|

We need your help to keep the KWE online. This website

runs on outdated technology. We need to migrate this website to a modern

platform, which also will be easier to navigate and maintain. If you value this resource and want to honor our veterans by keeping their stories online

in the future, please donate now.

For more information, click here.

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| Back to "Memoirs" Index page | |||||||||||||||

|

|

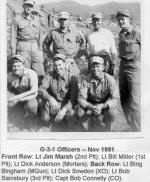

Carleton D. "Bing" BinghamGardnerville, NV- "My return from Korea made me aware of the responsibilities that the United States had undertaken--a protector against the spread of communism. I gained a respect for the men and women in the armed forces in what they were training to be prepared to do. If the United States hadn't gone into Korea, I believe that more than just Korea would have succumbed to communism." - Carleton Bingham |

||||||||||||||

Memoir Contents:Pre-MilitaryMy name is Carleton D. Bingham. I was born March 25, 1929 in Washington, D.C., a son of Carleton Rudd and Dorothy Dille Bingham. I have one brother, living in San Diego, who is three years younger than I. My father initially was a US Postal carrier in Washington, D.C. He and my mother divorced in the 1930s and he went to California where my grandfather had retired. My father worked at the Ft. Rosecrans National Cemetery, where he later was Assistant Superintendent prior to his death in 1949. After her divorce, my mother worked for the FBI (details unknown, although I have an autographed picture of J. Edgar Hoover). She later came to California and worked as a hotel greeter (desk clerk) in San Diego and later in Beverly Hills, then La Jolla, from which she retired. My brother and I traveled from Washington D.C. (where I attended several elementary schools) to California in 1936. I attended elementary school at Ocean Beach School in San Diego, California. After graduation, I attended Point Loma High School (then a 6-year school) in San Diego. I worked as a cleanup person at a local drug store in Ocean Beach. I went to Los Angeles briefly during the 8th through 9th grades, attending Berendo Junior High School. While in Junior High School, I had a magazine route delivering the Saturday Evening Post, and later a paper route with morning deliveries of the Los Angeles Examiner. At age 12 (then the earliest age for membership in the Boy Scouts), I joined Troop 28 in Ocean Beach and when I moved to the Los Angeles area, Troop 2. As a scout in Troop 28, where my father was serving as a scoutmaster, we made many bicycle hikes to local camping areas--some as far away as 25 miles. At age 14 in Troop 2, I earned the rank of Eagle Scout and was initiated into the Order of the Arrow. In Troop 2, the Junior Assistant Scoutmaster, whom I "rescued" while qualifying for the Life Saving Merit Badge, was John Erlichman, who later was President Nixon's advisor. I served as a winter and summer staff member at Camp Josepho in the Santa Monica Mountains. One of the Camp Josepho staff members was Alden Barber, who later was to become the Chief Scout Executive of the Boy Scouts of America, headquartered in New Brunswick, New Jersey, and whom I was to see again in 1971. When I returned to Troop 28, I served as Senior Patrol Leader, then Junior Assistant Scoutmaster. The Boy Scout experiences taught me the beginnings of leadership and how to cope with nature and wilderness situations. I was in school during World War II. My father had served in the Army in France during World War I, but none of my family was in World War II. I don't recall any special activities in which the whole school or individuals participated as part of the war effort, but while in Junior High School I was an Air Raid Messenger in the Los Angeles, California area. I volunteered for the job. An Air Raid Messenger was part of the Civil Defense Program during World War II. A messenger was an assistant to an Air Raid Warden and carried messages from the Warden to a local headquarters. The neighborhood teams only functioned during air raid drills and helped enforce "blackouts"--i.e., assuring that lights from residences could not be seen from outside a residence. I don't remember any alerts that were based on real alarms; drills were something that practiced blackout adherence. I returned to Point Loma High School to begin my 10th grade and from which I graduated in 1946 a few months after my 17th birthday. I lettered two years in baseball and basketball, and was Student Body President and class Valedictorian. During the summers of my junior and senior years in high school, I worked for the US Forestry Service as a crewman in the Blister Rust Control Program at forests in Kings Canyon (Junior) and Yosemite (Senior) National Parks. While in high school, I had considered seeking an appointment at the US Naval Academy and, although I had taken my exams, I decided against seeking a military career at Annapolis. Competition for Congressional appointments to the Service Academies was extremely intense. I could not be certain of acquiring a timely college education through an appointment to Annapolis. I had taken the qualifying examinations during the first semester of my senior year in high school. Trigonometry was given in the second semester and I had not prepared well enough to pass that portion of the examination for entrance in September of 1946. I was accepted at San Diego State College (SDSC--now SD State University) and matriculated beginning in 1946 along with thousands of World War II veterans. Platoon Leaders ClassI joined the inactive reserves in 1947 in an attempt to assist in educational expenses since my family was not able to afford to pay my college expenses. I transferred in 1948 to the Marine Corps Reserve/Platoon Leaders Class (PLC)--a program which, if successfully completed through two summer six-week periods of intensive competitive training, would commission me a Marine Second Lieutenant upon my college graduation. San Diego, being a large military town during World War II, had given me a near first-hand view of the military. I was impressed with the personal stature--and the uniform--of Marines over the other services. That was my primary incentive in selecting the US Marine Corps. My parents were supportive of my choice. I wasn't aware at the time of other students at SDSC who had signed up for the PLC program. I did not attend a "boot camp" like other enlisted Marines did. The PLC summer sessions at Quantico, Virginia, were designed to test the physical, mental, emotional, and leadership capacities of the officer candidates and to weed out those that "couldn't hack it." I drove to Quantico from San Diego that first summer (1948) with two college friends--Ernie Agee and Warren Brown--and returned by train. I don't remember how I traveled from San Diego to Quantico in 1949. Since I did not attend a boot camp, I'll equate PLC summer training with the boot camp that others experienced. The PLC Program was conducted during the summers at Marine Corps School, Quantico, Virginia--about 30 miles south of Washington, DC. Although the main area of the base is highly built up, there are many outlying field and forest areas in which to conduct field training. Summers in Virginia are typically warm and humid--conditions that tax an individual's physical endurance. Mosquitoes and ticks were abundant--also taxing an individual's physical and emotional being. I don't recall snakes or other animals, but I'm sure they were present. Upon arrival at Quantico, each of the candidates was signed in and assigned and bussed to a barracks and told to make up a bunk (upper or lower), police the barracks and stow one's "civilian gear." I don't remember other first day experiences. The "DIs" were