Charles Russell Bash, SN, Dixonville, PA

Roy A. Davis, HM1, Russellville, KY

Richard D. Scott, BM1, Peru, IN

Robert Ernest Wainwright, ENS North Andover, MA

Seth Dean Durkee, QM1, Cashmere, WA

Robert A. Beck, Guam, M.I.

George Grady Cloud, EN1, Guam, M.I.

Theadore Amos Cook, SN, Sacramento, CA

Leonard A. Coleman, YN3, Fuente, CA

James Claymore Dowell, FN, Richmond, VA

Vincent Q. Fejaran, SD3, Asan Village, Guame, M.I.

Lloyd E. Hughes, CS1, Ottawa, KS

Cleveland G. Rogers, SO3, Guam, M.I.

Donald Victory Wayne, Lt (jg), Gardena, CA

More About Terry Carlock

Dale Terry Carlock of Tyler, Texas, born 1925, a son of Charles and Iva Carlock, died August 19, 2007.

Mr. Carlock was one of the 12 survivors of the sinking of the USS Magpie during the Korean War. His memories

of the sinking are available for viewing on the KWE's Memoirs page. He was discharged from the Navy in June

of 1952.

After discharge, Terry Carlock worked in an oil refinery before eventually going to an IBM school to learn how

to operate punched card equipment. He worked for two companies in that field, and then got a job with the Mobil

Oil Corporation. With Mobil, he graduated into computer programming when they came into widespread use. Mobil Oil

became his career company and computers his career vocation. He worked all over the United States. In 1975, he was

transferred to the Exploration and Producing Company of Mobil Oil and was sent to Nigeria in a management

position. His wife Iola went with him, and they lived in Lagos, Nigeria, for four and a half years. In 1980, they

were transferred to Medan, Indonesia. Medan was the provincial capital of North Sumatra. After one year, Mobil

transferred the offices to Jakarta on Java, and Terry and Iola lived in Jakarta for five and a half years. In

1979, Mobil brought Terry back to the United States to Dallas, Texas. He elected to retire in 1980, and returned

to California, living north of Santa Barbara at Santa Ynez and then Lompoc. In 2001, he moved to Las Vegas,

Nevada, and later he moved to Tyler, Texas.

He was preceded in death by his beloved wife Evelyn Iola Carlock, his parents, and his brother Donald Lee

Carlock, He is survived by daughter Teresa Plowman and her husband Michael of Broken Arrow, Oklahoma; his

son Brett Carlock and his wife Paula of Las Vegas, Nevada; his stepdaughter Linda Tye of Oak Grove, Missouri; his

two sisters, Jo Ann Hall and her husband Jim and Wanda Rowan, all of Independence, MO; three grandchildren and

three great grandchildren. He was cremated and buried at a later date. |