|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||||

Herman Ross BrummerPleasant Valley, NY- " I often exchange stories with comrades who fought in Korea. Most of my stories, however, detail humorous experiences and general conditions. Only rarely do I mention the horror of war. It was and is too difficult for me to talk about. Some of the sights that I saw were devastating and it did not make for polite discussion." - Herman Ross Brummer

|

|||||||||||||||||

Memoir Contents:

PreludeBefore I begin my personal account, I would like to submit some material given to me by Robert T. Warring, father of my best friend in service, John Warring, who unfortunately died a few years ago of cancer. Even then, Mr. Warring thought I might one day write my memories of my experiences in Korea and thought his research might help me.

Note: These comments were made by Mr. Warring, and though I generally concur, some of the information I had no personal knowledge of, or more likely, simply don’t remember after all these years. I am pictured here with John Warring when we were both in the military. Pre-Military BackgroundI was born June 4, 1928 in Bronx, New York, the son of Jack and Dorothy Abramowitz Brummer. I am an only child because my mother had a rheumatic heart and was told that another child might kill her. My mother was a published poet, but did not write or work outside the home after she was married. Originally, my father was a musician (a violinist) with his own orchestra. He once played in the New York Philharmonic. He also played in the pit at movie houses when there were silent movies. The pit was a depression in front of the screen. The musicians sat in this depression or pit (it was low enough not to interfere with the patrons' ability to see the movie). The music was meant to appropriately accompany the movie. After the depression hit and sound movies came in about the same time, he found himself out of work. He then became a machinist working for International Projector Corporation (I.P.C.). He left that position and opened up his own machine shop with his brother-in-law, Charles Peskin. The company name was Jaycee Manufacturing Company (Jack and Charley = J/C). One important item that made me very proud of my father was the fact that he was offered a lot of money to make items for the black market. I don't remember exactly what it was, but I know it was metal products that most people could no longer purchase because metal was needed for manufacturing defense products (weapons, planes, etc). He refused, saying that American boys were giving their lives for this country and he would do nothing to undermine their efforts. The company made items for the government under contract. Since they had only a small machine shop, the items were small out of necessity--often only a part of a larger item. When the war ended, he lost his contracts and closed the shop.

My father then became a watch repairman. He originally started watch repairing as a hobby, often fixing watches for relatives and friends. He had a little shop in a spare room of our house. Later, when he left the machine shop, he opened up a watch repair shop in a small store. It was merely called Watch Repairing with his name under it. He did this alone, though sometimes he accepted watches from jewelers who sent him watches that customers brought in. One such store was called West End Jewelers on 86th Street in Brooklyn, New York. He stayed in that job until his death. I went to Public School 52 and Public School 24 in Brooklyn (Williamsburgh). When we moved to Bensonhurst (Brooklyn has sections with different names), I went to Junior High School (can't remember the number, but the name was Seth Low). I followed that by going to Lafayette High School where I graduated in 1947. While I was in high school, I worked for my father in his machine shop. I also worked as a messenger in Manhattan. I did a variety of other odd jobs, including working in a clothing store, and later as a file clerk and typist for Pal/Personna Razor Blade Company. World War II was going on when I was in high school. My cousin Morris was a Marine and was on Iwo Jima when the famous flag picture was taken. In fact, he was a guard at the base of the hill where the flag was erected. There were other cousins in service at that time, but I know nothing about their experiences. I remember bond drives. As students, we were given books where we could put stamps (that we paid for) on the pages. When the book was filled, we turned it in for a defense bond. I was also an air raid warden. We had test blackouts, and I walked a particular route to make sure that there were no homes with lights on. I also worked with my father on defense contracts. One was making the lens mount for the Nordan Bomb Site. We didn't know what it was initially, but we found out later. After I graduated from high school, I entered Brooklyn College in the afternoons and evenings in 1947. I joined the Phi Beta Upsilon fraternity, later became president of the frat, and later still became president of the Inter-Fraternity Council, which included all frats on campus. I was not sports-oriented, though I did belong to a fraternity bowling league. I also joined the National Guard that same year. It wasn't meant to be patriotic at the time. It was my mother's idea. She was frightened about the draft and thought that joining the National Guard would allow me to finish college. I was an obedient son and did what she wanted. The Korean War interrupted my studies, but my major before and after the war was English. My minor became education after I was inspired by a wonderful professor. Initially, I had no specific career plans, but this eventually evolved into English teacher. War Breaks OutI joined the 955 Field Artillery Battalion Guard unit in Brooklyn. We met at the 14th Street Armory in Brooklyn (which was a famous armory during past wars) once a week. I went with them for two weeks every summer and one weekend a month the rest of the time. We went to Pine Camp (now called Camp Drum) in upstate New York. It was the only camp near us that had an artillery range. There, we had training in weapons, battle tactics that were appropriate for artillery, and general Army stuff like parading, hiking, close order drills, etc., all of which seemed like nonsense to most of us. We were a 155 Howitzer group. When they found out that I was a "college boy," they eventually had me work in the office, though my training was the same as the others. Initially, I was in the motor pool, until they decided that I would be more useful in the office. I have several pictures from my National Guard days. |

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

| When the Korean War broke out, I knew nothing about Korea, and I had no idea that I would ever be

part of the war. I did not want to go to war. I hated war then; I hate war now. I know that my

mother was devastated. She blamed herself because it was her idea that I join the Guard, keep out of the

draft, and finish college. I don't know how my father felt. He was somewhat reserved, but when I

returned he showed how proud he was of me. My adventure, if one might call it that, began when the 955th Field Artillery Battalion was activated and I was sent, along with my buddies from the 14th Regiment Armory on 14th Street and 8th Avenue in Brooklyn, New York to Fort Lewis, Washington. We boarded a troop train and took a very boring five-day journey to Fort Lewis, Washington. The worst part of the trip was when we reached the Chicago yards. We came in on the track at the far right. For the next five hours, our train backed up, moved forward, backed up, etc., until we arrived on the track at the far left, and then we were able to proceed to Fort Lewis. We finally landed in Seattle, boarded trucks, and proceeded to the Fort. The only real memory I have of the Fort is that I got there in the fall and it rained almost every day. I went to the post movies, got weekend passes into town, and was generally bored out of my skull.