all Staff Sergeants, Sergeants, and Corporals, and presumably World War II vets--I wasn't then cognizant of the meaning of ribbons that were worn. The senior DI was not at all enamored with "college kids" and made that very clear from the start. His approach was part of the "weed out process." Each PLC session was six weeks long. Instruction consisted of physical exercise, close order drill and the manual of arms, classroom instruction, and field problems. Classroom instruction consisted of military (Marine) history, small unit tactics and leadership. Fieldwork included weapon marksmanship and weapon maintenance, small unit tactics, and leadership. I don't recall any specific qualification/proficiency tests, aside from weapons marksmanship. Except for the pistol (I thought I could throw it more accurately), I shot "expert" in all other weapons. Days were highly regimented--reveille was 0600 (I think) with a bugle call. Candidates were to shave, bunks were to be made, and barracks were to be policed before morning muster formation in a designated uniform and a march to mess hall. Mealtime was short. Food was plentiful, but you ate what you took. It was high caloric. I don't recall any specific standout entrees, however powdered eggs were not high on one's list of favorites. After marching back to the barracks, candidates fell out for classroom or field with designated field/classroom equipment. One was expected to shower after returning from the field or before lights out and shave in the morning before formation. [I learned early on that hot showers were for the early arrivals at the barracks from the truck drop-off after field operations–-a half mile from the barracks that, with rifle and full pack, I could run and get a hot shower.] Training was constant--whether fieldwork, classroom, or close-order drill. If the barracks didn't pass morning inspection, it had to be policed after evening chow. Lights out was 2200 (I think). I don't remember being awakened in the middle of the night--we might have been. Church was offered and, because church had always played an important part of my life, I probably attended as regularly as I could, although I have no remembrances. I don't recall the obvious presence of our DI corps at chapel. Free time seemed to be at a minimum during the work week. On weekends, one could exercise in the gym or play pickup games of basketball or volleyball. "Fun" was in competing against other individuals or teams, whether it was during the formal training during the week or in weekend pickup games. I've always enjoyed the challenge of competition and I never regretted signing up for the PLC Program and the Marine Corps. The DIs were strict--their words were law. You obeyed their orders or were faced with being removed from the PLC program. I don't remember any corporal punishment, except running laps with one's rifle held above one's head as a "reward" for screwing up. I don't recall being personally disciplined for screwing up. Personal discipline to others was a result of messing up close order drill or manuals of arms or for not being on time for various formations, although I don't recall any specific person as a troublemaker or "screw-up." The penalty could have been running laps, or specific barracks cleanup tasks. Where an individual's wrongdoing impacted upon a team's performance--in a field problem, for example--an entire team might have been disciplined as an incentive to perform as a team, not as individuals. Small unit performance, and hence success, is dependent upon each person doing his task properly, hence "all for one" discipline. At the time, I wasn't aware of any individuals that had been asked not to return to the second PLC summer. However, low field and classroom performance was the primary reason for not being allowed to remain in the program. I don't recall that there was a ceremony at the end of each of the PLC summer sessions. Aside from a feeling of personal satisfaction in having successfully competed and completed the program, I did not have a strong feeling yet of being a Marine. This is probably because there was no follow-on of Marine-related activities--just back home to San Diego to school and work. After completing the program, I had a higher feeling of self-satisfaction and in my ability to compete in life's challenges, but I had not yet begun an organized participation in a Reserve activity. I think I returned home by train from Quantico to San Diego. War Breaks OutFor the remainder of the summer after PLC, I had two part-time jobs--one at the San Diego State College Chem Lab as a Lab Assistant, and the other at a soda works bottling plant until school started in September 1949. During my senior year at SDSC, I was active with my fraternity both as an officer and with intramural sports, held a part-time job at the soda works, and sang in the church choir where my girlfriend of three years (Betty) played the piano. I graduated in June 1950 (just before North Korea invaded South Korea) with a Bachelor's degree with Honors and with Distinction in Chemistry, and was commissioned at the commencement services as a 2nd Lieutenant in the US Marine Corps. I had planned to be a high school science teacher, so I had another year to obtain a teaching credential and a Masters degree. During the summer of 1950, I worked in the chem lab and at the soda works and was responsible for maintenance at an apartment house owned by a friend. Betty and I married in August and after the honeymoon she began rehearsals for a musical at a community playhouse that had a subsequent long run almost until I left for active duty. When the Korean War broke out, I knew where Korea was from high school geography, but knew nothing of the North-South politics. The early reports of how the war was going understated the North Korean capabilities and overstated the US and UN strengths. Based on this misinformation, I wasn't certain that I would be called because I was still enrolled in an academic program at SDSC. I don't recall my feelings at the time. I knew that I had incurred an obligation to the Marine Corps, but I wanted to finish my academic work first, and so requested when I received orders to active duty. However, that request was denied. The depth of coverage of the war by the news media then was nowhere near what it is now, consequently there were few details. But it was clear that the UN forces were being clobbered by the North Korean forces. I had no television, so I relied upon radio news and what was in the newspaper. As to my family's reaction to the news that I was being activated, my father had died the previous year, my mother understood my reaction, and my wife was understandably concerned. Many of my fraternity brothers were World War II vets--they understood and were supportive. Many of my high school classmates were unaware until later that I had been called to duty. I had no pre-conceived attitude regarding the relative strengths of the armed forces of either side, but as things began to unfold, it seemed clear that the US/UN forces initially were not getting the job done. I did not realize the complexity of the Reservoir campaign and that the situation was so dire. Maybe I was not paying enough attention to the news. The first year of graduate school and a wife and two jobs took a lot of time away from reading the news or listening to the radio. TBSI was not part of a reserve unit when called to active duty. I was assigned initially to the Basic officers school in March of 1951. While I was at TBS, Betty remained at home in San Diego where she had a job in a music store and continued her activities in little theatre. At Quantico, I lived in permanent barracks with wall-to-wall double racks. I don't remember how many men were in each building. The