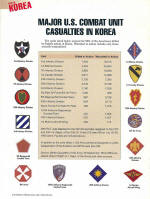

We received further training while we were at Fort Lewis. One such event was crawling through mud with live machine guns firing over our heads. From time to time, preset explosions occurred, but these were not dangerous (not exactly sure why). At one point, I stopped over a mud hole and noticed to my left that there was one of these explosive charges. I knew it would go off, and I steeled myself in anticipation. However, when it did explode, I ducked my head--you know it--right into the mud hole. I also spent time hiking, as well as firing on the rifle range. (I got my first bull's eye there.) Other duties of mine included guard duty and working in headquarters office. After about five months at the Fort, we boarded a troop ship and headed for Korea. Just before being shipped overseas, I came home on furlough. I don't remember exactly, but it was either one week or two. I flew home--my first trip in a plane. While there, I gave my cap to my closest friend, Artie, to try on. He balked, saying that he didn't want to get even that close to the Army. Nevertheless, the war also caught up with him, and I later met him in Seoul at the 5th Air Force headquarters. While home on furlough, I said goodbye to my girlfriend, friends, and parents. Trip to KoreaI don't remember exactly when I left for Korea, but it was in the late fall. I was a Corporal at the time. After returning to Ft. Lewis by airplane, I shipped overseas on a huge transport ship named (I believe) the A.E. Anderson. It held thousands. So far as I know, there was only Army personnel aboard except for some Marines who were there to act as guards/security. I believe that the only cargo aboard had to do with equipment that we would need--guns, vehicles, etc. I remember very little else about it, except there were no seats in the mess hall. We ate standing up at tall tables. They were very long and about forty men stood around each of them. At one point when the ship dipped to one side, all of our food trays flew down one side of the table. When the waves changed the course, the trays came back. I was at one end of the table and saw forty or so trays bearing down on me. End of eating. This was the first ship that I had ever been on. A Marine aboard corrected me when I called it a boat. I had no problem with seasickness. I guess I am a natural sailor. This was not true about other soldiers aboard. An amusing incident occurred when I was in the bathroom and during a time when we had hit some rough weather. The bathroom was completely filled with very ill men. One of them offered me money if I would get up and let him take my place. The only "entertainment" (if you can call it that) on the ship was gossip and speculation about where we were going. We hadn't been told officially that Korea was our destination. Some had it on good authority that we would go through the canal and end up in Germany. I can also remember that there were movies topside, and I worked in headquarters office on the trip where I filled out "Morning Reports" for the most part, and took care of the 201 files. A 201 file contained all pertinent information regarding enlisted men. There was a comparable one for officers, but I never saw one. The 201 file contained his MOS (Military Occupational Specialty--his job), dates of enlistment and/or activation, social security number, contact information, family, etc.--in short, anything that could be useful regarding a soldier. I knew many of the boys on the ship since we came from the same outfit in Brooklyn. I also had a personal friend, John Warring. There was no training onboard the Anderson, and nothing eventful happened during the trip, except I remember that the Marines jumped ship so they could go to Korea instead of Japan. I did not know much about this, but I understood from others that they wanted to get into action and not merely perform as "policemen." I'm not sure exactly what was meant by "jumping ship" or how this was accomplished except that in some way they planned to go directly to Korea. We stopped over in the Tokyo/Yokohama seaport for about two days (I don't know why), and then left for Korea. While at the seaport, all enlisted men had to stay onboard. Some of the officers went into Tokyo/Yokohama, but I did not go to Japan at that time. Korea: In the BeginningWe arrived in Korea during the daytime, but I do not remember if it was morning or afternoon. We got off the ship in a reasonable period of time. (The Army never moves quickly except in emergencies.) Pusan was secure when I arrived, and I do not remember any specific evidences of war. I'm sure there were signs, but I cannot remember them now. My earliest memory of Korea occurred shortly after we landed in Pusan. We disembarked and boarded two and a half ton trucks. About thirty of us were standing in the back of the open vehicle. The stench of Korea, probably coming from the manure used to fertilize the rice fields, was so bad that some of the men leaned over the side of the trucks and threw up. We didn't leave the Pusan Perimeter immediately, and I saw natives all the time. Most clearly is a memory of them driving oxen with buckets of fertilizer that smelled horrifically. I also remember that while we were in Pusan, a number of the men and I were playing softball with North Korean prisoners. The American soldiers left for one reason or another, one at a time. I recall looking up from the game and noticing that I was the only GI left. It was these same prisoners who some time later revolted causing mayhem and death. I was always clear what my assignment was and would be in Korea. I worked in an office similar to "Radar O'Reilly" of the TV program M*A*S*H, except that I was not in charge of the radio. We had a radio man who did that. Initially I was assigned to Service Battery, and later worked in a Headquarters area where solders from all the batteries worked. When it came time to move up to the front, we boarded a ship and landed at Inchon. Because it was a poor port to dock a large ship, we were put on LCM’s (landing craft) and moved up to the beach. At that time, Inchon was in our hands and there was no immediate fighting. We then got on two and a half ton trucks and moved to the Han River. Because the bridge across the river was not accessible, we crossed over to Seoul on pontoons. The bridge had a large gaping hole in its middle. It was a weird sight. When we finally got to Seoul, the capital of South Korea, the city was a bombed-out mess. Machine guns were in the streets, manned and ready to be used if necessary. We did not stay in Seoul at all. It was merely a city that we passed on our way. Remember, we were artillery. There was no place for us in Seoul. We moved into an area where we could set up our big guns. All campsites, as I found out shortly thereafter, were temporary. We moved where our big guns were needed. At the camp, we performed our duties SOP (standard operating procedure). So far as living quarters, most of us were in fourteen-man squad tents. The 1st Sergeant had his own tent, as did our CO. There were also officers' quarters, though I don't remember much about them. I was a non-com with no special privileges. A medium-sized tent was set up for headquarters. We had a section set up as a motor pool, and there was the mess tent--as good a word to describe an eating facility as I have ever heard. Artillery had a different front line from infantry. So far as we were concerned, it was just a campsite where our big guns would go off periodically according to directions from our higher echelon. Other than that, we each did a job that was assigned to us. Cooks cooked, mechanics worked in the motor pool, etc. For the most part, I worked in the office. It was a job most suited to my background. It's hard to say that anything done in a war zone can be classified as something one "likes," but it was probably the least onerous job I could perform. Half the time I was at the front lines (artillery front) with my outfit. The other half of the time I was in the rear where the situation dictated our need to be there. As far as I know, we didn't replace anyone when we arrived in Korea. Artillery was needed and we were sent. No one showed us anything. I was given a job, told what to do, and did it. I knew the basics. The only things different were the day to day occurrences. Most of what one learns comes from experience. One adapts to a situation. We were always mobile. We were basically a detached outfit. Please excuse the vulgarity, but we were called a "bastard" outfit. The term was used for any battalion or other outfit that moved around as it was needed. We were attached at one point or the other to almost every group in Korea. We were with the 24th Division, I Corps, Ninth Corps, 1st Marines, 40th Division, 1st Cavalry, etc. You get the idea. We moved wherever artillery was needed. An Artillery UnitAn artillery battalion was made up of five batteries: A, B, C, Service, and Headquarters. A, B and C were the firing batteries. I don't remember for certain anymore, but I would guess there would have been between 200 and 300 men in the combined batteries. I am not being chauvinistic--there were no women in combat in the Korean War except nurses in the MASH units. The artillery units had what the infantry did not: big guns that had a range of ten miles plus. The infantry did not have howitzers. Wherever heavy fire power was needed, the artillery was called in. Particular to our unit were carbines, 45 pistols, .30 and .50 caliber machine guns (mounted on tripods), bazookas (which had their own base), Howitzers (pulled by half tracks), captured weapons, and grease guns. All enlisted members in our unit carried carbines as side arms. It was only valuable at short distances. More than a hundred feet and they lost accuracy. Officers carried the .45 pistol, except when obtained unofficially (like the .45 I bought). As I recall, there were usually five Howitzers per battery. We had a Chinese burp gun which we had captured. It was a bad weapon because it misfired as often as it worked. The grease gun fired a .30 caliber, I think. I knew very little about guns. I do know that they were not generally worn out. I found the .30 caliber machine gun to be more accurate than the .50 when fired single shot. All other weapons, with the exception of the Chinese burp gun, worked well, so far as I know. If a weapon became unusable, it was replaced. I remember the men in the firing batteries. Two of the men were usually needed to fire the bazookas, which were used against tanks or similar large targets. Howitzers, used when big targets needed to be destroyed, required a group of four to five to man them. Fire direction for the Howitzer was accomplished by a forward observer who could not get insurance. He would radio back coordinates. All of the other weapons were personal weapons that could be fired by line of sight against individual enemies. The men firing the Howitzers were supposed to use a cradle when loading a hundred pound shell into the breach of the howitzer. They usually didn’t bother, instead just shoving the shell in manually. The shells had an O-ring on the front, which was removed, and the firing head screwed into place. Sometimes, the fellows would take a can (a number 10 can, I believe) and cut it open on both sides. They would then slide the can over the head of the shell. When the howitzer was fired, the shell whistled as it flew toward its target. This was meant, I suppose, to make it scary for those on the receiving end. The powder charge that fired the shell was, I believe, an 8-inch charge. On one occasion, the sergeant in charge used a ten-inch charge, whether on purpose or by mistake I never found out. In any event, it was more than the gun could handle and the muzzle blew up, splitting both eardrums of the master sergeant who ordered the charge. Subsequently, he was busted to private. He not only lost his stripes, but his hearing as well. Pincers AttackOn April 21, 1951, we were at the front lines when the Chinese and North Koreans came over the hills. Details regarding the incident are fuzzy in my mind, at best, though I believe we were close to the 38th parallel, if not over it, when it happened. South Korean troops (called ROK) were supposed to prevent their advance, but they turned tail and ran as soon as the enemy pushed down. It was a pincers attack, with soldiers coming down on every side. I'm not a military expert, but a "pincers attack" occurs when an invading force comes down from two sides in an attempt to completely surround their enemy and cut off all means of escape. They had extremely accurate mortar fire, but I believe their battle skill came from their great numbers. On this particular day, the 555th Field Artillery Battalion (commonly called the Triple Nickel) was right in front of us (955th F.A.Bn, my outfit). In what I consider to be an act of bravery, the Triple Nickel put dynamite charges on their Howitzers so the enemy could not get them. They lit the fuses or did whatever they were supposed to do to set the charges off. They then ran toward their vehicles to escape the enemy attack. As they were running, North Korean machine guns cut them down. I was in the back of a two and a half ton truck--the last one to escape the attack without harm. If the men of the 555 had not placed those explosive charges on their guns to prevent the enemy from retrieving them, they might have escaped with their lives. I don't know how the dead and wounded were evacuated. We did not stay there very long after it was over. Our truck moved out as quickly as possible. I assume bodies were retrieved by Graves Registration as soon as it was practicable. I had very little time to think about what had just occurred. I was thankful for being alive. I was busy through the night and the next day, typing out KIA and MIA reports and working with others in tabulating the dead and missing. It was a devastating loss. It was a terrible experience, and aside from what I wrote above, I remember very little else. I know I was frightened (one of the few times I felt that emotion in Korea) when I saw the enemy advancing toward us. It was a horrific event that I rarely ever talk about. I never saw anything before or since as horrid as that event. It almost felt as if I were witnessing this in a movie. To some extent it didn't seem real, though it was real enough. I have had many good things happen to me during my life, but this had to have been close to the worst day ever, only second to the passing of my wife. MASH 8063On another occasion, my outfit was stationed next to MASH 8063. Like the television show, I witnessed helicopters landing with wounded on many occasions, with doctors and nurses rushing to meet the planes. When they were off duty, the doctors and nurses had the wildest parties. Enough said. At one point, we were playing softball. I was in the outfield when a ball was hit over my head. I ran to get it, which brought me into the MASH compound. There was a truck there with its tarp pulled down. For some unexplained reason, I lifted the tarp and saw 1st Cavalry soldiers piled one on top of the other with their dog tags stuck between their teeth, causing them to appear to be grinning. It was a gruesome sight. It was the first time I had ever seen dead Americans since arriving in Korea. There must have been about 20 to 30 dead Americans in the truck. I also saw a dead Korean lying by the side of the road. Remember, we were artillery. Our front line was usually about ten miles behind the actual front. We did not, as a rule, engage in hand to hand fighting. While still in this area, on a quiet Sunday afternoon, a buddy of mine and I (his name was Harry) decided to take a hike (we had permission). I recall that we reached the top of a hill where me met some Belgium soldiers. They invited us to come to their camp and have dinner with them and watch a special services show. We agreed and went to their location. It was quite a hike. Once we were there, we had dinner (I don’t remember what we ate). We were asked if we would like tea or beer as a beverage. I have never been a tea fancier, so I indicated beer. At which time they put the beer in a pot and heated it over a pot bellied stove. At that point, I indicated that I had