Basic Officer's Course was regularly a 9-month course, but our 4th Special Basic Course (SBC) was 12 weeks. Obviously some subject areas suffered. The intensity of scheduled activities demanded a high level of attention over many hours of the day and night. Weekends were typically free time, but off-base liberty was not always granted. My aunt and uncle lived in Washington DC, so when I was able to get liberty, I visited with them. There were several instructors at TBS that I remember well. I recently received a roster and recognized other names as well. Not all of the roster-listed instructors were assigned to our TBS unit. Captain (later Major) "Ike" Fenton came to TBS after the Chosin Reservoir campaign and was our best-known instructor. I later found out that George Westover, the George Company CO during the Inchon campaign, was an instructor in the other TBS unit. Captain (later Major) Joe Loprete was one of the more colorful instructors that kept lectures from being sleep inducers. Others were Captains Jim Apffel, Richard Kuhn, and Richard Sengewald. At the time I wasn't aware of the military qualifications of any of the instructors; however, they all presented lectures in a very professional manner--no "er's" or "ah's", etc. I later found that Fenton and Westover had been selected by their respective Regimental Commanders in Korea for assignment to TBS. Colonel (later General/Commandant) David Shoup, who earned the Medal of Honor in World War II, was the director of TBS at the time I attended. Small unit tactics were taught by the lecture, demonstration, application (LDA) mode. We were shown what to do both in formal classes and in the field, then expected to perform them in the field. We were expected to qualify as Marksman, Sharpshooter or Expert in the marksmanship in the pistol, rifle, carbine, and automatic rifle. I fired Expert in all but the pistol (Marksman). We were required to be able to care for and clean (disassemble and reassemble) all of the mentioned weapons. We were exposed to grenades, machine guns, and mortars. School Troops were "aggressor forces" against which student units exercised the various aspects of our training. Supporting arms was primarily a lecture subject, but normally was taught at later schools. Individual students were assigned daily to leadership positions within squads and platoon. These were exercised both in the classroom and in the field. I don't recall specific courses on deportment and behavior. I'm sure there must have been some, but we were expected to study an Officer's Handbook. Military history and law, and the customs and traditions of the Marine Corps were courses that were presented as lectures. I can't recall specific training in radio-telephone communications, but there must have been some. Proper uniform was emphasized via instruction and daily inspections by student leaders and by School NCOs (DIs). Improperly worn uniforms "earned" demerits which adversely impacted class standing. Discipline was addressed by School officers and NCO's, although I can't recall specific problems. Non-attention in class resulted in demerits which also impacted class standing. Emphasis on esprit de corps began with "God, Country and Corps", followed by constant reference to team work and responsibility in carrying out tactical assignments. I don't recall essay assignments, per se, but there were examinations that required essay answers rather than solely multiple choices. Physical conditioning played an important part of a student's life. Training consisted of daily calisthenics and marches (both in formation and in the field). Weekends frequently involved voluntary participation in pickup basketball or volleyball games. Inasmuch as I had been active in intramural athletics in college, I was in pretty good physical shape, which was a big help at TBS. Upon graduation from TBS, I was assigned an infantry military occupational specialty (MOS) and directed to report for assignment to the 13th Replacement Draft at Camp Pendleton. Training consisted of repetitive small unit (fire team, squad, and platoon) operations, small arms (rifle, carbine, pistol, and BAR) qualification, and map reading, and concluded with a "Three-Day War" in which company-size units made an amphibious landing onto the California coast and proceeded to advance up the valley (at Camp Pendleton) against "aggressor forces" to take a predefined piece of ground. Trip to KoreaSince I could no longer maintain the apartment house, I needed to find a house for my wife before I left for overseas assignment in Korea. My wife and her family were understandably concerned, but supportive. My mother and brother likewise were concerned, but supportive. My wife, not mother or brother, took me back to Camp Pendleton for the goodbye before shipping out the next day. I left San Diego for Korea as part of the 13th Replacement Draft in September of 1951 on the troop ship General Meigs. I don't recall the tonnage, but the ship had been used in World War II. Everything was gray and very much confined. Enlisted quarters consisted of rows of hammock-like bunks--four deep. Officers' quarters consisted of rooms with two or three stacks of four beds, i.e., eight or twelve men to a room. I don't know the troop capacity--there must have been at least the equivalent of a battalion--about 1000 men--maybe more. There were only Marines on board except for the crew. There must have been cargo as well as personal baggage, however, I don't recall cargo being loaded or unloaded. I had never been on a large ship before--only on an off-shore fishing boat with my grandfather. The sea off the coast of California is typically rough and many did get seasick, however, I didn't. The ship's motion, coupled with the "close air" below decks, contributed greatly to the discomfort of the troops. Aside from the coastal swells, the remainder of the trip, as I recall, was fairly smooth. The trip took more than a week--maybe ten days--to get to Kobe, Japan. There was sunbathing on the upper deck. Several attempts were made to show the movie "Jim Thorpe, All-American", starring Burt Lancaster. However, each night there was difficulty with the projector. We never saw it in its entirety. Officer duties included inspections of troop quarters and the troop mess lines. There were no eventful happenings that I recall. Those men and officers that I had trained with at Camp Pendleton were the only persons that I knew aboard ship. There were other officers that I met during the course of the trip. Lts. Roger Barnard, "Champ" Fisher, and Doug Murphy are names that come to mind. I have some photographs of people, but can no longer put names with most of them. The troop ship went directly from San Diego to Kobe. There was supposed to be liberty in Japan before loading for Korea. However, it didn't happen. We offloaded from the Meigs and across the dock, boarded a smaller ship whose name I don't recall, and headed for the east coast of Korea, passing through a strait nearby to Hiroshima, where the first atomic bomb had been dropped during World War II. New to KoreaWe arrived in Korea in early October 1951. There was no port as such. We were to make an unopposed amphibious landing near a town sounding like Socho-ri (I've looked on maps, but can't find anything close). I believe we were north of the 38th parallel, but I've never been able to locate on a map where we landed. As soon as we arrived, we offloaded down the nets to landing crafts late morning or early afternoon. Aside from the hilliness, I don't remember any major first impressions of Korea. Other than the amphibious landing onto a strange land, there were no sights or sounds that told us we were in a war zone. However, being issued live ammunition for rifles, carbines, etc., was a clear indication