changed my mind and preferred tea. After dinner, we saw the special services show which feature three South Korean women doing an imitation of the Andrew sisters. They were quite good, in fact. Here are a couple of pictures of that occasion. It was then time to leave and return to our camp. It was rather late and getting dark. We reached a point in the road, and had a problem. Harry said we should go to the left. I thought we should go right. However, I listened to Harry and we went left. Shortly thereafter, we rested a moment and I put my right arm on what looked like a sign. At that moment, a flare lit up the sky, and I could read the sign: it said, "When You Reach this Point You Can Be Observed By the Enemy." My wording may not be exact, but the meaning is the same. About a fifty yards in front of us, I could see North Korean soldiers drawing some sort of map in the sand. I said to Harry, "I don’t know where you’re going, but I’m going to the right." I got out of there, followed by Harry, as fast as my legs could carry me. Shortly thereafter, an American truck picked us up. There were many South Korean civilians in the back who were taken out of caves where they had been hiding. Harry and I called in the coordinates to our outfit, which proceeded to lob shells into that area. Harry and I were both given commendations for this. Another time, we had an organized search of the hills where we believed there were snipers. Most of the time I had a carbine with a bayonet. I bought a civilian 45 for ten dollars that I kept with me. For the most part, I used these weapons for target practice except once. At one point, my buddy, Compitello (don’t remember his first name) and I were held down by a sniper who was firing from behind a large rock. I told my buddy to get out of there and I would cover him while he ran back. I was firing at the rock when the soldier hiding behind it lifted his head. One of my shells hit the rock and bounced off hitting the Korean in the nose. To my knowledge, that was the only human being I ever killed. I didn’t eat for a week after that. The incident had an amusing ending, however, though I didn’t laugh at the time. I strapped my carbine over my shoulder and started to run down the hill. Somewhere along the way, I tripped and went down the hill head over heels. Each time I tumbled, one end of the carbine hit me in the head and the other end hit me in the butt. It wouldn’t have been so bad--I was not really injured--except that I landed in a stream at the bottom of the hill and many of my buddies were standing there and had a laugh at my predicament. Strangely enough, except for those times I have already mentioned, I was emotionally sound without fear while I was in Korea. The fear came when we were caught in the pincers attack on April 21, 1951. I was also frightened sitting in a foxhole while big guns from our ships fired unceasingly. It was the only time I was in a foxhole. There were other incidents throughout the year that I felt fear, but they were only the exceptions. The only war stories I was familiar with before I got to Korea dealt with World War II. They were second hand. Keep in mind that I turned eighteen at the end of WWII. I was more interested in girls than I was in war, though the brutality of war (not of girls) did not escape me. I really had no idea what war was like until I found myself in the middle of it. Take a HikeWe had a particularly stupid CO who did all sorts of idiotic things like camp us in a dried up river bed. My immediate officer was a **** (I do not usually use profanity, but you can fill in the blanks, I'm sure.) He was stupid, nasty, ugly, and those were his assets. Most of the lieutenants were decent, and our first sergeant was as nice as he was stupid. Don't misunderstand me, there were intelligent men in the outfit, but one tends to remember the negative over the positive. On one "memorable" day, Sergeant Delesant, who was not only small in stature, but boasted miniscule gray matter, decided that a group of us should take a hike, a comment I wished to pass back to him, but I was still a corporal and discretion was the better part of a court martial. In any event, we hiked for hours with full pack going well over five miles. Finally, he said we had gone far enough and started back to our camp. This was the occasion for that command heard round the world: "Double Time!" Yea, right. Off he started at a gallop with the rest of the ponies following behind. This maverick, however, continued loping along at minus one mile per hour. He yelled back at me, his voice drifting in the wind, "Court martial for you, Corporal, when we get back to camp." Sure enough, three hours later when I arrived, the papers had been drawn up. I told him that the reason I couldn’t run was because I felt ill. He told me to go to the medics and then he’d make his final decision. This sounded good to me. At that point, I forced myself to begin coughing, doing it all the way to medical facility. When I got there the medic or doctor (I don’t remember which) examined my throat, which had become very red from my forced coughing. He pronounced me ill, and told me that I was restricted to my tent for bed rest until the next day. No court martial, no work--just revenge and delightful rest. On the Firing LineWhile we were camped at this same site, I was involved with two practice firing sessions. During the first one, we lined up and fired at tin cans placed about a hundred and fifty feet to two hundred feet away. I had only my carbine and could not hit the target no matter what I tried to do to compensate. Finally, a GI standing next to me handed me his M-1 and told me to try his weapon. Bang! I hit the target on the first shot. Bottom line: carbines were only good at very short distances. I would not want to have to depend on it if we were ever engaged in combat. The second incident I remember well, but no one believes it. I went shooting with one of our lieutenants. I had my trusty carbine and he had a grease gun (machine gun firing 30 caliber shells). We set up targets, rather close this time, and my record was fairly good. I hit the cans several times. The lieutenant, on the other hand, fired three times and missed all three times. He opened the barrel of his grease gun and found three bullets, each one lodged into the one in front of it. The gun apparently misfired and the bullets stuck into each other. The bottom line: anyone I told this to who had experience with a variety of weapons explained that what I saw could not possibly have occurred. Some thought that I was the butt of the lieutenant’s bizarre joke. I cannot argue that. I only know what I saw. If it were a joke, how did he manage to embed one bullet into another so the three were stuck together? Weather & TerrainIf there is a hell, its name is Korea (with apologies to the Koreans). The summer was unbearably hot and humid with temperatures going well above a hundred degrees. The winters were terrible with twenty below zero not unusual. One season was rainy (fall or spring, I'm not sure which, though I would guess it was fall). It was not particularly cold when I arrived. So far as dealing with the weather, one does the best he can. In the winter I wore several layers of clothes, keeping an extra pair of socks against my body. In the summer, I showered as often as practical under the circumstances, and generally perspired profusely. Because we were not infantry, we did not face the same conditions that foot soldiers faced. We camped in as level an area as possible to make it useful for our big guns. There were lots of hills and often mountains in the distance. For the most part, we didn't personally engage the enemy, though once we were overrun. The only trenches we had were our version of an outhouse. Most were out in the open--a long trench with a pole across the opening on which we sat. Sometimes we actually had a closed-in toilet, but not often. ASCOM CityASCOM City was a bombed-out hospital built by the Japanese, taken over by the South Koreans, and then turned into a headquarters for American soldiers. Before we could occupy the building, we poured gasoline all