that it was no longer training. I was armed with an M-1 carbine (a 30 caliber semi-automatic small "rifle"). At the time of our arrival, I had no detailed information of my assignment, except that it was to be to an infantry unit. Advance assignments may have been made prior to our arrival. From our landing place, we were trucked to what we were told was 3rd Battalion First Marines Headquarters, arriving in the dark of night. During the trip from the beach to Battalion, I don't remember seeing any native Koreans. There were natives assigned to each Company/Battalion to serve as cargo carriers. They carried amazing loads of rations, wire and ammunition up the hills from the supply point to the line companies. After arriving at Battalion, we were told to “sack out.” We rolled out sleeping bags on whatever flat ground we could find in the dark--not knowing that we were near a 105mm artillery battery of the 11th Marines that was firing harassing fire all night long onto enemy positions. It was not until the next day that I joined "George" Company, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division (Reinforced), where I was assigned as Platoon Leader of the Machine Gun platoon. I was one of five replacement officers assigned to George Company. I don't recall a hill number for our location, but there were some, like Hill 854, etc. The 1st (I think) and 3rd Battalions of the 1st Marines were on line, improving defensive positions on the forward and reverse slopes of a hill line looking north toward the enemy. We were also to carry out infrequent patrols with the goal of taking prisoners for intelligence-gathering purposes. Upon arrival at the George Company CP, I was aware that there were no officers or men that I had known in the replacement draft assigned with me to George Company (G-3-1). The only two officers in the Company when I arrived were the CO Commander, Lt. Bob Connelly from Southern California, and the 2nd Platoon Commander, Lt. Jim Marsh, an Annapolis graduate and the only Regular officer in the Company. I didn't know until later that Jim had majored in Chemistry at the Academy. Jim had a battle-earned reputation of being fearless under fire and that his men would follow him "to Hell and back." He is remembered to this day as a strong, fearless leader who instilled strength and courage into his men. When Jim was rotated home, I was honored to be the Commander of his 2nd Platoon. When Lt/Capt. Connelly's rotation time came, he was replaced by Capt. Fred Kraus. Kraus seemed to be nervous while on line, but he was jovial in his disposition. He spent a lot of time in his bunker and didn't make contacts with the men on line. I think he had been in public relations. He didn't seem to have much experience from which to command an infantry company of Marines. As mentioned, my first duty with G-3-1 was Platoon Leader of the Machine Gun Platoon. (There are three rifle platoons, one MG platoon, and a mortar section in each rifle company.) From the crest of the hill that we occupied, we could see across the valley to enemy positions on the next hill line north of our positions. During the climb up the hill the first morning before reporting to George Company, there were enemy bodies that had not been recovered or buried. I don't think I had any feeling of remorse. I did notice how poorly they were clothed--no boots, but something like tennis shoes. I don't remember seeing a dead Marine while on line, although there were some killed in action. There were some men wounded while on patrol whose wounds didn't look severe (e.g., small holes, not blown off limbs), but enough to require evacuation. I was saddened that I hadn't known the wounded men, but was relieved that I was not the one that had to write letters to relatives. The individual MG sections of the platoon were assigned to each rifle platoon of the company. As such, I had no people initially to command. For that reason, I initially felt unused, but it gave me an opportunity to observe things without having to assume some responsibility. The first few days involved improving bunkers, trenches, foxholes, protective barbed wire, and lines of phone communication from the Company CP to platoons, squads, fire teams and individual Marines. There were random rounds of incoming artillery and mortar fire and random outgoing artillery fire over our heads, each more annoying than damaging. There was no small arms fire between the two lines. Although we could see individual enemies across the valley on the next ridgeline, we couldn't see them "up close." Other than their nighttime wire probes that required exceptional stealth--especially when there was crusty snow on the ground--I couldn't attest to their fighting quality. Tied into the battalion's flank were Korean Marines. I was told that they were good fighters, but I had no opportunity to observe that. At night they had the annoying habit of coming into the platoon area, scrounging for whatever they could get. I/we couldn't tell the difference between a North Korean and a South Korean, so there was always an uneasiness about their presence. Other than contact with Korean Marines, I had no contact with South Korean military. We had some contact with South Korean civilians. South Korean laborers carried rations, ammunition and wire (in amazing loads) up the hill to our positions on a near-daily basis. Many we grew to recognize and call by name. There was a story about a laborer who was caught sending detailed location information to the enemy to use in artillery/mortar attacks, but I couldn't verify the story. I'm sure I was concerned if/when I became involved in a firefight of a combat patrol. However, there was consolation that most of the men had already seen battle and the NCOs "helped out" green officers by offering sound advice for given situations. The enlisted men told me of how the enemy typically attempted to approach the protective wire at night to leave propaganda leaflets or toss grenades. Other information given by NCOs included individual experiences and on whom one could count in a firefight. Not learned in Basic School, but learned very quickly in Korea, was how to differentiate the sound difference between outgoing and incoming rounds, the characteristics of a "burp gun", how to effectively emplace protective wire, etc. It was early autumn when I arrived in Korea. The weather was not unpleasant, although somewhat humid as I recall. There were some periods of rain, although I had no trouble with the weather. The terrain was a series of generally east-west mountain ridge lines separated by valleys. There was little vegetation to be used as concealment. One slept in bunkers (holes in the ground covered with logs and dirt for protection from mortar and artillery fire). There were also foxholes (fighting holes) connected by trench lines. Fire support was received from artillery, 4.5 inch rockets, 81mm and 4.2 inch mortars, and, in one instance, 16-inch naval guns from the battleship New Jersey, lying offshore. When the USS New Jersey fired into enemy positions in front of our lines that morning, it was an awesome experience! Although Marine close-air support had been available earlier in the war, now it had to be requested from Air Force Headquarters a day in advance--not much help when we really needed it. During my tour we had no tank support that I can recall. Jim Marsh went to tanks after leaving G-3-1. I was never involved in a hand-to-hand situation while in Korea, but my first exposure to fire came in December 1951. The enemy apparently was stealthily probing our wire at night for all weaknesses. Our phone line communication within the platoon had gone out and I was following the wire looking for broken/cut lines and checking each "watch post" and its occupants when some