over and burned out the terrible stench left by the Koreans who had lived there for a time. Two episodes occurred while we were there. The first incident occurred one night when I was walking guard duty on the perimeter of the camp. I had the graveyard shift (midnight till four in the morning). I walked in a straight line from one corner to the next. From time to time, I met the guard who was walking his line, which was 45 degrees from me. Think of it as roughly a square: I walked one line of that square and three other soldiers walked their lines, thus covering the complete perimeter. As I was walking, I heard strange sounds coming from a broken-down shack some hundred feet to my left. It was generally believed that the house was empty. I continued marching back and forth along the perimeter fence for about an hour. Finally, my curiosity got the better of me. I cocked my carbine and stared intently at the building, but was unable to see anything. I slowly approached the building. It was then that I thought I had solved the mystery. I breathed a sigh of relief when I noticed that a door hanging on broken hinges was swinging back and forth on those rusty hinges, creaking like mad. I sighed my relief. For some unexplained reason, I walked into the building. Whack! I was immediately struck on my face and body. I ran screaming from the building, but as I did, I saw that my assailants were bats. The house was filled with them. I took a picture of the "bat house" the next day, and I still have the picture. The second episode occurred after I had been promoted to sergeant (which is a story in itself). Once again, I was on guard duty, but this time as a sergeant. I did not have to walk, but rather stayed in my tent ready in case there was a problem. Well, I guess I dozed a bit when I heard a guard call out, "Sergeant of the Guard, Post Number 8. (I’m not sure of the exact number, but it has very little bearing on the story). When I arrived at the post, the guard had collared a drunk GI in fatigues with no insignia on his uniform. He was obviously American, so I told the guard that I would take care of him. I brought him to EUSAK (Eighth United States Army in Korea) Headquarters and told the soldier there to throw the "guy" into the guardhouse until he sobered up. End of story? Not on your life. The next day I was sitting in my office when a major walked in. He said I was wanted at EUSAK headquarters. When I got there, I was ushered into an office. Behind the desk sat a one star general, head bent down reading some papers. I stood at attention and saluted. When he raised his head I recognized the drunk I had thrown into the guardhouse. He said, "We’ll forget what happened last night, Sergeant." MY only reply was a stammered, "Yes sir." I left as quickly as I could and got back to my outfit. There were two opinions concerning the matter that my buddies offered. On the one hand, they thought he was only pretending to be drunk to make sure the guards were on the ball and doing the job they were supposed to be doing. Obviously, the other point of view was that he was drunk as a hoot owl. I favored the latter point of view. He was so drunk, he could hardly stand up. He also reeked of alcohol. If he were pretending, he deserved the Academy Award. First SergeantFor those of you who do not know what a first sergeant is, he is a master sergeant (three stripes up and three stripes down) who is in charge of the operation of a battery or company. As first sergeant, he has a diamond between the six stripes mentioned above. Our first sergeant was Mel Lamberson, a kind and friendly Neanderthal. Mel’s only redeeming feature was that, with what little gray matter he had between his ears, it was just enough for him to delegate his duties to others more competent. Mel was basically a good person who caused very little concern among his men. He had, however, not a clue about the running of Service Battery. As company clerk (I was a kind of Radar O’Reilly of M*A*S*H), I handled just about all of his paper work. I told him what headquarters wanted him to do, and basically what all the correspondence from higher echelons meant. Given all that I did for him, he approached me one day and asked me what he could do to promote me to sergeant. For me, the answer was simple. My MOS number was 3290 (clerk, typist--MOS means "Military Occupational Specialty). I told him to give me a temporary MOS of 1515 (I believe that number is correct), which was ammo handler, referring to our howitzers. Unfortunately, this meant that I was taking a promotion away from someone who actually worked on the big guns. This did not do much to improve my popularity. Once I got back to my office, I pulled my 201 file (a personnel file containing all the necessary information about an individual soldier). Temporary files were written in pencil. Now that the file was in my care, I changed the temporary designation to permanent (written in ink) and indicated that my position was Headquarters Sergeant in charge of personnel. I did this in the event that after I was separated from the army and I were called back, it would be as personnel sergeant, not as ammo handler or clerk typist. This was insurance for a possible undesirable future. Incidentally, I was also offered another promotion. I was told that I could be given a field promotion to Warrant Officer. I would be given the promotion first and then be discharged as sergeant. It was necessary to do it that way since if they discharged me first, I would be a civilian until I was sworn in as Warrant Officer. I declined the promotion offer since it necessitated my enlisting for three more years. I was college bound and had no idea of making the military my career. Two DevilsOne problem all of us had at ASCOM City was Sergeant Watts (not sure of spelling). He was a real SOB. Nothing ever pleased him. If I wrote a letter, he would re-arrange it without really changing anything. I wasn’t the only one who had a problem with him. Everyone under his command hated him with a passion. Finally, he earned enough points to go home. That’s when we had our revenge. I was the one to write up his transfer orders to go to Inchon and then board a boat, which would take him to a ship that would take him back to California. Unfortunately, I cut the orders incorrectly (deliberately, of course) and I learned later that he went from one base to another, losing an entire month before he finally was on his way home. I then took it on myself to write a letter to him at his home telling him how we all felt about him. We didn’t get mad. We got even. I must add, however, that I was the motivating force in paying Sergeant Watts back for the miserable time he gave all of us. We also had a warrant officer, Lewis C. Perry, who was a pain in the butt. Yelling was his preferred mode of communication, laced with as many nasty comments as his little brain was capable of thinking up. He died, however, in a peculiar manner. He was riding in a jeep when a tank was coming down the road in the opposite lane toward him. The driver, who thought he was at Indianapolis, passed a slow moving vehicle in front of him, only to see the tank bearing down on him. Instead of breaking and getting back behind the slow moving vehicle, he stepped on the gas and zoomed ahead, getting in front of the slow moving vehicle and barely missing hitting the tank. Our "beloved" officer had a heart attack on the spot and died shortly thereafter. Perhaps we were cruel, but no one mourned his passing. Another warrant office, Mr. Dailey replaced him. He was a pip. He told us that he assumed we knew what we were doing and he wouldn’t bother us unless we had a problem. He was true to his word. He went to his room, got drunk, and we never saw him again--at least, not on his feet. Then there was the time I was sitting in my office in ASCOM City when someone came in and said I had a personal call, something that was almost unheard of in Korea. When I picked up the phone, the caller turned out to be my best friend. I had no idea that he had been drafted and that he was in Korea. He suggested that we meet in Seoul at the 5th Air Force headquarters. I asked my CO for a one-day pass, borrowed a jeep, and went to Seoul 5th Air Force headquarters. I spent the day with my friend, Artie. His job placed him on top of a mountain where he and others boosted radio signals to Panmunjom for the peace talks. There were no satellites then to aim a radio signal at. Artie’s job in civilian life dealt with electronics, so he was ideal for this assignment. We ate in the Air Force met. I was amazed at how they lived. Korean waitresses served food to us on real plates, not in mess gear as I was used to. It was a memorable day. HurricaneOur brilliant captain, J.C. Engledow, had us set up camp at the base of a dried-up riverbed. When a hurricane hit Korea, our tents blew away. In an effort to save them, we buried tent pegs in the ground with the lines bound around them. Prior to that, we had used one set of pegs for two tents, effectively connecting all the tents in a row to each other. When the winds came, as one tent went down, they all came down. In addition to burying the poles, we also tied some of the tents to vehicles. It was a wild night. The next day, the rains came. We were camped outside of Pusan when I was asked to go into town to pick up and/or deliver some papers. I don’t exactly remember which. Hours later when I was returning to camp, I found myself walking next to a river which I had not seen before. At one point, I saw an air mattress floating down the river covered with GI equipment. I laughed thinking some poor Joe lost all his belongings. When I looked closer at the items, I realized that all the clothes and other belongings were mine. Later, I had to put in a requisition for new stuff. When I finally got back to camp, all of our big guns were under water. The rain had come down the mountain into the dried-up riverbed where we were camped and turned our camp ground into a rushing river. In order to retrieve the guns, we dynamited the river to change its course. It worked. Captain Engledow finally got the smarts and moved us to higher ground. It was this same rocket scientist who just before Christmas sent us (I was in the rear at the time), the menu for a wonderful dinner we were going to have. The menu had some delicious items on it including "Parker House Steak" and "Porter House Rolls". I brought this to the attention of our Master Sergeant, who said that one does not correct Captain Engledow The menu was then mimeographed and sent to the troops just as he had written it. There was also an incident in the jeep. Again, at the time I was in the rear. Some of my buddies from the front came down to where we were stationed. They wanted to visit some ladies of the evening. I dropped them off at the indicated location and waited for them to complete their current objective. As I was sitting in the jeep with the engine turned off, an MP jeep pulled up along side of me. It contained four men, three of them officers. They inquired why I was just sitting there. For once, I thought fast. I replied in a tired voice: "Sorry, sir, I got sleepy and thought the safest thing for me to do was to rest for a few minutes." The captain replied, "Very commendable. Carry on," as the jeep moved away. Shortly thereafter, the adventurous comrades appeared and I took them back to our quarters. Everyday Life in KoreaBathing was not always possible in Korea. We had shower tents that we used when it was practical. Often we washed in our helmets. I washed in it, cooked in it, and when I was ill, I barfed in it. Clean clothes depended on the season. During the bitter cold winter, we changed less often. In the summer, we changed once or twice a day, conditions (obligations of war) permitting. The food was acceptable. Our cook, fortunately, was a cook in civilian life, so what he prepared (given the rations he had to deal with) was palatable. In the rear, the situation was vastly different. We got novice cooks for a period of time and the food preparation was terrible. Each new cook eventually improved, and when the food got really good, he was shipped to a permanent outfit and the process of training a neophyte began again. I do not recall ever eating native food. The best thing I ever ate in Korea was Thanksgiving and Christmas turkey dinners. I don't know the details of shipping the food to where we were located, but the food was good. I missed the stateside foods of steak and potatoes, shrimp, and lobster the most. Mail was generally good. Most of my letters were from my parents, and many were from girlfriends, but that special girl never wrote. I also received mail from other friends. Packages were all from my mom, and they often contained spaghetti (a favorite food of mine), candy, and other goodies. The Red Cross occasionally sent us packages. I remember some of the humorous things that happened. I once shot a rattler that had come into my tent. He was perched on top of the pole that holds the mosquito net. He scared all of us in the tent, and I killed him with a shot from my carbine. Once, when I was sitting on our outdoor latrine, our laundry lady came over to talk about my laundry. I was very embarrassed. Once, on an outdoor latrine (the long one with a pole across it) a wise guy tossed a match into the latrine, igniting the paper down there. He thought that was very amusing as we all jumped up and ran from the flames and heat. Another time, one of our guys was standing guard duty at a post near the latrine. This occurred about 3:00 a.m. Unfortunately for our Sergeant, this guard was a stutterer. When Sergeant Delesant had the GIs (diarrhea), he ran toward the latrine. The guard started to call out, "Halt! Who goes there?" However, he never got the words out (complicated by fear as well as his normal stuttering). Delesant only heard a mumble, so he cocked his rifle. The guard, hearing a rifle cocked, did the same. The two stood there for almost an hour--each afraid to move. Sergeant Delesant had a lot of washing to do the next day. Needless to say, the stutterer never stood guard duty after that. There were other incidents that occurred almost every day, but they are relatively insignificant and routine. I was a smoker and got cigarettes while I was in Korea. Many times they came as part of a package given to all of us courtesy of the government. I was not a drinker then, and when I got a bottle of liquor, I traded it in for cigarettes as everyone else did. I was not much of a gambler--then or now. When I had leisure time, I went for casual strolls and occasionally played ball with the guys. I also read when I had the chance. I had numerous contact with natives. Some washed my clothes, others worked in our battery. I also had an entire girl's orphanage following me wherever I went. I suppose they were attracted to the food and clothing that I managed to get to them, and I played with them whenever it was practical. They enjoyed that very much, as children would anywhere. The natives lived in squalor, so far as I could judge by comparing their lives with what I knew back home. The children I saw, aside from our houseboys, were those in the orphanage as explained. I'm sure there were the standard prejudices, but I did not see them. The only real prejudice I noticed while I was in Korea concerned two of our boys. One was a homosexual who was treated very badly, and the other was a communist sympathizer. The latter barely got out of there alive. I do not know what eventually happened to him, except that he did not remain in our outfit for very long. Incidentally, I do not remember any black Americans in our outfit that might have exhibited prejudice among the men. Most of us were not political. We were in Korea because our country thought it was important, and there was very little discussion that I am aware of concerning political issues. I did not know anyone that I would call a "war hero." We were all heroes! My strongest memories of Korea are the smells, death, hot, cold, and rain, as well as the food and one or two humorous events. For me personally, the hardest thing about being in Korea was being away from home and generally not being able to do, say, and go where and when I wanted to. R&R in Japan: Part 1