grenades came from the direction of the wire. A grenade fragment made a slight cut on my right lower leg that only required a "band aid." Grenade fire was returned, but no penetration of our lines occurred. Each post continued its watch the remainder of the night. When G-3-1 was online, there were no major assaults on either side. Most of the efforts involved squad/platoon patrols primarily to take prisoners for intelligence gathering. Patrols were both daylight and nighttime on our side. The nighttime ones usually were larger in force. The enemy did not attempt daylight attacks while I was there--only nighttime probes. Again, the enemy appeared to be more skilled in stealth operations. We hardly ever heard their approach to our wire. On the other hand, our approach could almost always be heard. There were always "night watches" in each fighting hole, whereby one of a pair slept while the other watched, and vice-versa. On a predefined frequency, each watch called into the Company Headquarters over a phone line. Wire was out front, frequently with ration cans with stones hung on to it to provide an audible alarm if the wire was disturbed. Enemy infantry probes carried "burp guns" (a small automatic weapon) or rifles. Enemy artillery and mortar fire was always evident. It was VERY accurate! When on the receiving end of mortar and artillery in early 1952, there was a concern that our defensive positions could not withstand the bombardment. Life in G-3-1My bunker, built by Koreans, was about a four-foot hole dug into the ground on the reverse slope of the hill. It was primarily for sleeping. The top was covered with about two feet of logs and dirt to provide potential protection against artillery or mortar fire. It was never tested. Under the dirt floor, some small trenches carried hot air from an external heat source to heat the bunker floor (radiant heat). The entrance did not allow direct access into the bunker. Rain did not get in, and I never saw any non-human inhabitants in the bunker. A foxhole was different than a bunker in that it was either a temporary sleeping hole or a fighting hole, typically on the forward slope of a hill. Trench lines connected several foxholes. Foxholes allowed observation to the front toward the enemy. None in our company was harmed by a Korean civilian or taken prisoner of war during my time with G-3-1. I'm sure all of us had some concern about being captured, but I don't recall any specific discussion about the subject. There were casualties in G-3-1, however, I had no close friends or buddies killed in Korea. Carl Winterwerp, a machine gunner from the 13th draft who is now living in Maryland, was wounded in a patrol action. There were others wounded (maybe even killed) whose names I don't recall. Before I arrived, one of a set of twins allegedly was playing "Russian roulette" with a pistol and killed himself. On another occasion, before I came to the 2nd platoon, because an earlier squad-sized patrol had surprised some enemy, Battalion Operations reasoned that a larger force would be more effective and sent Jim Marsh's 2nd platoon over the same terrain. The enemy was waiting and a heavy firefight ensued, resulting in a number of wounded Marines. I always felt that Battalion Operations erred in judgment by covering the same terrain in too short a time interval. "Gus" Mork was the senior Navy corpsman in G Company who took care of our casualties. He was thorough and capable and he brought some comic relief with his dry humor. When he returned from Korea, Gus went to Med School and stayed in the Navy as an M.D. He retired as a Captain (O-6). I talked to him on several occasions in the past four years, trying to get him to come to one of the G-3-1 reunions. He never made it to one. He died in October 2000. He told me that he had served with all branches of the service during his career, but he most cherished his experiences with the Marines. Personal hygiene was emphasized as a precaution against disease. However, with limited water on line, it wasn't easy. Brushing teeth and washing faces was the limit. Shaving was encouraged, but not enforced. One carried in one's pack extra underwear and socks (I can't remember extra utilities) that were changed frequently (weekly). Washing them except in rain or snow was something else. It wasn't until we went into reserve that we had showers and an issue of clean clothes. Food on line consisted exclusively of "C-rations." Some were better than others when eaten hot. Most "heavies" weren't very good cold. In reserve we had hot food prepared in field messes. Breakfast was powdered eggs or cheese, potato salad, coffee, fruit ade, milk, etc. Dinner might be meat, mashed or boiled potatoes, vegetable, bread, coffee, milk, dessert (pudding or cake, etc.). I never ate the native food. There were too many horror stories about it. The best thing I ever ate in Korea was at Christmas. It was a fruitcake soaked in rum from home. I missed milk and fresh fruit and vegetables the most. I did not drink before going to Korea. While on line there was a beer ration of two cans per day. Since beer was delivered with rations but water had to be re-supplied by individuals from a water point at the bottom of the hill, it was easier and safer to drink beer--not as a past-time, but with a meal. What I didn't drink, I traded for more desirable heavy C rations. I didn't smoke, so I traded the cigarettes that came with C rations [Lucky Strike “greens” from early World War II] for haircuts, rations, etc. Occasionally when G-3-1 relocated, I saw some of those that I knew from the 13th Draft, but they had gone to other organizations in the Division. GySgt. Hank Schram was my machine gun platoon sergeant, and he and I spent a lot of time together while we were in Korea. He taught me to play cribbage. He went home before I did, but we've kept in touch through the years. I also remember some of the 2nd platoon men who were "characters" that kept others of us laughing. "Rebel" was one of them. Once when a "short round" of white phosphorus landed near our position, some ran around looking for a burn that would get them evacuated. None were successful, but it was funny to watch. Regular mail came from my wife and family. Reading material and candy/cookies were welcome treats from the mail. I wrote home and asked for them to keep the paperbacks coming. I think I read all the Perry Masons that were ever written. As I recall, most of the mail arrived okay. I read a lot and wrote letters in my free time. From the autumn weather in October 1951, which was not unpleasant, it began to get colder in early November and turned frigid in December and January. During November 1951, the 3rd Battalion went into "Regimental Reserve"--a "Tent City" in a rear area--for rest, training, showers, and hot food. Then we went back on line around Thanksgiving at a different place of the same main ridgeline--this time closer to the enemy. The cold affected us in many different ways. With regards to our weapons, it was essential when cleaning a weapon (rifle/carbine) in cold weather that one did not apply too much "lubriplate" to moving surfaces because it thickened in the cold, causing the weapon to be sluggish. In the summer, our uniform was the light green utilities, augmented by a field jacket. But to cope with winter temperatures, from skivvies and a T-shirt one added long underwear tops and bottoms. Above that were wool pants and a wool shirt. On top of the shirt was a wool sweater, then a field jacket and/or a long parka. A wool scarf made into a mask that protected one's face, and an ear-flapped cap covered the head. Thermal boots replaced regular boots later in the winter. They were much better for keeping feet warm. On patrol, the long parka was too much--one worked up a sweat. But