There was no "best day" for me in Korea. Some days were not as bad as others, but the only "best" happened when I got R&R, boarded this C-54, and went to Japan. I had two R&R visits (Rest & Recuperation, though some called it I&I-Intercourse and intoxication) there. I don’t remember the order, though I think the first one I went with my buddy Tony Balsamo. Tony was a very funny guy. He was the kind of fellow who would always land on his feet no matter how serious an occasion would be. In Japan, he was too much. I had a charming companion name Fumiko Makino (Judy for short). At one point she wanted to take me home to meet her mamasan and papasan. I don’t think my parents would have approved, so that ended that. In any event, she was very cute and I enjoyed my time with her. Enough said. Tony’s girl was a real beauty. One day, Judy said she wanted to take me to church and pray for me. I was confused by her term "church," and asked her to explain. She merely said that it was a Japanese Christian church. It turned out to be a Buddhist temple. We took a train into the country and started to climb a mountain that was more of a steep hill than a full-blown mountain. All along the trail up the hill, there were carts on either side selling a variety of merchandise. At one point, Judy insisted that we stop at a fortuneteller’s booth. The man had a box that resembled the one that held pick-up sticks. He shook up the box, handed it to me, and asked me to turn it over. (All this, you understand, was said by gestures. I did not know that much Japanese yet to understand him. I did get some help from Judy, who spoke a little English.) Through a small hole, one chopstick came out. It was covered with writing that contained one’s fortune. The man explained to Judy what my fortune was and she then explained it to me. I do not remember what it said, but I’m sure it was positive. The man would not stay in business long if his fortunetelling were negative. We finally reached the top of the hill. There was a lagoon there with a seated statue of Buddha at one end. I was told that in warm weather, the people would divest themselves of their clothing and jump into the lagoon. This was supposed to have a spiritual cleansing as well as a physical one. Since it was winter, they used a ladle with a long handle that they dipped into the water and tossed on the statue. This was supposed to accomplish the same purpose as a dunk in the lagoon would have. In addition, if they had a pain, they would put some of the water on the affected area. This was supposed to have an ameliorating effect. I won’t tell you where Tony put the water, but I was sure we were about to be mauled by an outraged crowd of Japanese who saw their religious institution being ridiculed. I put my hands over my head in a defensive manner, but to my surprise, the crowd of Japanese was hysterical at Tony’s antics. Nevertheless, I suggested that we leave before we overstayed our welcome. While in Osaka, I met a charming young woman by the name of Kathy Yamaguchi. Unlike the other girls we had met, she would not "fool around." She said she was a "good girl." At the time, she was enrolled in the University of Osaka studying English, among other subjects. Interestingly, she was reading Otto Jesperson’s Philosophy of Grammar, the same text I had been studying at Brooklyn College before I went into the Army. We wrote to each other briefly after I returned to the States. She seemed to be somewhat depressed, perhaps for the state the world was in. In one letter to me she wrote, "No love for me there is." I recently came across that letter. Kathy was very intelligent, albeit, naive, and she was upset by the prostitutes in the hotel in which she was working, She explains that in her letter. The spelling, punctuation, and grammar are all hers, and not bad considering her limited exposure to English.

R&R Part 2I'm not sure how I came to have two R&Rs when most guys didn't even get one. I asked for it and got it. So far as I know, artillery outfits did better in that concern than line soldiers. On my second R&R, everything that could happen, did! An interesting event occurred on my second trip to Osaka, Japan (R&R). I was shopping on the main thoroughfare and came to a store that sold Chinese curios (they also had Japanese items). I walked in and bought several Netzkes (spelling?). These were little ivory figures of wrestlers, a fisherman, an old woman, etc. I understand that they are quite valuable today. That, however, is not the complete story. Apparently, the proprietors were used to seeing GI’s in a rather negative perspective (many were rude and boisterous, I found out). They were so pleased to find an American soldier who acted with respect, that I was invited to join them in a traditional tea ceremony. We went into the back room where we all sat on cushions (not easy for me to do). The table could not have been more than four feet off the floor. I do not remember much about the ceremony, except the tea tasted like warm water with a few grains of tea visible at the bottom of the cup. After my five relatively uneventful days in Osaka, we left Osaka Airport and headed for Korea. Shortly after takeoff, the weather got ugly. I can’t imagine that the pilot didn’t have warning about it, but we took off anyway. It was decided (I learned most of this information after the facts) that we would head south toward Taegu instead of Kimpo airport, where conditions should be better. The pilot intended to land there until the weather improved and then we would continue to Kimpo. Taegu is in a valley completely surrounded by mountains (obvious, but needed to be said). The pilot reduced his engine speed and started coming in for a landing. His windshield, however, was iced over, and in order to see, he had to open a side window. To his amazement, he had overshot the runway. I was sitting in a bucket seat in our C-54 cargo plane. I felt the engine suddenly roar to life and the plane pulled up at what seemed almost vertical. The pilot later explained to me what happened then. He still had his landing gears down and his vertical climb barely missed the mountain. He told me that he couldn’t have put a sheet of paper between his landing gears and the mountain. In any event, we made it or I wouldn’t now be writing this account. He gained altitude trying to get above the storm. In order to make the plane lighter, we were told that we would have to eject all unessential material. The cabin door was opened and what followed was as amusing as it was scary. We tossed items up in the air (we were all buckled in) and they were sucked out. Most of the souvenirs I had picked up in Osaka ended up in the Sea of Japan. It was decided by the pilot and his crew that we would head back to Japan. One option that the crew chief told us was that we could set down in the Sea of Japan. He would then inflate a life raft which contained an emergency radio that would send out a May Day call. All of us would stay in the water holding on to the raft, since it was too small for all of us to get inside it. He also said that in addition to the cold of the water, we also had to worry about sharks. Strange as it may seem, I didn’t feel afraid. It was like watching a movie. Nothing was real. While sitting there, the crew chief came back again to where we were sitting and asked if any of us would like to see how a plane was flown. Several of us accepted his offer. When it came my turn, I entered the cockpit and the sight I saw was startling, to say the least. Understand that I knew next to nothing about how a plane operated. In the front of the cockpit, normally the place were the pilot and the co-pilot sat, were two empty chairs. The steering wheels were moving back and forth like ghosts were at the helm. The captain explained that in severe weather, the automatic pilot held the plane more level than a human could. In any event, the pilot, co-pilot, and radioman were playing pinochle. The only crewmember working was the navigator who was doing his thing with charts in front of him. Finally, we were told that we were coming in for a landing at Atami airport. When we landed, I was walking with the pilot (he looked like the actor Sonny Tufts, about six feet six, with his cap at an awkward angle) toward the terminal. I asked him how much gas we had left. He said about fifty gallons in the wings. I sighed a sense of relief, and said thank goodness for that. He laughed and said that was about ten minutes flying time and the next airport was twenty minutes away. If for some reason Atami airport were closed, we would have been in big trouble. New Year’s EveThe next day, the weather cooperated and we flew back to Korea and landed without incident. My headaches, however, were not over. When I got back to camp, I had been listed as AWOL and court martial papers had been drawn up. It took a bit of explaining and a phone call to Eighth Air Force to confirm my story. The event still had more to come. I got home on New Year’s Eve. Just about everyone in the camp was blotto—soused to the gills. I walked into Sergeant Delesant’s tent and he offered me a drink. At that time, I was close to being a tea totaler, not from any moral reason--I just did not drink very often. The liquor that he gave me was rough to my taste and I reached for a can of lemonade that stood on a table near me. He yelled at me not to drink it. "Cheap bastard," I thought, and gulped it all down. Yeow! I never tasted anything like that! I quickly grabbed the bottle of liquor to kill the taste of lemonade which turned out to be lemon concentrate needing water to make it palatable. In any event, this was a night I will never forget. All good things must come to an end. Shortly thereafter, I was told that I had earned enough points to go home. That’s another story. I ended up on a merchant ship heading to San Francisco. I was at the front at that time, and our houseboy, Pakee (spelling?) cried as my truck left the compound with me sitting in the back waving at him. I suppose he had good reason for liking me. Aside from the food, money, and clothes I managed to get for him, I had saved his life. PakeeWe had pot belly stoves for warmth and a little cooking. We were supposed to use oil in them, but oil was slow and dirty. Many of our stoves, therefore, ran on gasoline—much more efficient and much more dangerous. Kim (pictured) and Pakee (also pictured) were our two houseboys. One of Pakee’s duties was to clean out our tents and clean the stoves. On one occasion, he lifted the lid from the stove, unaware that it had not been turned off as it should have been. When the heat hit him in the face, he backed off quickly, in the process banging into the pipes that connected the gasoline to the stove. Gas poured out, hitting the stove and flaring up all over Pakee. He ran out of the tent screaming. At that point I was passing by and saw him in flames. I grabbed a woolen blanket (don’t remember where I got it), wrapped Pakee in it, and rolled him on the ground. His wounds were superficial (I caught him so quickly that he only got minor burns). Needless to say, so far as Pakee was concerned, I was just promoted to God. There was also an orphanage of little girls near our camp. They ranged in age from about three or four years old to about eleven or twelve. I often gave them food and goodies (candy bars, gum, etc.) and clothes as I was able to obtain them. I played games with the children when I had the time and they became my shadow. Wherever I went, they were sure to follow me. I never recalled seeing an adult in charge of them, though there must have been one. |

|||||||||||||||||