one needed it if we were on outpost. In winter, the enemy had a "quilted" jacket and pants, but no adequate footwear. I spent Thanksgiving and Christmas of 1951 on line. Special hot meals were served, but there was no other celebration. Besides a special meal while on line on the Marine Corps birthday (November 1951), there was a spectacular supporting arms display (time-on-target) on enemy positions. At Christmas, Cardinal Spellman celebrated a special mass, at which some Catholic Marines in G-3-1 were able to attend. When in reserve, I attended services when available. I was not able to attend any of the USO shows. I also had no R&R opportunities. Helicopter PatrolAn incident that still stands out in my mind involved a helicopter patrol where the helicopter failed to rendezvous with us and we had to walk all night in freezing weather to return to our unit. It took place during the winter of 1951--either late November or early December, I don't exactly remember. Use of helicopters in Korea appeared to evolve from their use to evacuate wounded. This undoubtedly saved many lives of those that would have otherwise died of wounds. Because choppers could land and take off from places other craft could not, their use to transport small troop units was a natural sequel. Their use for combat/combat support, i.e., armed platforms, came later, e.g., in Vietnam. In any case, moving a reinforced squad to a particular place on the ground enabled a patrol to operate in a day farther away than it could by walking. This assignment, like all others, came from Battalion. Whether my platoon assignment came from Battalion or from the Company CO, I never knew. However, the details of the times of departure and pick-up, routes to be covered, etc., were dictated by Battalion. The squad selected was the one recognized to be the most experienced in the platoon. Our squad leader was Harry Schubach, whose funeral at Arlington in the 1990s I attended. He was a career Marine and retired as a Master Sergeant. George O'Connor was a Fire Team Leader in Harry's squad. Both Harry and George had joined the G-3-1 Korea group. "Rebel" Harrison was a rifleman in the squad. Billy Gibson was a Fire Team Leader and PFC Morris (I think) was the radioman. I don't remember any other Marines' names in this particular squad. A long time ago, I lost my notebook and personal records, so many names and locations were lost to my memory. The pilot was only a face when we boarded the chopper. No names were exchanged. I don't remember whether he was a Marine or Army pilot. As best as I can recall there was a full squad, plus the platoon leader (me) and my radioman in the chopper. Because of the rotor noise, no element of surprise was possible with that generation of helicopter, nor was it intended to be. Our briefing told us that there were no known enemy forces in the area, but the mission was to determine that the assumption was true. The patrol mission was somewhat successful in that we didn't find any enemy. The "crow-fly" distance between the drop-off and pick-up was not a problem. However, there were moderate hills between the sites and the "up-and-down" distance added to the total distance to be traversed. That distance difference, coupled with newly fallen snow, increased the effort necessary to get to the designated pick-up point. The time between drop-off and pick-up was about eight hours--all in daylight. Our identifying signal to the chopper was to have been a green-smoke flare fired at a designated time from near the pick-up zone. The flare was fired, but the chopper did not remain in the area. It left us on our own to return to our headquarters. Although no enemy resistance was encountered to deter us, the snow encountered along the mountains traversed was a significant delaying condition. Walking was slippery. Men slipped and fell. Communication between the patrol and Battalion Headquarters was by a backpack type radio. My radioman fell, damaging the radio such that it could not be used to communicate our situation. The loss of the use of the radio hit the radioman hard because he felt that he had let the rest of the patrol down. In addition to the snow and ice, temperatures remained below freezing. The terrain features and their impacts on the mission have already been described. As night fell, the temperature dropped to near zero. There were streams to be forded during our return. Because going was slippery, some men fell into the water and wet clothing, coupled with the freezing temperatures, became a survival hazard. During the return, one of the riflemen ("Rebel") was exhausted and wet and cold. He wanted to stop and rest or be left behind, but I feared the effect it would have in the cold. "Rebel" kept pleading and I kept refusing. After many pleas, the squad leader said to "Rebel," "If you don't shut up, I'll shoot you myself." During the approach, there were rest opportunities that were taken because climbing was difficult work. After the men became wet and cold, the return hike did not afford opportunities to rest. Walking kept the body heat up. My major concern was the safety of my men. The initial slippery going was a concern that men might fall and be hurt. This concern was exacerbated when the chopper was not available to effect our return. The loss of radio communication became an additional concern, in that we could not inform Headquarters of our situation. Frustration was initially the fact that Operations had not read correctly the topography of the area we were expected to traverse, thereby causing us to accomplish a greater distance to get to the pickup zone. A greater frustration was the fact that the chopper didn't respond to the pickup and we had a much greater challenge to get back to our area. I don't remember the return distance, but we walked all night. It was early morning when we ran across the Army unit. Since the patrol was behind the combat line, the Army unit was a rear echelon one. I don't remember its organization or its function. Since the Army was tied into the Marine Division's left flank, I knew there was Army somewhere. When we reached the unit's area, we were able to contact Battalion Headquarters by telephone to inform Headquarters of our location and situation. The Army provided us some food and transportation back to the Battalion. I never participated in another chopper patrol. G-3-1 returned from reserve to the combat line on the Korean eastern front. When the Marine Division moved from the eastern front to a blocking position protecting Seoul on the western side of the peninsula in March of 1952, my time to be rotated to another assignment came up and I left George Company. Leaving George Company for me was a little emotional, because I had become attached to my platoon members. They were still going to be in a combat location and I wasn't. However, there was little time for "goodbyes" because George was also leaving for its new location. For me, the hardest thing about being in the line company had been that it was discouraging to not know how the war was progressing. Too little information was available about what was going on in other areas. Among my concerns, for example, was that while our Battalion/Regiment was online, especially at night, we could hear sounds of firing--incoming and/or outgoing--in the vicinity of other online units. There was too little information about the events, e.g., who/what initiated the firing; was there any visual detection of the enemy and, if so, how many; were any prisoners taken, if so, was any information acquired from them, etc. Such information could have been used as indicators of enemy activities and for considering proper/adequate responses. Being a young and green "leader" of combat veterans was also difficult. I felt I had to prove my capabilities to lead. The PLC training and the Basic School training only partly met a need. They gave some of the "what's" but not many of the "how's". One learned the latter by on-the-job training, thanks to those that had "been there done that." I consider a "hero" to be someone who, in the face of overwhelming adversity, kept his "cool" and rallied his men to perform and accomplish a mission. Although I was not in G-3-1 with them, Carl Sitter and "Speedy" Wilson, each of whom earlier earned a Medal of Honor, meet that criterion. CSGIn February 1952, it began to thaw. As mentioned, I rotated to Masan in the far south (where I stayed until I rotated home) before the 1st Marine Division moved west. For me and other officers, rotation was two-fold: rotation from a line unit to a staff or combat support unit, then rotation from that assignment to home. Battalion Headquarters had asked whether I had any choice for the second phase assignment. I had thought that Battalion Operations (S-3) would be interesting, but no vacancies existed, so I said, "Wherever there's a need." I was assigned to the Combat Service Group (CSG) near Masan at the southern tip of the Korean peninsula. In Masan, I saw the primitive housing conditions in which most of the natives, including the children, lived. There was no interior plumbing, many people in a small "house", etc. There were natives in the camp who provided laundry and hut cleaning services. I don't remember any prejudices demonstrated against them while I was there. Korea, what I saw of it, had a natural beauty. I felt sorry for the people whose homeland had been demolished by aggressors. I felt justified in helping them. CSG provided higher echelon equipment maintenance and support for the Division. I had never heard of CSG, much less knew anything about what it did. Although I had no training in supply functions, I was initially assigned as a supply officer, and then later as Company Executive Officer (XO). Duty there was far less demanding than in G-3-1. There were regular working hours, hot meals, showers, afternoon volleyball or softball--a paradise compared with a line unit. Going HomeMy rotation home from CGS was delayed a month for reasons not entirely clear to me. There was some scuttlebutt that because of the delay, I might be flown back to the USA. Never happened. My name appeared on a rotation draft roster, along with some other officers from CSG. We were told to pack our gear and be ready to take a train to Ascom City, the debarkation point near Inchon. I have no recollection of the train trip--how long or anything. However, I have some pictures of several of us at a transfer point of the journey. I don't remember any special procedures that we went through. There were medical/dental exams, but nothing else sticks in my mind. I left Korea aboard the same ship that brought me to Korea in September or October of 1952, the General Meigs. Other passengers that I knew included Lt. Roger Barnard (5th Marines) and "Champ" Fisher (a supply officer). Although I have some pictures of others, I do not know their names. At Ascom City, some Army troops had loaded aboard ship, too. They were headed for Japan. As might be expected, everyone--me, too--was glad to be going home. I was apprehensive about "homecoming" because my wife had told me a few months earlier that she wanted a divorce, having met someone while I was gone. The hardest thing about being in Korea for me above all else had been being away from family and the uncertainty of returning to them. Another uncertainty now awaited me in the States. The only duty I can remember on the return trip was inspection of the troop's quarters and of the messing facilities. I don't recall any cases of seasickness. There was a short stop in Yokosuka, Japan to drop off the Army troops and to pick up some others headed for the USA. We stayed aboard--no liberty again! The trip home required about a week, I think. There were movies at night, and most of us sunbathed during the day hours. We returned to San Diego, from which I had departed a year before. Having grown up in San Diego, the recognition of Point Loma and North Island was especially meaningful. I could see the cemetery where my father was buried and the high school where I had been student body president. Off-processing was by rotation draft unit organization, officers after their troops. My mother and my wife were waiting on the dock, along with a great many members of families of other men aboard. I spent the early hours at home trying to effect reconciliation with my wife. It didn't happen. I was not able to salvage my marriage, and a divorce was granted in early 1953. Post-KoreaI was assigned temporary duty at Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego, pending release from active duty. In addition to mess inspections, officer-of-the-day, etc., I was assigned to a security detail for a local "fair." I was eagerly awaiting release from active duty so I could return to graduate school at San Diego State, interrupted by call-up for Korea. I had obligated service remaining. I was not discharged, but merely released to an inactive Reserve status. My return to civilian life was not a problem because of my burning desire to complete my education. After I was released from Marine Corps active duty, I returned to San Diego State in September 1952 to finish the requirements for a General Secondary California Teaching Credential, which I received in February of 1953. My return to school after Korea was similar to the World War II vets returning to school after their war-time experiences. I, as they were, was anxious to get my education and get on with my life. Although college/university life was fun, I was serious about my studies and my work. Those were my priorities, as they continued to be throughout my professional career. While finishing the credential work, my major professor strongly encouraged me to pursue a PhD program and, through his assistance, I was accepted at UCLA for a Teaching Assistant position in the Chemistry Department beginning in March 1953. I taught a lab section of Freshman Chemistry and tried to make up for not having studied anything related to chemistry or mathematics in two years. Yes, I was rusty! During my first semester at UCLA, I lived in the Kappa Sigma fraternity house and played intramural sports (basketball, softball, volleyball--we won the intramural championship, going through the regular season undefeated!). I saw a part-time job announcement for a Radiation Safety Engineer at UCLA that paid more than my teaching assistantship. I applied and was accepted. Later, my boss accepted another position at UCLA and recommended me for his job, which I accepted. I worked full-time heading the Division of Radiation Safety, with oversight responsibilities for radiological projects at the Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, Riverside, and La Jolla campuses of the University of California while completing the course and research requirements for a PhD in Physical (Nuclear) Chemistry--awarded in August 1959. While at UCLA, I sang in the choir of the Westwood Methodist Church, where in 1955 I met another Betty, who was working at the RAND Corporation. When I was certain when I would be finishing my studies and research, we were married in 1958. She had a young daughter, Beverly, by a previous marriage, whom I adopted. We had two more children, Bruce (1959) and Betsy (1962). The office at UCLA was being reorganized at the time my research was completed, and I sought a more technically demanding position. I accepted a laboratory research position with the Atomics International (AI) Division of North American Aviation (NAA) that had a large research complex in the San Fernando Valley near Los Angeles. While there, I did research using radiochemical methods to characterize radiation effects on nuclear reactor fuel materials. Later I was appointed Supervisor of a 60-person analytical chemistry laboratory and was also responsible for developing a plutonium chemistry capability for AI and corporate NAA. In 1970, when the aerospace industry in California was going downhill, I was contacted to see if I was interested in being considered for the Directorship of the Atomic Energy Commission's New Brunswick Laboratory (NBL) in New Jersey. I interviewed and was accepted for the position, which I assumed in February 1971 until I retired from Federal Service in February 1995. The lab outgrew its environment in Jersey and was relocated in its entirety in 1977 to a location on the site of the Argonne National Laboratory, near Chicago, Illinois. I moved with it. Since my retirement, I've been consulting for the Department of Energy evaluating projects that have been tasked to assist Russian facilities in protecting and accounting for their nuclear materials. In addition to the consulting, I've continued my involvement with the G-3-1 Korea Association, having served as President and also as Secretary. The latter responsibility involves publishing a newsletter three or four times a year and maintaining the personnel records of the Association--much of which I've computerized. It is a labor of love. I've maintained an active participation in the Carson Valley Methodist Church where I sing in the choir, and I am a member of Carson Valley Kiwanis Club. The church and Kiwanis families are enriching factors of my retirement life. I enjoy bike riding (which I'm able to resume after a second hip replacement), working in the yard, reading, and watching sports on TV. Most importantly, however, my retirement allows me to spend time with Jodi's (my current wife) and my children, our grandchildren (12) and great grandchildren (3). Active Marine Corps ReserveWhile I was attending school on the GI Bill, I needed additional funding to support living in the Los Angeles area. Therefore, I looked into Active Marine Corps Reserve units. The infantry battalion (Santa Monica) had no vacancies. However, the artillery battalion (2nd 105mm Howitzer Battalion) told me that if I agreed to re-train in artillery, they would accept me as a Battery Officer. I did and they did in 1954. I remained in that unit with increasing levels of responsibility and promotions. I progressed from Battery Officer, through Battery Executive Officer (XO), Battery Commander, Assistant Battalion Operations Officer, Battalion Operations Officer, Battalion XO, and ultimately to Battalion CO--rising in rank from 1st Lieutenant to Lieutenant Colonel. The Battalion had been re-designated a number of times, lastly becoming 1st Battalion, 14th Marines (1/14), 4th Marine Division. The 4th Marine Division was the Reserve Division. Of all the Reserve artillery battalions, 1/14 was the only one whose batteries were co-located such that we could train as a battalion. This was of particular advantage at summer training time at Camp Pendleton or 29 Palms, California, where we didn't have to get acquainted before starting our summer training. Consequently, 1/14 received excellent performance ratings. During the Vietnam period, mobilization of 1/14 had been a distinct possibility. While I was the CO, I, along with my staff, presented mobilization readiness briefings for the MC Chief of Staff (General Chapman, later the Commandant) and again later for Gen. Lew Walt. We really expected to be mobilized, but gratefully it didn't happen. When I was selected for Colonel at age 40, I was promoted out of the Battalion in 1969. I continued to participate in Staff Group assignments until 1970, when I accepted a job with the Government on the east coast. The job involved a fair amount of travel, so Reserve affiliation was not immediately possible. When the job was reassigned to the Chicago area, I sought a Reserve assignment, answering a Staff Group vacancy announcement that went well both in my eyes and that of the interviewer. However, someone much junior to me, but having local "connections", was appointed to the position. I decided to tender my retirement letter. I was transferred to the Retired Reserve in October of 1978. Final ReflectionsMy return from Korea made me aware of the responsibilities that the United States had undertaken--a protector against the spread of communism. I gained a respect for the men and women in the armed forces in what they were training to be prepared to do. If the United States hadn't gone into Korea, I believe that more than just Korea would have succumbed to communism. MacArthur's mistake after Inchon, in my estimation, was not listening to or trusting intelligence reports that going to the Yalu would be read as a threat to China and result in its entrance into the war. Going north of the 38th, per se, was not his mistake. But the push northward was not done in an integrated manner such that it became possible to split the US forces and drive them south again. I've not gone back to Korea as some of my comrades have, nor do I have a desire to return. If I were to go back, I'm sure that I wouldn't be able to return to the ground where I spent most of my time. The rebirth of South Korea is a known fact. Seeing it is of no interest to me. As long as North Korea's forces remain a threat to the South Koreans, a response force is appropriate to the US's and the free world's interests. War is not pretty. When civilians are "used" by the enemy as a shield or a diversion, they are going to get hurt, just as they did in the Reservoir campaign. I don't know the facts of the Nogun-ri incidents, but I suspect that the reporters have not been in combat and have no idea of what decisions have to be made in a short time to react to a situation that, if you'd had more time to think, you might have done something different. Is the United States government doing an adequate job in its attempts to recover our Korean War missing in action? The answer lies in the hearts of the families affected. I know that Paul Dixon's nephew (a retired Army Lieutenant Colonel) is still trying to come to closure regarding the MIA status of his Uncle Paul, missing in action from Boulder City. The Korean War is "The Forgotten War" because people have forgotten why we were there and what sacrifices were made by many in the cause of defending freedom. I would hope that someone reading this someday would learn that a decision made by the President of the United States to stem the flow of communism was a success because there were men and women willing to sacrifice for that cause. I've told my kids that I wouldn't take anything for my experiences in Korea, that I wouldn't want to do it again, but most of all that I would hope they wouldn't have to go through it in their lives. Other details may have come out as anecdotal information. I'm making sure that the G-3-1 history that we've prepared is available to them if they're interested. Many of the G-3-1ers are looking for those that we served with. Of the about 1700 names that we know of from personnel data obtained from Headquarters Marine Corps, there are only about 400 whose whereabouts we know. I've been trying to find some of the officers that I served with, but to date have been unsuccessful in finding any of them. I've only attended G-3-1 reunions, none of the regiment or division, because I'm closer to those men than to those of the larger units. Because of the camaraderie, the pride, and the dedication to duty, "Once a Marine, always a Marine." AddendumMeet Your New PresidentSubmitted by Jim Byrne, G-3-1 Historian

|

|||||||||||||||

Photo Gallery(Click a picture for a larger view) |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||